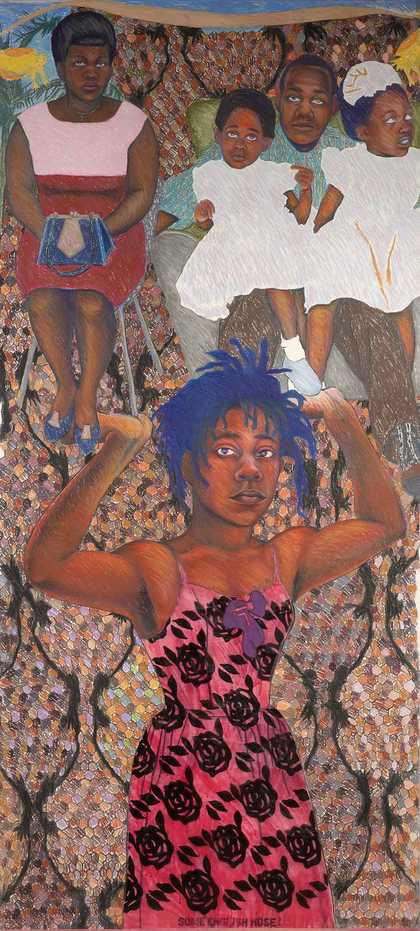

Sonia Boyce She Ain’t Holding Them Up, She’s Holding On (Some English Rose) 1986 Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Middlesbrough, UK) © Sonia Boyce. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2021

INTRODUCTION

Life Between Islands explores and celebrates the relationship between the Caribbean and Britain in art from the 1950s to today. Criss-crossing the Atlantic Ocean, it reconsiders British art history in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries from a Caribbean perspective.

Most of the artists represented are of Caribbean heritage: they were born in the Caribbean and came to Britain, either as adults or children, or were born of parents who settled in Britain. All of the artworks on display address the Caribbean in significant ways.

The exhibition is not a comprehensive survey of Caribbean-British art. While it is broadly chronological, each section examines different themes. These include the role of culture in decolonisation; the sociopolitical struggles that Caribbean-British people face; the social and cultural significance of the home; the reclaiming of ancestral cultures; and the cross-cultural nature of Caribbean and diasporic identity. The themes are explored across different art forms in a manner that is characteristic of Caribbean culture and thought.

Life Between Islands seeks to highlight the new identities, communities and cultural forms forged by Caribbean-British people. These developments have taken place in the face of hostility and discrimination, with defiance, solidarity, and creativity. The exhibition reveals the ways in which people of the Caribbean diaspora have created a distinctly Caribbean-British culture while influencing British society as a whole.

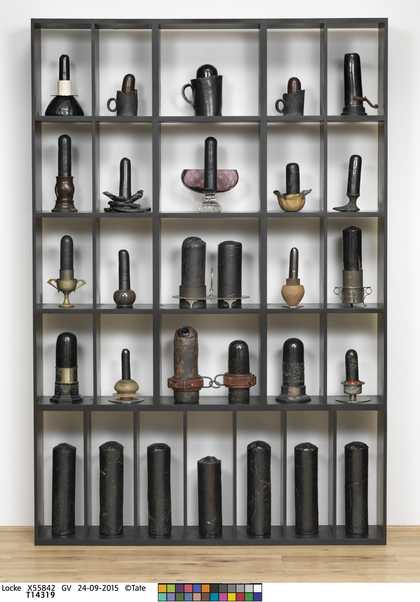

Donald Locke Thropies of Empire 1972-74 Tate. Purchased 2015 © Donald Locke

ARRIVALS

This exhibition begins with artists who travelled to the UK from the Caribbean. Most arrived between the late 1940s and the early 1960s. Some came to study, later developing careers as artists and writers. Most took advantage of the 1948 British Nationality Act inviting ‘Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies’ to ‘return to the mother country’. They joined the nearly half a million people leaving the British West Indies for Britain.

Coming from Barbados, Guyana (then British Guiana), Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and various other islands, these artists discovered a common identity in the UK. Writer George Lamming remarked, ‘we became West Indian in London’. Many Caribbean artists and writers advocated for the role of culture in decolonisation. They challenged the British colonial systems in which they had been born and raised and questioned the dominance of British cultural values. Artists made references to African and Indigenous Caribbean cultures through new abstract and symbolic forms. They consciously reclaimed a heritage that had been fragmented and erased by centuries of slavery and colonisation.

Collaborations across disciplines were a key feature of the period. Writers, artists and activists developed movements and collectives built on shared experiences and political solidarity. They drew attention to racial inequalities and pursued new Black identities and a modern Caribbean aesthetic.

Ronald Moody

Johanaan (1936)

Tate

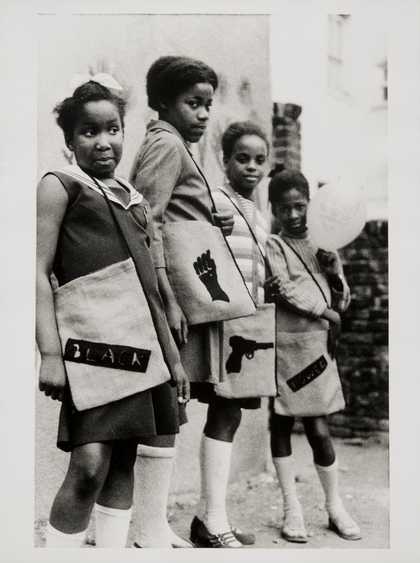

Neil Kenlock MBE

Black Panther school bags (1970, printed 2010)

Tate

PRESSURE

The artists in this section of the exhibition were either born in Britain or arrived as children. Many of their works confront racism head-on. They reflect on the Black British experience in the 1970s and 1980s: high unemployment, hostile media, police harassment, and violence and intimidation by far-right groups. However, like the large-scale uprisings of the 1980s, these works highlight more than the brutality and inequalities Black British communities faced. They signify collective power, community spirit and solidarity. They document the spaces in which Caribbean culture and people thrived.

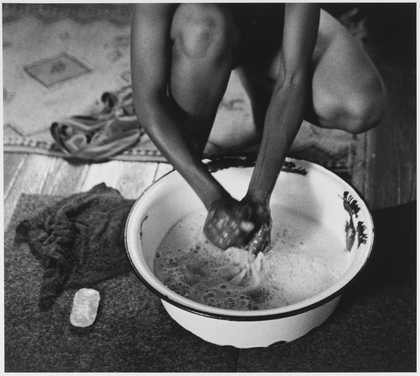

As unofficial ‘colour bars’ restricted access to public social spaces, homes became places of sanctuary. The front room, full of reminders of the Caribbean, became a site for inter-generational connection and somewhere to socialise with family and friends.

Sound systems provided the soundtrack to the period. DJs, engineers and MCs set up in homes, on the streets and in community centres. They offered a way to connect with culture coming out of the Caribbean, especially Jamaica. For young Black Britons, music created opportunities for collectivity and celebration but also a means to address hostility and discrimination with a spirit of defiance. Dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson named them the ‘Rebel Generation’.

The Black Arts Movement, that emerged in the 1980s, was deeply engaged with this socio-political moment. Artists from across Britain formed networks to offer support, strategise and debate. They worked in a range of mediums, exploring the politics of representation, often examining the ways in which race and gender intersect.

Denzil Forrester Jah Shaka 1983 Collection Shane Akeroyd, London © Denzil Forrester, courtesy of Stephen Friedman Gallery

GHOSTS OF HISTORY

The four artists in this room are associated with the Black Arts Movement of the 1980s and early 1990s. As well as addressing the urgencies of the here and now in Britain, these artworks invite us to consider continuities across time and place. They present colonialism and slavery as ongoing forces in the lives of British and Caribbean people.

The artworks shown here explore haunting ancestral presence in the former colonies of the British West Indies and tell stories of families separated by centuries of slavery and migration. They interrogate the ways in which the state and mass media uphold racist fears and fantasies of Black men, and the impact of surveillance, policing and policy on communities. They make links between the uprisings of the 1980s and the revolutions of enslaved people.

Together, these artists reveal how the past haunts, recurs and has legacies in the present.

CARIBBEAN REGAINED: CARNIVAL AND CREOLISATION

This fourth chapter of the exhibition explores the work of artists of our century. Here, the Caribbean returns as an explicit reference point and inspiration. Some works are inspired by the geography and ecology of Caribbean territories. Others take on Caribbean cultural forms, characterised by a blending of various traditions. They reflect on the Caribbean region’s position as a global crossroads.

Creolisation refers to the mixing of cultural influences and is a marker of Caribbean culture. It is closely related to syncretism, the act of combining different beliefs and practices, which is fundamental to African-based Caribbean religions. Many of the artworks in this section reflect on this mixing as the result of long, violent encounters between European, African, Asian and Indigenous Caribbean societies. However, they also demonstrate the dynamic and generative nature of these cross-cultural exchanges.

Carnival is the most well-known example of creolisation. Every Caribbean nation has its own version, whether it is called Carnival, Junkanoo, Jonkonnu or Crop Over. Caribbean Carnival’s origins lie in enslaved people mocking the luxurious excesses of their enslavers. It has evolved over time, maintaining social significance after abolition, through legacies of colonial violence and oppression, migration and independence movements. The actions of Carnival: masquerade, procession, making music, occupying space, are a means of affirmation. They celebrate life as a demonstration of collective resilience. In the UK Carnival asserts the centrality of Black life and Caribbean culture within Britain.

John Lyons Carnival J'ouvert 2001 Collection & © Painter and poet, John C. Lyons.

John Lyons Carnival Spectator 2007 Collection & © Painter and poet, John C. Lyons.

Alberta Whittle Celestial Meditations 2017 Collection & © Alberta Whittle

PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE

Most of the works in these final spaces were made in the last several years. They speak to the complex relationship between the past, present and future, a theme that recurs throughout the exhibition.

Stuart Hall, the Jamaican British cultural theorist, wrote that ‘detours through the past’ are necessary ‘to make ourselves anew’. These recent works, while speaking to the moment and context in which they were made, reflect on histories as productive sources of knowledge and inspiration.

This historical lens invites us to consider the changing and often contradictory relationship between Britain and the Caribbean. This history is one of both connection and separation. On the one hand, Caribbean culture has been assimilated into the mainstream. Music, food, literature and art with Caribbean roots are embedded within British culture and have changed British society. On the other, changes to immigration laws have severely limited immigration from the Caribbean, and hostile environment policies continue to impact communities across Britain.

The artists in this section explore these contradictions, building on the foundations laid by the generations who came before them. They embrace multidisciplinary practices and collaborative approaches, remaining committed to critiquing and overcoming the consequences of centuries of colonialism and discrimination. Through a combination of resilience, collectivism and creativity, they continue to produce cross-cultural spaces for Black British life to flourish.

Ada M. Patterson Looking for 'Looking for Langston' 2019, printed 2021 Collection and © Ada M. Patterson

Ada M. Patterson Looking for 'Looking for Langston' 2019, printed 2021 Collection and © Ada M. Patterson

Ada M. Patterson Looking for 'Looking for Langston' 2019, printed 2021 Collection and © Ada M. Patterson

AFTERWORD

Although several years in the making, this exhibition has an additional sense of urgency in the wake of protests in support of Black Lives Matter and the Windrush scandal. These events have forced a national reckoning with British history, challenging institutions to rethink the stories they tell and the communities they represent.

Britain’s history is profoundly intertwined with the Caribbean’s. Histories that may be very familiar to Caribbean-British people are insufficiently known in Britain generally. This gap in knowledge continues to have major social consequences for Caribbean-British communities in the UK.

Life Between Islands highlights some of these important histories across the past seventy years. However, as many of the exhibition artworks reveal, the story goes back much further. Much of Britain’s wealth and global power was built on the colonisation of the West Indies and the transatlantic slave trade. Tate’s founding benefactor, Henry Tate was a sugar refiner. He started his sugar business in 1859, some time after the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. Nevertheless, the industry from which he derived his wealth had been built on the labour of enslaved Africans and their descendants in the Caribbean, and subsequently relied on the indentured labour of Indian and Chinese people until the 1910s.

Many works in the exhibition are now part of Tate’s collection. However, like much of the mainstream British art world, Tate was late to recognise many of the artists included. Life Between Islands is part of a long-term commitment to diversify Tate Britain’s collection and exhibitions. It joins a number of major recent and forthcoming exhibitions and commissions by British artists of Caribbean heritage.