Fig.1

Jessa Fairbrother

Green Garden Trilogy 1 in Conversations with My Mother (2016)

© Jessa Fairbrother

‘This is my story of severance’, begins the text that introduces Jessa Fairbrother’s artist book, Conversations with My Mother 2016.1 The page-long account – the only words in the book of photographic images – sets out the context of the publication’s genesis and content: a period of mourning for the loss, first anticipated and then actual, of Fairbrother’s mother, and of her discovery of the probability that she herself would not bear children. ‘It explores’, the text continues succinctly, ‘the relationship I had with my mother and my own inability to become one.’

This article looks in detail at the context for the making of the book and at the artist’s expression of complex emotions, understood here as of significance and value in and of themselves, through a close examination of her hand-worked photographic imagery. The book’s narrative is biographic – the opening sentence of the artist’s text unashamedly declares that it is ‘my story’ – but within it lie clues to psychological mechanisms that can be widely recognised and understood.

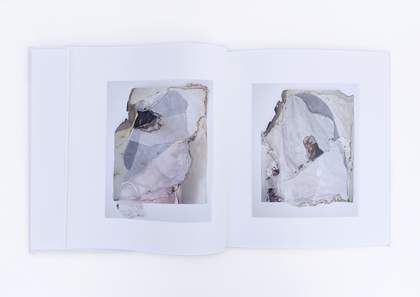

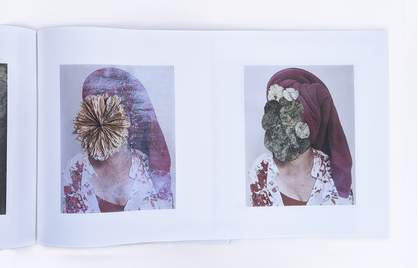

The book’s central themes unfold within its sequencing of images, a carefully orchestrated ‘call and response’ between the artist and her mother, the painter and printmaker Shella Fairbrother. Photographs of or by Jessa Fairbrother are typically reproduced on the left of a double spread; those relating to her mother, as she lived her last months with cancer, are on the right, suggesting a conversation of sorts, though this is of course a conceit, a vehicle for the expression of emotions, needs and memories, filtered through the artist’s consciousness and creative purpose. Within the book the pairing of an image with a blank page indicates which of the two is ‘talking’, and where the response is, poignantly and ambiguously, silence. In the volume the mother is often shown as a distant figure working in her garden, her face lost under clouds of small yellow and orange flowers – cyphers for the evening primroses she loved to see self-seed – embroidered onto the original source photographs (fig.1). Or she appears in head-and-shoulders portraits, her eyes closed and partly transfigured by the towels or scarves wound around her head, disguising the loss of her hair as a result of chemotherapy. Simulacra of simulacra, these photographs are representations of how the artist chose, after her mother’s death, to remember and present her in her last months; they do not reflect the choices or voice of her mother, except insofar as embodied and adopted by the daughter.2

Fig.2

Jessa Fairbrother

Double page spread in Conversations with My Mother (2016)

© Jessa Fairbrother

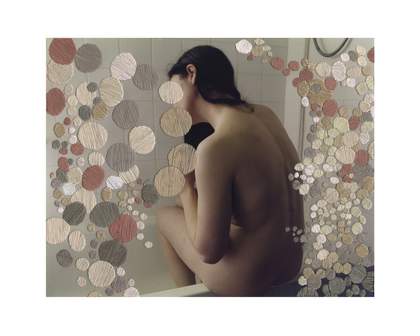

Fig.3

Jessa Fairbrother

Untitled image in Conversations with My Mother (2016)

© Jessa Fairbrother

Counterbalancing these are images of Fairbrother mirroring her mother and re-enacting the latter’s experiences. She is shown, for example, with a towel wrapped around her head (fig.2) or, after her mother’s death, wearing the NHS wig given to her mother when she lost her hair (fig.3); it was the only item that retained her mother’s smell. Such images can be seen as a performance and outward manifestation of an attempt to hold on to, and to incorporate, the lost loved one within the self.3 And then – representing a conversation that was barely had at the time because it was so overshadowed by the approach of death – there are photographs of the artist’s face and body that explore her feelings about not bearing a child.

Fig.4

Jessa Fairbrother

Double page spread in Conversations with My Mother (2016)

© Jessa Fairbrother

An early double page spread reproduces photographs taken by mother and daughter before their lives were changed by the diagnosis of what proved to be an aggressive cancer; it serves to introduce the special relationship between the two women (fig.4). In order to help strengthen the connection between them (they had not been getting on as well as usual), Jessa – then living in Sheffield while her mother lived in Bristol – had proposed that, using a disposable camera, one took a photograph of something, whether memorable or banal, and then mailed the camera to the other, and so forth. The project had no particular purpose and the artist remembers feeling disappointed when she eventually developed the camera’s film; only much later did this exchange assume a poignancy and become the prototype of the concept of a visual conversation central to the book. The mother’s images included shots of the garden, the path leading to her garden studio, and one of the printmaking studio where she went to make work on the other side of the city. The artist’s included plants, breakfast on a table, and an image of a positive pregnancy tester, a record of a conception that ended in an early miscarriage. Developed during her mother’s last months, these photographs were never discussed but testify to their shared trust and willingness to experiment artistically.

Most of Conversations with My Mother focuses on the period following the diagnosis. On hearing the news by telephone in March 2012, Fairbrother, later joined by her husband, went immediately to Bristol, leaving her job as a part-time college lecturer. Living with her mother over the next nine months, she witnessed her mother’s treatment and decline. Fairbrother did not have a studio space within the house – her mother’s studio was at the bottom of the garden – and remembers feeling confined and trapped in these months.4 She produced her self-portraits in her bedroom or the bathroom, using a tripod and self-timer. Some show her with a stocking over her head, expressing her sense of suffocation. Once or twice she asked her mother to photograph her, echoing their earlier collaboration involving a disposable camera together. In doing this, she was trying, as she wrote in the book’s introductory text, ‘to make sense of things that had no sense except sadness … We strived to understand and love each other more completely; we looked at each other seeking resemblance, resentment, entanglement and reliance’.5

This was Fairbrother’s second experience of losing a parent to cancer. Her father Max Fairbrother, a graphic designer and photographer, was diagnosed with the disease in March 2000. The eldest child of two, Jessa was working in London in a literary agency, having just abandoned her hopes of becoming an actress; but on receiving the news she moved back in with her parents, who were then living in Wales. She found a post as a junior reporter on a local newspaper and helped her mother look after her father. Interviewed in 2018, she remembered feeling distraught at the impending loss of her father and angry at her loss of control of the direction of her own life.6 Her world had been turned upside down, and in this pre-internet period the move to Wales meant that she lost contact with her friends. Her father died in June 2001 aged only fifty-four, when Fairbrother had just turned twenty-six. Looking back, she felt that the trauma of losing her father at such a relatively young age was softened by her sense that he had lived a full life and by the fact that she still had her mother, who had always been more central to the life of the family (her father had seemed a more absent figure, always busy in the studio). Yet this early experience of profound loss was formative and an undeclared element of the context of Conversations with My Mother.

After her father’s death, and in response to it, Fairbrother decided to follow in his footsteps and become a photographer. She took a Higher National Diploma (HND) in photography and at the end of the course embarked on a project that involved photographing benches with memorial plaques on the Pembrokeshire coastal path. There were a particularly high number of such benches on the route and their presence created some controversy in the community, with some people resenting the ‘privatisation’ of public spaces. Fairbrother had thought of undertaking a meditative walk along the coastal path, photographing the benches as she went, but she rejected this concept as being too much about herself. She recognised the project was linked to her feelings about losing her father but had not wanted her work to seem overtly autobiographical and typically deflected self-analysis, perhaps because she was unable to face her feelings about his loss more directly. Instead, she photographed the benches and, using her experience as a local reporter, tracked down, as far as she could, all the families who had erected the benches, recording details about the people who had died, including why they had died (so often it proved to be cancer). In 2004 she successfully applied to the Arts Council for a grant to create a community project, showing this body of work in exhibitions in local libraries in the county. Her application did not mention her own experience of loss but instead spoke about the project as being about ‘the public demonstration of grief’. The question of how we acknowledge the presence of someone no longer alive, however, was and remains important to her on a personal level, not least because her father had chosen to be buried anonymously, in a field near the house with nothing more than a rock as a marker.

Fig.5

Jessa Fairbrother

Untitled image from I Did series 2007

© Jessa Fairbrother

Developing this theme, Fairbrother went on to produce a body of work around absent or lost bodies that she used to apply to join a MA course at the University of Westminster in 2008. Working as a freelance photographer for a newspaper in the Sheffield area, she had heard about a local event to teach women how to preserve their wedding dresses. Intrigued, she set about locating women who had kept their wedding dresses, and photographed them with the items in their homes, taking care to make sure the shots did not reveal whether the women were married, divorced or widowed (fig.5). ‘The dress became like the body’, Fairbrother commented in 2018:

It symbolised the hopes and aspirations that they had had at that moment. And it symbolised unrealised hopes and ambitions. That’s probably where I started to think about yearning although I would not have articulated it then as yearning necessarily: I think I was thinking that it was still about loss … The wedding dress is such a powerful object because it points in two directions – it points forward and backwards. It hovers in this amazing space … the object brings together the younger body against the older body. There are very few things that can do that.7

Importantly, the wedding dress is also an icon of the familiar narratives of ‘living happily ever after’, and of women finding their fulfilment through marriage and the home. Having lived through the death of a father and seen its consequences in the life of her mother, Fairbrother was particularly sensitive to the concept of ‘happy endings’, a deep-seated narrative structure around which, almost inevitably, people find themselves navigating, one way or another. ‘It is ridiculous but we all do it … We are yearning for security and life is so insecure. Nothing is stable and we are constantly surprised … There is a huge amount of grief that comes from realising that you are not going to get your happy ending.’8

It was during her mother’s last months that Fairbrother had to confront the loss of previously expected ‘happy endings’ in her mother’s life and her own. Having moved to Bristol in 2007, her mother had become involved with the Spike Print Studio at Spike Island, an artist community and arts venue. She exhibited rarely, and only in local events, and was happy to pursue her painting and printmaking without external markers of success alongside rearing two children. However, she was in Jessa’s words ‘a proper artist’.9 Death came before she had been able fully to spread her wings following the years of her bereavement and her subsequent move to Bristol. According to her daughter, ‘She was sixty-four and it was like she had only just got going. I think that is incredibly sad. She did not get to do what she wanted with the last twenty years [she should have had].’10

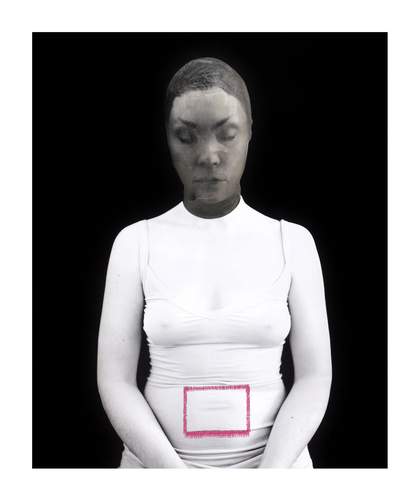

Fig.6

Jessa Fairbrother

Untitled image in Conversations with My Mother (2016)

© Jessa Fairbrother

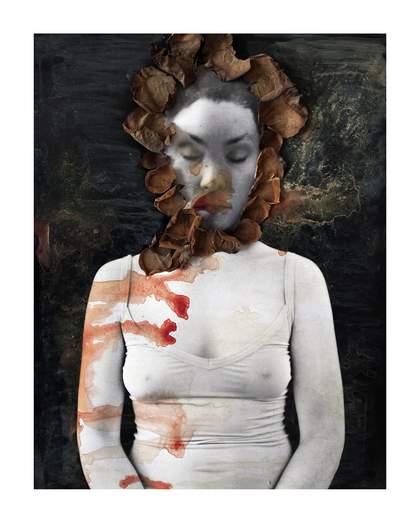

Fig.7

Jessa Fairbrother

Untitled image in Conversations with My Mother (2016)

© Jessa Fairbrother

Fairbrother’s sorrow and rage about her mother’s illness were compounded by doubts over her ability to give birth. ‘When I was making Conversations with My Mother, I was so angry. You see mums in the park with their mums and their babies. And it is like that should have been me.’11 The cause of her reduced fertility was never identified but with three early miscarriages over a couple of years, including one after her mother’s death, she lost hope of conceiving naturally and had to come to terms with the idea of being ‘child-less … or child-free’.12 A bone-crunching sadness is suggested by bleak, monochrome images of the artist’s body, with a dark pink empty rectangle over the womb area in one and, in another, what looks like horizontal drips of fresh blood over the torso (figs.6–7). The artist remembers a painful conversation with her mother, when it was not yet clear that it was unlikely that Jessa would bear children, about favourite children’s names, with the mother taking pleasure in thinking about a future that she herself would not see and trying to insert herself into that future through suggesting possible names for children that her daughter might yet have; but generally the topic was overshadowed by the mother’s impending death and too much to bear in addition to what already had to be borne. Conversations with My Mother is as much about conversations that were not had, and those that were imagined and longed for, as much as remembered or re-experienced moments of connection between mother and daughter.

The images in the book were made simply as individual works, without the intention to produce a volume. Fairbrother created some work for a separate project during these months but made relatively little while she spent time with and cared for her mother. However, of the handful of images she made of her mother and herself in these months, she ordered many copies, and this gave her the freedom to experiment. She remembers that she soaked a few prints in a wheelbarrow filled with water in the garden for a few days in the weeks before her mother’s death, something she had not tried before and an act that suggested a type of ritual cleansing in an object associated with her mother. Most of the work on the prints, however, happened afterwards.

For Fairbrother the following two years are a blur. ‘There were days when I just cried. There were months where I can’t remember what happened.’13 ‘I cried for my loss of feeling the hug of her body, her touch, her laugh. I cried in sorrow at the abrupt suspension of future narratives, for the mother I would not hold again and for the child who would never hold me.’14 She and her husband stayed in her mother’s home and she took a part-time job as a support assistant in a local junior school. It was important for her that work provided some form of routine but was undemanding, and that it provided a nurturing and kind environment. Shortly after her mother’s funeral Fairbrother joined an open-plan artist studio complex, and three months later began to work there every afternoon. The space was occupied mostly by painters. She recalled:

I learned so much from them about how to be free, how to just try something. They had an interesting way of working that was completely alien to me, and this gave me permission to chop things up, paint on things … I thought no one was paying attention to me. I thought it was because they were not interested, but it was because they did not know what to say. There I was putting up incredibly traumatic pictures in my studio in a public space, and of course they did not know what to say. I was also a wet rag.15

She found out subsequently that the other artists would go and have a look at her studio space when she was not there, and knowing of her grief they would keep on inviting her out to socialise. But, she says, ‘because no one was [seemingly] paying attention to my work, I just thought I would go on. I knew it was important, I knew it was urgent, so I kept going’.16

Fig.8

Jessa Fairbrother

Untitled image in Conversations with My Mother (2016)

© Jessa Fairbrother

Fig.9

Jessa Fairbrother

Fold-out double page in Conversations with My Mother (2016)

© Jessa Fairbrother

Fig.10

Jessa Fairbrother

Fold-out double page in Conversations with My Mother (2016)

© Jessa Fairbrother

The techniques used to create the photographs reproduced in Conversations with My Mother were innovative, and in themselves evoke the interplay of absence and presence involved in loss, the alternately dark and destructive, as well as loving, aspects of grief, and the processes of occlusion and translation that occur when what is private and amorphous is made public and shared as art. As already mentioned, Fairbrother soaked some photographs in order to be able to peel off the paper backing, leaving just a layer of emulsion: their appearance of having been grievously damaged, skinned as it were, and of being left extremely fragile, evoke the heightened sensitivities of physical illness and grief. Charring the edges of the images with a cigarette lighter introduced new shapes and textures – another visual metaphor for the losses suffered by mother and daughter; it also suggested that, in the midst of the experience of loss and grief, vision itself was scorched. Some images were covered with tissue paper, evoking a tender veiling of the past or, in other instances, a more emotionally ambiguous or suffocatory shrouding of the subject (fig.2). Others were painted, adding a different type of layering (fig.8). Washes of acrylic paint added new textures and made the underlying image ‘other’ or ‘abnormal’. Paint was also brushed onto a sheet of glass on top of one image, which was then rephotographed through the glass (fig.9, left). Dried flowers – nasturtium and rose petals from the garden, clivia blooms from a houseplant given by a family friend, and a miscellany from the funeral arrangement – were collaged onto the photographs, around and over the faces of mother and daughter (figs.10, 7). The smothering of the mother’s face with flowers implied a disturbing element of monstrosity and suggestion of burial, as well as decoration.

For Fairbrother, reworking the same image and finding new things to do with it were ‘just different ways of saying I love you’. She continued: ‘You look for different ways to say it in order to make it meaningful, to have the connection.’17 There is undoubtedly, too, an expression here of what the philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin, writing in 1928, called ‘the gaze of the melancholy man’:

Mourning is the state of mind in which feeling revives the empty world in the form of a mask, and derives an enigmatic satisfaction in contemplating it … The world is revived in a masked form, in a masked way, not as a mask, but through a form of masking and as its result. The masking does not precisely conceal, since what is lost cannot be recovered, but it marks the simultaneous condition of an irrecoverable loss that gives way to a reanimation of an evacuated world.18

In this light, the use of paint and paper to veil the images, or of collaged dried flowers to cover or eradicate the faces of mother and daughter, suggests both a pained recognition of an ‘irrecoverable loss’ of that which now cannot be properly seen and an attempt to reanimate an ‘evacuated world’ through creative endeavour.

Fig.11

Jessa Fairbrother

Untitled image in Conversations with My Mother (2016)

© Jessa Fairbrother

Fig.12

Jessa Fairbrother

Untitled image in Conversations with My Mother (2016) seen through a transparent overlay with patterns of perforations over the body area

© Jessa Fairbrother

Fig.13

Jessa Fairbrother

Untitled image in Conversations with My Mother (2016)

© Jessa Fairbrother

It was around this time that Fairbrother began to pierce and embroider photographs for the first time, a technique that defamiliarised the imagery and, in psychological terms, suggested an amelioration of grief and a rebalancing of emotions. On a photograph in the book showing herself sitting pensively in the bathroom – a place for her to contemplate her body and an echo of her mother’s enjoyment in taking baths – she sewed swarms of large and small discs, suggestive of bath bubbles and thought bubbles, in flesh-toned coordinated hues, either side of the figure (fig.11). On the transparent overlay of this image – a device that suggests a veiling of reality – she pricked a delicate pattern of imperfect circles over the area of the body, as if a barely visible tattoo (fig.12). Pushing a needle from the underside of the paper created a tactile sensation, inviting the book-user to gently touch the page and imagine touching the figure. Repeated for many works in the volume, and thereafter a key element of Fairbrother’s practice, this pricking and sewing transformed the photographs into unique objects, ones with three-dimensionality and haptic qualities. Unashamedly decorative and feminine in association, the delicate embroidery and linear patterns of prick marks can be seen as connoting repair, tenderness and consolation. The organic qualities of these additions – they seem to multiply, move and grow – appear a tacit acknowledgment of the existence of vital forces alongside those of loss and death. Fairbrother was particularly aware of this when she used a hand-sized fragment of a pink silk shirt that she and her mother both favoured, burning it – the remains now a framed item in the artist’s studio – as a template for the wavy patterns sewn over the photographs of her mother wearing a scarf or of herself wearing her mother’s wig (figs.13, 2). The shape reminded her of hair, the contours of maps, the eddies of water and the tracks of tears.19

The idea of making an artist book using these images that she had made during and after her mother’s illness took shape two years later. In Bristol Fairbrother knew a number of artists involved with photobooks through the IC Visual Lab, an arts organisation focused on photography, film and visual archives. However, it was only a chance conversation in late 2014 that prompted her to consider making an artist book from her hand-worked images and creating a new artwork in book form. She spent much of 2015 coming to an understanding of what an artist book was, finding out about how to make one and creating a dummy for presentation at a formal review of artist portfolios in Houston in 2016. She initially planned to make an edition of forty-five copies, but as the evolving concept meant that the book became a unique object and required more hand-worked pages the edition size was reduced to sixteen. Working with a designer and a bookbinder, she settled on which images to include and their sequence, where to include pages of transparent paper and how to produce the two fold-out pages within the book (for Fairbrother, the opening of the folded pages conjured the sense of the discovery of secrets) (figs.9, 10).

Fig.14

Untitled photographs by Max Fairbrother of Shella Fairbrother, taken in 1975 and reproduced in Conversations with My Mother (2016) by Jessa Fairbrother

© Jessa Fairbrother

The book ends with what had been a secret, or at least something previously unknown to the artist: a pair of photographs taken by her father in early 1975 and found after her mother’s death in a box of his works (fig.14). They show her mother Madonna-like in a smocked white nightgown, heavily pregnant with Fairbrother and deeply pensive. Although she is depicted alone, the historical associations of the pose and dress suggest a sacra conversazione (typically, in Renaissance art, between the Virgin Mary and saints), echoed in modern-day terms in the volume’s theme of ‘conversations’. The decision to include these private, family images in the book was a difficult one, but their theme of anticipated motherhood brought full circle the story of her mother’s last months and of the artist’s struggles to conceive. They also represented a period of complete union between mother and daughter, a time of the first conversation, as it were. Delayed by the period of mourning and deep grief, it was some time before Fairbrother chose to investigate medical help for her condition and when she did so, aged nearly forty, she eventually decided, with a surprising sense of relief and release, not to pursue this difficult path.

‘Somebody said to me, or I read it somewhere, that your parents give birth to you twice – when you are born but also when they die. I think that is an interesting idea because you are inextricably linked to your parents, which is really complicated. When they die you can be deeply, deeply sad and free.’20 For Fairbrother, the experience of working on the photographs and later of making Conversations with My Mother sometime after her mother died allowed her to revisit and reprocess her memories and her feelings as an exercise in love and catharsis. Making art was itself an expression of the gratitude she felt for the gift of creativity that, she recognised, came from both her parents. It also denoted a wish to survive and distance herself from this trauma, while reaffirming her identity as an artist, temporarily lost while she had assumed the role of carer. But none of the positive, therapeutic aspects of the making of Conversations with My Mother diminished the personal pain, in all its individual complexity, exposed therein: ‘severance’ denotes a sharp-edged, irrecoverable finality.

‘When confronted with any loss and mourning’, Esther Dreifuss-Kattan wrote in Art and Mourning: The Role of Creativity in Healing Trauma and Loss (2016), ‘art can be one of the most powerful tools, as words alone often seem inadequate to the exploration of such emotionally charged and unknown territory.’21 This simple point is true for the viewer of art as much as for the artist. With Conversations with My Mother, Fairbrother put herself, her mother and their relationship in the frame; much of the volume is very specific to their lives in this one particular period, although this may not be immediately apparent to a casual reader of the book. When asked how, in retrospect, she felt about this public disclosure of deeply painful personal narratives, Fairbrother said:

I have thought a lot about the purpose of sharing this work. When presenting it through talks and lectures I am often overwhelmed by the stories that come flooding back to me. It makes me aware that the thing I made, which was so personal, has touched other people – so there is the thread between my story and someone else. And as my own familial thread has been severed in two directions it is a good feeling to know my work continues to make meaning beyond me, that there will be evidence, after I myself am gone, that I really existed. This sentiment goes full circle to the memorial benches, really, which is all about trying to leave a mark on the world – to say you were really here; that people cared about you and you cared about them.22

Conversations with My Mother is a memorial to love, to grief and, in its cared-for material qualities, to life. It is also a multivalent work of art, something Fairbrother created and laboured over, and it is important to her that it is seen as such, and not as catharsis or therapy. She used to struggle to find an answer when people enquired if making the book had made her ‘feel better’. With the passage of time, however, she senses a basic commonality of experience, or of the human condition, behind the question. ‘I think when people ask it they vocalise their own sadness: the book touched them and they want to let me know that. And if I say that I do feel better then they have permission to feel better, too.’ She continued: ‘And if we both feel better we can fend off the abyss. The thing that we can see out of the corners of our eye. Because during this whole period of grieving I looked right at it, and it was dark. Now I just catch a glimpse every now and then. I think that makes me really conscious of being alive.’23 Much can be said about the potentially positive aspects of loss, seen in socio-historic terms and when what remains after the loss is focused upon and used to create new representations and meanings.24 But, as the artist’s reflections suggest, the sense of an ‘abyss’ and of personal mortality within this or any unvarnished engagement with loss and grief operates at a level beyond questions of positivity or negativity, or of healthy and unhealthy responses to painful circumstances. Instead, at its extremes, it obliquely exposes the limits and fragility of individual consciousness.