Robert Ryman

Guild (1982)

Tate

Sheena Wagstaff

Bob, I want to start in Philadelphia, to set the scene. It was serendipitous that you were included in an exhibition for which you did a special installation that coincided with Tate’s Newman exhibition, which began at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Robert Ryman

Yes. I did a painting at the Larry Becker Contemporary Art Gallery in Philadelphia, made up of eight or nine vinyl panels painted directly on the wall.

Sheena Wagstaff

You’ve previously told me that you met Barnett Newman. What was the occasion?

Robert Ryman

We did meet, and he came to the loft we had on 14th Street [in Manhattan]. We didn’t look at paintings … I don’t remember what we talked about; it was sort of …

Sheena Wagstaff

A social call?

Robert Ryman

Yeah. And then we went once to his apartment on Bowery and saw some early paintings that he had. I would have probably met with him again, but he died in …

Sheena Wagstaff

In 1970. So you must have been in your early twenties. He was about 25 years older than you. One of the remarkable things about Newman, which isn’t necessarily the case with other painters of his generation, is that he was clearly interested in the work of younger painters.

Robert Ryman

That’s right. He was very generous with his time to meet with others.

Sheena Wagstaff

I want to go back to when you first arrived in New York as a young saxophonist. Accounts of those early years tell of your discovering in the clubs of Manhattan a new kind of jazz. Barnett Newman too had a passion for music, in his early years – he wrote music reviews while he was studying philosophy at City College. It’s tempting to make an analogy between your appreciation of this new form of music and the radical new form of painting that both you and Newman respectively developed. Do you still listen to music while you’re painting?

Robert Ryman

It depends on what I’m doing.

Sheena Wagstaff

When you returned to New York in 1953 after the Korean War, you became a guard at the Museum of Modern Art. Actually, you were there for about seven years, your formative years as a painter. But am I right in saying that it wasn’t until the end of that period, the late 1950s, that you were aware of Newman’s work?

Robert Ryman

Yeah. At that time, I was just learning about painting, really, so I wasn’t really aware of what was going on. I was more involved with things like Cézanne and Matisse and Picasso. I didn’t really know any American painters.

Sheena Wagstaff

I’d love to come back to that point, along with a comment Newman made about what he considered to be American as opposed to European art. But first I’d like to prod your memory about the first landmark museum show – American Painting – which had four great Newman works, including Abraham 1949. The show ended its tour at the Museum of Modern Art in 1959. Were you around when that came to town?

Robert Ryman

I don’t really remember. But I remember seeing The Stations of the Cross 1958– 66.

Sheena Wagstaff

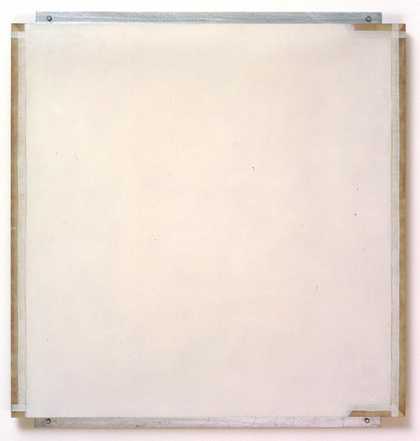

We talked some time ago about the equivalences – yet formal differences – between your work and Newman’s. One aspect is the shape of the canvas. You, more often than not, use squares. Newman – despite taking a few different shapes like the triangle for his paintings – primarily used the conventional rectangle.

Robert Ryman

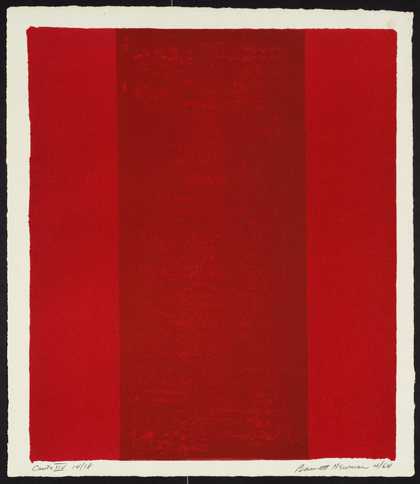

Mostly it was a traditional picture format of the rectangle. Newman came from the traditional painting of pictures, but his aesthetic – that was the main discovery – was different from traditional pictures in the sense that paintings move outward towards a person rather than their looking into it like a picture. The painting moved out of the wall and as a consequence you couldn’t put a frame or anything on the edges because that would stifle it. These were not pictures in the traditional sense, and that was Newman’s real discovery in the aesthetic. Mark Rothko (1903–1970) did the same.

They worked with the environment of wherever they were in the room. And that’s why they couldn’t be hung like traditional pictures. In my opinion, they shouldn’t be hung close to each other. There should be a fair amount of space so they can breathe, so to speak. So we can feel them.

Sheena Wagstaff

What did you think of the way they were hung in Philadelphia?

Robert Ryman

Very good. It was interesting to see some of the very early paintings that I’m not so familiar with; in many cases they are similar to some of Rothko’s early paintings. And there’s also something that was unfortunate with a painting called Black Fire I 1961, which has a very strong black vertical. Someone – I guess it was the collector – had put black tape down the right side, so when viewing the painting from the right you see another black vertical, which shouldn’t be there. There were quite a few things like that. The aesthetic is such a definite and sensitive situation you really can’t add or change certain things.

Sheena Wagstaff

One source of a misunderstanding of the complexity of Newman’s work is a quote from The Tiger’s Eye, which in 1948 published Newman’s essay The Sublime is Now. There has been much discussion about what he actually meant. Newman wrote, ‘I believe that here in America, some of us, free from the weight of European culture, are finding the answer, by completely denying that art has any concern with the problem of beauty and where to find it.’

Robert Ryman

A lot was made of this that I think shouldn’t have been. I think what he meant by the sublime was that a painting is a miracle, in a sense. We can talk about technical aspects of painting, the brushes, the paints, the mixing, how things go together and so on, but when it comes to talking about how the painting happened, we don’ t have the words for it, because it’s a miraculous thing. That’s what he meant by sublime, that painting is a mysterious experience.

Sheena Wagstaff

Is this a mysterious experience which goes beyond the physical and aesthetic experience, into the mystical for instance? Is it transcendent?

Robert Ryman

Well, no, it’s not a mystical thing, it’s just a feeling of delight, I guess, and a feeling of rightness … it’s something you haven’t seen before. You don’t know how it happened.

Sheena Wagstaff

Newman could also have been referring to a European or traditional significance that beauty had in the 1940s, which has a different resonance today. But I feel that instead it was more to do with being liberated from a European legacy to make something that is a purely American form of expression.

Robert Ryman

Maybe he was talking about picture-making or storytelling. It might have been storytelling. I mean, if a painting was about a landscape, a cityscape or a person, a situation, political maybe, it was usually about something ‘important’. But this is different. It’s not about anything. Maybe that’s what he was talking about. It was a kind of a beauty that he was not involved with.

Sheena Wagstaff

What do you think of something that the Harvard Professor Yves Alain Bois wrote recently about Newman: ‘I have become convinced that Newman, uniquely in the 20th century, conceived of his pictorial oeuvre as a deck of cards, in which every work has a particular function, and the specific role each plays varies according to the changing context. As his total work increases, so do the number of connections between paintings. Newman is almost alone as a painter in insisting on maintaining this web of internal correspondences.’ He’s talking about the interconnectedness of each work to the one before and the one after. And perhaps he’s proposing that the total work adds up to more than the sum of its parts.

Robert Ryman

Well, I think that’s true with all painting, in a sense. That has to do with the architectural aesthetic of the paintings. When you see a retrospective, you see many of the paintings together, which normally you don’t. Of course, in between every painting that we see, there are paint-ings that we don’t see, because he did many others, even paintings that were quite different between one painting and another painting which we think came right after the first one that we see, but that’s never the case. There were always other paintings. And other drawings, and some of those could be quite different. But within the whole work of the painter, there is this sensibility the painter has that is always the same, a certain approach that he takes. That’s always there.

Sheena Wagstaff

So, given an artist’s consistency of approach to his work, I’d like to take up your point about Newman’s paintings coming out to the viewer, and not acting as windows. I wonder whether you think that a viewer moving from one to the next painting experiences different kinds of responses to the work as she moves through the space of each gallery. I mean that there is more at stake than just the viewer confronting the painting and being enfolded by it. Rather she holds the experience of the previous painting just as she embraces the next one. Do you think that there are gradations of response from the viewer, moving through an exhibition?

Robert Ryman

Well, yes, I think, always. As you go from one room to the next, everything should be a surprise.

About the artist

Robert Ryman was born in 1930 in Nashville, Tennessee, where he studied music at George Peabody College for Teachers. Following service in the Korean War, he moved to New York in 1952 as a jazz saxophonist, and worked as a guard at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). He first exhibited at a MoMA staff show in 1958 and began painting full-time in the early 1960s, when he became associated with such New York artists as Eva Hesse, Sol LeWitt and Sylvia and Robert Mangold. Around this time, he started painting on metal, mainly aluminium, mostly in white. By the end of the decade, Ryman had exhibited at the Guggenheim Museum with artists including Ellsworth Kelly, Jackson Pollock and Frank Stella. In the past 30 years he has had solo exhibitions at major international museums including Tate in London, MoMA and the Guggenheim in New York, and Muse d’art moderne de la ville de Paris. He lives and works in New York.

This article was originally published in Tate Magazine issue 1.