Meraud Guevara, Seated Woman with Small Dog c.1939. Tate. © Estate of Meraud Guevara.

Studio Practice

9 rooms in In the Studio

Discover how art can reflect the circumstances and spaces in which it is made

For many artists, the studio is a place where they can shut out any distractions, allowing an intense focus of attention. Some choose their own studio as a subject or depict fellow-artists at work, bringing the private experience of art-making into the public space of the gallery.

The works here include subjects that have been explored by western artists in their studios for hundreds of years: objects arranged for a still life, portraits and nudes. Often these subjects are submitted to a process of painstaking observation, but invention and imagination also play a crucial role. In the work of Georges Braque and the other artists associated with cubism, the close scrutiny of familiar items prompted an analysis of the whole act of looking, taking visual impressions apart and re-ordering them on the canvas. A generation later, Anthony Caro also approached still life in a fresh and experimental way in his sculpture.

Some artists keep their works around them and return to them again and again. Henri Matisse worked through four versions of his Back sculpture over twenty years, keeping the final version in his studio until his death. Such works become a diary of changing approaches and practices.

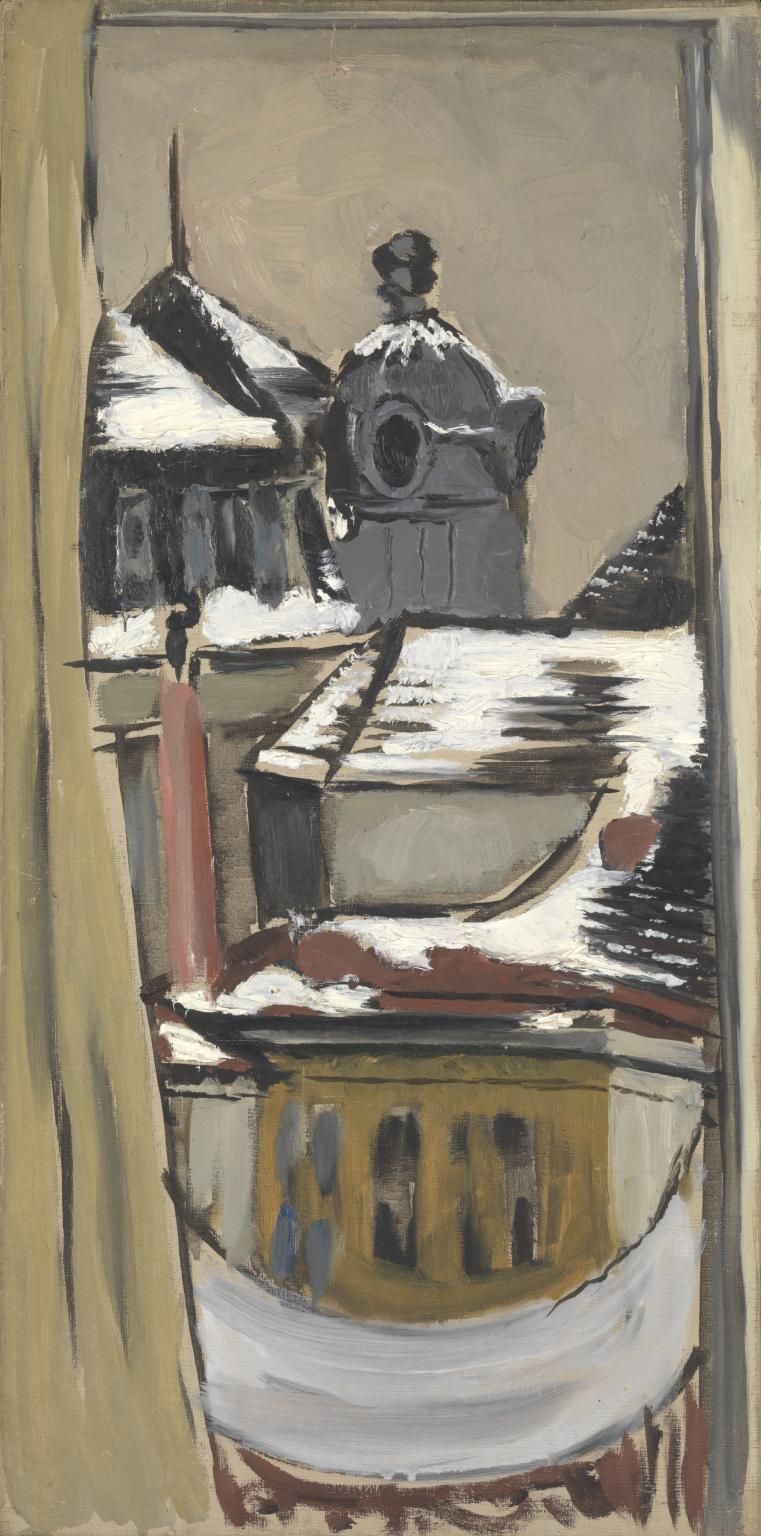

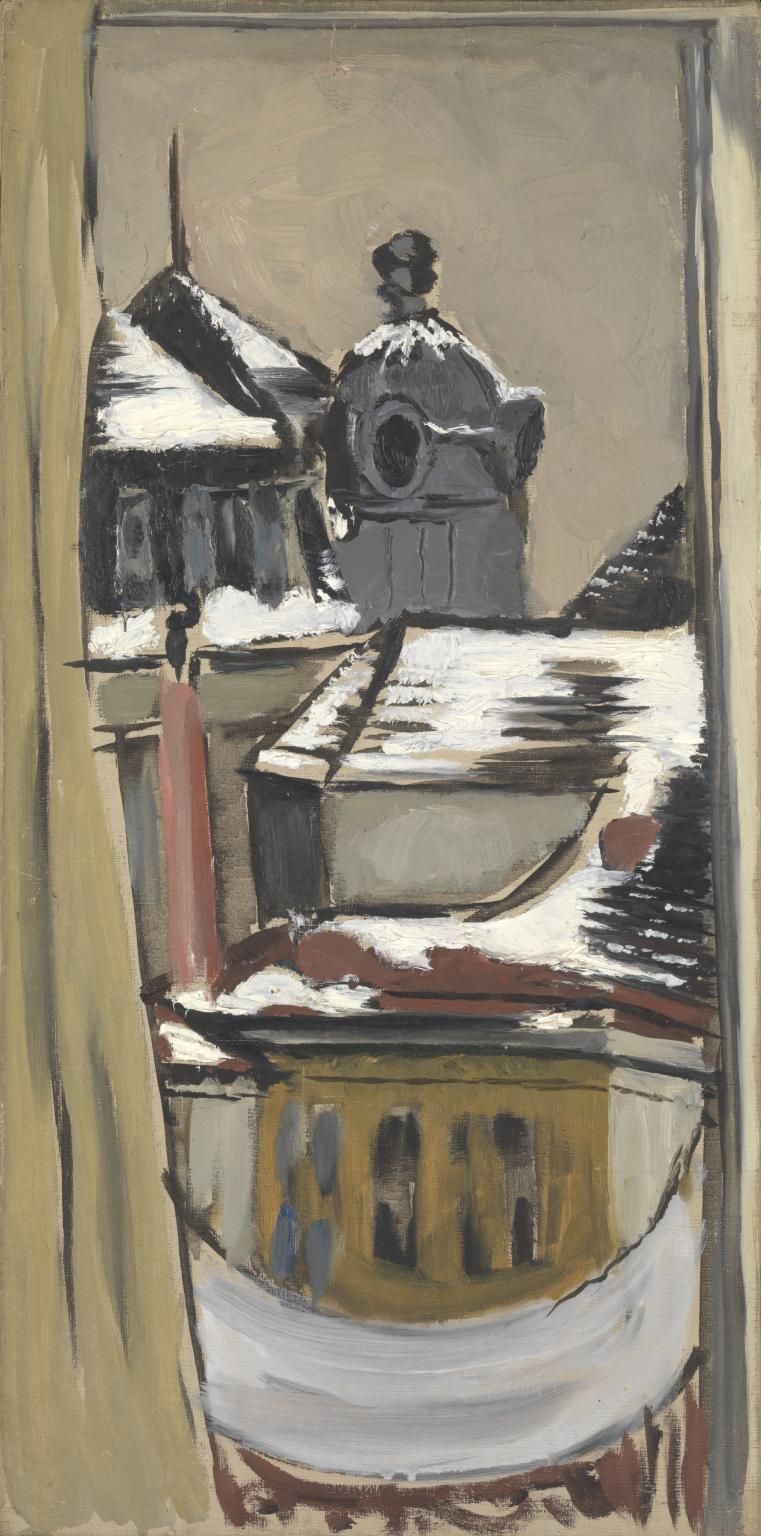

Marie-Louise Von Motesiczky, View from the Window, Vienna 1925

This painting depicts a view of roofs and facades seen from the artist’s fourth-floor flat in Vienna, where she lived during the first half of the 1920s. The cupola in the upper centre of the painting is part of the Johann Strauss Theatre, famous for its performances of light opera. Technically this painting makes a shift in the artist’s work. Previously she had applied paint in dabs which created a mottled effect. This work is painted with rather freer brush strokes. The elongated vertical format is characteristic of von Motesiczky’s canvases of the period.

Gallery label, October 2016

1/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Marie-Louise Von Motesiczky, Still Life with Sheep 1938

This was painted in a small hotel in Amsterdam. Von Motesiczky, and her mother, who were Jewish, fled to the city from their home in Vienna following the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, in 1938. She posed objects on an ironing board, the most convenient surface available to her. The two eighteenth-century Chinese sheep ornaments were ‘familiar from our Viennese surroundings’. Von Motesiczky later recalled her motivation ‘to paint something beautiful...to paint and to dream’.

Gallery label, February 2022

2/21

artworks in Studio Practice

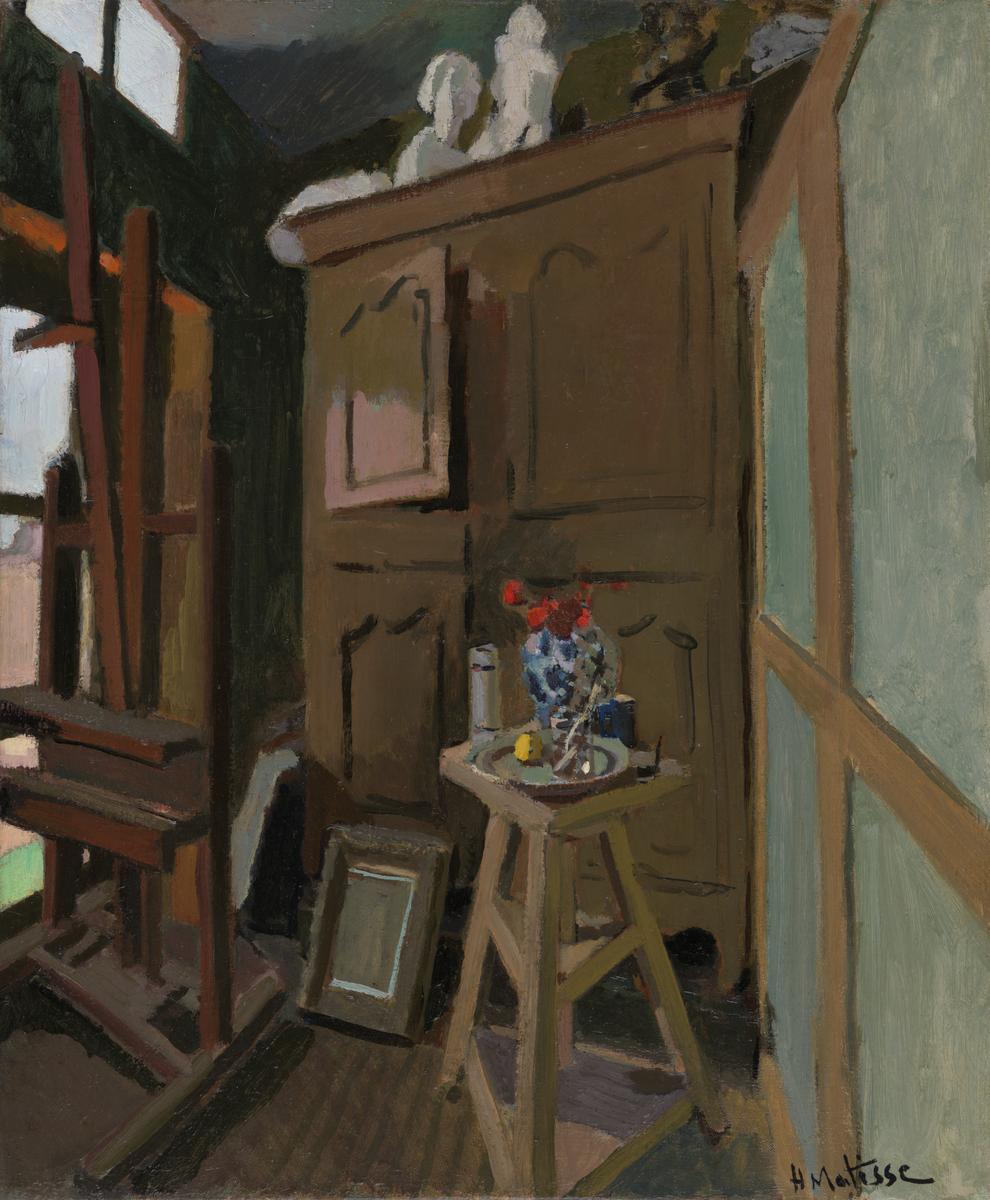

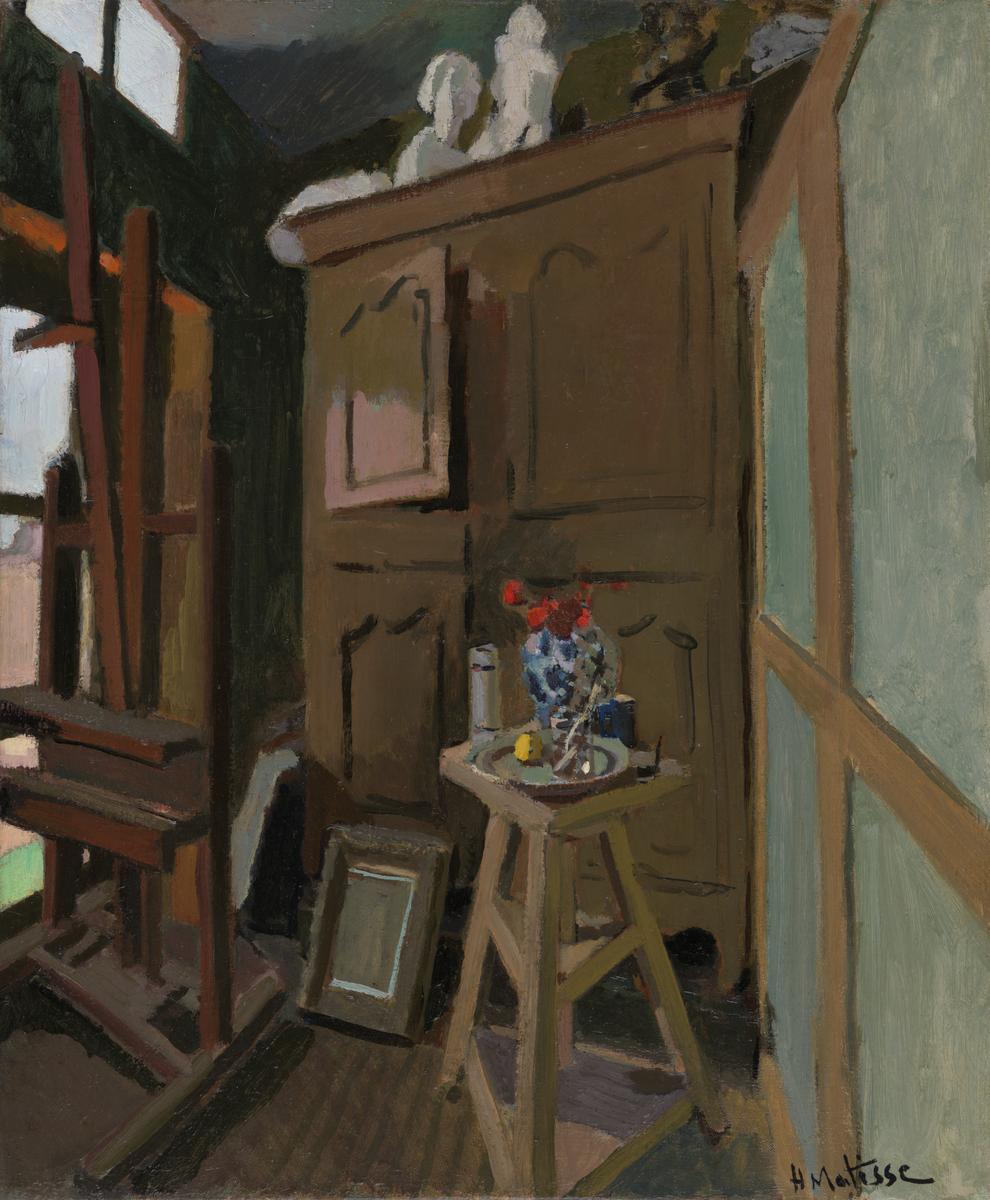

Henri Matisse, Studio Interior c.1903–4

This painting shows a corner of Matisse’s apartment in Paris, where he lived from 1899 to 1907. The subjects of domestic interiors and still lifes (such as the carefully arranged objects on the small stand here) were typical of Matisse’s works of the time. The sculpture casts on top of the wardrobe were his own work. He was attending life drawing and sculpture classes and much of his work in this period focuses on subject matter relating to his studio.

Gallery label, October 2016

3/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Georges Braque, Glass on a Table 1909–10

Traditional painting often presents a single viewpoint. Artists like Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso explored new ways of representing reality. They brought different views together in the same picture. The resulting paintings appear fragmented and abstracted. They imitate the fleeting nature of sight. In this painting of a glass and pears on a table, these different perspectives might appear to obscure the subject matter. But Braque believed that by breaking up familiar items and re-ordering them, he could get closer to a true likeness of the object.

Gallery label, July 2019

4/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Fernand Léger, Still Life with a Beer Mug 1921–2

Léger believed that art should be accessible to all. He moved away from pure abstraction and towards the stylised depiction of real objects. He put great emphasis on order, clarity and harmony. In the 1920s, he developed an interest in geometric compositions. This painting shows a relatively naturalistic still life of a workman’s lunch on a table. The primary colours of the mug and tablecloth contrast with the black and white patterns in the background

Gallery label, June 2021

5/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Georges Braque, Mandora 1909–10

Braque’s interest in collecting musical instruments is captured in this painting. Here he depicts a small stringed instrument called a madora. The painting is made up of different geometric shapes, making it appear fragmented. This style suggests a sense of rhythm, matching the musical subject of the painting. Braque explained that he liked to include instruments in his cubist works. ‘In the first place because I was surrounded by them, and secondly because their plasticity, their volumes, related to my particular concept of still life’.

Gallery label, August 2020

6/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Amedeo Modigliani, The Little Peasant c.1918

This is one of a small group of paintings that Modigliani made of young people. The artist inscribed the work's title on the bottom right of the canvas, identifying the sitter as a 'peasant boy'. However, there is some doubt over the accuracy of the title. The same model seems to appear in another painting titled 'The Young Apprentice'. Modigliani had long been influenced by the painter Paul Cézanne (1839–1906). This painting was probably inspired by Cézanne's paintings of country workers. Cézanne’s subjects were also positioned in the centre of the canvas and painted in mostly blue tones.

Gallery label, August 2020

7/21

artworks in Studio Practice

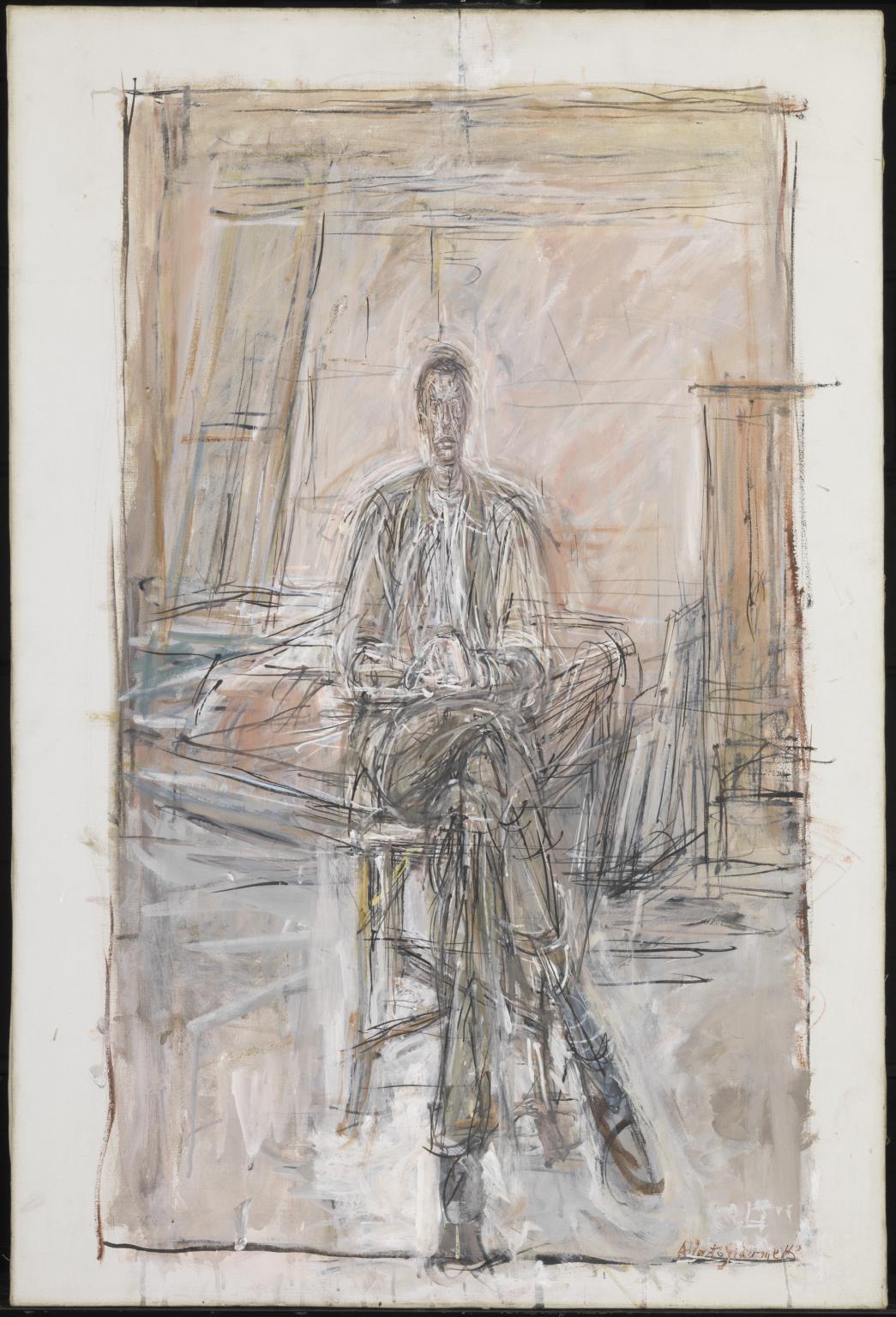

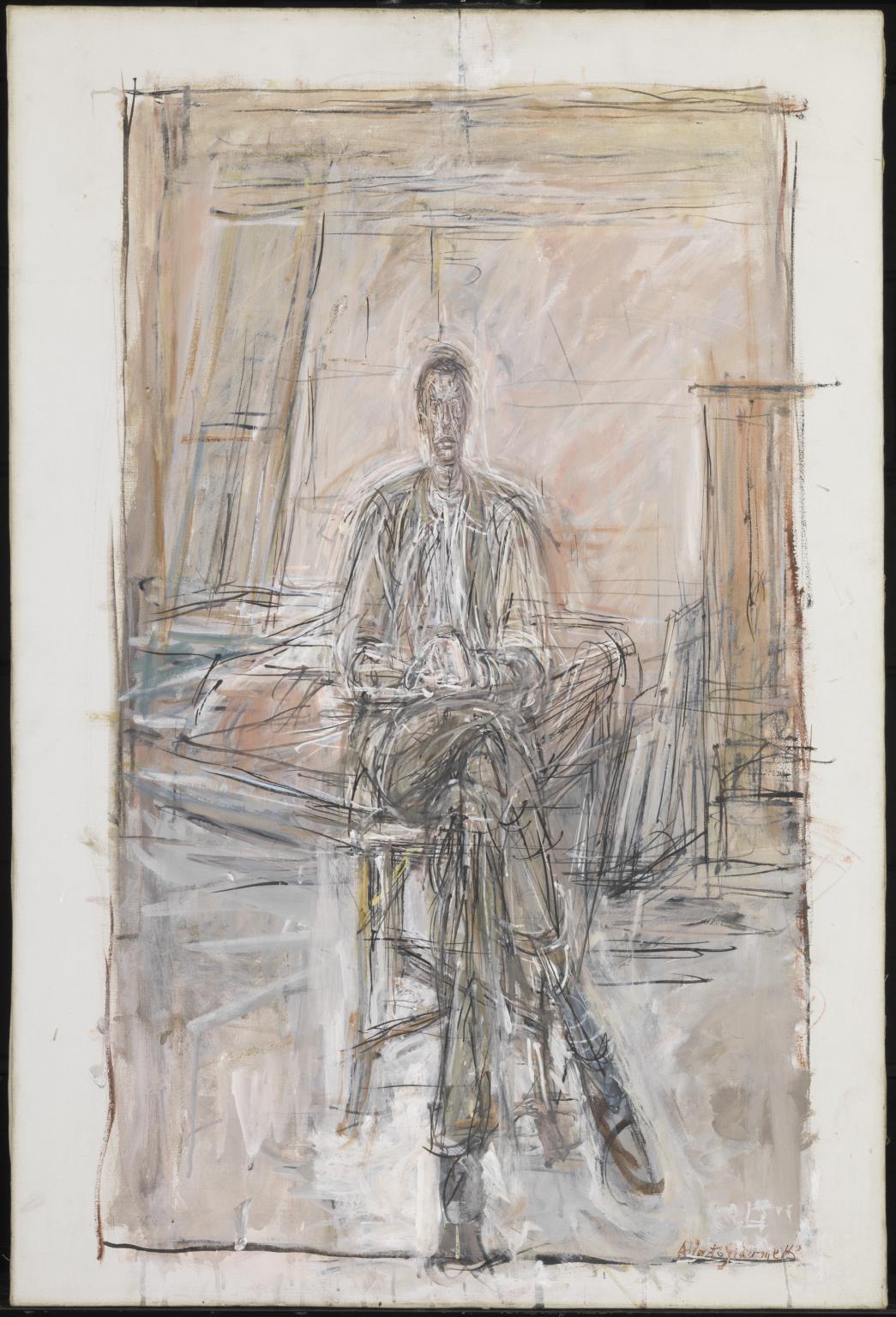

Alberto Giacometti, Seated Man 1949

Like his sculptures, Giacometti’s portraits emerged from an intense scrutiny of his subjects, and a process of continually reworking the image in order to record his shifting visual impressions. Seated Man depicts his brother Diego, one of Giacometti’s most frequent models, but even this familiar face became an object of investigation and discovery for the artist, who commented ‘When he poses for me I don’t recognise him’.

Gallery label, July 2012

8/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Alberto Giacometti, Interior 1949

9/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Marie Laurencin, Portraits (Marie Laurencin, Cecilia de Madrazo and the Dog Coco) 1915

Laurencin painted this portrait using simplified forms and a limited palette of blue, pink and grey. The artist was part of a group of cubist painters working in Paris around 1911. She chose, however, not to follow the abstracted treatment of the body that many of her cubist friends adopted. This picture was painted in Madrid in 1915. Laurencin moved to Spain with her husband, German painter Otto von Wätjen, following the outbreak of the First World War. It depicts Cecilia, the daughter of the Spanish painter Federico de Madrazo, and the artist herself, shown on the left.

Gallery label, September 2019

10/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Georges Braque, Guitar and Jug 1927

Braque used traditional artists’ props such as guitars, jugs and glasses to experiment with composition. The familiar objects in Guitar and Jug are presented in sombre colours of brown and grey. He uses fluid lines to create the objects, their softness set against a rigorous structure. The items may also have symbolic meaning. The guitar may suggest artistic harmony. The apples, branch and glass could celebrate the abundance of nature. Braque’s interest in depicting a variety of materials and textures is also clear. In this work he includes wood, glass, fabric, organic elements and wallpaper.

Gallery label, August 2020

11/21

artworks in Studio Practice

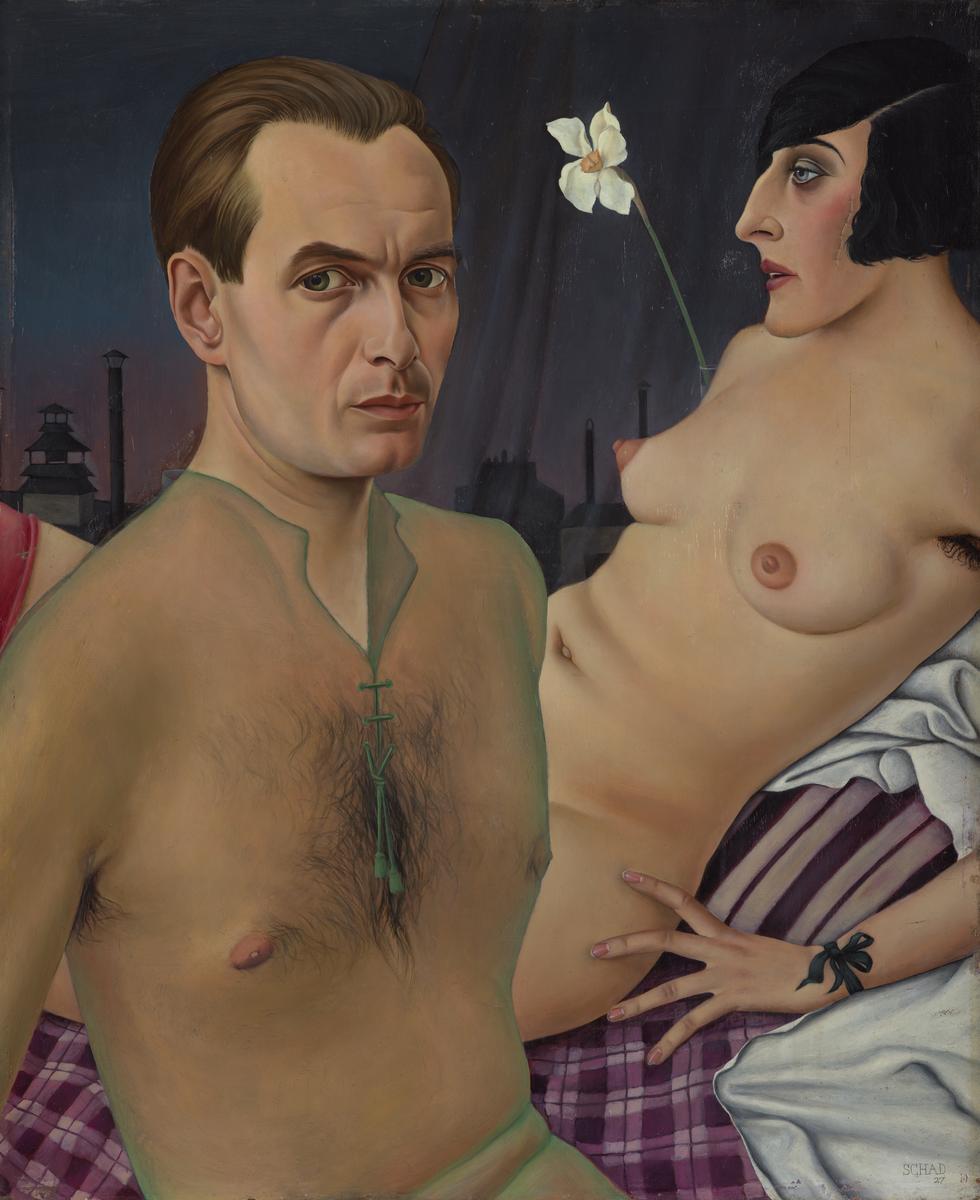

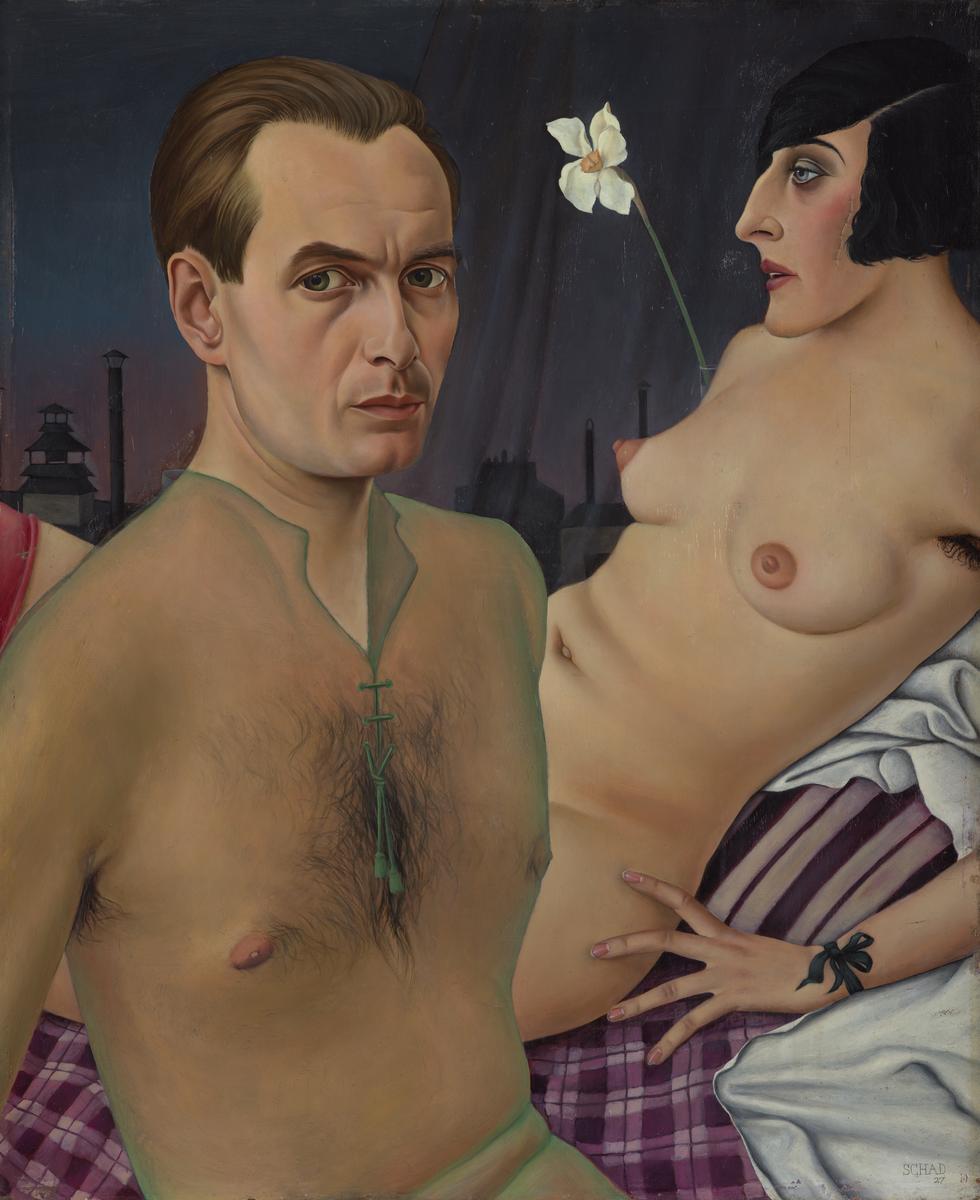

Christian Schad, Self-Portrait 1927

Schad claimed that 'no-one is entirely free from narcissism.' This self-portrait is loaded with symbols connected to identity and appearance. The artist is positioned in front of the woman, but only partially conceals her nakedness. In contrast to the naked woman, Schad wears a transparent shirt. A narcissus flower, indicating vanity, leans towards the artist. The woman’s face is scarred with a sfregio, a wound inflicted as a punishment by Neapolitan criminals. The work contains violent and erotic suggestions. Despite this, Schad said, 'it is not about the aftermath of heat and passion but is meant as an allegory of narcissism.’

Gallery label, August 2020

12/21

artworks in Studio Practice

David Smith, Home of the Welder 1945

Home of the Welder was made shortly after the Second World War. The work reflects Smith’s personal circumstances. He had just been released from his wartime job as a welder, which he believed had restricted his creative work. The various elements in the sculpture relate to his dreams and frustrations at the time. It can be seen as Smith's coded diary. The millstone was identified by Smith as representing his job as a welder. The images of women and children may reflect tensions in his first marriage, from which he did not have children.

Gallery label, August 2020

13/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Alice Neel, Ethel Ashton 1930

Lent by the American Fund for the Tate Gallery, courtesy of Hartley and Richard Neel, the artist's sons 2001L02332 Ethel Ashton, 1930, was painted at one of the most trying times in Alice Neel's life. In May of that year her husband, the Cuban artist Carlos Enríquez (1900-1957), had left her, moving out of their New York apartment and taking their daughter Isabella (called Isabetta, 1928-1982) to Havana to be raised by his two sisters. Penniless, Neel was forced to sublet the apartment and move back to her parents' home in Colwyn, Pennsylvania. Every day she would travel to Philadelphia to work at the studio of Ethel Ashton (1896-1975) and Rhoda Meyers, two friends from the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College of Art and Design), where Neel had studied between 1921 and 1925. In mid-August Neel suffered a nervous breakdown and by October she had been hospitalised in Philadelphia. Of this time Neel later wrote, 'I worked at their studio every day. You can't imagine how I worked. I wouldn't have carfare; I wouldn't have enough for lunch. I had a terrible life.' ('Alice on Alice', in Patricia Hills, New York 1983.) In the short space of time that she worked in Meyers's and Ashton's studio, however, Neel painted a number of important early works, including portraits of both her friends, Rhoda Meyers with Blue Hat, 1930 (private collection), and Ethel Ashton. Neel was frustrated by the marginalised status of women artists and her nude portraits of Ashton and Meyers as painted models rather than artists in their own right deliberately court and complicate stereotypes of women. Neel painted Ashton as a large, ungainly and hesitant looking figure. The deliberate awkwardness of the painting recalls the Expressionism of Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1884-1976) or even the sculptures and prints of Ernst Barlach's (1870-1938). The position of the artist in relation to the sitter, above and off-centre, results in the distortion of the latter's body and features, emphasising her sagging fleshiness. Bright white light coming from the right of the painting accentuates the misshapen folds of flesh and gives the body an air of substantial, almost sculptural, bulkiness. The cropping of the figure and shallow setting add to a sense of anxiety; the overall effect is that of a reluctant, cornered goddess of fertility caught in the headlights of a vehicle. 'Don't you like her left leg on the right, that straight line?' Neel later wrote. 'You see, it's very uncompromising. I can assure you, there was no one in the country doing nudes like this. And also, it's great for Women's Lib, because she's almost apologizing for living.' (Quoted in Alice Neel: Paintings from the Thirties, 1997, p.66.) The painting itself is not apologetic; it is confident and uncompromising. It offers the viewer an uncomfortable but strongly depicted image of femininity. Curator Ann Temkin, discussing Neel's 1980 Self-portrait (private collection), describes it as 'not calculated to please anyone, least of all the misshapen sitter', adding, 'like much of Neel's work over the course of five decades, the painting is happy to look wrong.' ('Alice Neel: Self and Others', in Temkin, ed., 2000, p.13.) This is a description that could as easily be applied to Ethel Ashton. Further reading:Patricia Hills, Alice Neel, New York 1983, reproduced p.31 in colourDenise Bauer, 'Alice Neel's Female Nudes', Woman's Art Journal, volume 15, number 2, Fall 1994/Winter 1995Alice Neel: Paintings from the Thirties, exhibition catalogue, Robert Miller Gallery, New York 1997, reproduced p.67 in colourAnn Temkin (ed.), Alice Neel, exhibition catalogue, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia 2000 Giorgia BottinelliMarch 2002

14/21

artworks in Studio Practice

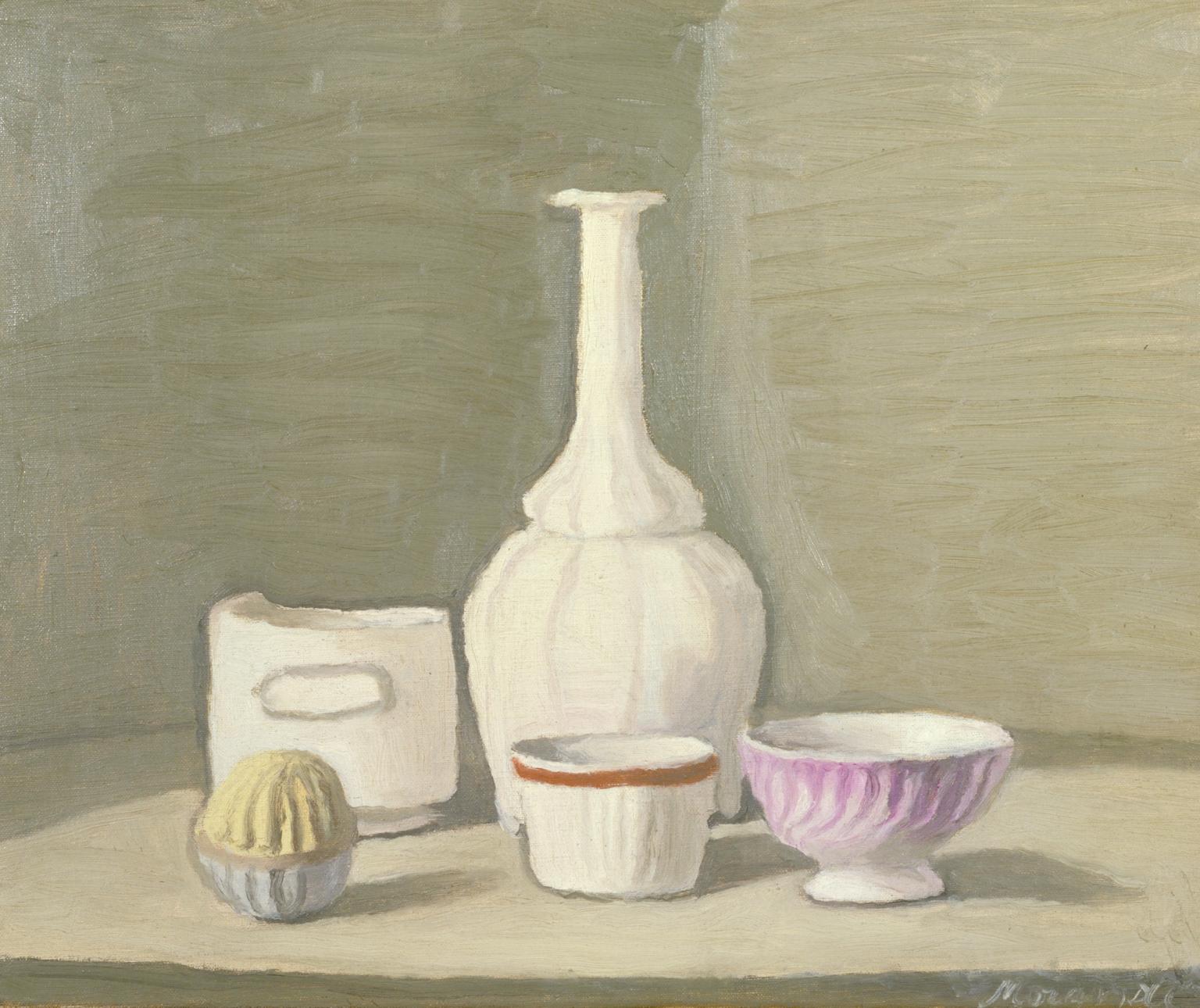

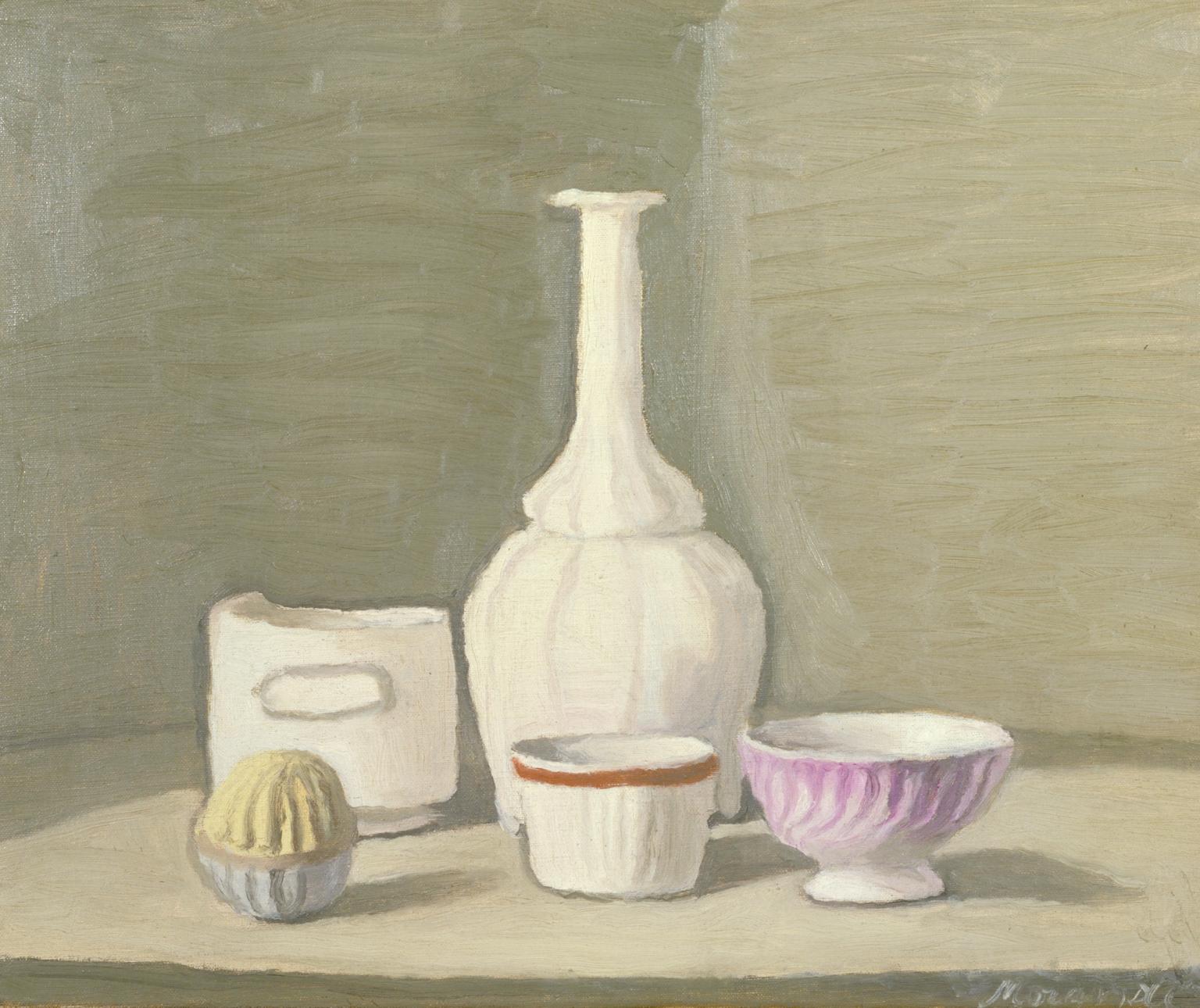

Giorgio Morandi, Still Life 1946

Morandi’s still life features a number of household objects. He often included the same selection of familiar items in his works. He kept a supply of vases, bottles and jars in his studio to use in his still life paintings. In this work, the objects lose their domestic purpose, becoming sculptural objects. Through repeated studies of the same items, Morandi creates a sense of timelessness. His use of earthy and muted colours was inspired by his native Bologna in northern Italy. This connects the artist's paintings to his own life and surroundings.

Gallery label, August 2020

15/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Christian Schad, Agosta, the Pigeon-Chested Man, and Rasha, the Black Dove 1929

The people in this painting directly return our gaze. Schad met the two sitters at a funfair in north Berlin in 1929. They were performers in a sideshow act there. Their roles involved displaying their bodies as ‘exotic’ or ‘other’ to funfair visitors. We might ask whether the painting is critical of this objectification. It could also be seen as perpetuating the voyeurism and discrimination experienced by Agosta and Rasha. Schad's commitment to painting reality reflects his association with the New Objectivity. This artistic movement combined social criticism with a near-photographic realism.

Gallery label, August 2020

16/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Sir Anthony Caro, Table Piece CCLXVI 1975

Table Piece CCLXVI is constructed on a human scale. At just over two metres wide it is comparable to the width of a person’s outstretched arms. Caro has observed that: ‘all sculpture is to do with the physical – all sculpture takes its bearings from the fact that we live inside our bodies and that our size and stretch and strength is what it is’.

Gallery label, October 2016

17/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Georges Braque, Clarinet and Bottle of Rum on a Mantelpiece 1911

A horizontal clarinet lies on top of a mantelpiece at the centre of this playful, geometric work. In front stands a bottle with the characters RHU, the first three letters of the French word for rum. The word VALSE (waltz) indicates sheet music, reinforced by fragments of treble and bass clefs found throughout the image. A scrolled form in the lower right could represent part of the mantelpiece, or a violin-head. Braque painted this during a summer he spent with Picasso in the Pyranees. They worked together depicting similar scenes and objects in the same style.

Gallery label, April 2022

18/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Natalia Goncharova, Gardening 1908

The decorative, stylised quality of this work reflects Goncharova’s interest in the folk arts and religious icons of her native Russia. While contemporaries were looking to so-called ‘primitive’ art beyond Europe, Goncharova celebrated Russia’s indigenous culture. She explained: ‘If I extol the art of my country, then it is because I think that it ... should occupy a more honourable place than it has done hitherto.’ This work is typical of her depictions of peasant life and was made around the time of her stay on a family estate in rural Russia.

Gallery label, March 2005

19/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Meraud Guevara, Seated Woman with Small Dog c.1939

The woman in this painting dominates the steep, angled space. She would not fit in the interior if she were to stand. This creates a sense of uncertainty for the viewer. Guevara made a number of precise and realistic paintings of women, in which they dominate the space. This gives the viewer a strange and uneasy perspective. Here, a sense of mystery is suggested by the imaginary view. This is achieved by placing the room high above the landscape, the open doorway behind, and the strange, but deliberate, flash of orange beside the door.

Gallery label, April 2021

20/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Alvaro Guevara, Dame Edith Sitwell 1916

The sitter, Edith Sitwell (1887-1964) was the daughter of Sir George Sitwell, 4th Baronet, and sister of Sir Osbert and Sachaverell Sitwell. She was a poet and at the time of this portrait she was editor of 'Wheels', an annual anthology of new poetry published between 1916 and 1921. Edith Sitwell is seated on an Omega Workshops dining chair, a modern piece of furniture designed by the painter and art critic Roger Fry, who ran his decorative arts venture, the Omega Workshops, from 33 Fitzroy Square, London, in the heart of Bloomsbury. Both Edith Sitwell and Alvaro Guevara patronised the Omega Workshops.

Gallery label, August 2004

21/21

artworks in Studio Practice

Art in this room

You've viewed 6/21 artworks

You've viewed 21/21 artworks