Restlessness

Probably the only thing one can really learn, the only technique to learn, is the capacity to be able to change.

Philip Guston

It's late at night. Philip Guston (1913-1980) is in the studio. He's not sleeping but he’s painting images of people who are. Legend shows the artist in bed, crowded by a nightmarish mix of objects. Punching fists, broken glass, a police baton, bricks, dirty cans, a startled horse. This scene captures the restlessness of an artist caught up in a world in turmoil.

This exhibition charts Guston’s 50-year career, his varying approaches to painting as well as his artistic, philosophical and social concerns. Living through much of the 20th century, Guston watched on and responded to wars, racial injustice, violence and political and social upheavals. These works raise questions about injustice and accountability. Throughout his life, he thought about the artist's responsibility to bear witness to what he called ‘the brutality of the world‘ and to challenge oneself creatively. Consistently changing and reinventing, he sought to make work that embodies life’s complexities, its beauty, absurdity, humour and suffering.

Struggle And Solidarity

I grew up politically in the thirties and I was actively involved in militant movements and so on, as a lot of artists were ... I think there was a sense of being part of a change, or possible change.

Philip Guston

Philip Guston’s birth name was Phillip Goldstein. Born in 1913, he was the youngest child of Jewish immigrants who had fled antisemitic persecution in present-day Ukraine. The family moved first to Montreal - Guston’s birthplace - before relocating to Los Angeles in 1922. They had little money and faced several tragedies. His father, who worked as a scrap collector, took his own life when Guston was still a child. His brother died a few years later after a car accident. He turned to art as a way of dealing with the impact of these traumas in his formative years.

Young Guston took an interest in drawing and cartooning, spending hours at the library poring over Italian Renaissance art books. His teenage friends, including artists Jackson Pollock and Reuben Kadish, shared his interest in modern art from Europe, particularly surrealism and the work of Pablo Picasso. His early paintings, such as Mother and Child, show him responding to this wide range of interests.

Guston began to engage with politics while he was still a teenager in LA. The 1930s was a time of growing anti-immigrant, antisemitic and racist beliefs in the United States, contributing to the rise of hate groups. Most notably, the Ku Klux Klan saw a resurgence in the 1920s and 1930s.

Guston and his friends were involved with socially-engaged art, creating large-scale, narrative-driven murals and paintings. They joined the Bloc of Painters formed under Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. Through their art this group aimed to support workers’ rights and protest against racial injustice in the US.

From The Wall To The Easel

I would like to think a picture is finished when it feels not new but old. As if its forms had lived a long time in you...It is the looker not the maker, who is so hungry for the new. The new can take care of itself.

Philip Guston

Guston began working as a muralist during the Great Depression of the 1930s. He was inspired by Italian Renaissance fresco paintings of the 1500s, seeking to channel their monumentality and iconography. In 1934, he and friends Reuben Kadish and Jules Langsner secured their first major mural commission, creating a massive fresco in Morelia, Mexico. Called The Struggle Against Terrorism, it shows people's resistance to persecution and violence from the medieval period through to the Ku Klux Klan in the US and the rise of Nazism across Europe.

After this, Guston produced one final mural in LA before relocating to New York in 1936. There he was joined by artist Musa McKim, who he married the following year. His work continued as a muralist through government-funded programmes. It was also when he changed his name to Philip Guston to mask his Jewish identity, as many others were doing at a time of growing antisemitism.

In the 1940s, Guston’s work transformed after he began teaching at universities in lowa City and Saint Louis. Working from a studio, he turned away from public art and muralism, focusing instead on easel painting and portraiture. He painted allegorical scenes, often of children playing and fighting. Affected by the trauma of the Second World War and the Holocaust, he turned to increasingly abstract compositions. As the figures broke apart, so did Guston’s practice, ‘everything seemed unsuccessful’, Guston said. ‘I couldn't continue figuration.’

The Struggle Against Terrorism

In 1934, Guston, Kadish and Langsner went to Mexico, where a revolutionary mural movement had been flourishing for more than a decade. Initiated after the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) and at first funded by the government, these murals retold stories of Mexican history on public walls and buildings. David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera, two of the most prominent artists associated with the movement, steered the trio to their first major commission: a gigantic wall in a historic building then run as a museum by the Universidad de San Nicolas in Morelia.

They produced a monumental and startling work, best known as The Struggle Against Terrorism. Its complex imagery presents a history of persecution with the image of a tortured woman at its centre. The mural also draws visual links between the hooded priests of the Spanish Inquisition and the Ku Klux Klan. At its completion in 1935, Time magazine wrote that the left half of the wall depicts nude workers knocking down ‘a colossal figure supposed to represent the Medieval Inquisition ... The other half of the wall is given over to the Modern Inquisition ... In the extreme upper right, Communists with sickle [and] hammer are rushing to the rescue.’ Left of the main wall on the upper floor, is a scene of lamentation. The artists signed their names beneath a surrealist-inspired scene of abduction on the ground floor. The mural’s criticism of the Roman Catholic Church and its depiction of nudity may have contributed to it being hidden from view in the early 1940s. Covered by a false wall until 1973, today it is preserved and maintained by the Museo Regional Michoacano, which is working with The Guston Foundation to conserve it.

Production by Fully Fledged Films, Director and Editor - Tessa Morgan, Director of Photography - Angel Jara Taboada, Line Producer (Mexico) - Maja Moguel, Production Driver - Alejandro Maltrana Lopez

Running time 4 min 26 sec

Special thanks to Museo Regional Michoacano, Dr Nicolas Leon Calderon, CULTURA / INAH and the Embassy of Mexico in the United Kingdom.

New Beginnings

I began to feel that I could really learn, investigate, by losing a lot of what I knew.

Philip Guston

In the late 1940s, Guston’s practice began shifting dramatically. He travelled to Europe for the first time in 1948 after he was awarded a fellowship at the American Academy in Rome. Confronting a creative crisis, he grew increasingly unsatisfied with figurative painting. He recalled, ‘The forms I wanted to make couldn't take the shapes of things and figures ... I felt torn ... between conflicting loyalties ... The loyalty to my own past, and the other loyalty of what you might still do.’ He did little painting and destroyed nearly all the works he made in Rome. A few small sketches survived the trip, including Drawing No. 2 (Ischia), documenting his continued journey towards abstraction.

After travelling across Europe and seeing art, Guston felt inspired to paint again. On returning to New York, Guston immersed himself in the growing scene of abstract painters. He became good friends with artists Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, the critic Harold Rosenberg as well as composers John Cage and Morton Feldman. In his paintings from this period, he tested himself by working intuitively in long bouts without stepping back from the canvas to analyse the composition. In 1957, he explained, ‘When I work, I am not concerned with making pictures, but only with the process of creation ... I feel that I have not invented so much as revealed, in a coded way, something that already existed.’

Conjuring Blue

Blue is a strange colour to use for me in any case - because it always evaporates ... But to bring it frontal, to make it feel on the plane, to me, is something to conjure with.

Philip Guston

Over the course of the 1950s, Guston’s reputation grew as an abstract painter known for his shimmering use of colour and expressive brushstrokes. He spoke about the challenges of creation, as well as the difficulty to deciding when a painting is finished. ‘The canvas is a court where the artist is prosecutor, defendant, jury, and judge ... You cannot settle out of court. You are faced with what seems like an impossibility - fixing an image which you can tolerate.’ Searching for ‘a more solid painting’, his works of the late 1950s contain larger blocks of colour that spread across the canvas.

New York in the 1950s and 1960s came alive with creativity. Musicians, visual artists, dancers and poets came together in a series of exchanges. Guston found the intellectual stimulation of these dialogues very productive, in particular with composer Morton Feldman. Both had a lasting impact on the other's creative practice.

Gaining increasing success, Guston was selected in 1960 to help represent the US at the Venice Biennale art exhibition. Two years later, the Guggenheim Museum in New York organised his first retrospective, helping secure his status as one of the leading abstract painters of his time.

Image Maker

I hope sometime to get to the point where I'll have the courage to paint my own face ... That's all a painter is, an image maker, is he not?

Philip Guston

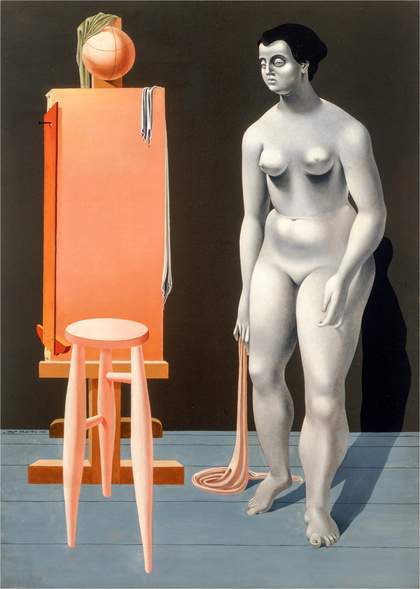

By the mid-1960s, Guston, restless and always challenging himself to evolve, entered a new phase. He drained most of the colour from his work, largely restricting himself to using black and white pigments. In these paintings, dark shapes, usually identified as heads, seem to emerge from grey backgrounds. He spoke about the miraculous feeling ot reaching a point ‘when the paint doesn’t feel like paint ... And you feel like you've just made a thing, like a living thing is there.’

Fighting with an impulse to paint figuratively, Guston described how he was ‘driven to scrape out the recognition’ of images in his works. ‘The trouble with recognizable art is that it excludes too much’, Guston explained in 1965. ‘I want my work to include more. And “more” also comprises one’s doubts about the object, plus the problem, the dilemma, of recognizing it.

By the time he exhibited these works at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1966, Guston was experiencing a major crisis in his creative life and his marriage with McKim. He gave up painting for around 18 months and eventually began to produce simple drawings. Some were abstract shapes or spare lines, yet others were of objects, often books. Torn between these two competing impulses, eventually he said, ‘the hell with it, I just wanted to draw solid stuff.’ The image maker within Guston had won.

What Kind of Man Am I?

The war [in Vietnam], what was happening to America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything - and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?

Philip Guston

Guston often grappled with the role art could play in the face of violence, racism and polarised political views in the US and across the world. While he had stopped making directly political art in the 1930s, he remained politically engaged. For instance, he served as co-chair for Artists for CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) in 1966. This group raised money for CORE, a civil rights organisation providing legal aid for activists, funding education and supporting Black voter registration.

In the late 1960s, like many around the country, Guston watched as a cataclysm of national and world events unfolded. In particular, the police violence against protestors at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago stood out to him. Such violence triggered Guston’s memories of the Ku Klux Klan, prompting him to make new images featuring hooded figures. That same year, also thinking back to the horrors of the Holocaust, he articulated his view of the artist’s responsibility to ‘unnumb’ oneself to the brutality of the world. He said, ‘that’s the only reason to be an artist ... to bear witness’.

Hoods

What if I had died? I'm in the history books. What would I paint if I came back? You know, you have to die for a rebirth.

Philip Guston

Guston’s desire to make narrative work to address the nightmarish injustices he saw in society led him to create large-scale paintings of hooded figures at the end of the 1960s. He saw them as symbols for evil, commenting that ‘my attempt was really not ... to do pictures of the KKK, as I had done earlier. The idea of evil fascinated me ... I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan. What would it be like to be evil? To plan and plot.’ The hooded figures can be seen driving around town, waiting at home or making art. By using cartoons’ capacity for satire, the paintings challenge projections of strength and intimidation, presenting these figures instead as ridiculous, yet unsettlingly commonplace.

Through this imagery, Guston raises questions about who is behind the hood and how their violent ideologies are masked in society. Refusing to offer direct explanation about the works, sometimes he spoke of them in relation to his own culpability saying, ‘I perceive myself behind the hood.’ The paintings also point to racist systems and institutions as well as society’s broader complicity in evil acts. He commented, ‘Well, it could be all of us. We're all hoods!’

In 1970, Guston revealed over 30 of these new paintings at a solo show at Marlborough Gallery, a commercial gallery in New York. The exhibition shocked critics and many of his closest friends who were dismayed with this new direction, particularly his change of style away from abstraction. The negative reviews were devastating, calling his work ‘crude’ and ‘out of touch’. Only a few friends and critics reacted positively. Art critic John Perrault for the Village Voice wrote, ‘It's as if De Chirico went to bed with a hangover and had a Krazy Kat [a cartoon character] dream about America falling apart ... It really took guts to make this shift this late in the game, because a lot of people are going to hate these things, these paintings. Not me!’

Painter's Form

There is nothing to do now, but paint my life; my dreams, surroundings, predicament desperation, Musa - love, need.

Philip Guston

Soon after the Marlborough show opening in 1970, Guston and McKim once again travelled to Italy tor several months. Depressed and deflated, he found relief in visiting the frescoes of his favourite artist Piero della Francesca and soon began a series of works on paper inspired by Rome’s gardens and ancient ruins. In these strange landscapes, hooded figures mingle with bricks and hedges, morphing into new forms like triangular pink trees. Living and working in Woodstock, New York for the rest of the decade, Guston remained out of the spotlight of the art world. It was the most productive period of his career, making hundreds of works each year full of his strange and uncanny imagery.

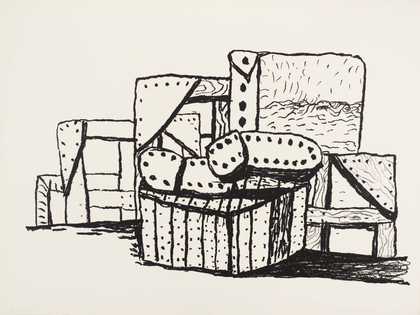

The everyday life of the painter, his memories as well as his personal hardships flooded his paintings. Painter's Forms shows a head vomiting out objects, or sucking them in - an unusual kind of self-portrait. Guston also began to represent himself as a wide-eyed cyclops in many of his paintings of the period. He depicted piles of objects, which he sometimes called ‘crapola’ or junk, in compositions that are dream-like and often have an offbeat humour. ‘I really only love strangeness, he wrote. ‘But here is another pileup of old shoes and rags, in a corner of a brick wall ... I've seen it before, but forgot.’

Poems And Pictures

Paul Valéry once said that a bad poem is one that vanishes into meaning.

Philip Guston

For Guston, the poetry of image-making was all about ambiguity and open-endedness, combining the familiar with the uncanny. He said, ‘My own demand is that I want to be surprised, baffled. To come in the studio the next morning and say, “Did I do that? Is it me? Isn't that strange!” In Guston’s personal iconography, objects seem to morph and rearrange. Piles of legs become a weighty monument, McKim’s forehead a sunrise. ‘I enjoy the feeling of the thing being caught at a very special certain moment ... like it just came into existence. And it's about to change into something else.’ Guston challenged himself to create compositions that in their completion retain a sense of flux, as if always in a state of transformation.

In the 1970s, Guston forged close friendships with a younger generation of poets including Clark Coolidge, Bill Berkson and William Corbett, as well as the writer Philip Roth. Guston said, ‘The few people who visit me are poets or writers, rather than painters, because | value their reactions.’ He created images for various poets and writers, making ‘poem-pictures’ incorporating verses alongside his characteristic assortments of everyday objects. This room contains several poem-pictures he made with McKim's poetry, often representing her in his works by her forehead and parted hair.

Night Studio

A painting feels lived-out to me, not painted ... So the paintings aren't pictures, but evidences - maybe documents, along the road you have not chosen, but are on nevertheless.

Philip Guston

Guston conjured up a world of lonely objects, bustling body parts, lively flames and sleeping figures. For years, he worked in the studio long into the night, painting and smoking. In the late 1970s, Guston and McKim struggled with health problems. McKim had a stroke in 1977 that kept her from writing poetry. Guston thought continually about his own mortality. Some of the paintings of these final years show colours emerging from thickly layered black paint. The imagery moves between nightmarish and comic.

A few weeks after the opening of his retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1980, Guston died aged 66 of a heart attack. This exhibition led to a renewed interest in his work, which has continued to grow ever since.

Throughout his career, Guston’s practice shifted as the world around him also changed. Often preoccupied with life's nightmares, he was also wrapped up in his artistic dreams. His paintings, where shapes and meanings are never fixed, continue to provoke, puzzle and inspire conversation. ‘A picture should tell stories’, he wrote. ‘It makes me want to paint. To see, in a painting, what one has always wanted to see, but hasn't, until now. For the first time!’