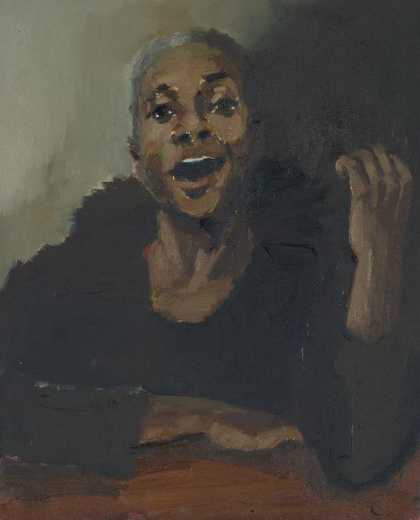

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

6pm Madeira 2011

© Tracey and Phillip Riese

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (born in London in 1977) makes figurative paintings drawn from a variety of source material. Her figures inhabit deliberately enigmatic settings that are timeless and often abstract. Working in oil paint on canvas or coarse linen, Yiadom-Boakye has developed a language of painting that is uniquely her own.

Fly In League With The Night is the first exhibition to celebrate Yiadom-Boakye’s work in depth. It spans work made at the Royal Academy Schools where she graduated in 2003 up to her recent paintings made in 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic. Yiadom-Boakye has been closely involved in the selection and arrangement of her work. The exhibition evolves according to the dynamics and conversations between paintings, without a strict chronology. ‘I wanted to think about a dialogue between the works, much the way I do when they’re in the studio, and also to consider the sequence or rhythm as you move through the galleries.’

The individual paintings do not have explanatory labels. Instead, you are invited to engage with Yiadom-Boakye’s works on their own terms. ‘There are so many things that I do or think about when painting that I can’t put into words. Any attempt at explanation can become, at best, superfluous. At worst, wholly inaccurate.’

Yiadom-Boakye is both a painter and a writer of prose and poetry. For her, the two forms of creativity are separate but intertwined. ‘I write about the things I can’t paint and paint the things I can’t write about,’ she has said. She refers to her paintings’ evocative titles as ‘an extra brush-mark’. They are integral to each work but are not an explanation or description.

At Ease As The Day Breaks Beside Its Erasure

And At Pains To Temper The Light

At Liberty Like The Owl When The Need Comes Knocking

To Fly In League With The Night.Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

Yiadom-Boakye initially learned to paint by working from life. But she changed her thinking and approach to painting at an early stage, while studying Falmouth School of Art, on the Cornish coast. She realised that she was less interested in making portraits of people and more in the act of painting itself, always at a slight remove from reality. ‘Being there, living away from London, in this quiet and beautiful place and with no particular expectations of what I should be doing. That was an education in itself. And a liberation of sorts.’

Painting itself is a language for Yiadom-Boakye, a powerful means of communicating beyond words. She begins with a colour, a composition, a gesture, or a particular direction of the light. Found images, memory, literature and the history of painting are all sources for her work. Each painting is a composite of different movements and poses, worked out on the surface of the canvas. The history of painting is important to Yiadom-Boakye, and her work asserts its ongoing potential for making meaning today.

I learned how to paint from looking at painting and I continue to learn from looking at painting. In that sense, history serves as a resource. But the bigger draw for me is the power that painting can wield across time.

I work from scrapbooks, I work from images I collect, I work from life a little bit, I seek out the imagery I need. I take photos. All of that is then composed on the canvas. [This lets me] really think through the painting, to allow these to be paintings in the most physical sense, and build a language that didn’t feel as if I was trying to take something out of life and translate it into painting, but that actually allowed the paint to do the talking.

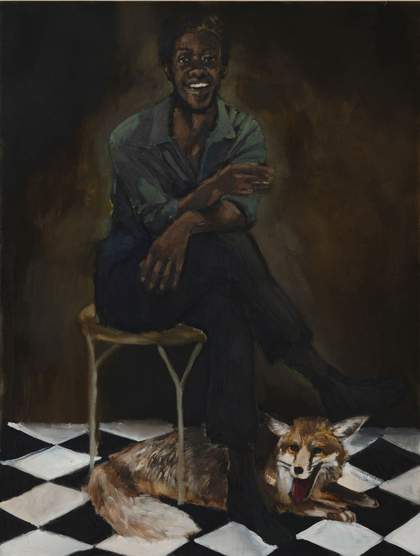

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

Penny For Them 2014

© Private Collection

Yiadom-Boakye’s fictitious figures inhabit private worlds. Though they might smile or glance in our direction, they are primarily concerned with their own business. They peer through binoculars at things that we can’t see, reflect on thoughts or have conversations, the subjects of which remain in Yiadom-Boakye’s invented realm.

The mood of each painting is crafted through careful attention to facial expressions, gestures and colour. Her evocative titles offer a hint of possible narratives. Each painted scene has a sense of a self-contained story, but one which may have another chapter for us to explore somewhere else in her body of work.

The paintings encourage us to wonder what an enigmatic smile could mean or what song the dancers might be moving to. If they are performing, it is not necessarily for us. There is a subtle resistance in the figures’ independence and introspection. Yiadom-Boakye has described her compositions as ‘... composites, ciphers, riddles. Of the world but only partially concerned with it. Concerned with the part that gives them life, less bothered by the rest.

Blackness has never been other to me. Therefore, I’ve never felt the need to explain its presence in the work any more than I’ve felt the need to explain my presence in the world, however often I’m asked. I’ve never liked being told who I am, how I should speak, what to think and how to think it. I’ve never needed telling. I get that from my family. Across generations, we’ve always known who we are. To be measured relative to something that actually has nothing to do with you or your experience, some self-appointed superior, the ghost of who you ought to be ... none of this has ever made any sense and yet somehow you live with it, live in it. But the idea of infinity, of a life and a world of infinite possibilities, where anything is possible for you, unconstrained by the nightmare fantasies of others, to have the presence of mind to walk as wildly as you will, that’s what I think about most, that is the direction I’ve always wanted to move in.

Following my own nose and doing as I damned well pleased always seemed to me to be the most radical thing I could do. It isn’t so much about placing black people in the canon as it is about saying that we’ve always been here, we’ve always existed, self-sufficient, outside of nightmares and imaginations, pre and post “discovery”, and in no way defined or limited by who sees us.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

Black Allegiance To The Cunning 2018

© Sheldon Inwentash and Lynn Factor

'My relationship to time is perhaps that of anyone who’s never felt particularly fixed anywhere.’

The figures in Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings have a timeless quality. They are deliberately difficult to place. She rarely includes anything that might allude to the style, fashion or culture of a specific period. There are very few shoes in her paintings, for instance. Few objects tie them to a particular era. In the domestic interiors too, architectural and design details are absent. Her figures are undefined by any surrounding context.

This uncertainty is important to the way Yiadom-Boakye works. The timeless quality she creates places particular demands on us: stirring our curiosity and imagination.