Towards the end of my studio visit, Christopher Wool and I browsed through his many publications, comparing reproductions of his work in their different contexts. Looking at books of his work is as revealing as talking to him about his art and the technical details of making it.

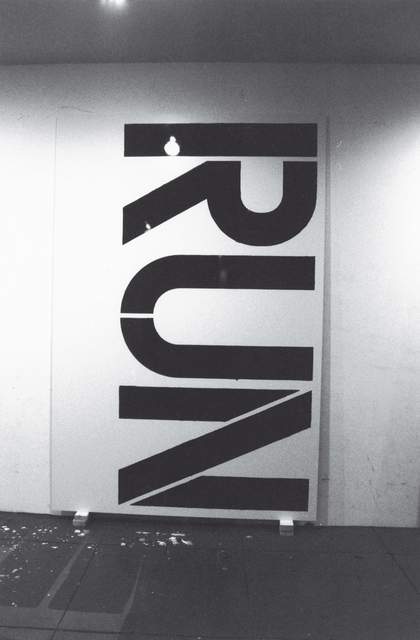

Wool first became known in the 1980s for paintings composed of short phrases or words stencilled in large blocky letters, often abstracted by omitting vowels. In a constant search for tools to replace the paintbrush, he later added to his repertoire tapestry rollers with repeating motifs, silk-screens, the obliterating gesture of a simple paint-roller and the spray can. And he has appropriated from his growing array of motifs, sometimes turning them into silk-screened versions of themselves, always renegotiating. The work keeps moving between opposites, eluding as it seduces.

Christopher Wool

Untitled 1990

Enamel on aluminum

274.32 x 182.8 cm (one of five panels),

as photographed by the artist in his studio, New York

© Christopher Wool

How to reproduce paintings that are dealing with the process of reproduction as much as the history of painting? It’s almost impossible to do it right. Instead, Wool does it in different ways, from self-published editions to handsome books with high production budgets. At his two-storey studio in Manhattan’s East Village, he pulled out some of these publications from a glass-fronted bookcase. We flipped through a book of Polaroids depicting paintings in process, as well as an oversized cardboard folio, produced by one of his galleries, containing unbound sheets of heavy paper, masterfully printed with paintings. Another book featured Xeroxed photographs from a year spent in Europe as a DAAD fellow, printed on generic office paper, while a 1991 artist’s book of colour Xeroxes, Cats in Bag Bags in River, is accompanied by a pamphlet consisting solely of a text by Glenn O’Brien. The precision with which each of these is conceived comes from Wool, who plays off the book as a specific form or genre as few other artists do. He engages with the convention and history of publications, from the cheapest to the most rare and refined, each time thinking through the printed reproduction anew. The meticulous care of his choices becomes clear as he explains that he has for years worked with the same German graphic designer. The longer we look through these publications, the more they suggest his process of painting.

Wool has decided against so many of painting’s possibilities: extensive colour, representational reference, a range of motifs, the sensuality of the brush and the variety of canvas size. He has said: “I became more interested in ‘how to paint it’ than ‘what to paint’.” The statement points to where he stands in his engagement with the history of images and the position of painting. For more than 25 years he has related to the changing state of reproduction: to the processes of picture making in all cultural realms, as well as to art’s recent and more distant histories. He is committed to the high stakes game in which image making finds itself after Abstract Expressionism, after Pop Art and after the Pictures Generation (e.g. Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman), thanks to the work of clear influences such as Pollock and Warhol, but also to an artist such as Dieter Roth, and even Bruce Nauman’s language-based prints. Wool’s attitude towards the role of images in our culture today, one which he shares with contemporaries such as Prince, Albert Oehlen, Cady Noland and Martin Kippenberger, has become increasingly important to a younger generation of image makers, including New York artists Wade Guyton, Josh Smith and Kelley Walker.

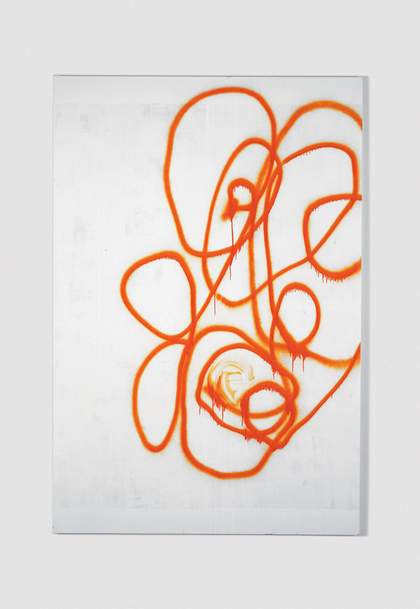

His restless adoption of tools allows him to keep pushing the restricted frame in which his art takes place. Some ten years ago, working first on large sheets of paper and then on aluminium panels, he began making pictures using a spray can, a device associated mostly with vandalism. The initial gesture was simply a single, long, tangled line, with highly liquefied, oversaturated paint dripping from the spray marks. Over this, wash-like strokes are made with some kind of paint thinner, looking at once like marks and erasures. This quality of erasing and covering, staining and removing, is reminiscent of a blackboard in negative. It’s the first time in Wool’s practice that we see something that approaches the direct mark-making hand of the artist, and the work has that spinning, undetermined energy that comes from stepping into unknown terrain. Though when I say direct, this method - the closest that he has come to the gestural line – is made with a tool that never actually touches the surface.

Some have proposed that Wool’s abstraction appears gestural and eminently pictorial while actually demolishing Abstract Expressionism’s idea of pictorial expressiveness. One should note that the drippings of Pollock, while traditionally seen as uncontrolled, were in fact highly disciplined. When embarking on a drip painting, for example, Pollock often carefully reproduced the contours of his earlier compositions from the mid-1940s: a way to get things started before moving into a less controlled and rhythmic or musical motion. Hans Namuth’s well known photographs of the artist at work document how he struck a balance between coincidence and control in achieving this pictorial expressiveness.

Pollock is an artist of some significance to Wool, who also might use a familiar form in order to enter a less stable space. Around 2000 he began to combine many of his previous approaches in a series of large-format paintings. At first, he simply used a photograph of a finished painting to make a new silk-screen version. The digital image is then divided into quarters for silk-screening, in part because the enlarged end product is too big for a single screen. In the printed picture, the edges between the four component panels remain delicately visible, indicating the painting’s method of production without preventing overall resolution. Wool then started to add details appropriated from his existing work: copied, repeated and superimposed. Before he makes silk-screens of these photographs depicting brushstrokes and stains, overlaid with wiped or sprayed marks, he digitally manipulates the appropriated elements by cropping them and altering their depth, contrast, or registration. He began to draw on these photographs in Photoshop, adding digitally generated lines, which may be distinguished from actual spray-painted lines only through their lack of drips.

Christopher Wool

Untitled 2000

Enamel on linen

274.3 x 182.8 cm

© Courtesy the artist/Luhring Augustine Gallery, New York

What is the “true” or “best” reproduction of such paintings, which appear as the arbitrary outcome of carefully achieved randomness? Rather than pursuing the realistic or correct colour, contrast and depth in reproductions of his work,Wool often prefers photographs that grasp the atmosphere, the idea of the painting, how it felt when it was hanging in a gallery, a museum, or the home of a collector. How did it feel when it was leaning against the studio wall? For work to stay alive in photographs or books, it’s important to catch the particular characteristics of the space in which it is seen, as well as note how the picture was taken. Wool likes to take these pictures himself, snapshots that include and even highlight the floor, wall, or windows, and occasionally structural columns that partially block one’s view of the artwork. This last is a gesture of obscuring, covering and correcting that also appears in the paintings, as in the wide bands of paint he rolls over a work’s surface: erasing as a form of image production.

The same control Wool exercises in taking these pictures, which initially appear random, is brought to decisions about how to reproduce them for publication. Traditionally, one might colour-correct images by whitening the walls, increasing the picture’s darks and keeping the mid-tones, but he seems to prefer that traces of uneven light remain. He keeps elements that are possibly undermining or destabilising for the work: reflections on the glass of the frame, dim corners, stray electrical outlets, tables, chairs. All of this adds up to a feeling of what it was like to observe the paintings at a particular moment. Wool’s careful and guarded decisions about the representation of his work are intimately linked to the challenges to reproduction implicit in the paintings themselves, which is to say that they are intimately linked to the position of images - that is, to the way images are produced and seen today.