WOLF JAHN Are there aspects about you, before you met, that are still important in your present life?

GEORGE We’re both very much country people, with Christian backgrounds – Gilbert Catholic, and me Protestant.

GILBERT I was very Catholic. I went to church every Sunday until I was nineteen or so. I never committed a mortal sin.

GEORGE Plenty of venial ones, but no mortal ones.

GILBERT My family was pretty much a peasant family, up in the mountains and totally isolated. I think that’s very important. When you’re isolated from life in the city, you’re different. I’ve never lost that.

WOLF JAHN And what made you interested in art?

GEORGE I was conscious that there was nothing around me that did interest me, but art seemed very attractive. Then I discovered van Gogh. It was very exciting reading his letters and seeing that you could become an artist out of any background.

GILBERT I was already interested in art when I was six or seven years old. I did drawings and wooden and marble sculptures – mostly religious things: cribs, Christs, Madonnas. My ideal of an artist was Michelangelo, the only image of a sculptor that was really famous. I was fourteen when I went to art school in Wolkenstein in the Italian Dolomites – against my father’s wishes.

WOLF JAHN Gilbert, what was it like coming to London?

GILBERT When I arrived at St Martin’s in 1967, I found this crazy art school where you could do what you liked. What I remember about London was the multicoloured skies – lilac, pink and all those crazy colours. Then I saw the work of the Pre-Raphaelites, whose colours were so different from anything I’d ever seen before. So I started making strange resin objects full of those crazy colours.

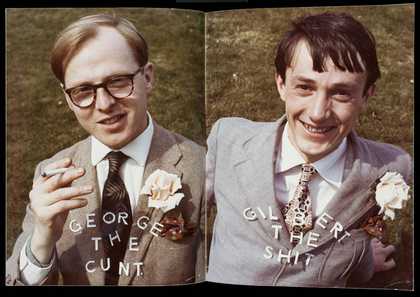

George as a mouse in an anti-rationing campaign late 1940s

© Gilbert & George

GEORGE We’re very much aware that the world we live in is totally different from the world we were brought up in. For instance, I never visited the capital city of Britain until I was 21. I’d never left my home county until I was probably twenty.

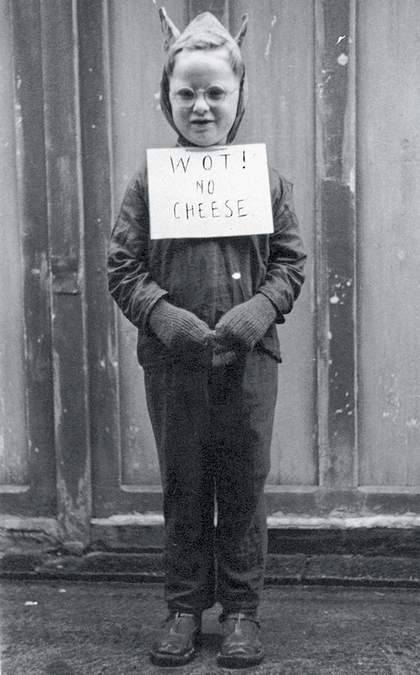

Gilbert in San Martino, Badia, Dolomites, Italy early 1950s

© Gilbert & George

WOLF JAHN George, when did you move to London?

GEORGE Two years earlier. I wanted to escape from the poverty of the time. At home, everything was very run down. There was no lavatory in the house, no hot water, no heating. There was never any money; nobody had a nice piece of furniture, or a radio that worked. I will always remember, when I first went to school, there was a horrible smell in the classrooms. It was the boys shitting in their trousers. And that was because it was the first time the poor boys had ever had a proper meal. They weren’t used to school dinners, such as a big meal of stew and apple pie and custard, and they didn’t know how to leave the classroom. That was the kind of immediate post-war poverty that I disliked so intensely.

WOLF JAHN How would you judge your childhood and youth?

GILBERT I had quite a nice childhood. But when I went to my first art school I felt I was the only person there from a different village, a different culture. So I already felt isolated. That was the beginning of feeling different. When I came to England it was the same – always the outsider. I think this was probably very good for me. George’s mother was one of the first women in that part of England to get a divorce. She had these two boys to bring up, and she wanted to make their lives different, every moment of the time.

GEORGE And better. We agreed with that. My mother sent me and my brother to elocution classes. My mother insisted that I shouldn’t have National Health spectacles. She worked like a dog to get those little gold-framed ones. We were never allowed to play outside with the other children. We were always separate in some way.

WOLF JAHN You met at St Martin’s in 1967. Did it take a long time for you to become friends?

GEORGE We were friends immediately. We used to go for dinner, explore the East End, Hampstead, everywhere, every afternoon.

Gilbert & George performing Singing Sculpture, Cable Street, London, 1969

© Gilbert & George

GILBERT It’s very simple. George was the only one who accepted my pidgin English. We made our own objects and showed them together, and then we did one object together – a head.

GEORGE You could say that it was a collaboration. We’ve never collaborated in that way since.

WOLF JAHN And then you started the series called Living Sculptures?

GILBERT In a way, that happened by mistake, because at the end of the year we posed with our sculptures, but we realised we didn’t need them. That was when we realised that we didn’t believe in objects.

GEORGE In our little studio in Wilkes Street in Spitalfields, we played that old record Underneath the Arches. We moved to the music, and thought it would be a very good sculpture to present. That, in a way, was the first real G&G piece.

WOLF JAHN You are talking about the Singing Sculpture, which you presented, off and on, for more than four years. Was it always the same?

GEORGE We soon discovered that wherever we did the Singing Sculpture it worked every time – people were glued to it. There was one small boy who wanted to travel with it forever, and wind up the gramophone for us; there was one lady who cried because it had something to do with a memory of her father. I think that’s the seed of what we have in our pictures today.

GILBERT And it even started to speak to us. Unhappy, lonely, alone. It became a living, walking sculpture that spoke to everybody.

GEORGE The important feeling we had was that we wanted to do something attractive and emotional. We didn’t want to do this grubby, fake-serious stuff.

GILBERT I remember we were very against the Arts Lab, where they did happenings, because to us happenings were disgusting. They were just rolling around with toilet paper, wires, beds falling down, rubber.

GEORGE We were happy to leave the world of St Martin’s behind. That’s why we liked the idea of the Postal Sculptures, which we mailed all over the world.

GILBERT That was a form we liked, in that we could send very personal messages. We told them how we felt. It had to be from us, handmade. They were an incredible success. We did them for about six years, concurrently with the Singing Sculpture.

WOLF JAHN Once the Singing Sculpture was defined as a form, wasn’t it risky for you to continue with it, to keep on doing it without change or evolution?

GILBERT The Singing Sculpture was very limited. So, in 1972, when we started drinking we decided to do decadent sculptures – pictures, in fact. But we were still the objects. We realised that we had become the Singing Sculpture, and it didn’t matter whether we were doing it in a gallery or not. Our existence became the artwork.

WOLF JAHN Was it a problem for you when the initial reaction was to accuse you of being ironic?

GEORGE We always tried to fight that. I think even to this day there are still people who would say our pictures are ironic. We don’t accept that.

WOLF JAHN Maybe it’s because of some of your early texts, such as To Be With Art Is All We Ask. That could be interpreted as ironic.

GEORGE We went into that completely honestly. When people think we’re ironic, it’s because they can’t believe that we ever actually meant to make, let’s say, a picture such as Shitty World. So they think it must be ironic. But, in fact, it’s exactly what we mean.

WOLF JAHN What is striking is that, once you found the final form of the Singing Sculpture, your art became extremely destructive.

GEORGE We wanted to explore our way out of the Singing Sculpture. It was like a drunken safari to explore new territory. We know drunkenness is a time-honoured subject for artists and writers, but the way we did it was new.

GILBERT When we did the Drinking Sculptures, we felt destructive. The happy days had been destroyed by the difficulty of life and art. We meant it. They were total life, but everybody in the art world thought they were meant to be funny.

GEORGE We could see that all the other artists were drinking, but during the day they painted a nice grey square with a yellow line down the side. We thought that was completely fake. Why shouldn’t all of life come into your art? The artists drink, but they do sober pictures. So we did drinking sculptures, true to life.

WOLF JAHN Have you always been destructive?

GILBERT I think so. We have been through phases when we were happier, maybe because bigger shows were going on. Personally, I don’t believe that there have been times when we’ve been less destructive. Not consciously.

GEORGE I think all honest artworks, or creative things, are destructive, in that they damage the creator in some way. We gradually realised that there is a price to pay. You fuck yourself up in some way by doing pictures such as Shitty Naked Human World. We become a little bit damaged, sexually or psychologically or emotionally. Very often the viewer doesn’t realise that. He says: “You must have enjoyed making that. ” In fact, it’s quite dangerous.

WOLF JAHN It sounds a bit like a suicide mission.

GEORGE It’s an emotional, psychological exercise, a journey you’re making, hand in hand with the viewers, because they are looking at the pictures. It’s very simple. If you want to explore South America, your boots are going to get damaged, you’re sweating, your face is cut, you might get shot at, you might shit yourself. You come back as a changed person, because you’re affected by it. Hopefully,you achieve something by making that journey. But there is a personal cost.

GILBERT Some parts of our work look more destructive, such as Dead Boards, Red Morning, Mental, Bloody Life, but in one way they are all the same: they are all based on unhappiness. And this has never changed. There is never a happy period of Gilbert & George.

WOLF JAHN You once named an exhibition It Takes a Boy to Understand a Boy’s Point of View. Was that about seeing the world in a new and simple way?

GEORGE I think we wanted to renew ourselves. We always wanted to be baby artists. Just as making the Naked Shit Pictures made us into different people. Someone said it looked as if we were being reborn in those pictures.

GILBERT And we don’t like to be polluted by art, by art-art. We don’t want to look at other art, we don’t want to read books about art, we don’t like to look back in history. But a lot of art historians would be horrified. They say you should become more and more learned, more and more sophisticated, more and more refined. We just want this clear simple vision of ourselves.

WOLF JAHN Very early in your career you were proclaiming “Art for All”. What did it mean in the beginning, and what does it mean now?

GEORGE Initially, we wanted to create art which avoided the language of sculpture. Because we were taught at St Martin’s that sculpture was like dentistry. If you hear two dentists talking, you don’t know what they are talking about - you don’t know all the terminology. We think that we should be able to make a sculpture that can address every man, woman or child, whether in Africa, New Zealand, or anywhere.

WOLF JAHN Is that why you called one group of works New Democratic Pictures?

GEORGE Absolutely.

GILBERT A democratic language that speaks to anybody.

WOLF JAHN Aren’t the other pictures democratic?

GEORGE I think they were more democratic because they were the first ones in which we were naked.

GILBERT We were trying to tell the viewer that in our art everyone can be involved. We have to say that again and again. So we sometimes find new words to explain the whole idea of “Art for All”.

WOLF JAHN But there are other artists who have said they’re democratic, such as Andy Warhol, because he showed popular subjects that everyone knew.

GILBERT He was interested in people.

GEORGE In his own way. It’s not a way we’d like for ourselves. We wouldn’t like to use famous people, famous drinks, famous cigarettes in our work. That’s a different kind of democratic art, entirely.

WOLF JAHN In the beginning there was just you in the pictures. It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that you started to integrate other people. Why?

GEORGE Strangely, the first time we really used other people in our pictures was after having photographed them with a long lens from the window. It was some Asians and some tramps. It never occurred to us that we could actually have somebody to model for us. It took a long time before we asked someone on the street, and even longer before we asked our friend Andrew, who modelled for us in an artistic way, indoors. Then we started to organise to have strangers to come and model for us.

WOLF JAHN If you want to invent the human person, in what direction does it go?

GEORGE We just want to get away from the classification of the person. When the news-papers talked about the miners, there was never one miner with a certain face. We want to think of new ways in which people can get up in the morning and be completely different, rather than just feel like a citizen, an Englishman, or a member of the EU.

GILBERT Many people say that the young people in our pictures are all East-End boot boys, thugs or hooligans. We don’t believe that. We are showing for the first time that a person like that is a total and fantastic human being.

GEORGE And beautiful as well. A fine person, finely dressed and proud. For instance, in Medals,we made them like emperors on coins.

WOLF JAHN At the beginning of your career you used colour in some of your works, but not in all In the Singing Sculpture the face and hands were multicoloured, but your first pictures were all grey.

GILBERT We wanted colour at the beginning. That’s why we wore the make-up. When we did the Charcoal On Paper Sculptures, we stained the paper, but we couldn’t make them colourful, because the idea was to make a drawing that looked like an antique.

GEORGE We discovered black-and-white first, because it’s neutral. It came out of the Drinking Sculptures, in fact.

GILBERT Because of drunkenness. Dark shadows, swastikas, malice, unhappiness, the dark side of life. Doom in many ways.

GEORGE And then we added red to make it aggressive and bleeding. Anger, a lot of blood. In fact, we had flame-red tape framing the corner panels of the Dark Shadow pieces, before we had red in any of the pieces. Then we started actually introducing it into the pictures.

GILBERT We used our own blood. We really wanted to express blackness and bleeding, trying to express real blood, suffering.

GEORGE Because the doom has no aggression in it. Doom is just doom. Once you have red as well, then it becomes very lively, very aggressive.

GILBERT And then we used grey to do Dead Boards. We were trying to do something that was absolutely hopeless, dead, grey, lost. Grey is misery, lonely, sad. And when we did the Mental pieces with red again and flowers, at that time we were so desperate that we thought we were mad. But we wanted to create a madness that was puritanical. We were nearly beating ourselves to death - and then we were on the other side. And then we did the Dirty Words. We arranged strong black-and-white images to create aggressive power, with red, and those again were based on the frustrations of life. We included the out-side world -policemen, tramps. We also realised the frustrations that people expressed when they wrote on toilets or on walls. To us, those were so real, so important, by comparison with all the words in the newspapers.

WOLF JAHN What colouring material do you use?

GILBERT Mainly photographic liquid colours. Our colouring is close to the flat colour of Japanese print-making or Chinese painting.

GEORGE In our pictures, every colour has white behind it, with white paper shinning through.

GILBERT That’s why sometimes it becomes more real than a painting. Painting doesn’t usually have white behind it. But the Pre-Raphaelites put a white ground under it to give it that incredible brilliance. Or the medieval artists – they used to paint on gold, on silver, to light up the colour. Their reds became very powerful, because they were painted on gold.

GEORGE That’s good, because we don’t want realism anyway. The streets are always miserable. If you ask someone what the colours of the doors are in this or that street, nobody can remember. It’s much easier to remember one of our pictures, because it’s artificial. Reality is pretty invisible. It’s like normal-coloured movies, very forgettable, only one or two scenes that you remember.

WOLF JAHN The Dirty Words 1977 are the first of your pictures in which you use a wide variety of different urban images. One thing you find is a lot of soldiers, even a battleship. What was your interest in the militaristic signs?

GILBERT We showed the aggression of life. Hence the soldiers. Those pieces are very violent, in some ways.

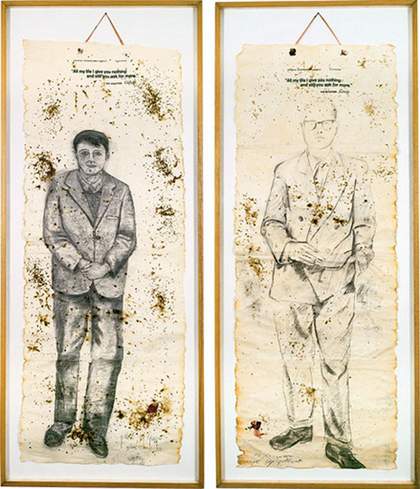

Gilbert & George

All my life I give you nothing and still you ask for more 1970

Charcoal on paper

Each panel 193 x 75 cm

© Gilbert & George

GEORGE We wanted to accept that aspect of Western life in our pictures, rather than being anti-Bomb, or anti-army, or anti-police. But we also showed the opposite: the sad soldiers on war memorials. Those are not so aggressive.

WOLF JAHN In the 1980 pictures there are a lot of titles that refer to your surroundings, such as Aldgate, Bunhill Knight, Fournier Street. You have never done this since.

GEORGE We just wanted to use those because they were handy. It’s sort of modern townscape, you might say, the human townscape. The Western world is made up of those streets. You always have the sky, the ground and the buildings. They’re taken in such a way that they could be anywhere.

WOLF JAHN You also used a lot of national titles, Viking, Jap, Germanier, Britisher, England. And then you had a picture called NF. It was often mentioned by critics who assumed that you had some political involvement with the National Front.

GEORGE We say that’s the most poignant, the most accurate townscape produced by any artist in London at the time. There were hundreds of landscapes produced in Britain in that year, and we think ours is the best.

GILBERT It’s a townscape like Aldgate, but a political townscape, and it had an amazing power. still has.

WOLF JAHN But you have often said that your art is not political.

GEORGE That’s a townscape that happens to be political. It’s a townscape first, a very modern one.

GILBERT NF was a powerful sign at the time, a powerful sign that was part of the townscape. Can you imagine us doing a sign called Labour? What does it mean, nothing. Or Conservative?

WOLF JAHN You have a collection of religious and theosophical books. What is your interest in them?

GILBERT To see it written down, sometimes. We’re searching for what we believe in.

GEORGE To reinforce our own feelings. Whatever you really think might be crazy, exciting, possible, always turns out to be true. Like the book on colour theory, in which the meanings of colours corresponded exactly to what we thought. It’s reinforcing.

WOLF JAHN So you don’t read books because you want to know, to get information?

GILBERT No, we already know, but sometimes we need help, we need support. Sometimes we find a saying by Oscar Wilde, and we feel, yes, that is right. When we read J-K Huysmans’s Against the Grain, we thought, yes, a lot of that stuff is like us.

GEORGE We read sexual history books, also theosophical and Gnostic books. And we very much like reading biographies. We have read biographies of some artists, such as Samuel Palmer. We don’t read art books.

WOLF JAHN You have other collections besides books, such as ceramics and furniture by Christopher Dresser, the sexual history collections, nineteenth-century design manuals, the glass collection, the Brannam Art Pottery collection, the Edmund Elton vases, your Tantric and Indian art collection. Most are from the nineteenth century. Do you have a special interest in that period?

GILBERT It was close enough to us. And it was a totally neglected period.

GEORGE It was the beginning of modernity. Christopher Dresser was the first real designer in the modern sense. Brannam was the most successful art pottery in the world for twenty years.

WOLF JAHN Do you have a collection of paintings?

GEORGE Very few. We did buy two huge Jain paintings, because we liked the idea of Cosmic Man. In some way,that was very close to our own feeling. We have some contemporary art. We bought something from everyone we were socially involved with – Alan Charlton, David Tremlett, Sol LeWitt, Hanne Darboven, Gerhard Richter and Barry Flanagan. Then we commissioned a collection of portraits of ourselves – two from Duncan Grant, one from Warhol and several from Gerhard Richter.

WOLF JAHN What about your collection of pin-up magazines?

GEORGE We still think that’s the most neglected field, and the most difficult material to come across. Our collection starts from the Second World War and goes until the present. It’s the most frowned upon by governments and by society as a whole. Legislation is still involved in deciding what you can and cannot publish.

WOLF JAHN I think your film The World of Gilbert & George has a lot to do with emotions and with possible ways of seeing the world. So let me ask you some of the questions you asked some of the young people in the film. What is the definition of happiness?

GEORGE Unhappiness, we used to say. But we wouldn’t say that now. Now that we’re on the way to our new pictures, I’d say that I’m sure we will be happy then.

WOLF JAHN What was the most interesting thing that ever happened to you?

GILBERT Meeting each other.

WOLF JAHN What was the worst thing you ever did?

GEORGE Wouldn’t like to tell you.

WOLF JAHN What makes life worth living for you?

GILBERT Being able to create new pictures, get them out into the world, and get a response.

WOLF JAHN What makes life unliveable for you?

GEORGE Same as everybody else, misery probably. There’s a point in misery that is very frightening, because you can see that if it ever became worse, it would be a bloody disaster. I’ve seen that. It’s all right to be a miserable artist, but to be a miserable person is too dangerous.