Nineteenth-century painter John Constable is renowned for his views of the English countryside, and the artist himself described his art as one of ‘Rural Landscape’.1 Yet when we survey the subjects Constable selected to be engraved by David Lucas for Various Subjects of Landscape, Characteristic of English Scenery 1830–2 (henceforth English Landscape) as a retrospective of his career, we find urban subjects among them: towns and cities of many kinds depicted at different stages in their history. These include London, a metropolis that at the time had a population of more than one million people, and where the artist worked and exhibited; Hampstead, the hilltop London suburb where he lived, a place with spectacular views of the city; the fashionable Sussex seaside resort of Brighton, the fastest growing town in Britain; and the international ports of Harwich in Essex and Great Yarmouth in Norfolk. Constable also portrayed cities that grew slowly, notably the cathedral city of Salisbury (or New Sarum), and some that declined completely, such as the neighbouring deserted city of Old Sarum. He also depicted Dedham in Essex and Stoke-by-Nayland in Suffolk: both had been major cloth manufacturing centres in Tudor times, and by Constable’s time the former had transformed into a smart Georgian town for marketing and corn milling, while the latter had declined into a small rustic village.

These places were significant to Constable both politically and personally as changing centres of power, as documented in the letterpress (printed text) in English Landscape, which expands the scope of the scene shown in each print. The text for Brighton, facing a scene of fishing boats on the beach, describes how a ‘fishing town of so little importance should in the space of a few years have become one of the largest, most splendid and gayest places in the kingdom’ its rise so ‘connected … with the Metropolis’, that it might be characterised as ‘the marine side of London’. The print Stoke-by-Neyland c.1829 (British Museum, London) focuses on a majestic church towering over a small row of cottages; the letterpress notes how such ‘magnificent structures are often found in scattered villages and sequestered places … once the seats of clothing manufactories, and which were so flourishing during the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII’ and ‘greatly increased’ by the ‘skill and industry’ of Flemish weavers escaping from Catholic persecution during the reign of Elizabeth I, ‘the glory and support of Protestant Europe’. The deserted citadel of Old Sarum is described as having been a major political as well as religious centre in the middle ages, where ‘the wily [William the] Conqueror, in 1086, confirmed that great political event, the establishment of the feudal system’. Published in 1834, when Old Sarum’s political power had finally been extinguished through electoral reform, Constable’s print was accompanied by a resonant New Testament quotation: ‘Here We Have No Continuing City’.2

Fig.1

David Lucas after John Constable

Sir Richard Steele’s Cottage, from English Landscape 1830–2

Mezzotint on paper

132 × 187 mm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A view of London from Hampstead, engraved after a painting by Constable, displays such periods of urban transformation (fig.1).3 It shows two sides of Hampstead’s cultural heritage on Haverstock Hill: on the right, the house of eighteenth-century man of letters Sir Richard Steele, and on the left, the Load of Hay Tavern, visited by day trippers from north London and by seasonal labourers harvesting the adjacent hayfields to supply horse-drawn transport. The Tavern, as we see, is a stop for the stagecoach that Constable took most mornings to commute from his house to his studio.4 The vista looks over a murky middle distance – Kentish Town and St Pancras – to focus on the shining churches of the City of London, notably St Paul’s Cathedral, its bright dome crossed by a plume of black smoke; probably, if the view is geographically correct, emanating from the Imperial Gasworks by the Regents Canal, which was regarded as a landmark of modern progress.5

The above examples indicate that Constable was no less concerned with matters of urban transformation, and with types of towns and cities as well as the places themselves, than he was with rural ones. Constable’s prints in English Landscape, which include wide prospects and partial views, show stages of a settlement’s history. The letterpresses take a long view of towns and cities, covering periods of antiquity as well as modernity, and of their geographical connections, including those of trade, immigration and conquest beyond Britain. In this way, they are part of Constable’s wider concern with landscape history and narratives of change.6 The focus on churches in changing surroundings in the above examples, and the biblical verse on the decline of Old Sarum, also indicate the importance of Constable’s religious perspective: the painter was one of many observers concerned with the place of the Anglican Church in the changing world of the nineteenth century, and with the political as well as ecclesiastical meaning of landscape.7

By its very format as a publication English Landscape represented the intersection between Constable’s art of landscape painting and the conventions of topographical texts and images.8 Topographers produced relatively affordable publications that featured descriptions of places along with documentary illustrations. One such topographical publisher was John Britton, who was well known in the nineteenth century for his publications that sought to raise the cultural status of topography as a literary and artistic genre. He did so by including newly researched letterpress that explored the literary, socio-historical and cultural associations of landscapes, and expertly drawn, finely engraved illustrations that displayed pictorial effect as well as factual documentation. Moreover, he sought to widen the scope of topography by encompassing new, modern developments – railways and theatres as well as castles and cathedrals – to chart past and present as part of the nation’s progress, especially with regard to political and religious reform.9

This article addresses the place of towns and cities in the works of Constable and Britton, and their respective views of urban history in the changing English landscape. These histories are placed in a wider field of urban representation in which matters of religious as well as political reform were central, particularly in works on cathedral cities, for which Britton was famous. The article first considers the place of London, Bristol and Worcester in Britton and Constable’s exchange of letters and the lectures they delivered; this is followed by a survey of their respective works on Salisbury, a city with which both individuals had a personal and ideological connection. The article then turns to the exchanges between Constable and Britton during the production of English Landscape, focusing on the subject of Old Sarum.

The landscape artist and the topographer

Britton and Constable were near neighbours in north London, working a few streets away from each other in Bloomsbury.10 For much of their careers, however, they inhabited different cultural worlds. They came to London from contrasting rural backgrounds – the artist from a prosperous part of Suffolk, the topographer from an impoverished village in north Wiltshire. They expressed contrasting political views: Constable was a reactionary, conservative, High Church Tory, and Britton was a reformist, liberal, Low Church Whig. This meant that they held opposing attitudes to the Great Reform Act of 1832, which proposed modifications to the electoral system to allow for fairer representation of the people of England and Wales, and differing views on the authority that Church and State should hold. Nevertheless, they occupied increasingly common ground. Britton’s liberalism became more moderate, as he aligned political reform with a longer progressive history. This included the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century, when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the Roman Catholic Church, and the political Parliamentary Reformation of the early nineteenth century, which enfranchised newer, expanding towns and extended voting rights to many more male property holders. Meanwhile, Constable’s conservatism took in progressive interests such as popular science and public education.

The creation of an enlarged audience was part of Britton’s liberal view of landscape, as well as a financial necessity and form of social advancement for Britton himself. Like many contemporaries, Britton regarded the reform of his time not only as a parliamentary matter, but as a wider movement to reshape society. This involved remaking the landscape to advance a new world of commercial progress and social opportunity, and extending learning about the changing landscape through public lectures, scenographic entertainments and affordable publications. Britton promoted theatrical shows in London in which he made use of panoramas and dioramas for their combinations of minute documentary detail and dramatic effect. Constable was more critical of such entertainments, which seemed less natural than landscape painting, as well as too conspicuously commercial for an academically ambitious artist. However, it is evident that aspects of such entertainments appealed to the painter, sometimes in spite of his professed judgement, and their influence may be seen in dramatic large-scale exhibition pieces like The Opening of Waterloo Bridge (‘Whitehall Stairs, June 18th, 1817’) exhibited 1832 and Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows exhibited 1831 (both Tate).11

Britton wrote his own life into his topographical publications, indicating the progression of his career and the barriers he faced along the way, such as in the memoir prefacing the final volume of his The Beauties of Wiltshire (1825) that he sent to Constable as an ‘account of the adventures of John Britton’.12 Constable himself wrote aspects of his life into English Landscape, although apart from the opening image that depicts his birthplace in East Bergholt, Suffolk, the publication provided little detailed documentation of his attachments to the places portrayed.13 This was supplied for the reading public by C.R. Leslie in his Memoirs of the Life of John Constable, first published six years after the artist’s death in 1843, and illustrated with prints from English Landscape.14 The ageing Britton published his Autobiography in 1850, seven years before his own death, with the assistance of his young secretary T.E. Jones. As such, the works of both the painter and the topographer might be read for the intersection of their lives and the landscapes that they studied.15

Throughout his career Britton’s aspirations for topography were overshadowed by the critique levelled by Henry Fuseli – artist, writer and Professor of Painting at the Royal Academy – who regarded topographical views as mere ‘map-work’, of local interest only to inhabitants, travellers or antiquarians.16 Britton railed against Fuseli’s remarks but he did so equivocally, conscious that there were indeed view makers whose work was narrowly local and descriptive and who tainted a term he was trying to restore and renovate. In The Fine Arts of the English School (1812), at the urging of artist J.M.W. Turner, whose view Pope’s Villa, A Landscape 1811 is featured in the publication, Britton complained that the ‘whole class’ of landscape artists had been stigmatised for the tastelessness of some of its members.17 Britton remained mindful of the lowly reputation of topography, in both literature and art, in his ambition to reinvent the term as a cultural keyword, to enhance its scope geographically and historically, and to raise its status by means of original research and fine illustration. The engravings were designed to display effect as well as documentation, and to prompt literary associations, in order to portray the manifold relations of people and place.

An advertisement for the second edition of English Landscape that was published in the Literary Gazette on 4 May 1833, which Constable largely wrote, goes to great lengths to claim the work to be of greater cultural value than many topographical publications. While the latter were undertaken to make money by those with little personal knowledge of, or feeling for, the places depicted, Constable stated that his own publication ‘originated in no mercenary views’.18 A promotional review that appeared two weeks later in the next number of Literary Gazette, which samples from the introduction and prospectuses for English Landscape and which Constable may have had a hand in preparing, celebrates work of the engraver David Lucas in expressing the ‘vigour and originality’ of ‘Mr Constable’s feeling’: ‘There are few things we more dislike than landscapes which are mere maps of the places they represent. This is a defect of which Mr Constable can never be accused. He always introduces into his works some powerful and striking effect, which redeems them from topographical tameness.’19

We first encounter Britton in Constable’s published correspondence in a letter that was sent to Constable from his fiancée Maria Bicknell in November 1814. Bicknell reports that she had ‘met with some most agreeable people here [in Brighton], Mr. & Mrs. Britton, you must know them by name. They have given me an invitation which I shall certainly avail myself of, to see their fine collection of paintings.’20 Constable would have known Britton by name, for the latter was then at the height of his renown, having published Fine Arts of the English School and issued major volumes on Salisbury Cathedral and on Wiltshire more widely – a county to which Constable was turning in his work.21 Britton’s ‘fine collection of paintings’ largely consisted of watercolour drawings that were designs for engravings in his publications. Some were made by Britton, a self-taught draughtsman; some were loaned or purchased, for example those by Turner, John Sell Cotman and Edward Dayes; and an increasing number were commissioned from young draughtsmen and engravers, notably Fredrick Mackenzie and John Le Keux, or produced by Britton’s own pupils, including Samuel Prout, George Cattermole and W.H. Bartlett.

There is no record of the prospective visit to Britton’s house that Bicknell mentions, and it was more than fifteen years before Britton appeared in Constable’s correspondence again, in a series of exchanges between them in 1830 regarding the publication of English Landscape. The correspondence is little more than notes, nothing like the long letters they both sent to other friends, patrons and professional associates.22 It was a correspondence largely initiated by Constable, who undertook a number of transactional exchanges of this kind with individuals he consulted during the making and marketing of English Landscape. Yet as the content of the notes suggests, there was arguably a closer personal relationship than the paper record indicates, with visits and gifts, as well as misunderstandings and differences of opinion.

The 1830s saw something of a convergence between the work of Britton and Constable more generally, with the painter’s efforts to extend his audience by giving public lectures and publishing English Landscape. Britton’s career was now in decline, hastened by the economic crash of 1825, which had escalated from a series of speculative projects within the financial system and brought down many producers of finely produced illustrated volumes.23 Britton was forced to contribute to cheaper books, pamphlets, annuals and magazines, for which he was often paid by the page, to subsidise his own costly, loss-making works.

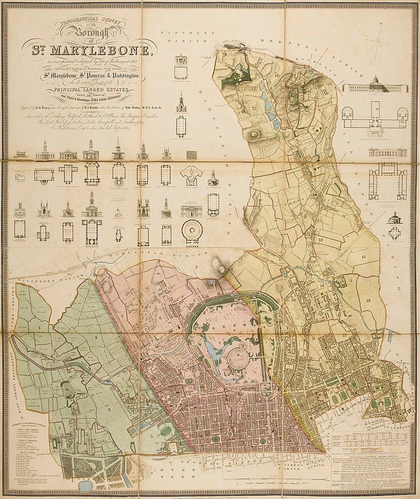

Fig.2

John Britton

Topographical Survey of the Borough of St. Marylebone, as Incorporated & Defined by Act of Parliament 1832. Embracing & Marking the Boundaries of the Parishes of St. Marylebone, St. Pancras & Paddington 25 June 1834

Engraving

1100 x 910 mm

In 1835 Britton sent Constable on approval a copy of his magnificent display map Topographical Survey of the Borough of St. Marylebone (fig.2). Britton may have thought the map would appeal to Constable personally: it showed the route of the painter’s journey from Hampstead to Charlotte Street, the new University of London where his son John was studying science, as well as key locations in Constable’s network of friends and collaborators, including the residences of Leslie, the engraver David Lucas, and Britton himself. The Topographical Survey of Marylebone made a more public statement; it represented Britton’s efforts to show that cartography could be more than ‘map-work’; rather, it could produce a work of ‘beauty’ that in this case portrayed the history and prospects of a key place in London’s development.24 Britton seems to have overlooked the fact that the map’s message would have been politically provocative to Constable, for it commemorated the passing of the Reform Bill that enfranchised Marylebone as a borough. Leslie records that in one of his reactionary outbursts Constable discussed his fears of ‘Reform fever’,25 and the map included places with a radical reputation like St Pancras and Paddington; ‘slimy marshes’, according to Constable, where reform fever festered. Although the map’s reformist message was a moderate one, showing ancient parishes and displaying plans and elevations of new churches and chapels to accommodate the increasing urban population, this seems not to have placated the painter.26

Constable appears to have accepted the map of Marylebone on sufferance, as is evinced by Britton’s reply:

As you say you took the Marylebone Map to please me, I will re-take it to please you: & I beg to assure you that I never was in the habit of taking my friends to subscribe to any of my literary works ... My plan has been to exert myself to produce something good – useful – or beautifull [sic] – lay it fairly before friends & foes – & submit to chance. For some time past I have lost on all speculations. On this Map I am minus above £150.27

This note accompanied a copy of Britton’s 1835 volume on Worcester Cathedral, the last in a national series to be published before unsold copies were auctioned off.28 The series had been brought to a premature end by the high costs and declining sales that affected many such publications, as well as, Britton complained, by a lack of ‘liberal encouragement’ from cathedral authorities, not just over access to the buildings and archives but in purchasing the volumes. Britton signed off the volume on Worcester and the series with a thirty-two page preface (over a third of the volume) on the public spirit of his literary achievement, noting that he had sent a ‘printed address and respectful letter’ appealing for subscriptions to ‘forty-four prelates, and deans and chapters: to which the Author receive only six replies’, only one of which (Norwich) agreed to buy the whole series.29 ‘Read its preface,’ Britton told Constable, ‘that you may judge between me & Bishops.’30

Britton and Constable’s public lectures

In the 1830s Britton and Constable both joined in with the movement for giving public lectures at new institutions founded across England to diffuse knowledge to a wider population, with Britton lecturing on the history of architecture and Constable on the history of landscape painting. The lectures were held in urban centres and suburbs, mainly in the south and west of England, with Britton lecturing in London, Islington, Richmond, Kensington, Bath and Bristol, and Constable in London, Hampstead and Worcester. Britton published one of his lectures and substantial passages from others were recorded in Arnold’s Magazine of the Fine Arts.31 There were only brief newspaper reports of Constable’s lectures until Leslie reconstructed them from notes in his Memoirs.32 Both lecture series put forth progressive, urban-based histories in which examples of art and architecture from the past were both located in their period and place and formed landmark stages in a prophetic advance to a northern European Protestant present. While they pointed to periods of decline and revival, overall the story was one of progress towards the virtues of empirical investigation, scientific understanding and philosophical utility.

Britton’s lectures on the history of architecture were undertaken to earn money as well as to educate a broad public, even if the cost of illustrations used up much of his fee. He mainly lectured in and around London, Bristol and Bath, cities in which he had close personal connections and on which he published work.33 During the speculative boom that preceded the financial crash of 1825, Britton sent a letter to the Gentleman’s Magazine inviting subscriptions for a ‘novel plan’ uniting ‘amusement and instruction’ to tour West Country towns, including Bristol, Bath, Devizes and Salisbury; the Druidical Antiquarian Company would exhibit models and pictures ‘to be elucidated by lectures’ combining ‘something of the principles of the Cosmorama, Diorama, Panorama and Eidophusikon’.34 The plan did not materialise – perhaps another victim of the financial crash – but it indicates how Britton’s public lectures were staged as dramatic performances combining showmanship and scholarship.

In October 1833 Britton delivered lectures at the Bristol Institution in the wake of the burning of the city by Reform rioters, in which the cathedral caught fire but escaped destruction. Britton observed that ‘This city has recently been visited by a distressing scourge, which is not so ruinous as that which had burned the famed Italian city of Pompeii, yet was frightful and calamitous in its operations and ruinous in many of its results.’35 Britton trusted ‘the consumed parts of Bristol may spring forth from ruins, invested with all the attributes of utility and beauty’, notably through engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s projected railway and suspension bridge. Britton’s progressive history traced lessons from the cities of antiquity, illustrated by dramatic scenes in prints by John Martin, notably his print of the destruction of Nineveh (see The Fall of Nineveh 1829, British Museum, London). Britton also reported seeing Martin working on a painting that depicted the city of Jerusalem, with the scene of the Crucifixion outside its old walls; for an audience versed in New Testament prophecy, such as Britton’s would have been, this would have symbolised the turning point in history that heralded the New Jerusalem to come.36

One of Constable’s notes to Britton is addressed to John ‘Bristow’, the antiquarian name for Bristol, perhaps a slip in light of Britton’s many works on the city.37 Britton sent Constable one of his Bristol lectures on the subject of the Great Western Railway, in the form of a pamphlet that the company used to promote its founding and construction. The ‘rail-road’ was the latest episode in Britton’s progressive history The Road-Ways of England.38 Thanking Britton for the pamphlet, Constable replied: ‘On a title so forbidding who would have expected so interesting, so poetical (though true) a result … you have shown the subject … to be one of the greatest interest – and of the utmost importance.’39 The note goes on to praise Britton’s letter in the Times that developed a theme of his Bristol lectures in which he campaigned for the collection and study of Egyptian antiquities as a public national priority, to excite interest in ‘the amazing ruins of temples, palaces, and cities’ and advance ‘the higher department of archaeology’.40 Constable wrote: ‘I am anxious to call upon you and bring with me my two boys, who show, I am happy to say, a love of science and art … a visit to you & your home would be an epoch in their lives to be recollected in after life.’41 He added his response to a lecture that both he and Britton attended that was given by William Hosking, an antiquarian-minded architect and civil engineer who would go on to collaborate with Britton on the restoration of Bristol’s church of St Mary Redcliffe. Constable noted that Hosking’s ‘motives when he ventured to differ from you in opinion were mistaken by his hearers. But he was honest and well bred in what he said ... & I heard him with great attention.’42

Constable’s own lectures were largely delivered close to home, in Hampstead and at the Royal Institution in London, as well as further afield in Worcester. The Royal Institution was London’s leading venue for the public understanding of science, made famous by the theatrical presentations of chemist Michael Faraday, who taught Constable’s son. The lectures are framed in terms of successive ‘epochs which mark the development, progress and perfection’ of the landscape art produced in a series of major cities, notably Rome, Venice and Antwerp, before London took up its role in advancing landscape art. As a result, that art became part of ‘natural philosophy … a pursuit legitimate, scientific and mechanical’, as Constable described it in an attempt to secure scientific authority.43

The progress of knowledge was also devotional, as Constable put it in the final Hampstead lecture, in which the tone becomes increasingly scriptural: ‘a knowledge and love of the works of our Creator leads us to him’.44 Constable was well prepared with notes and illustrations, prints, drawings, sketches, which he labelled ‘specimens’ like the plants and minerals of scientific lectures, suggesting that he was concerned about his delivery. However, he was assured by one mentor, the surgeon George Young, that he could ‘command [his] audience’.45 In 1835 Constable was invited to reprise his Hampstead lectures at the newly formed Worcester Literary and Scientific Institution. ‘They are fully expecting me with my sermons,’ he confided to Lucas. ‘[W]ho would ever have thought of my turning Methodist preacher, that is a preacher on “Method” – but I shall do good, to that art for which I live.’46 Constable also included some autobiographical material in the lectures: ‘an ingenious account of his origin, and early occupation as a miller’.47

The theme of personal progress extended to the lectures’ reception. An official factory inspector reported to the government Select Committee on Arts and Manufactures that operatives attending Constable’s Worcester lectures in October 1835 treasured ‘great profit to themselves, as tending to correct their taste and improve their judgement’.48 Constable complained that the lectures were reported in the local Worcester press ‘mangled and mixed up’, although he conceded that ‘it was all well meant and not inelegantly done’.49 He remarked further on the energy and enthusiasm of the lectures’ audience, which was drawn from the commercial and industrial population of the city, contrasting this with the Cathedral’s clerics: ‘things which would advance intellect are paralysed and chilled by the drones of the Cathedral … it is so in all Cathedral towns’.50

Britton’s Salisbury

Britton and Constable were among a number of nineteenth-century artists and authors, including Turner and Charles Dickens, to focus on Salisbury in the county of Wiltshire, and both decisively shaped the image of the cathedral city. They each had personal motivations to focus on Salisbury – Britton was a native of Wiltshire and Constable a close friend of the Bishop of Salisbury, John Fisher, and his nephew, Archdeacon John Fisher. Furthermore, they each, in their different ways, represented the place of the cathedral in the development of the surrounding landscape of the city and country, and in the wider context of political and religious history.

Salisbury attracted wide attention because of the spectacular sight of its towering cathedral, affording a range of views in and around the city; its soaring spire was also visible for many miles across the countryside. Moreover, key periods in the history of Salisbury were strikingly visible in the landscape. These included the dramatic contrast with the abandoned hilltop site of Old Sarum, the former site of the cathedral before the city moved down into the valley in the early thirteenth century. There was also a more recent episode of renewal: the redevelopment of the interior and environs of the cathedral itself in the later eighteenth century, which involved clearing away a good deal of its medieval, Catholic fabric and fashioning a more modern-looking, conspicuously Protestant appearance. While Salisbury grew more slowly, over a longer period, than many larger and more conspicuously commercial and industrial towns, the very presence of a cathedral at the centre of a diocese – the area covered by the Bishop’s jurisdiction – made Salisbury a city by administrative definition. The diocese of Salisbury was extensive, ranging beyond Wiltshire, as far as the Thames Valley and including the royal palace of Windsor Castle, where the Bishop had an official residence named Salisbury Tower. As well as a religious centre, the city of Salisbury was also significant commercially, particularly for the region’s woollen and cloth economy; it undertook many administrative functions for the county; and it attracted a growing international tourist trade for nearby attractions such as Stonehenge as well as the Cathedral and Old Sarum. As an urban landscape Salisbury offered a vivid arena of larger social and cultural relations which preoccupied nineteenth-century observers, between the realms of the sacred and secular, the urban and rural, the ancient and modern.51

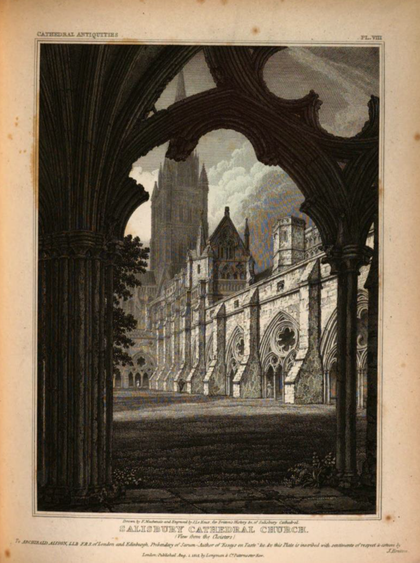

Fig.3

John Le Keux after Frederick Mackenzie

Salisbury Cathedral Church (View from the Cloisters) 1814, published in John Britton, The History and Antiquities of the Cathedral Church of Salisbury, London 1814

Britton put his signature on Salisbury with the first two volumes of The Beauties of Wiltshire (1801). Although he was a north Wiltshire man himself, he grew up beyond the diocese and had little religious upbringing apart from some time at a Baptist chapel school. He had never visited Salisbury before he made a walking excursion from London to do so for the book, nor had he set eyes on any cathedral apart from St Paul’s in London. Salisbury Cathedral (built 1220–1320) was the first subject he drew, recalling that ‘Often I have reflected on this scene and event’ and the ‘astonishment at seeing afterwards a tolerably executed engraving from the sketch I made’.52 The success of The Beauties of Wiltshire launched Britton’s career, leading to the nationwide, county-by-county work The Beauties of England and Wales, and two higher quality series on architecture and antiquities. These included The Cathedral Antiquities of England and Wales, which was characterised by collaborations with writers and artists, beginning with a volume on Salisbury Cathedral that featured the work of draughtsman Frederick Mackenzie and engraver John Le Keux (see Salisbury Cathedral Church (View from the Cloisters) 1814; fig.3).

Britton’s letterpress for the Salisbury volume, which was titled The History and Antiquities of the Cathedral Church of Salisbury and published in 1814, represents the cathedral as a spectacular force for progress.53 A key figure in the narrative is Bishop John Jewel, the Bishop of Salisbury from 1559 to 1570. Britton employs mythical meteorology to dramatise Jewel’s place in the annals of enlightenment: ‘On the accession of Mary to the throne, the religious horizon was overcast; a storm soon gathered, and the thunders of persecution and lightnings of intolerance and bigotry, burst forth on the nation.’54 Returning from exile on the accession of Elizabeth I, Jewel published Apologia ecclesiae Anglicanae (Apology of the Anglican Church) in 1562, a famous defence of the Church that Britton describes as an expression of a ‘liberal and luminous mind’, ‘translated into several languages and circulated all over Europe’.55 The main manifestations of Jewel’s ‘attachment to learning and literature’ were the ‘the act of building a library over part of the cloister’, starting a school, preaching, ‘visiting various parts of his diocese to instruct and admonish his inferior clergy’, and carrying out episcopal and civil duties far and wide in the West Country, as a commissioner for the Crown, ‘to root out Catholic prejudices, and establish Protestant doctrine’.56 Unlike Popish prelates, Jewel was not commemorated in Salisbury Cathedral by a conspicuous, elaborate tomb, but by a barely marked gravestone.

Britton’s characterisation of Jewel as saviour of the church is echoed in descriptions and illustrations of later improvements to the cathedral, ones that remained controversial in Britton’s day. It had been remodelled by James Wyatt in 1789–92, including the use of Joshua Reynolds’s design of Christ’s Resurrection for the east window above the open choir and chancel. This chimed with Britton’s description of Jewel: ‘As the sun in a spring morning, rising above the eastern horizon, is often obscured by clouds and mist, but gaining strength in its course dispels the gloomy and deleterious vapours, and gives life, light and joy to the human race – so Jewel rose in the western world ... a true Christian and a good man.’57 Britton was also careful to celebrate the current Bishop John Fisher, to whom the volume is dedicated. He secured a view of the Chapter House from the drawing room of the Bishop’s Palace for an illustration, and praised Fisher’s taste in directing improvements to the grounds for their ‘picturesque effect, their lawn, walk and canal, interspersed with large elm, ash, and other indigenous and exotic trees’ – features that characterised Constable’s views of the cathedral.58

Britton was keen to identify the cathedral as national public monument. Moreover, the cathedral had a larger significance, as an index of civilisation itself. Britton noted that it would not

require a great stretch of imagination, to deduce from this subject a philosophical and critical history of man in remote times; and as he appears to have been influenced by tyranny or liberty, by superstition and freedom … looking beyond the surface, or mere forms of buildings, let us endeavour to ascertain the condition, customs, arts and characteristics of the men who designed and raised them.59

Such reflections opened up cathedrals to wider appreciation, placing them beyond particular ecclesiastical, antiquarian or architectural expertise. Britton also recognised that their dramatic impact on visitors was ecumenical, appealing to people of many religious and spiritual persuasions as a sublime aesthetic experience. His Salisbury volume invites the visitor ‘to analyse his emotions, after first viewing this noble pile’ and its various effects at different times of day.60

A commercial and critical success, Britton’s volume on Salisbury Cathedral triumphed over the kind of adversity he would come to encounter when producing subsequent volumes on cathedral towns, namely the indifference or obstruction of cathedral authorities. Having advertised his volume on Salisbury, he discovered that the verger of the cathedral and author of its guidebook, William Dosdworth, had decided to produce a rival work, requisitioning a local historian whom Britton had hoped to take on board himself, and enlisting Britton’s main draughtsman, Frederick Nash. Published in Salisbury by the author and a small firm, Brodie and Son, Dodsworth’s volume was finished before Britton’s, which was issued by Longman; but their enmity lessened because they reckoned that the market for cathedral publications was expanding so rapidly, locally and nationally, that a competitive rivalry would benefit both. It turned out, however, that the verger had overreached himself: he incurred sizeable debts in production and was left with a large stock.61 In letters between Constable and his Salisbury friend Archdeacon John Fisher, Dodsworth’s fate is found to typify the stupidity of many cathedral officials, although the painter told another correspondent that he had consulted Nash’s illustrations for Dodsworth’s volume to depict details of the cathedral tower in his own work.62

Despite the success of his volume on Salisbury, Britton struggled to sustain the series of individual volumes on English cathedrals, particularly after the financial crash of 1825. He nonetheless endeavoured to widen the public’s awareness of cathedral cities as a type of urban landscape. He employed watercolourist George Fennell Robson to supply at least thirty drawings for his Picturesque Views of the Cities of England, published in series from 1826 to 1827, then in a single volume in 1828. The collective impression of Robson’s views is one of cathedral cities as robustly flourishing places that integrated wider landscapes – a contrast and a reproach to the turbulent financial environment in which they were published. The drawings position cathedrals at the centre of productive environs, including new bridges, warehouses and vessels in the City of London, smoking factories at Bristol and Chester, and traffic-filled turnpikes, hay fields, water meadows, laundry grounds and cattle paddocks in various places.

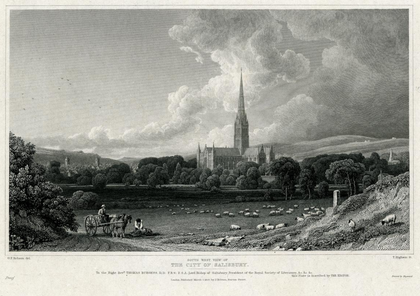

Fig.4

Thomas Higham after George Fennell Robson

South West View of the City of Salisbury 1827, published in John Britton, Picturesque Views of the Cities of England, London 1828

Etching

226 x 302 mm

British Museum, London

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The engraving of Robson’s South West View of the City of Salisbury (fig.4), for instance, is dedicated to the new Bishop of Salisbury, Thomas Burgess. As well as being known personally to Britton as president of the Royal Society of Literature, Burgess was a reforming figure known for his evangelical preaching, his promotion of improved agriculture and veterinary science in the neighbourhoods of cities, and for advocating for the abolition of slavery. The print’s ‘south west view’ from Harnham Hill shows ‘rolling clouds’ of the specified ‘effect’ that suggest a storm is receding eastward over the downs.63 A raking sun highlights the cathedral, picking out the detail of the west front along with the towers of the other churches in the city and suburbs, linked by the luminous line of a waterway. A cart waits to pick up a bale of hay that looks to be one of the last cut from the Harnham Water Meadows before sheep are pastured there. This was an advanced system of design and management, with drains and irrigation channels as well as carefully timed use and activity. Sheep safely graze for the day on the rich grass in the shelter of the cathedral church before being folded for the night on the surrounding chalk hills, and in future shorn for their fleece to supply the cloth industry.64

Fig.5

J.C. Varrall after W.H. Bartlett

Salisbury, View in Castle Street Looking South 1829, published in John Britton, Picturesque Antiquities of the English Cities, London 1828–30

Engraving

172 x 212 mm

Britton’s project on cathedral towns expanded with another illustrated work entitled Picturesque Antiquities of the English Cities (1828–30). The great majority of designs for this volume were drawn by a young apprentice, W.H. Bartlett, who was Britton’s favourite draughtsman due to the speed at which he worked and his range of knowledge: as Britton noted, Bartlett was ‘particularly inquisitive about maps, travels, voyages, geography and even Paterson’s and other road books’.65 Bartlett situated cathedrals within bustling urban scenes, streets thronging with traffic and people of all kinds, from tradesmen to tourists and church-going families, all bright and beautiful in a spirit of reformed Anglicanism. The views feature three of the main streets of the city’s spacious grid, ‘calculated to admit light and air’, with vistas of the cathedral on market day (see, for instance, Salisbury, View in Castle Street Looking South; fig.5).66 Such views are the result both of documentary records created during visits and of recollections and projections. Britton’s letterpress for Salisbury is closely aligned with Bartlett’s engravings of it in the way that it projects the place as a model city, one well planned as a spacious place in medieval times and a continuing example to congested, smoke-choked cities of the modern era.

Constable’s Salisbury

Constable literally put his signature on Salisbury, carving into the cathedral’s outer walls the inscription: ‘John Constable, East Bergholt, 1813’.67 This was common practice for tourists at the time, though Constable’s inclusion of his native Suffolk parish may have been intended to indicate a particularly close affiliation with Salisbury. The letterpress for the print of East Bergholt in Constable’s English Landscape notes that the artist first met the future Bishop of Salisbury, John Fisher, when Fisher spent summers at nearby Dedham as part of the rectorship of the village of Langham. Constable describes this as ‘the foundation of a sincere and uninterrupted friendship’ and a time that ‘entirely influenced his future life’.68 Constable secured the patronage and friendship of both the Bishop and his nephew, also named John Fisher, who served as his uncle’s chaplain and archdeacon of Salisbury Cathedral. As such, while he was a Suffolk man, Constable was probably more at home in Salisbury than was Britton, a Wiltshire man – at least within the precincts of the Cathedral Close, where the clergy were housed.

Archdeacon Fisher’s appointment to his uncle’s chaplaincy, along with many other lucrative offices, was the kind of preferment that earned him an entry in The Extraordinary Black Book, a radical attack on the ‘measureless rapacity’ of the clergy published by the writer and journalist John Wade in 1831.69 In his correspondence with Constable, Fisher bemoans the threat of religious reform to the ‘liberal, literary & learned body’ of the Anglican Church, while showing awareness that it had grown ‘fat’ with good living and lazy in its learning as well as preaching. Both men were scornful of cathedral officials more devoted to food and drink than literature and art, who gave the clergy a bad reputation.70 The very heritage of the Anglican Church seemed more valued in the United States, with Fisher observing that: ‘All the old folio divinity ([authors] Tillotson, Stillingfleet &c &c) is bought up for America & is not to be had now at the booksellers but at an enormous price’. Moreover, Fisher observed that the American author Washington Irving had done justice to the character of the clergy in Tales of a Traveller (1824), which ‘gives a pretty picture of the serene tranquillity and decorum of a Cathedral city’.71

Fig.6

John Constable

View of Salisbury c.1820

Oil on canvas

350 x 510 mm

Musée du Louvre, Paris

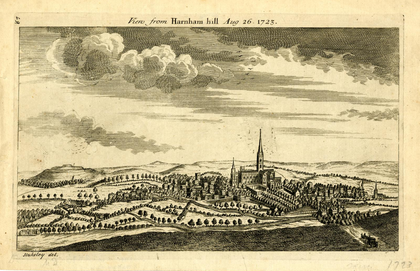

Fig.7

After William Stukeley

View from Harnham Hill Aug 26. 1723 c.1723

Etching with some engraving

176 x 279 mm

British Museum, London

© The Trustees of the British Museum

In pencil and oil sketches executed around 1820, such as View of Salisbury (fig.6), Constable depicted a popular view from Harnham Hill over the Avon valley that was familiar from topographical descriptions and prints (see, for instance, the print after William Stukeley’s View from Harnham Hill Aug 26. 1723; fig.7). Constable’s sketch shows the cathedral and its large close by the meadows, the buildings of the city, and the extensive deserted hilltop ramparts of Old Sarum. The story of the scene was spelled out by Britton as follows:

SALISBURY, or NEW SARUM, is a City of peculiar interest and importance in the topographical annals of the county and of England … It appears from ancient documents, and also from historical evidence, that when the religious community of Old Sarum deserted their former habitations … they fixed upon the spot as the most eligible for the erection of the new Cathedral. And for the foundation of a new City … Soil, water, and climate, with easy modes of social and commercial communication … Its situation is a broad vale near the union of three rivers; the Wily, the Avon, and the Bourne. The soil of this vale is a fine black mould, lying on a substratum of gravel, which forms dry and firm foundations for the buildings ... In addition to these natural advantages Salisbury is distinguished by an artificial arrangement ... All the principal streets are laid out at right angles to each other, and through each is conveyed a perpetual stream or channel of water … This peculiarity of position, and aquatic accommodation is, perhaps, unparalleled in this country, conducive to healthfulness, and convertible to many useful and important purposes in a manufacturing town.72

Many of Constable’s depictions of Salisbury are focused on the Cathedral Close and the riverside meadows, with a less conspicuous connection to the city at large than is seen in many other pictures of the place. For instance, they contrast with the drawings that Turner made under the patronage of Richard Colt Hoare in c.1797–1800 that address the construction and reconstruction of many spaces in Salisbury, including streets and buildings.73 They also differ from the engravings in Britton’s publications, which present the interior vistas of the cathedral itself while also placing the Cathedral Close in the wider landscape of a busy commercial city.74

Fig.8

John Constable

Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Ground 1823

Oil on canvas

876 x 1118 mm

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

One view in particular, from the Bishop’s garden, long defined Constable’s Salisbury: his painting Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Ground (fig.8). Commissioned by the Bishop for his London residence, it was Constable’s main exhibit at the Royal Academy in 1823, and was widely reviewed, before being shown again at the British Institution the following year.75 While the fact of its commission confirms the personal associations of the artwork, the scene itself was one familiar from a multitude of engravings and descriptions, including those published in Britton’s volume on the cathedral in which he celebrates the Bishop’s picturesque improvements.

On the left of Constable’s composition the Bishop and his wife walk down the garden path, past one of the conduits from the fish ponds, with the prelate pointing to the cathedral, as if acting as the viewer’s guide. There is nothing grand about the figure of the Bishop; he is dressed like any cleric out for a walk through the garden across the meadows to the church. Nevertheless, the inclusion of the Bishop’s portrait is a key feature. When Archdeacon Fisher suggested to Constable he make a print of the picture, he advised him to add letterpress stating that it was ‘from the original in the possession of the Bishop of Salisbury’, since this would make it ‘sell well at Salisbury’ as the Bishop ‘is as often a brand as a luminary’.76 In its review of the painting the London Magazine included a reformist note of its own, stating that if ‘the cathedral perhaps does not appear of sufficient magnitude … the landscape and cows are extremely well managed [and they] speak of that rich fat country ever to be found about the church’.77

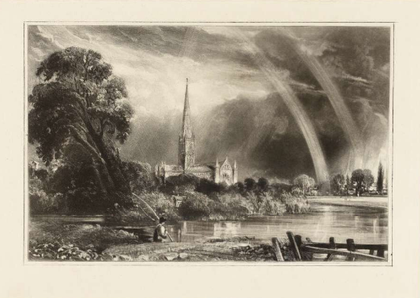

Constable’s most famous picture of Salisbury is Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1831. According to Leslie, the artist considered this painting ‘as conveying the fullest impression of the compass of his art’.78 Much has been written on the painting’s making and meaning, revealing its rich display of knowledge and association and its allusions to portrayals of places well beyond Salisbury, including Suffolk and Hampstead.79 Fisher referred ominously to the painting’s subject as a ‘Church under a cloud’ when Constable was making preliminary drawings in 1829.80 Yet it became less so when a rainbow was added to the painting before it was exhibited in Birmingham and Worcester in 1834, and with the addition of the title Summer Afternoon – A Retiring Tempest.81

Fig.9

David Lucas after John Constable

Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows 20 March 1837

Etching and mezzotint

550 x 688 mm

Royal Academy of Arts, London

Photo © Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photographer: Prudence Cuming Associates Limited

David Lucas’s print after the painting is brighter still and more serene in its final published state (fig.9). The dark clouds overhead have receded, no lightning now flashes by the spire, and the eponymous rainbow arcs more conspicuously over the meadows and along the watercourse. In the painting a rainbow appears to end at Leadenhall, Archdeacon Fisher’s house, possibly as a memorial following his death on 25 August 1832 – although the house was esteemed publicly as a historical monument to Elias of Dereham, who oversaw the original construction of the cathedral and perhaps designed it. In Lucas’s print the rainbow alights on the meadows, now grazed by a flock of sheep, tended by a shepherd alongside bales of newly cut hay. In correspondence with Lucas, the artist focused attention on profane as well sacred features in the landscape: a note from Constable demands: ‘Trees about the “arse end” of the waggon much put down ... also about the gardener’s “shitten house”.’82 The proportions of the print are less symmetrical than those of the oil painting, even though there is still a high degree of spatial compression and optical distortion compared with contemporary maps of Salisbury. It is as if the viewer of this print is looking through a lens at a 180-degree panorama, taking an imaginative excursion around the place and its surroundings, and absorbing various features of the landscape.

Publishing English Landscape

Constable consulted Britton and his work in the production of English Landscape due to the latter’s long experience in publishing illustrated works, as well as his knowledge of the Wiltshire subjects of Salisbury, Old Sarum and Stonehenge. The artist was conscious that the style of mezzotint engraving employed by Lucas was more darkly dramatic than illustrations of Britton’s works, even where Britton’s engravings displayed pictorial effect as well as factual documentation. Sending Britton the first number (or part) of English Landscape, Constable confessed that he would be ‘much flattered if you think well of it’, since ‘I need not tell you that my first object with these things is to attempt the “chiar’oscuro” of nature’.83 Constable told Lucas a few days later that ‘Britton just wrote to me saying we are too black – he is too white’.84 Replying to Britton, Constable was more circumspect about the darkness of the engravings: ‘you are quite right in cautioning me ... my friend Lucas was a pupil of [Samuel William] Reynolds’s – and I am knocking Reynolds’s black fog out of him as fast as I can’.85 He went on to suppose that the prints may have been

rendered too ferocious being without color. Still I should be insipid without it – and your view of middle tint is equally applicable to your style of subject, namely a delicate rendering of the parts, &c … I thank you at all times for your hints, tempered as they always are with good nature and good sense.’86

After disappointing sales of the first edition of English Landscape in 1830–2, Constable planned a second, cheaper edition with more substantial commercial promotion.87 Such promotion was standard practice for Britton, who was renowned for publicising and puffing his own publications, although Constable confessed to Lucas that he found it ‘disagreeable’, ‘disreputable’ and lowering to the ‘trade’, especially given that it involved spending even more money.88 Engravings for the second edition were issued in 1833, to be followed by letterpress that more fully explained the style and subjects of the engravings. As Constable wrote to Leslie in January 1834 when he sent him specimens of draft texts, ‘many can read print & cannot read mezzotint’.89 In February of that year Constable told Britton he was planning ‘a page of letter press to each plate – containing observations on Art, and a description of natural phenomena &c &c’.90

Constable planned to extend English Landscape with an ‘appendix’ in which he published unused designs. In a note to Britton of early 1834 Constable says ‘we are looking for you here with some anxiety and much hope’ and explains that he wishes to make English Landscape ‘more complete to leave as /(fragile)/ property for my children’.91 To do so, Constable enlisted the assistance of the draughtsman Robert Billings, who had just completed an apprenticeship with Britton. The choice of Billings is significant: he was esteemed for his architectural drawing and design and would go on to illustrate publications by Britton on London churches and the buildings ruined in the 1834 fire at the Houses of Parliament.92 Among the subjects to be included in Constable’s projected appendix were Salisbury and Stonehenge. The view of Stonehenge was a ‘poetical one’, Constable told Britton, since ‘its literal representation as a “Stone Quarry” has been often enough done’.93 Based on a composition from Colt Hoare’s The Ancient History of Wiltshire (London 1810–21), Constable’s view of Stonehenge shows the monument from a distance at sunset with a carriage speeding past it on the road, recalling Constable’s comment on Britton’s pamphlet on the subject of ‘road-ways’: ‘so poetical (though true)’.94

The appendix was not published in the end, and just four of the twenty-two engravings in the second edition of English Landscape were supplied with printed letterpress. These four letterpresses built on various precedents for print series of this kind: they followed the example of older publications like the Copper Plate Magazine (published 1792–1802) in having a page of letterpress facing an engraving. However, Constable’s text offers much more content, going beyond descriptions of a place and the occasional poetic quotation to include observations on the art of their portrayal. They resemble the essays that Britton wrote or commissioned for his works, although unlike Britton’s they are kept to one page rather than extending over a series of pages. The texts are also unlike the letterpress of most prints series in that the artist authored them himself, drawing on a range of sources. They consist of passages largely in Constable’s own words on the subject of his art, with echoes of his lectures, combined with sections that use, or are based on, the words of others, including personal letters as well as published works. He used various forms of paraphrase and quotation, some silent (not indicated as quotations) and modified; as a result the texts are eclectic, splicing subject, style, expression and register.

The structure of the texts is clearly set out, with an evident distinction between paragraphs of Constable’s observations on art, on painting and mezzotint, and ones that describe places, their history, geography and meteorology. The letterpress forms a finely composited page in terms of typography, inking and layout, with carefully placed paragraphs, indented passages of verse and italicised and capitalised quotations. While the mezzotints have been reproduced frequently, it is remarkable that the accompanying letterpresses have not, but rather are transcribed into modern type that spills over two pages.95 This is unfortunate given that, as will be shown below, the letterpress texts are designed to be read alongside the mezzotints as part of a graphic whole, with a series of correspondences and translations between image and text.

Old and New Sarum

The pairing of Old and New Sarum was a key part of Constable’s plans for English Landscape, perhaps because the publication was to be dedicated to Archdeacon Fisher before his death in 1832.96 Constable was particularly painstaking with the engravings of both sites, and although the publication of the print of New Sarum was finally abandoned after a series of revisions as a proof, that of Old Sarum was published in two versions. In a note of July 1830 Constable told Britton that the second number of English Landscape ‘will contain “Old Sarum”. I could show you a series of drawings of the grand old fellow which would make a book.’97 Britton’s works include two main texts on Old Sarum, both of which informed the letterpress and the engraving in English Landscape. One is more schematic and expressive and appears in The Beauties of Wiltshire, and the other, which is more detailed and record-like, appears in the Wiltshire volume of The Beauties of England and Wales, which Constable owned and which he loaned to the engraver.98 While both of Britton’s texts undertake to sift facts from fancy and contrast measured views with marvellous visions, they also quote at length passages of ‘fanciful conjecture, and whimsical hypothesis’ and indulge in colourful anecdote and poetic enchantment.99

This was a feature of Britton’s accounts of other Wiltshire monuments like Avebury and Stonehenge, which were written in a dramatic style that combined topography and scenography, instruction and entertainment. While Old Sarum had a more settled, documented historiography, at least in its recent annals, it was a place renowned for its complex and contested history.100 One of Britton’s earliest published drawings was of Old Sarum – it was used to advertise The Beauties of Wiltshire – and he and his pupils returned to the site at regular intervals, despite the fact that Britton tended to illustrate his texts on the place with reference to the many prints made for other published works, including those by Stukeley and Colt Hoare.101

The very name of Old Sarum was provocative. It was shorthand for political corruption and known as the nation’s most infamous ‘rotten borough’. In 1831 its two Members of Parliament ran unopposed and were returned by five voters, none of whom lived in the borough, while populous industrial towns remained unrepresented. The moderately reformist Britton was careful to reframe radical views of Old Sarum, for ‘[radical reformist Thomas] Paine and many other zealous political writers have marked this place by their revolutionary anathemas’.102 Britton reports that visitors came to witness the five voters assembling by the urban ‘burgage’ plots they owned but did not live on, ‘said to be sites of the last houses … on the south-west side’ of the nearly ruined city of Old Sarum. He presents this event as part of the annals of a borough that ‘has long been a subject of popular notoriety’ but which played a foundational role in the establishment of parliament itself.103 Such is Britton’s moderation that he suggests reform is more a moral than political matter, since the corruption of parliament is ‘not so much in the possessors of purchasers of burgage tenures, as in the needy and unprincipled persons who thus sell their liberties and privileges … who first corrupt the sources of independence … [T]he most permanent and important political reform that can be adopted must commence with the people.’104 Britton took a long view:

Though a spot apparently desolate, and with scarcely a vestige of human habitation, [Old Sarum] is nevertheless peculiarly interesting to the topographer, and to the antiquary … to investigate and develope [sic] the history of former times, to display the progressive and fluctuating sate of towns and buildings at various eras, and to present to the readers imagination a picture of the manners and customs of our ancestors, as manifested in their public works, and popular pursuits. Contemplated in this light, Old Sarum must be as interesting to the English antiquary as the sites of ancient Troy and Carthage can be to the classical reader. It was one a proud, populous, and flourishing city, adorned with a Cathedral and other churches; and guarded by lofty bulwarks, towers and a castle; but now it displays nothing of human art, but ditches and banks, which are partly overgrown with wild brush wood, while the lower level and is appropriated to corn and grass.105

The engraving of Old Sarum in Constable’s English Landscape is a view from due south, one that displayed to best effect the symmetrical profile of the ramparts and citadel of the abandoned city. This elevation invited comparison with other architectonic views of Old Sarum, including circular ground plans (like that engraved for the archaeologically informed first edition of the Ordnance Survey map), and with imaginative reconstructions of the walled, towered city that could be found in the many popular guides to the place.106

In The Beauties of Wiltshire Britton framed the modern experience of Old Sarum as one of peaceful contemplation of a previously war-stricken region. Writing in wartime, when Britain was threatened with Napoleonic invasion, he observed that:

The military antiquary will find much to admire in its deep ditches, high ramparts and great extent; and the man addicted to reflection, and possessing sensibility, will feel interested in reverting to the tales of other times and derive pleasurable consolation from comparing them with the transactions of the present moment. What scene does this place, and indeed all Salisbury Plain present for meditation – when we contrast the warlike days of yore with the present days of domestic peace. Now, the humble solitary shepherd … now, the poor cottager … are alike secured by the laws of the land, from the ‘blood-stained soldier’ and ‘plundering tyrant’.107

The letterpress in English Landscape reframes the sentiments of this passage with quotations from prospect poems. It opens with a modified line from Oliver Goldsmith’s The Traveller; or, a Prospect of Society (1764), amending the poem’s simultaneous social panorama to represent a changing scene, and charting a history where ‘The pomp of Kings, is now the Shepherd’s humble pride’.108 The letterpress ends with a passage from James Thomson’s The Seasons (1730) that recalls the former history of a shepherd’s pasture, capitalising the lines that describe Old Sarum: ‘THE MASSY MOUND / THAT RUNS AROUND THE HILL, THE RAMPART ONCE / OF IRON WAR’.

Fig.10

John Constable

Letterpress for Old Sarum, from the second edition of English Landscape 1833–5

Fig.11

David Lucas after John Constable

Old Sarum (second plate) 1833, from the second edition of English Landscape 1833–5

Mezzotint on paper

150 × 223 mm

Tate

Two versions of Old Sarum were published in English Landscape: one in the first edition, and a revised version in the second edition. Constable was not satisfied with the first, in which ‘the mounds and terraces were not marked with sufficient precision’.109 In the second plate the viewer could trace the foundations of ‘former greatness’, as the letterpress put it, through the ‘vast embankments and ditches tracked only by sheep walks’, and could re-imagine the walls, castle and cathedral of ‘this proud and “towered city”, giving laws to the whole kingdom – for it was here our earliest parliaments on record were convened’ (figs.10 and 11). The drama of the second version of Old Sarum was enhanced by stormier weather effects. This was apt for a place ‘constantly torn by tempestuous winds’, in the words of a translated papal document of 1217 about threats to the fabric of the cathedral, which was quoted by Britton.110

Of the four printed letterpresses to the second edition of English Landscape, the one for Old Sarum creates a close correspondence between text and image, between the page of printed text and that of the mezzotint. The key quotation that Constable chose for his depiction of Old Sarum in both editions is from the Book of Hebrews, at the time attributed to St Paul the Apostle. It appears italicised in the letterpress in the Latin version from the Vulgate Bible, ‘Non enim hic habemas stabilam civitatem’, and in its English translation from the King James Bible, capitalised and italicised under the title of the engraving: ‘HERE WE HAVE NO CONTINUING CITY’. The Latin version was made famous in Constable’s time through the diary of John Evelyn, published in 1818, in which Evelyn used the quotation to describe London after the Great Fire in 1666, adding ‘the ruines resembling the picture of Troy: London was, but is no more!’.111 The English translation was much better known, as it had long been employed as a motto by all Protestant denominations, used in sermons, commentaries and grave inscriptions. It was quoted by Constable to one of his Hampstead circle, the schoolmaster Benjamin Dawson, in a note discussing Old Sarum: ‘Who can visit such a solemn spot, once the most powerful city of the West, and not feel the truth and awfulness of the words of St Paul: “Here we have no continuing city”.’112 The phrase was understood as prophetic since in full the biblical line read: ‘Here we have no continuing city, but we seek one to come’.113 The vision of the city to come was both a heavenly one, and, in the context of Salisbury’s history, an earthly one too, with the building of a new cathedral, and model city, below the ruins of the old.

The letterpress to Old Sarum tells of periods ‘involved in that almost impenetrable gloom, which clouds the dark history of our Middle Ages [and] ruthless acts of tyranny and deeds of violence perpetrated on this far famed mount’, which readers of Britton’s texts would have discovered included public acts of castration and eye gouging. Nevertheless, Old Sarum was a landmark for enlightened episodes of English history, ‘that great political event, the establishment of the feudal system’, and the ‘seat of ecclesiastical government’ which in ‘days of chivalry’ dispatched ‘valiant knights over Palestine’ as well as diffusing ‘the blessings of religion over the western part of the kingdom’. This all took place before the clergy made peace with the military by moving with ‘the most respectable inhabitants’ to build a new cathedral church as the foundation of Salisbury. The ‘last step’ in the desolation of the ‘once proud and populous city’ of Old Sarum was the building of the bridge at Harnham that ‘diverted the great western road, and turned it from the old through the new city’.114

Fig.12

David Lucas after John Constable

Salisbury Cathedral c.1831

Mezzotint on paper

178 x 247 mm

British Museum, London

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The ‘new “old Sarum”’ that was published in the second edition of English Landscape seems to have been a replacement for ‘New Sarum’, a view of Salisbury over the meadows. As mentioned, the plate of New Sarum was abandoned after a protracted process of revision over a dozen progress proofs. Two of these progress proofs, taken together, tell a story of New Sarum. The earlier one shows the cathedral in silhouette, its steeple in scaffolding after one of the many real and symbolic lighting strikes in its history. Yet the later proof shows the steeple repaired and the cathedral brilliantly lit after a passing storm, with a proverbial rainbow alighting on the meadows and clerical dwellings (fig.12).115 The urban history of Salisbury as projected in English Landscape is both a tale of two cities – Old Sarum and New Sarum – and a story of one, as the cathedral was moved from the old site to the new. It shows Salisbury as a continuing city, beset by changing fortunes; a city whose history extends to this day and is defined by its powerfully symbolic cathedral.