Although a number of twentieth-century exhibitions are already hailed as ‘landmark exhibitions’, one major and highly innovative exhibition has eluded the attention of scholars until recently: Les Immatériaux, co-curated in 1985 for the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris by the philosopher Jean-François Lyotard and the design historian and theorist Thierry Chaput.1

Among its many novel features was the fact that it was the first exhibition in which a philosopher played a leading role, opening the door to many other instances where intellectuals would become ad hoc curators.2 Instead of the standard sequence of white cubes, Lyotard and Chaput divided the entire fifth floor of the museum with large sheets of uncoloured metal mesh hanging from the ceiling. Contrary to the neutral lighting of most exhibition environments, Les Immatériaux offered a theatrical setting – the work of young stage designer Françoise Michel – which played with stark contrasts between spotlit exhibits and areas of near total darkness.3 In Chaput’s words: ‘Decked in demanding grey, illuminated by improbable lighting, with unpredictable ideas allowed to hover, this hour, this day in this year, suspended, rigorously ordered yet without system, “The Immaterials” exhibit themselves between seeing, feeling and hearing.’4

Importantly, Les Immatériaux brought together a striking variety of objects, ranging from the latest industrial robots and personal computers, to holograms, interactive sound installations, and 3D cinema, along with paintings, photographs and sculptures (the latter ranging from an Ancient Egyptian low-relief to works by Dan Graham, Joseph Kosuth and Giovanni Anselmo). One reason for the heterogeneity of objects represented in Les Immatériaux was that many of the exhibits were chosen by Chaput well before Lyotard was invited to join the project in 1983.5 Indeed, the Centre de Création Industrielle (CCI) – the more ‘sociological’ entity devoted to architecture and design within the Centre Pompidou, which initiated Les Immatériaux – had been planning an exhibition on new industrial materials since at least 1982.6 Variously titled Création et matériaux nouveaux, Matériau et création, Matériaux nouveaux et création, and, in its last form, La Matière dans tous ses états, this exhibition, first scheduled to take place in 1984, already contained many of the innovative features that found their way into Les Immatériaux.7

These features included an emphasis on language as matter, the immateriality of advanced technological materials (from textiles to plastics and holography), exhibits devoted to recent technological developments in food, architecture, music and video, and, crucially, an experimental catalogue produced solely by computer in (almost) real time. The earlier versions of the exhibition also involved many of the future protagonists of Les Immatériaux, such as Jean-Louis Boissier (among several other faculty members of Université Paris VIII, where Lyotard was teaching at the time) and Eve Ritscher (a London-based consultant on holography). Furthermore, Les Immatériaux benefited from projects pursued concurrently by other groups within the Pompidou which joined Lyotard’s and Chaput’s project when it was discovered that their themes overlapped. Thus, an exhibition project on music videos initiated by the Musée national d’art moderne was incorporated into Les Immatériaux, and another project on electro-acoustic music developed by Ircam (Institut de Recherche et de Coordination Acoustique/Musique) also seems to have merged with the 1985 exhibition.8

Although other institutions expressed interest in taking the show, Les Immatériaux was too much a reflection of the unusual museographic practices of the place where it originated to translate into different contexts, and the show did not tour.9 For Les Immatériaux was much more than an ‘exhibition’, simply understood. It drew upon all the entities within the Centre Pompidou, offering musical performances (including the world premiere of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Kathinkas Gesang), an impressive film programme (titled ‘Ciné-Immatériaux’, curated by Claudine Eizykman and Guy Fihman), a three-day seminar on the relationship between architecture, science and philosophy, as well as three related publications, in addition to the two catalogues.10 Les Immatériaux would in fact be among the last exhibitions at the Centre Pompidou to embody the latter’s original ambition to be a centre open to all forms of expression, from industrial design and urbanism to painting and performance, instead of a modernist museum based on the neat differentiation between departments according to media.11 Les Immatériaux represented, as it were, a hinge in the Centre Pompidou’s history, between a more conventional future (the CCI effectively dissolved a few years later, merging with the Musée national d’art moderne) and a certain postmodern idealism that tolerated, even encouraged, the blurring of disciplines and exhibitions with an element of pathos and drama.12 As Chaput expressed it in 1985, Les Immatériaux represented ‘one of the last “romantic” experiences.’13

As the originator of the exhibition, and its main representative within the Centre Pompidou, Chaput played a key role, though he was understandably the less visible of the two co-curators vis-à-vis the public and especially the media.14 Bernard Blistène was responsible for the selection of most art works in Les Immatériaux. Most but not all: the Egyptian low-relief was Lyotard’s personal choice, and we can assume that Lyotard was responsible for the inclusion of Marcel Duchamp, Daniel Buren and Jacques Monory, since he had written extensively on the three artists prior to his involvement in Les Immatériaux.15

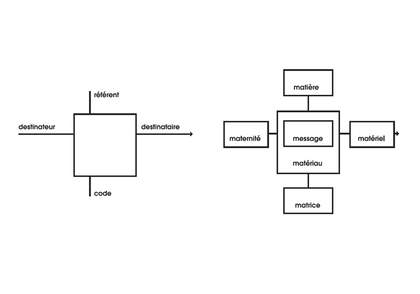

As for Lyotard himself, he was instrumental not only in securing certain loans and the participation of prominent figures in the exhibition catalogues, but also in designing the exhibition’s overarching linguistic structure. As early as spring 1984, Lyotard had suggested the conflation between five French words deriving from the Indo-European root ‘mât’ (to make by hand, to measure, to build) and the communication model first developed by Harold Lasswell – ‘Who / Says What / In Which Channel / To Whom / With What Effects?’ – later translated into a communication diagram by Claude Shannon and Norbert Wiener, which Roman Jakobson would apply to, and amend in light of, linguistics. Lyotard’s conflation of these communication models with the etymological group of mat- terms was hardly rigorous.16 What it proposed, however, was an epistemological short-circuit between heterogeneous discourses, the one poetic, the other scientific, to establish the following equivalences: matériau = support (medium), matériel =destinataire (to whom the message is addressed), maternité = destinateur (the message’s emitter), matière = référent (the referent), and matrice = code (the code) (fig.1).

Fig.1

Communication diagram (Petit Journal, 28 March–15 July 1985, Paris, p.2)

Diagram adapted by Sara De Bondt

The drawings collected in the Album section of the exhibition catalogue indicate that the layout of Les Immatériaux had reached a near-definitive stage by September 1984. Once past the initial corridor, the visitor would have to choose between one of five strands (or ‘valences’) leading through the exhibition, each corresponding to one of the five mat- strands. Each mat- strand in turn would incorporate a number of ‘zones’, with each ‘zone’ unified by a common soundtrack, audible through headphones distributed to each visitor before entering the exhibition.17 (The soundtrack, selected by Lyotard’s then collaborator and future partner Dolorès Rogozinski, and engineered by the Pompidou technician Gérard Chiron, consisted of excerpts of literary and philosophical texts by the likes of Maurice Blanchot and Samuel Beckett.)

Each ‘zone’ subdivided into several ‘sites’, that is, variously sized installations with more or less obvious reference to the mat- strand in which they were included. For example, the ‘Nu vain’ site designed by Martine Moinot – an active figure in Lyotard’s support team at the Centre Pompidou – featured ‘twelve asexual mannequins’ with, at the back, ‘a screening of a passage from Joseph Losey’s film Monsieur Klein alternating with a photo from a concentration camp prisoner.’18 As the visitor entered this site – one of three in the first ‘zone’ in the ‘matériau’ mat- strand – she or he would have heard the voice of the poet and playwright Antonin Artaud (‘Pour en fini avec le jugement de Dieu’, originally intended to be broadcast on radio in 1948) and Rogozinski (‘The Angel’). Thus guided – or, more accurately, misguided – through the exhibition’s obscurity by the soundtrack, the isolated visitor of Les Immatériaux would drift from site to site and strand to strand with, as only markers, the switch between voices indicating the passage from one zone to another.

If no two trajectories through Les Immatériaux could possibly be alike – given the freedom the visitor had to choose her or his own sequence of ‘sites’ and ‘zones’ – Lyotard and Chaput were careful to document the visitors’ drifting patterns, devising a dense network of self-indexing nodes both inside and outside of the exhibition. Each visitor to Les Immatériaux was to receive a magnetic card with which to record the ‘sites’ she or he went through: upon leaving the exhibition, she or he should have been able to print a hard-copy record of the visit, though this system of ‘mise en carte’ does not seem to have been implemented.19 Another self-indexing node in Les Immatériaux, ‘Les Variables Cachées’ in ‘zone’ 12 (‘matrice’ strand) allowed visitors, by way of a computer terminal, to provide answers to a set of questions, which contributed to statistical views of the exhibition’s public projected on a screen in the same ‘site’.20 Published in 1986, the exhaustive study of Les Immatériaux by the sociologist Nathalie Heinich constituted another means of measuring and archiving the visitors’ movements through, and reactions to, the exhibition.21

The idea of constituting an archive of the communication generated by Les Immatériaux, mediated analogically as well as digitally, also determined the exhibition’s catalogues. Instead of the traditional single volume acting as an anticipated record of the completed event, two publications were issued, both of which reflected the process underpinning Les Immatériaux. The first is a folder with, on one side, ‘L’Inventaire’ – a sheaf of loose pages each describing one of the exhibition’s sixty-one ‘sites’ – and, on the other, a bound ‘Album’ of notes and sketches (most of these by Philippe Délis, the scenographer of Les Immatériaux) documenting the exhibition’s development from La Matière dans tous ses états in 1984 to a snapshot of the installation, presumably taken in early 1985. The second publication, titled ‘Epreuves d’écriture’, is a soft-cover bound volume containing the records of a computer-mediated discussion among twenty-six participants – including Daniel Buren, Michel Butor, Jacques Derrida and Isabelle Stengers – of a set of fifty terms proposed by Lyotard.22 Lyotard held this second volume in high esteem: ‘It is probably a “book” that elicits a kind of beauty, as it were, very different from what I was accustomed to. For me it is a great book.’23 (fig.2)

Fig.2

Les Immatériaux exhibition catalogues (left: Album and Inventaire; right: Épreuves d’écriture) 1985

© Tate

The postmodern

With its self-reflexivity and auto-archiving impulse, Les Immatériaux could be considered a self-remembering exhibition – to paraphrase exhibition historian Reesa Greenberg – on the condition that we recognise this remembering as paradoxical and essentially Duchampian.24 For, to refer once again to the metaphor of the hinge, Les Immatériaux seemed to pivot, undecided, between a ‘sensibility’ looking backwards, so to speak, to an origin that never was – embodied by the Egyptian low-relief sculpture and the pseudo-etymology of the exhibition’s title – as well as beyond, to a techno-scientific future always almost-here, that is, to a postmodernism always in need of experimentation and hence infinitely deferred. In his writings on the postmodern, Lyotard would often qualify this wavering as an ‘anamnesis’, a psychoanalytic working through in the future anterior, ‘in order to formulate the rules of what will have been done.’25 What Duchamp scholar Thierry de Duve writes of the feeling elicited by the appearance of Duchamp’s readymade could well apply to Les Immatériaux: ‘the paradoxical sense of the future that a deliberatively retrospective gaze opens up.’26 In fact, Lyotard was explicit in placing Les Immatériaux under the sign of Duchamp. A ‘site’ in ‘zone’ 6 (in the ‘matériau’ or ‘medium’ strand) was named ‘Infra-mince’ and featured various handwritten notes and sketches by Duchamp related to the latter’s notion of ‘infra-thin’, as well as an excerpt of Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past on the soundtrack. In ‘zone’ 20 (‘matière’ or ‘referent’ strand), a ‘site’ entitled ‘Odeur peinte’ (painted odour) included two works by Duchamp, the 1959 Torture-Morte and Belle haleine, Eau de voilette from 1921, accompanied by a reading of a text by cultural theorist and curator Paul Virilio. Duchamp, in other words, could be said to play the role of yet another dubious postmodern ‘origin’, after the mat- etymology and the Egyptian sculpture, both for the Centre Pompidou and for Lyotard. Indeed, Lyotard’s first contact with the Pompidou took place in 1977, when he contributed to the catalogue of its inaugural exhibition, devoted to Duchamp.27

It is perhaps a symptom of the transformation of the postmodern from a term of historical classification into a more allegorical principle, and of an increasing awareness of the value of exhibitions as performative sites for historical reflection, that Les Immatériaux is now, after more than two decades, entering philosophical and art-historical discourses. But the main cause for the longstanding exclusion of Les Immatériaux from these discourses was undoubtedly Lyotard’s own reticence to discuss his 1985 curatorial project. Shortly after his collaboration with the Pompidou came to an end, Lyotard wrote of ‘looking forward to not having to think about (to suffer from)’ Les Immatériaux again. He went on to describe his curatorial experience as having prompted an ‘anamnesis’, and the exhibition itself as having ‘mastered us much more than we mastered it.’28

Why would Lyotard have judged his work on the exhibition in such traumatic terms as ‘suffering’ and ‘mastery’? The fact that the public and critical response to Les Immatériaux was mostly negative may have been a factor.29 ‘Decked in demanding grey’, the exhibition was unlikely ever to have enjoyed widespread popular appeal, but the ‘feeling of a period coming to an end and the worried curiosity that awakens at the dawn of postmodernity’ – which the curators sought to evoke – was no doubt accentuated, albeit unintentionally, by the numerous technical failures that plagued Les Immatériaux.30 The headsets, a prototype then being tested by Philips, were particularly prone to breaking down, forcing the exhibition at one point to stay open only part-time (fig.3).31 The headsets were required, not optional, and came at a fee, which provoked the ire of those wanting to see the exhibition without its soundtrack.32 One letter addressed by a visitor to the Pompidou complained that the exhibition discriminated against the hearing-impaired.33 Another particularly scathing critique, by Michel Cournot and published in Le Monde, took the exhibition to task for assaulting the visitor with incomprehensible stimuli, from the magazine handed out before entering – impossible to read in the darkened exhibition space – to the unidentified voices streaming through the headsets.34

Fig.3

Philips headset used in Les Immatériaux 1985

© Gérard Chiron

Lyotard’s rebuke to Cournot’s criticism, which also appeared in Le Monde, defended the exhibition’s technological letdowns, arguing that such is the price to pay for experimentation: ‘Mr Cournot wanted to revel in the jubilation offered by the new mastery promised by the “technologists”, by the prophets of a “postmodern” break? The exhibition denies it, and this is precisely its gambit, to not offer any reassurance, especially and above all by prophesising a new dawn. To make us look at what is “déjà vu”, as Duchamp did with the ready-mades, and to make us unlearn what is “familiar” to us: these are instead the exhibition’s concerns.’ Lyotard went on to write: ‘The idea of progress bequeathed by, among others, the Enlightenment has faltered, and with it a triumphant humanism. Greatness of thought – Adorno’s for example (must I spell his name out?) – is to endure the fright derived from such a withdrawal of meaning, to bear witness to it, to attempt its anamnesis.’35

Beyond its negative reception, I suggest that Les Immatériaux proved a particularly difficult experience for Lyotard because it represented a failed attempt at recasting ‘the postmodern’, an expression which his book La Condition postmoderne, first published in 1979, helped transform into one of the more widely circulated theoretical catch-phrases of 1980s. When asked why he was invited to become chief curator of Les Immatériaux, Lyotard consistently professed to have no clue.36 Yet the slim 1979 volume, whose influence extended to both sides of the Atlantic, must have played a major role in Lyotard’s selection to lead the exhibition project devoted to ‘new materials’.

Of course, as Lyotard was the first to acknowledge, the problem was that La Condition postmoderne could not assume the responsibility of having the final say on ‘postmodernism’, given the context of its writing – a commission by the state of Quebec for ‘a report on knowledge’.37 As Lyotard scholar Niels Brügge has remarked, if the renown of La Condition postmoderne weighed so heavily on the philosopher’s subsequent writing, it is because the book itself is ambivalent, describing the postmodern at once as modal and epochal – that is, as a narrative framework in which certain functions come to the fore (such as performativity and paralogy in language games), and as an historical moment marking the decline of legitimating narratives (for example, of emancipation and enlightenment).38

After noting the absence of the postmodern in Le Différend – the book published in 1983 which Lyotard was finishing when he embarked on Les Immatériaux – Brügge writes that the ‘postmodern continued to haunt Lyotard’s work’.39 Brügge refers to an essay entitled ‘Note sur les sens de “post-”’, in which Lyotard states that ‘understood in this way, the “post-” of “postmodern” does not mean a movement of come back, of flash back, of feed back, that is of repetition, but an “ana-” process, an analytical process, a process of anamnesis, of anagogy and anamorphosis, which works through [élabore] an “initial forgetting”.’ In this essay, Lyotard cites painting as a prime example of postmodern anamnesis:

I mean that to properly understand the work of modern painters, say from Manet to Duchamp or Barnett Newman, one should compare their work to an anamnesis in the analytic sense. Just as the analysand tries to work through [élaborer] her or his current problem by freely associating apparently inconsistent elements with past situations, allowing her or him to uncover hidden meanings in her/his life and behavior, so we can understand the work of Cézanne, Picasso, Delaunay, Kandinsky, Klee, Mondrian, Malevich and finally Duchamp as a ‘perlaboration’ (durcharbeiten) undertaken by modernity on its own meaning.40

Les Immatériaux offered Lyotard the opportunity to work through the haunting of La Condition postmoderne, the former providing him with a stage upon which to perform the transition from an epochal or modal postmodern into an allegorical or anamnesic one. Whereas La Condition postmoderne was subtitled ‘Report on Knowledge’, one of the subtitles suggested by Lyotard forLes Immatériaux was ‘L’Esprit du temps’, which, to use the more common German expression, translates as Zietgeist.41 By suggesting this subtitle, Lyotard would have been making a clear attempt to reclaim the postmodern from the version of the term made fashionable by such exhibitions as the 1982 Zeitgeist, which sought to include the latest expressionist forms of painting in a twentieth-century avant-garde tradition.42 In a 1985 interview with Blistène, Lyotard accuses the supporters of a ‘return to painting’ of forgetting ‘everything that people have been trying to do for over a century: they’ve lost all sense of what’s fundamentally at stake in painting. There’s a vague return to a concern with the enjoyment experienced by the viewer, they’ve abandoned the task of the artist as it might have been perceived by a Cézanne, a Duchamp.’43

Lyotard’s own version of a postmodern Zeitgeist at the Centre Pompidou was an affective hovering between the ‘post’ he had imprudently prognosticated in 1979 and a lost modernism that could never again be brought back to life. This paradoxical temporal stasis would provide the clearest sign, not of the decline of the twentieth-century avant-garde as such, but of the end of the possibility of recuperating it to justify an increasingly complex and progressively dehumanised techno-scientific environment. For Lyotard, the historical break in the telling of twentieth-century history is marked – as it was for many before him, particularly Adorno – by the mass murder of the Jews during the Second World War:

Following Theodor Adorno, I have used the term ‘Auschwitz’ to indicate the extent to which the stuff [matière] of recent Western history appears inconsistent in light of the ‘modern’ project of emancipating humanity. What kind of reflection is capable of ‘lifting’, in the sense of aufheben, ‘Auschwitz’ by placing it in a general, empirical and even speculative process directed towards universal emancipation? There is a kind of sorrow [chagrin] in the Zeitgeist, which can express itself through reactive, even reactionary attitudes, or through utopias, but not through an orientation that would positively open a new perspective.44

Anamnesis

It is striking to what point this element of ‘chagrin’ – ‘sorrow’ in English – particularly in its relation to ‘Auschwitz’, is overlooked in the (still scant) literature on Les Immatériaux.45 This is all the more remarkable since the word carries, at least in France, inescapable connotations of stalled remembrance of World War Two, after Marcel Ophüls’s well-known documentary from 1969 Le Chagrin et la pitié (The Sorrow and the Pity), a film that gives equal time to testimonies from former French resistants and collaborators.

Le Différend – which, as I mentioned, Lyotard was completing when he was approached by the CCI to curate the exhibition – opens with the prediction that in the next century ‘there will no longer be any books’, since there will be no time to read and the aim of all communication will be to absorb ‘messages’ as efficiently as possible. Thus, like all books published at the end of the twentieth century, Le Différend stands at the end of the line (‘appartient … à une fin de série’).46 To oppose, or at least defer this dystopian outcome, Lyotard theorises ‘the differend’, the irresolvable difference between heterogeneous regimes of phrases. ‘The differend’ never allows one to conclude, as it takes the interrogative form of Arrive-t-il? (‘Will it occur?’ or ‘Is it coming?’), a temporal indecision Lyotard extends to ‘Auschwitz’, an event he takes not only as an historical break (as Adorno did, according to Lyotard), but as a linguistic one (hence the use of quotation marks).47 As an exhibition and not a book, and as a dramaturgy beginning with images referencing the Shoah (through Losey’s ‘fictional’ cinematic account), Les Immatériaux staged an experience of ‘sorrow’ meant to give rise to a profoundly negative feeling – a feeling the visitor could not possibly have escaped as she or he wandered through the dark maze of the Centre Pompidou, confronted by the endless choices to determine a trajectory without any identifiable goal in sight. As Lyotard put it, ‘The exhibition will have to take into consideration this aspect of sorrow [chagrin] and this form of ‘continuation’ [poursuite] of techno-scientific development, this extraordinary responsibility of a hundred years of contemporary or avant-garde art where all the big questions were posed (…) There needs to be this aspect of sorrow and this aspect of jubilation through productive questioning.’48

In Les Immatériaux this jubilation never arrives – as Lyotard reminded Cournot in their heated exchange in Le Monde. Contaminated by doubt instilled from the ‘pessimistic’ beginning of the exhibition, the visitor to Les Immatériaux could never be certain that what should occur had, in fact, occurred, whether jubilatory or not. ‘When you are near the end of the exhibition maybe there is a sort of optimism but my idea and that of the organising team was not to be optimistic or pessimistic: the exhibition is neutral ground’, Lyotard commented.49 Note the ‘maybe’, for it suggests a fundamental hesitation, a circularity and endlessness that can be termed ‘neutral’ but that can just as easily be understood as Lyotard’s indecision that after ‘Auschwitz’ – that is, after coming to terms with the technosciences not as the enemy of art (as per the Frankfurt School) but as complicit in an increasing complexification of interaction at every level of human life – something might, indeed, occur.50

As the visitor entered Les Immatériaux, she or he encountered the Ancient Egyptian low-relief, depicting a goddess offering the sign of life to the kind Nectanebo II. Looking at this sculpture – ‘irreplaceable witness for us of what “we” are in the process of finally losing’, as Lyotard wrote – in the exhibition’s antechamber, the visitor would have heard, through the headset, the sound of human breathing.51 The visitor then proceeded through a long dark corridor, at the end of which stood a large-scale mirror, and which lead to a circular open-plan space entitled ‘Théâtre du non-corps’(‘Theatre of the non-body’), where she or he faced five boxes, one per mat- strand coursing through the exhibition. Each box contained a miniature theatre set inspired by Beckett’s plays, designed by Beckett’s stage designer Jean-Claude Fall and by Gérard Didier. Antonia Wunderlich, in her important monographic study of Les Immatériaux, has convincingly argued that the sequence formed by the Egyptian low-relief, the dark corridor, the mirror and the circular amphitheatre-like space with the five miniature theatre sets would have suggested to the visitor that the origin of the exhibition lay in the disembodied, objective and self-reflexive gaze of modernity.52 For Lyotard, it is this gaze that allowed the goddess’ sign of life to be measured ‘like cattle’ by the Nazi doctor pictured in the fragment of Losey’s film projected in the ‘Nu vain’ ‘site’, and that the entire exhibition attempted to re-stage in light – a threatening, uncertain light – of technoscientific postmodernity.53 At the other end of Les Immatériaux, the visitor once again encountered the same Egyptian low-relief, this time presented as an image cut up into vertical strips projected onto a screen, as if to intimate that the mythical image would have to be thoroughly transformed, spliced and reassembled before ‘we’ can begin to re-imagine another founding gesture, another community.

It is tempting to assimilate this final blurred projection of a supposed common cultural heritage to a sublimation of modernity into postmodernity, or to a form of transcendence. Lyotard has stated that the sublime was very much on his mind while working on Les Immatériaux, particularly as he was lecturing on ‘the question of the sublime’ at the Université Paris VIII at the time, and publishing widely on the subject.54 But while he was preoccupied by the sublime, and would remain so long after Les Immatériaux, his declared area of research in 1984 was ‘Philosophy and the new media [‘les nouveaux supports’] – postmodernity.’55 One could argue that Lyotard sought with Les Immatériaux to disassociate the postmodern from the sublime, if only by excluding those art works he had previously qualified as sublime, such as Barnett Newman’s paintings, and by making multiple references to Duchamp, whose aesthetic, Lyotard pointed out, ‘has nothing to do with the sublime’.56 Rather than simply produce an aesthetic experience illustrative of a sublime or techno-scientific future, the blur performed by Les Immatériaux might then allude to the space of Masaccio’s frescoes and Cézanne’s late paintings of the Sainte-Victoire mountain, in which Lyotard recognised the deconstruction of representation in order to intimate a sense of the inevitable decline that accompanies the exhaustion of modernity’s claim to pure, total and objective reason. As Lyotard wrote already in 1971, ‘This space [of Cézanne’s late paintings] is no longer representational at all. Instead, it embodies the deconstruction of the focal zone through the curved peripheral plane of the field of vision. It does not grant an “over there” to be contemplated according to geometrical optics, but manifests the Sainte-Victoire mountain in the process of becoming visible.’57

In short, the space embodied at Les Immatériaux is a dynamic one, itself based on a pictorial one, a temporal experiment that makes manifest, at one remove, the spatial experiment of the painter making manifest the object of her/his gaze in the process of becoming visible. In the documents Lyotard and Chaput prepared for the press, they defined Les Immatériaux not as an exhibition but as a ‘mise en espace-temps’, a ‘non-exhibition’, a ‘manifestation’. By foregrounding this last expression, the two curators sought to ‘question the traditional presentation of exhibitions, which are indebted to the salons of the eighteenth century and to galeries’.58

‘Painting’

For Lyotard, one of the most successful ‘postmodern’ efforts to translate the spatial experience of the exhibition into the temporal experience of a manifestation was the philosopher and critic Denis Diderot’s reports on the Paris Salons of the 1760s, which relied on narrative devices that played upon – or deconstructed to endlessly reconstruct – painting’s power to elicit the sublime.

In Diderot’s report on the Salon of 1767, from which Lyotard quotes in the preparatory documents for Les Immatériaux, the eighteenth-century critic imagines himself wandering through a landscape modelled after a painting by Joseph Vernet, in the company of a fictitious character (a priest) who claims that painting could never possibly reproduce the sublime beauty of the landscape – which is, of course, based precisely on a Vernet painting. In this intermingling of art and life, of realism and fiction, Lyotard sees Diderot performing ‘a kind of rotation’ whereby the author ‘settles in a fictitious space represented by painting and from there defies all possible painting’.59 This is how the sublime could be said to re-enter Les Immatériaux, by way of a derivation from the illustration of the sublime (in the works of Newman, for example) to a non-representational, second-degree sublime that comes to the fore in the act of manifesting, or trying to manifest the sublime at work in painting.60

As opposed to the Enlightenment Bildungsroman and the modern city though which the Baudelairian flâneur or Situationist chronicler recorded his first-person impressions, Les Immatériaux refused to grant primacy to the subject’s all-powerful subjective eye. Had it aspired to showcase the sublime, Les Immatériaux would have taken the form of the ‘blockbuster’ display (among which, for example, one could cite Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project at Tate Modern, London, in 2003). Instead, Lyotard’s and Chaput’s ‘manifestation’ was to the ‘large-scale retrospective what Joyce’s Ulysses is to the Odyssey,’ that is, a narrative attempt to make the process of exhibiting manifest.61 Between Ulysses and the Odyssey, the relation to a putative origin changes, as does the flow of the narrative: chronological and sequential in the latter, heterogeneous and non-linear in the former. In describing the effect sought by Les Immatériaux, Lyotard frequently invoked Virilio’s notion of ‘surexposition’ (‘overexposure’ or, equally, ‘overexhibition’), by which was meant the transformation of cities into sprawling ‘conurbations’ where ‘the opacity of construction materials is reduced to nothing’ and the architecture ‘begins to drift, to float in an electronic ether devoid of spatial limits yet inscribed in the singular temporality of an instantaneous broadcast’.62 What distinguishes this sublime cyber-landscape from Lyotard’s and Chaput’s stagecraft is precisely the exhibition’s opacity and depth – its ‘difficult’ greyness and theatrical obscurity – which impeded the seamless mobility and translucency of Virilio’s futuristic vision.63

The fact that the setting for this alternate vision of postmodernism was a ‘manifestation’ is crucial, for it is through an exhibition conceived as an immersive theatrical environment that the singularity of the modernist eye could be transcended and, at the same time, that transcendence in general, in the sense of Aufhebung, could be shown to be thoroughly unpredictable, literally unforeseeable.64 And it is precisely this quality that undermines the efforts of those seeking to discuss Les Immatériaux as a novel treatment of the ‘exhibition medium’. Lyotard aimed to challenge Shannon and Wiener’s communication diagram, in which ‘medium’ – one possible translation of the French ‘support’ – is the central term.65 Following Diderot’s allegorical fable,Les Immatériaux does not perform a ‘deconstruction’ of an exhibition medium, rather it draws attention to a specific ‘medium’ condition – that of painting – through the specific ‘exhibitionary’ form of an heterogeneous ‘mise en espace-temps’ in which competing discursive genres could be played out.66

As I have mentioned, it is likely that the inclusion in Les Immatériaux of Duchamp, Monory and Buren can be attributed directly to Lyotard. By 1985 Lyotard had published essays on all three, and having noted the conspicuous absence at the Pompidou of ‘painterly’ painters such as Newman – on which Lyotard had also written – one can infer that what the three artists have in common, in relation to Les Immatériaux, is their complex relationship to the ‘medium’ of painting and its manifestation. In particular, including these ‘painters’ would have allowed Lyotard to counter the Adornian thesis that the technosciences rendered the efforts of modernist avant-gardes obsolete, and to present three case studies in which ‘painting’ defied the repeatedly declared ‘end’ of its medium condition. This is not to argue that the covert presence of ‘painting’ in Les Immatériaux constituted proof that postmodern heterogeneity effectively challenged the divisions modernism had upheld between art, science and popular culture. Rather, the incidental presence of ‘painting’ in Les Immatériaux articulated one way in which the most modernist medium could relinquish its material limits in order to manifest the processes by which it makesseeing visible. How successful one judged this demonstration to be would ultimately determine whether one found Les Immatériaux to be a dramatisation of the sorrow prompted by the spectacle of the decline of Enlightenment ideals or of the uncertain jubilation elicited by the unfulfillable promise of the postmodern.

In contrast to Duchamp, Monory appeared in only one ‘site’, with a large four-panel painting from 1973 entitled Explosion.67 On each of the panels was the same ‘hyper-realist’ depiction of a commercial aeroplane exploding, the image progressively fading from left to right as the image went from a vivid blue on white in the first panel, to an almost white monochrome in the last. In the first panel on the left, the artist copied the image from a photograph; in the second, only the lower left-hand corner of the painting was painted ‘free hand’, while the rest of the canvas was covered with light-sensitive emulsion on which a slide of the same image was projected to produce a photographic impression; the third and fourth canvases were entirely ‘photographic’, with no trace of the artist’s hand. On the card in the exhibition catalogue corresponding to the ‘site’ of Monory’s Explosion, Lyotard adds a cryptic note: ‘The painter confronts the two ways. Catastrophe of painting?’ As Lyotard specified on the back of the card – an excerpt from his book on Monory published a year before Les Immatériaux – these two ‘ways’ are not to be understood as ‘Cézanne contra Niépce,’ that is, as different mediums, but rather as two different times between which the painter oscillates: the time of capitalism (measurable, accountable, predictable) and libidinal time (gratuitous, excessive, incapable of foresight or memory).68

Thus, it is not painting in the era of generalised technoscience that suffers the catastrophe of its own demise. Rather it is painting that provokes a chronological catastrophe by cloaking itself in the dandy’s melancholic blue-grey, and by stalling capitalism’s unshakeable positivism. As it was displayed in Les Immatériaux, Monory’s painterly disappearing act functioned as a museographic relic, a tangible trace of two contradictory impulses: on the one hand, the increasing discrepancy between the slowness of the painter’s hand and the immediate act of recording mass mediated ‘historical’ events. On the other, in its very disappearance, painting manifested its trans-medium resilience: forced to abandon a ‘sublime of transcendence’, it now engaged a ‘sublime of immanence’ as a way expose a new kind of questionable, technoscientific sublimity, one capable of testifying to the ever-expanding limits of experience through verifiable and accountable facts.69 By placing a painting on a wall, Monory allowed Lyotard to come the closest to a Salon-inspired hanging. But this sublime was only skin deep, immanent, and the clash between painting and the ‘mass media’ (in this case, photography) left only a paradoxical quasi-monochrome in its wake. In the end, it is colour that appears most apt at recording the catastrophe of the sublime’s ‘défaillance’, its seisure or failure.70

Colour, in both Monory’s Explosion and in the overall scenography of Les Immatériaux, underscored the distance covered since modernism’s ‘sublime of transcendance’, and the essential witness function performed by the ‘sublime of immanence’. According to Lyotard, Buren’s use of colour fulfills much the same function as Monory’s – that of testifying to a foreclosed logic of presentation, ‘in favour of the forbidden “colour”’.71 This last quote is from an essay Lyotard published on Buren in 1987, in which one cannot help but notice a similarity between Lyotard’s descriptions of Buren’s work and those of Les Immatériaux two years before: ‘For Buren, the support, the site, ideology are all the more noticeable as pragmatic operators when they go unnoticed, and the same goes for their exhibition. It is not a question of educating, but rather of refining the pragmatic tricks [ruses] that enable the works to be effective. But then, for whom, if it goes unnoticed? What is the destination of this meta-destined work? In any case, rather a sub-exposure (or sub-exhibition).’72

Buren’s significance for Les Immatériaux could easily be overlooked, as the artist’s work did not appear at all on the fifth floor of the Centre Pompidou, but only in the Epreuves d’écriture volume of the exhibition catalogues, whose white monochrome cover would prove the ideal foil for Buren’s invisible ‘sub-exposure/-exhibition’. In concealing the work of a painter known for his seemingly endless variations on colour, Lyotard may have had in mind a project Buren made in 1977 titled Les Couleurs: Sculptures. Buren’s project, produced for the Pompidou in its inaugural year, consisted in flags, bearing his famous motif of alternating white and coloured vertical bands, flying from Paris rooftops. The flags were to be seen from the Pompidou’s terrace, where telescopes were available to help visitors locate the tiny, often scarcely visible spots of coloured cloth on the horizon. In his account of Les Couleurs, Lyotard lays particular stress on the difference between experiencing the project after the fact, as documented through photography, and the actual effort of trying to spot the flags across the cityscape. While Buren’s own photographic records of Les Couleurs are, Lyotard writes, ‘monocular, linear, fixed, definitive’, the process of scanning the horizon from the museum had the effect of producing a ‘melodic curve’ capable of dispensing ‘rhythms’ that ‘disorganise and organise vision’, revealing in the process ‘to what extent the art look [le regard d’art] is subject to generally unconscious chronic conditions.’73 By removing Buren’s trademark stripes from Les Immatériaux altogether, Lyotard was sidestepping the medium-specific modernist distinction between Cézanne and Niépce, focusing instead on the far more critical question of how to ‘visibly expose what is not visible in the exhibition itself’?74

For Lyotard, this question was best posed by paradoxical artists such as Duchamp, Monory and Buren, for whom ‘painting’ represents a philosophical as well as phenomenological test, and for whom, moreover, the ultimate test resides in ‘painting’s colour. Just as for these ‘painters’ colour serves both to reveal and to dissimulate their respective mediums (pigment in the service of olfactory experience in Duchamp’s Torture-Morte and Eau de voilette; the bleached canvas turned photographic support for Monory; Buren’s elision of painting from the museum), the ominous and uniform ‘demanding’ grey of Les Immatériaux shrouded visitor and art work alike in a disorienting and unbound monochrome that simultaneously obscured the museum to better expose it as a fundamentally unmanageable, complex temporal space subject to ‘unconscious chronic conditions’. As Françoise Coblence has recently argued, the presence of colour in Lyotard’s work ‘remains insistent, as if coming from a time that nothing, no postmodern condition, can erase and which the insistence on anamnesis will bring back.’ Coblence goes on to suggest that for Lyotard, the phônè of the human voice is to the silence hidden within language what colour is to the invisibility immanent in ‘painting’.75

This equation between the immateriality of colour or human voice and the essential, ineffable element of what constitutes an artwork seems to lend credence to Lyotard’s and Chaput’s claim that Les Immatériaux ;‘merely presents to the eyes and ears some of the effects [of a new sensibility], as would a work of art’.76 But to grant Les Immatériaux art-like status, a number of operations of working-through, or anamnesis, must first be performed: of the modern in the postmodern; of the pictorial or fictional field in the exhibition space (as Diderot did in his report on the 1767 Salon); and of colour (or voice) in the pictorial/fictional field (as manifested in Les Immatériaux, in particular, through Duchamp, Monory and Buren). These permutations are what destabilise any authorship the anthropocentric ‘I’ may have over a ‘work’ – be it of art – and transform the singular subject into a participant in a collective heterologia.77

We may debate whether Les Immatériaux successfully dramatised these reversals, whether, that is, Lyotard and Chaput managed, as Lyotard put it, to ‘convert anxiety into joyfulness’ and ‘displace the tragic nature of writing into humour’.78 Yet what is undeniable is that, true to Freud’s definition of anamnesis as a first step in the analytic treatment, the working through ofLes Immatériaux has only just begun – not in search of any definitive origin or answer, but as a potentially endless chain of phrases in which Lyotard’s commitment to an ‘initial forgetting’ at the Centre Pompidou in 1985 still pressures us to take part.79