Hetain Patel

Baa’s House I 2015

© Hetain Patel

In the past few years, a growing number of contemporary artists have been citing an unexpected influence: their grandmothers. Unexpected, because modern art, as we knew it, was all about the artist’s radical isolation in the studio, cut off from society and the family. To be modern has been to break with tradition and make something new. As the artist and critic Suzi Gablik wrote in Has Modernism Failed? (1984), the obsession with speed and technology that was the hallmark of the early 20th-century movement of futurism meant that: ‘whatever was inherited from the past was thought of as a tiresome impediment to be escaped from as soon as possible’.

Yet lately artists have become emboldened to acknowledge the ways in which the skills, traditions and stories inherited from their grandmothers have shaped them. The phenomenon is so pronounced that it has become a significant point of discussion about how we shape ‘the story of art’ in curatorial meetings at Tate Modern. (My colleague Nabila Abdel Nabi and I had even begun keeping tabs on artists who represent this tendency, by starting our own #grandmotherwatch.) Looking at recent exhibitions, from to carry (Sharjah Biennial 16, 2025, with its focus on the transmission of intergenerational knowledge) to My Oma (Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, 2024), it’s clear we are not the only ones who have noticed this marked turn to our past and elders. But why?

What was lost in the 20th-century idea of the lone modern artist, according to Gablik’s thinking, was transcendence. She didn’t necessarily mean solely spiritual or even religious transcendence, but a sense of one’s social self – of being part of a wider network of individuals rather than simply expressing one’s alienated, inner reality. Gablik wrote her book about modernism’s failure over 40 years ago. She disliked the movement’s ‘immunity from the responsibility of tradition’ and sought a new sense of ‘form, structure and authority... to sustain the spirit’. While her words resonate anew today, she couldn’t have predicted the exacerbation of social fragmentation caused by the internet, and now artificial intelligence.

Tanya Lukin Linklater

The Treaty is in the Body 2017. Production photo by Liz Lott

© Tanya Lukin Linklater. Courtesy of the artist and Catriona Jeffries

In the early 21st century, an emergent generation of artists seems to be fervently reviving these aspirations towards a spiritually, and ecologically, sustaining art practice. Born into an accelerated, hypermodern world of atomisation that was unimaginable in the 1980s, many artists today are reconnecting with their grandparents’ generation via the forms of making and knowledge they have gleaned from them. This isn’t a polite continuation, though. Invocation of the grandmother, and all she is associated with, can represent different kinds of radicalism, resistance and refutation. Artists draw on grandmotherly traditions from Indigenous, folk, activist, spiritual and craft-based perspectives – and her figure affords both rich inspiration and fierceness. Most importantly, these traditions speak to the interweaving of the political, utilitarian – even agricultural – and the cultural, rather than keeping art in its own separate sphere.

A case in point was the show, titled akâmi-, by Cree artist Duane Linklater at Camden Art Centre earlier this year, which featured a work from Tate’s collection. akâmi- is an Omaskêko Cree word for ‘across’, which has multiple meanings that disrupt Western notions of temporality, confronting past, present and future simultaneously to create space for Indigenous presence in every moment. Linklater has credited the show to fellow artists and his own grandmother, Ethel (Trapper) Linklater. In a similar vein, Tanya Lukin Linklater, Duane’s partner and collaborator, writes about sewing practices shared by aunts and grandmothers. These art forms manifest in her video work The Treaty is in the Body 2017, which shows young girls plaiting hair, writing and drawing about what they learn from knowledge holders, and developing these ideas through dance.

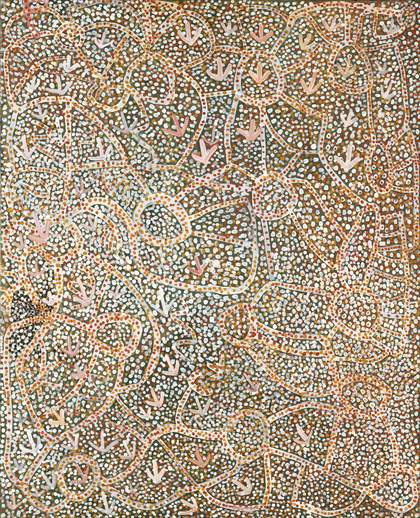

Similarly, a film within the current exhibition of works by Aboriginal artist Emily Kam Kngwarray at Tate Modern shows members of her Anmatyerr community in Australia’s Northern Territory discussing the role of the matriarch. They describe how they learnt their song and ceremony – powerful body-painting and singing practices owned collectively and passed down the female line. ‘The old women are holding their Country as they dance. The old women dance with that in mind’, says Anmatyerr artist Kathleen Petyarr. ‘They teach the younger women and give them the knowledge, to their granddaughters, so then all the grandmothers and the granddaughters continue the tradition.’ Emily Kam Kngwarray’s paintings might look to some like the abstract expressionist canvases produced by existentially fraught Americans in the 1950s – but look closer at the plant forms and cosmic patterns shaping her compositions, and you understand that her work has grown from a community-born practice rooted in long lines of traditional making, and a deep, ancestral relationship to fellow humans and the ecological territory for which they care.

Edgar Calel

Me Venden / Mani yi na besq ́opij IV 2024

Courtesy of Proyectos Ultravioleta, Guatemala City. Photo: Margo Porres

Notably, it is not only women artists on our #grandmotherwatch list. Edgar Calel, whose work is currently included in Tate Modern’s collection exhibition Gathering Ground, wrote in charcoal on the back of a recent series of clay-on-canvas paintings a phrase that translates as ‘Do not let go of me’, inspired by his grandmother’s words. Calel originally learnt from his grandmother the knowledge, cultural customs and crafts of the Maya-Kaqchikel of Guatemala, Indigenous knowledge that he now introduces to contemporary art in ways that challenge Western value systems based on individuality, money and ownership. He is comparable to Linklater in this regard, and also to the current Hyundai Commission artist, Máret Ánne Sara, who draws on her Sámi heritage and reindeer herding community to make her art. Calel’s work in Tate’s collection is not owned by Tate following a straight transaction; Tate is merely the work’s temporary ‘custodian’, with a set of reciprocal responsibilities.

This accumulation of parallel attitudes represents a profound political and aesthetic shift within art. In July, at an event for artists recognised during the selection process for the new future-facing Infinities Commission at Tate Modern, one awardee, American artist and curator Rashida Bumbray, spoke passionately about the significance of African American traditions of plaiting and quilting, passing messages and sustenance from grandmother to daughter to granddaughter since times of slavery. These apparently intimate, domestic activities represent forms of resistance that echo the political messages coded in textiles, such as in Palestinian embroideries or Chilean women’s arpilleras – hand-stitched, patchwork pictures. Likewise, Faustin Linyekula, an artist from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, has worked for many years on culture carried through matrilineal lines in his choreographic work My Body, My Archive. Yet, as Linyekula has asked in a recent dance work, in which traditional Congolese wooden sculptures are staged as ‘performers’: why have women’s contributions been erased from history’s long view? He is one of many artists to question the lack of visibility of practices traditionally associated with women, such as hand embroidery, which are fragile and are most often learnt via person-to-person transmission, as opposed to the more permanent products of, say, woodcarving or oil painting.

The idea of passing on living traditions echoes the storyline of Alice Walker’s 1973 short story ‘Everyday Use’, in which the dynamic between an African American mother and her two daughters hinges on their relationship with African family heirlooms. The story contrasts two views of art: one that prizes objects for their artistic value and that seeks to preserve them (as if within a museum), and another that cherishes a lived relationship with the object. Such profound questions are raised by curator Osei Bonsu in the Nigerian Modernism show, now at Tate Modern. Included in the exhibition are the works of mid-century artists such as Uche Okeke, who incorporated Igbo Uli traditions of pattern-making in his paintings. These practices of painting the house or body have been traditionally carried out by women, but it was only when they were transposed to oil paint on canvas that they became valued as art recognised in markets and museums. Kimberley Moulton, a curator at Tate who specialises in First Nations art practice, has spoken about the concept of rematriation, a term first used by Stó:lō author Lee Maracle in the manuscript for her 1988 book, I Am Woman. In contrast with repatriation, which focuses on the colonial looting of objects and their restitution, rematriation is concerned with a ‘return to the sacred Mother’ – using traditional and cultural Indigenous knowledge to care for the planet and honouring Indigenous matrilineal systems.

Uche Okeke

Ana Mmuo [Land of the Dead] 1961

© Uche Okeke, The Prof Uche Okeke Legacy Limited and Asele Institute Ltd/Gte. Photograph by Franko Khoury. National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution

Many of the contemporary artists I mention here invoke specifically Indigenous practices, but this is only part of the picture. The grandmother tendency has a feminist drive, but many male or non-binary artists are turning to the matrilineal. Albanian contemporary artist Anri Sala shares intimate recollections about his grandmother’s recipes in his video work Byrek 2000. Korakrit Arunanondchai, a visual artist of Thai origin, also invokes his grandmother within his 2017 techno-digital vision with history in a room filled with people with funny names 4. Even the emblematic artist of late capitalism, Jeff Koons, speaking in an interview some years ago, cited his grandmother’s love for the kitsch ornaments she kept on her mantelpiece and the permission he felt this gave him to embrace an alternative form of aesthetic appreciation – one that permitted the pleasure and emotion expressly denied by the clean lines of modernism.

The rise of the grandmother as influence is not a sentimental trend; it’s a significant pivot, not only away from patriarchy but also beyond women-only feminism. These are elements that have been explored in depth in our recent Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational symposium, Ancestral Knowledges: My Grandmother is My School, curated by Nabila Abdel Nabi, Kimberley Moulton, Marleen Boschen and others. Contrary to the view posited by a feminist art historical panel discussion I attended a couple of years ago titled (outrageously, in my view) Will Women Ever Catch Up?, this is a story of art that resets the starting points, one in which women no longer race to get somewhere, but are instead situated, with long-term significance, at its centre.

A quarter way through the 21st century, the idea of an art-historical canon is becoming increasingly contested, and the authority of museums is under greater scrutiny than ever before, especially for those tied to governmental power. What does this grandmother tendency mean for the narrative that we tell in the modern art museum? It changes things. Artists are openly demonstrating that they retrieve forms that have been passed on to them, rather than inventing work ‘from scratch’ as the American artist Barnett Newman claimed of his abstract paintings in the 1960s. Emerging from the late contemporary phase of art is, perhaps, a new resistance to time’s relentless drive forwards. Instead, we might see ourselves as being in a new state built on a recursive looping back – a dynamic present, with fresh hopes, and memories that are, in turn, attached to responsibilities. ‘What do you carry that also carries you?’ was the powerful question posed by Okwui Okpokwasili and Peter Born in their improvisational work inspired by Igbo women activists in the early 20th century, Sitting on a Man’s Head 2019.

Anri Sala’s film Byrek 2000 documents the preparation of the traditional Albanian dish and is projected onto a second projection of the artist’s grandmother’s handwritten recipe

© Anri Sala. Courtesy of the artist and Esther Schipper

South African artist Lebohang Kganye put it beautifully: ‘I remember seeing a set of drawings by an artist who recorded all the plants in her mother’s or grandmother’s garden, and spoke to me from a different place than my learnt understanding of contemporary art. It was like putting a stone in the stream’. This switch of perspective reroutes the story of art. And yet, lest it sound too gentle, these artists know they are invoking a powerful alternative. The grandmother is not only someone to learn from, she is also one of the few figures of strong female authority in the collective imagination. As British artist Hetain Patel, who made a choreographic work about his grandmother, observed, she is a ‘well of knowledge, an alternative to industrial modernity’. The grandmother is an institution in herself. Moroccan artist M’barek Bouhchichi – after whose words our November symposium was titled – encapsulated this with his description of his grandmother as simply: ‘my school’.

Gathering Ground, until 4 January 2026

Emily Kam Kngwarray, until 11 January 2026

Hyundai Commission: Máret Ánne Sara: Goavve-Geabbil, until 6 April 2026

Nigerian Modernism, until 10 May 2026

Catherine Wood is Chief Curator and Director of Curatorial, Tate Modern.

Gathering Ground is supported by Mala Gaonkar and Tate Patrons. With additional support from PPL and Tate Members. Emily Kam Kngwarray is presented in The Eyal Ofer Galleries. In partnership with the National Gallery of Australia and Wesfarmers Arts. Further lead support from Fondation Opale. With additional support from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Also supported by the Emily Kam Kngwarray Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons, Tate Americas Foundation, National Gallery of Australia Foundation and Tate Members. Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor. Hyundai Commission: Máret Ánne Sara: Goavve-Geabbil is in partnership with Hyundai Motor. Supported by the Máret Ánne Sara Supporters with additional support from the Máret Ánne Sara Supporters Circle and Tate Americas Foundation. Nigerian Modernism is in partnership with Access Holdings and Coronation Group. Supported by Ford Foundation, The A. G. Leventis Foundation, and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. With additional support from the Nigerian Modernism Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Americas Foundation.