9 rooms in In the Studio

This room brings together works by two leading artists from the Caribbean. Both explore the legacy of female mythological figures

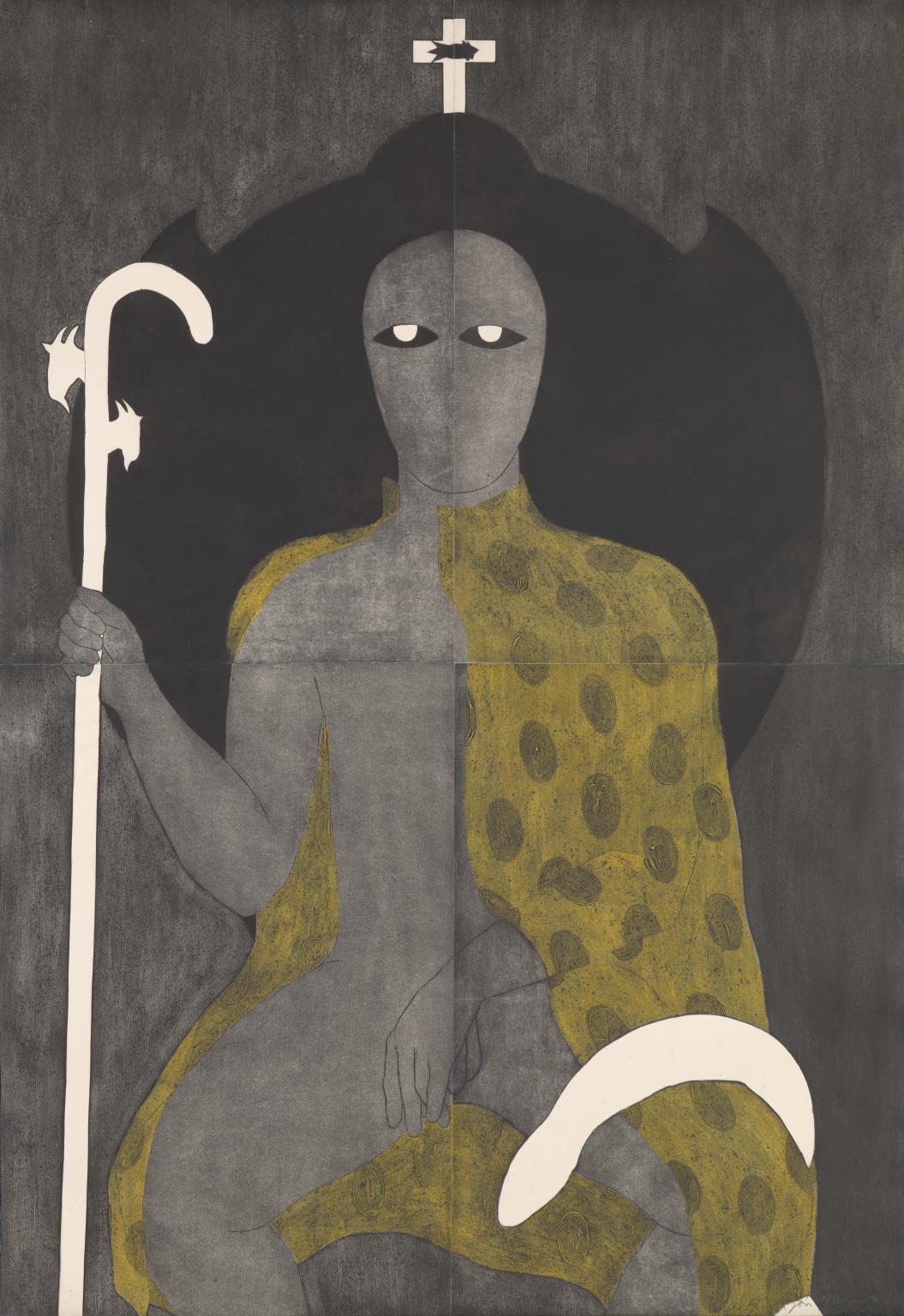

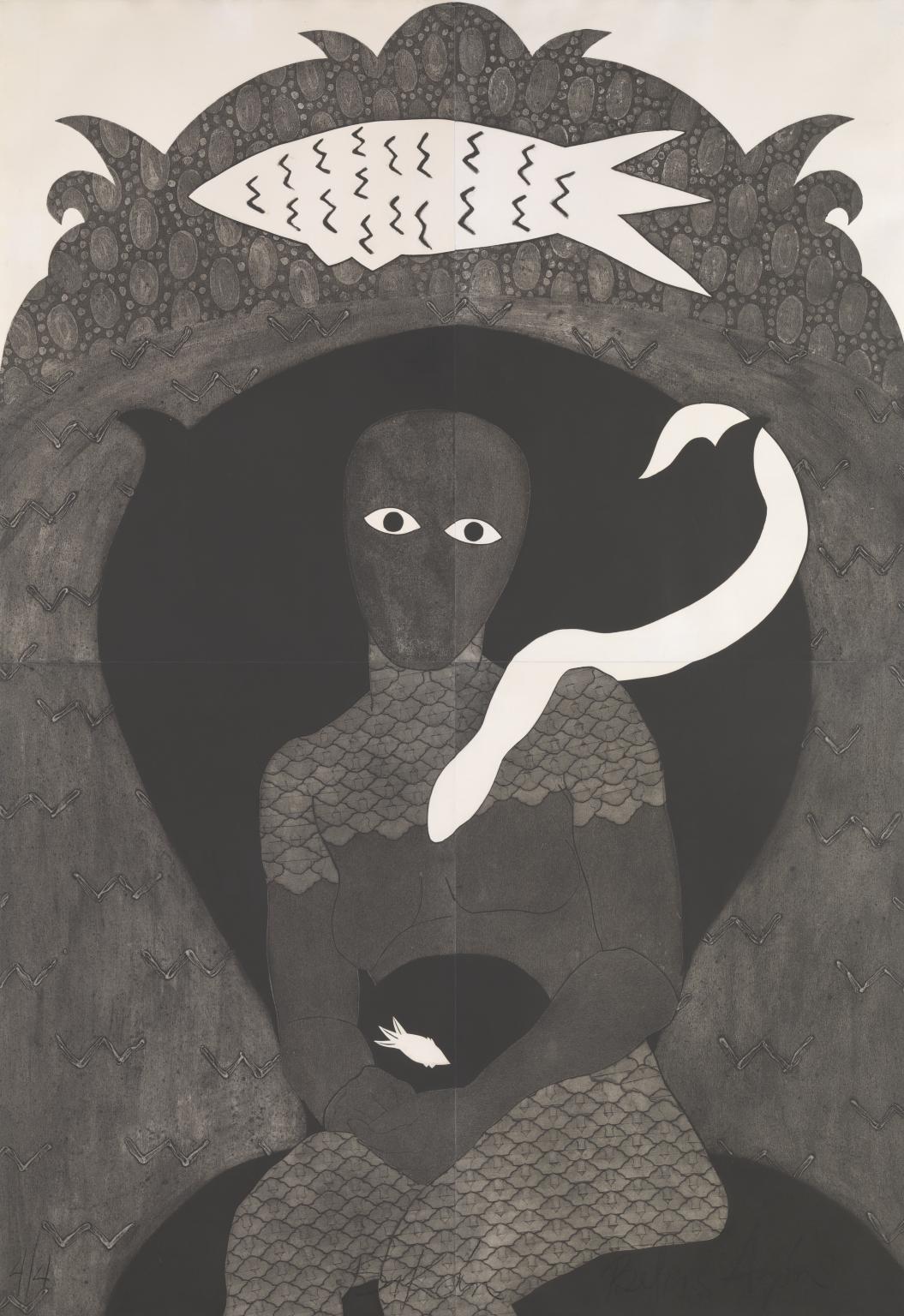

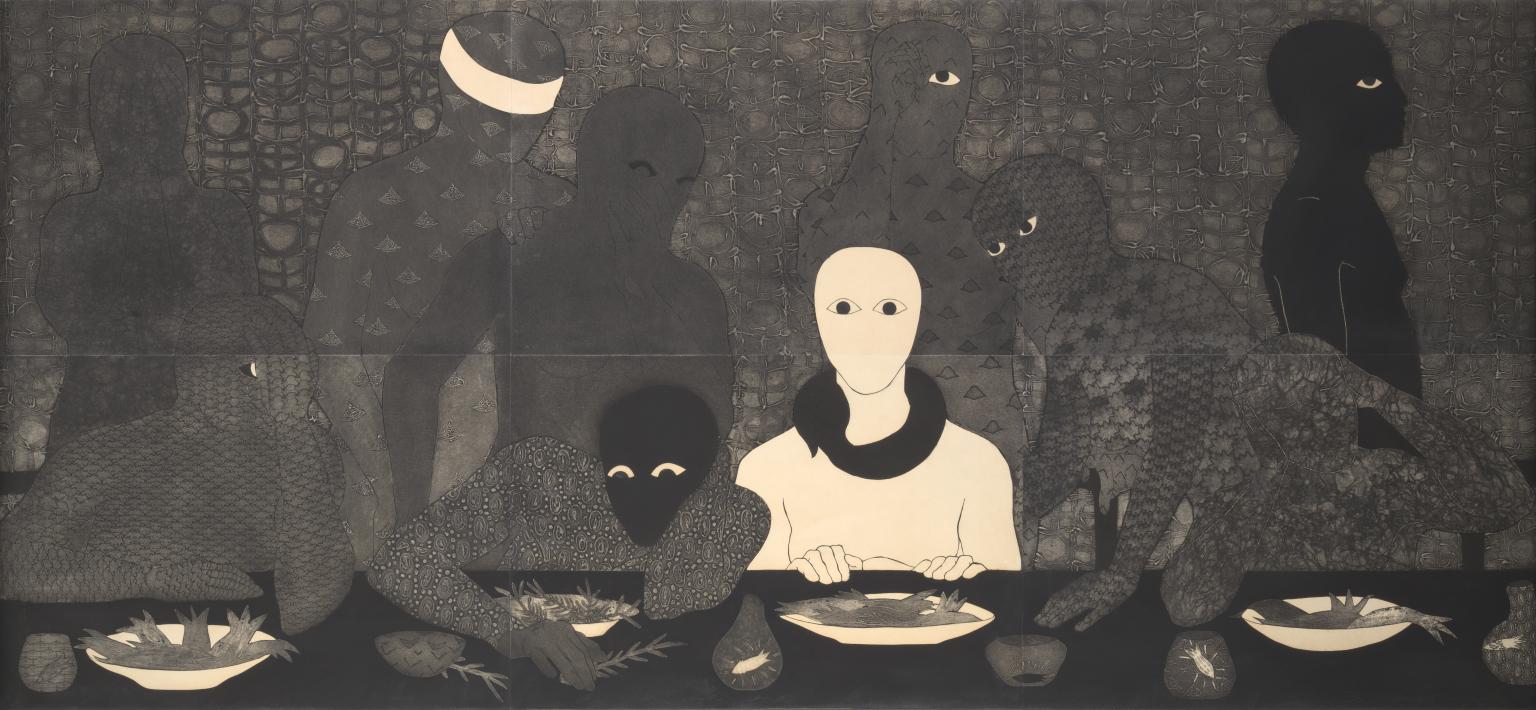

Ayón was a Cuban printmaker who specialised in a technique called collography. To create a printing plate, she glued various materials – from sandpaper to vegetable peelings – onto cardboard. Once inked, the plate was used to imprint the design onto paper.

Throughout her life, Ayón created allegorical scenes based on Abakuá, a secret, Afro-Cuban brotherhood. Abakuá is part of a belief-system brought to Cuba by enslaved people from southern Nigeria and Cameroon during the transatlantic slave trade. It became one of Cuba’s main religious-cultural groups.

Ayón centres the only female character, Princess Sikán, connecting her with the struggles of women in patriarchal societies: ‘Sikán’s image is paramount in all these works because, like myself, she led and leads a disquieting life, looking insistently for a way out.’

Born in Jamaica, Moody moved to London in 1923. He made carved works, inspired by sculptures he saw in local museums’ collections. Moody said his work Midonz represents the goddess of transmutation. She is in the process of changing from physical matter into spiritual form. The artist’s niece commented that Midonz epitomises a ‘tremendous inner force’ and the mysterious air of spiritual devotion often visible in figures of Egyptian art.

Like Ayón with Sikán, Moody here depicts and celebrates women as powerful, transcendent figures within spiritual and cultural narratives.

Art in this room