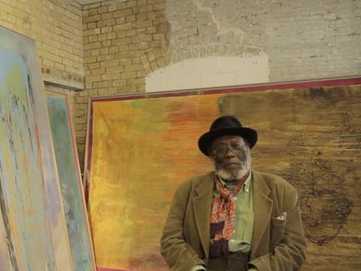

Frank Bowling in his New York studio, 1970

Frank Bowling Archive

The possibilities of paint are never-ending

— Frank Bowling, 2017

Over the past 60 years, Frank Bowling (born 1934) has relentlessly explored the properties and possibilities of paint. He has experimented with staining, pouring and layering, adopting a variety of materials and objects. Throughout his career, Bowling has investigated the tension between geometry and fluidity. His large, ambitious paintings are known for their distinctive textured surfaces and colourful, luminous quality.

This is the first full retrospective exhibition dedicated to Bowling. It covers each phase in his long and sustained career. Beginning with his early figurative paintings, created in London in the early 1960s, it traces the progress of his work as he relocated to New York, US in 1966. Here, his paintings became increasingly abstract, without relinquishing references to his personal life. For many years Bowling lived and worked between New York and London. Both cities have had an impact on his work, alongside his childhood home in New Amsterdam, Guyana. The exhibition goes on to feature the ‘map paintings’, the ‘poured paintings’ and works from the Great Thames series. It ends with his most recent canvases in which his experiments continue.

At 85 years of age, Bowling still paints every day. His work relies on technical skill while embracing chance and the unpredictable. Bowling’s paintings embody his ongoing pursuit of change, transformation and renewal.

Room 1

Early Work: Life, Politics and Personal Narratives

Frank Bowling was born in 1934 in Guyana (then British Guiana), South America. In 1953 he left his home town New Amsterdam and travelled to London. He arrived here during the celebration for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. After some early attempts at poetry and two years of service in the Royal Air Force, Bowling enrolled at the Royal College of Art, London. From 1959 to 1962 he studied painting alongside a talented and ambitious group of students. These included artists Derek Boshier, David Hockney and R.B. Kitaj.

Bowling’s early work demonstrates his interest in social and political issues as well as personal narratives. It often depicts painful memories and disenfranchised individuals. During this time Bowling started to use both figuration and abstraction in his work. Adopting the theme of a dying swan, he began to explore formal concerns. He used principles of geometry to shape the canvas and structure the composition. He also began to study colour theory and juxtapose planes of bold colours.

Room 2

Sir Frank Bowling OBE RA

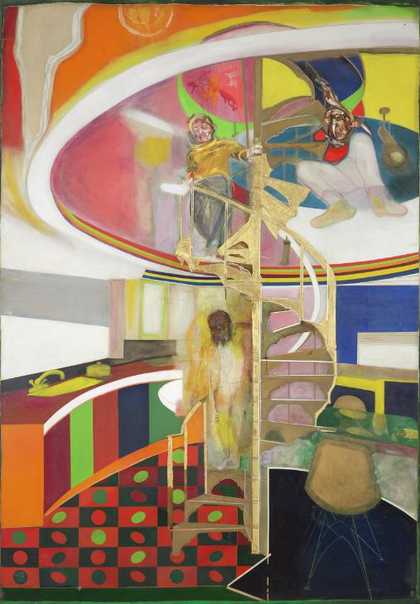

Mirror (1964–6)

Tate

Photographs into Paintings

Between 1964 and 1967, Bowling brought together many different pictorial approaches, sources and techniques. This was a period of great change in his life and career. In 1966, he moved from London to New York, and was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship the next year. This enabled him to establish himself in the US, where he spent most of the following decade.

Bowling continued to use figurative elements in his work. Some are expressionistic, painted in a gestural manner. Others are more graphic, rendered through printing techniques. Bowling adopted different images as sources for his figures. These include photographs of scenes he staged, family pictures and images from magazines. A silkscreened image of his family home in New Amsterdam became a central element in his paintings. His mother built the house for her family, who occupied the upper floors, and her business, Bowling’s Variety Store, situated on the ground floor. From 1966–7, Bowling also began to use stencils in his work, and the first outlines of continentlike shapes appear. These works signal his ongoing interest in geometry, intuitive use of bold planes of colour and exploitation of the unpredictable nature of paint.

Room 3

Frank Bowling

South America Squared 1967

Rennie Collection, Vancouver

The Map Paintings

Soon after moving to New York in 1966, Bowling stopped painting the human figure. He began working on a group of paintings characterised by their scale, fluid application of acrylic paint and luminosity. Additionally, through his writing in Arts Magazine (1969–72), Bowling played a key role in debates around ‘Black Art’. He championed the rights of artists to engage in any form of artistic expression, irrespective of their identity or background.

The works in this room, referred to as the ‘map paintings’, date from 1967–71. Fields of colour are overlaid with stencilled maps of the world and silkscreened images. Bowling worked on unstretched canvases, placing them on the floor and on the wall. He applied paint by staining, pouring and spraying. The southern hemisphere often dominates these canvases. This focus marks Bowling’s rejection of the westerncentric cartography of many world maps. Images of the artist’s mother and children are among those silkscreened onto some of the canvases. The results are complex, layered artworks. These ‘map paintings’ reveal Bowling’s interest in the way identities are shaped by geo-politics and displacement.

Room 4

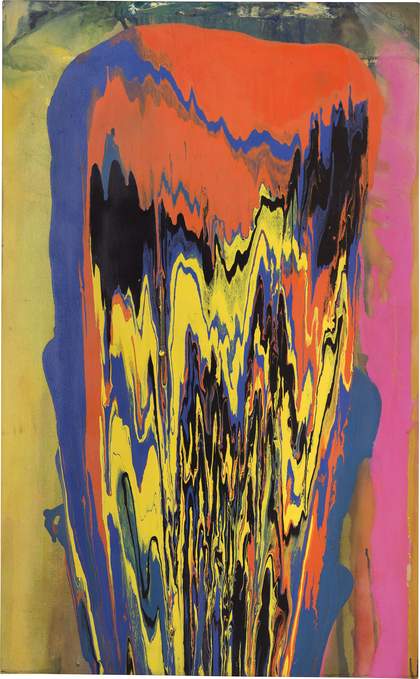

Frank Bowling

Tony's Anvil 1975

Private collection, London, courtesy of Jessica McCormack

© Frank Bowling. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2019

Frank Bowling

Ziff 1974

Private collection, London, courtesy of Jessica McCormack

© Frank Bowling. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2019

The Poured Paintings

Around 1973, Bowling began pouring paint on to canvases to produce layered effects of contrasting colours. The resulting paintings reveal the processes of their making. They were Bowling’s personal response to the challenges of formalism in modernist painting, a critical stance promoted by the American art critic Clement Greenberg. It suggested that the visual aspects of an artwork are more important than narrative content. Greenberg supported Bowling’s work and the two were friends.

In his New York and London studios, Bowling built a tilting platform that allowed him to pour paint from heights of up to two metres. The spilling paint created an energetic and innovative painting style. These ‘poured paintings’ were the result of controlled chance. They reveal Bowling’s interest in the tension between a structured approach to painting and accidental developments.

During this time Bowling’s artwork titles become increasingly enigmatic. Bowling names a painting once it is finished, attempting to reconnect with what took place during its making. Titles often allude to aspects of the artist’s daily life, referencing people and personal associations. Yet they remain ambiguous, preventing a prescriptive reading of his work.

Room 5

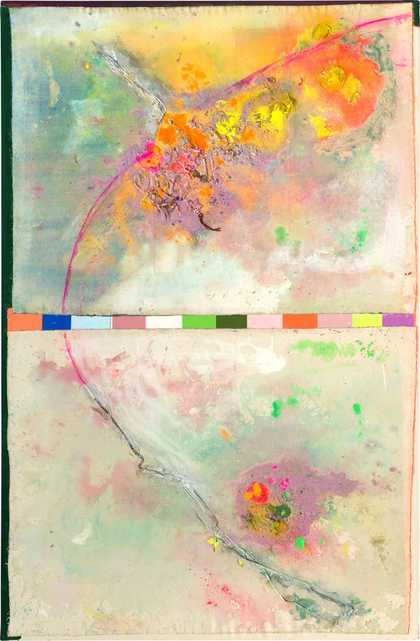

Frank Bowling

Ah Susan Whoosh 1981

Private Collection, London

Cosmic Space

By the end of the 1970s, Bowling was fully in control of the painting techniques he had spent the last ten years fine-tuning. He had a deep understanding of the dynamics of the flow of paint and the drama of colour combination. In need of new challenges, he adopted a variety of interventions. Bowling began using ammonia and pearlessence, and applied splotches of paint by hand, producing marbling effects. He embraced accidents, allowing him to achieve unexpected results. For example, the round imprint of a bucket, left to rest on a drying canvas, contributed to the composition of Vitacress 1981 and became a recurring device.

The paintings displayed in this room might make us think of atmospheric impressions of skies, visions of the world and the cosmos, or alchemical transformations. Bowling doesn’t create works with these references in mind. However, he welcomes different responses and interpretations from viewers.

Room 6

Sir Frank Bowling OBE RA

Spreadout Ron Kitaj (1984–6)

Tate

More Land than Landscape

In the 1980s, Bowling continued to explore the colour and structure of his compositions, but now added his latest experiments building up textures on the surface.

Bowling began mixing acrylic paint with acrylic gel. This material is similar to acrylic paint, but without the colour pigment. Bowling used acrylic gel to extend the volume of paint, create greater texture, and add transparency. Additionally, he used acrylic foam. He cut the material into thin strips, to create linear accents and suggest loosely geometric shapes. He also started to use a range of other materials and objects in his work. He applied metallic pigments, fluorescent chalk, beeswax and glitter to his densely textured surfaces. In several works, found objects such as plastic toys, packing material, the cap of a film canister and oyster shells are embedded within the paint. These items are rarely fully visible but add to the complexity and mysterious quality of his works.

The diverse materials and objects in these paintings invite us to pay attention to their materiality. The works extend towards the viewer, prompting a more physical engagement. While it has often been said that these paintings suggest landscapes and seascapes, the painter Dennis de Caires stated that they are ‘more land than landscape’ and ‘portray the marriage of man to the physical world’ (1986).

Room 7

Frank Bowling

Sacha Jason Guyana Dreams 1989

Tate. Purchased 2006

Water and Light

This room brings together four paintings completed in 1989. They demonstrate Bowling’s engagement with both the gestural handling and expanses of colour of abstract expressionism and with his interest in English landscape painting.

Two of the paintings belong to the series Great Thames, made in Bowling’s studio in East London, close to the river Thames. These paintings capture the play of light on the water, changing with the time of the day and the seasons. They are some of Bowling’s most poetic paintings and hint at the work of the English landscape artists he deeply admires, particularly Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788), J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) and John Constable (1776–1837).

When Bowling travelled back to New Amsterdam in 1989, he recognised the particular light of Guyana had also been key to his painting. He stated: ‘When I looked at the landscape in Guyana, I understood the light in my pictures is a very different light. I saw a crystalline haze, maybe an East wind and water rising up into the sky. It occurred to me for the first time, in my fifties, that the light is about Guyana. It is a constant in my efforts’ (1992).

Room 8

Frank Bowling

Orange Balloon 1996

Courtesy Frank Bowling and Hales Gallery

Layering and Stitching

In the 1990s, Bowling continued to work with acrylic paint and gel, incorporating different materials and objects into his paintings. His interest in the painting as an object prompted him to stitch canvases together. He started to attach his main canvas to brightly-coloured strips of secondary canvas, which created a border. Bowling also began working on smaller paintings. For decades he had mostly worked on a large-scale, so these smaller format works offered a new challenge. He could experiment with the treatment of the support and use sections of the same canvas in different works.

Bowling began to work on more than one painting simultaneously. Sections of earlier cut-out canvases, with different paint applications and colours, would be stapled and glued together. The staples, which fix the different sections of the cloth together before the glue binds them, are records of the artist’s process. This technique enhances the materiality of the works, while also conveying a sense of ephemerality.

Room 9

Frank Bowling Iona Miriam's Christmas Visit To & From Brighton 2017 Courtesy Frank Bowling and Hales Gallery © Frank Bowling. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2019

Explosive Experimentation

Currently, at the age of 85, Bowling still works in his studio every day. This final section is dedicated to paintings made over the last decade. Despite working almost exclusively from a seated position, Bowling’s persistent need to reinvent painting carries on.

Bowling continues to experiment with techniques adopted over many decades, combining them into an infinite number of variations. We can see washes of thin paint, poured paint, blotched paint, stencilled applications, use of acrylic gels, insertion of found objects, and stitching of different sections of canvas. Bowling also continues to explore the two conflicting ideas of geometry and fluidity that have occupied him throughout his career. His compositions are based on overarching structures and loosely geometrical arrangements. At the same time, paint is mixed with a wide range of materials and objects and allowed to flow and spread across the canvas.

The paintings in this final room seem to have a particularly open-ended quality. Bowling’s technical mastery, acquired through decades of experimentation, gives way to a remarkable confidence to improvise. He continues to establish, and systematically break, an ever-changing set of self-imposed rules.