In the age of fly-on-the-wall TV, the skin of a person far away can seem closer than the face of my neighbour, making theatre appear outdated. Why should people cram themselves into theatres, side by side with strangers, breathing the same air and feeling the warmth of their bodies? A hit singer I heard on the radio this morning gave me a clue: “Theatre is more ‘real’; playing in public, with the public, that’s where it happens.”

To paraphrase Walter Benjamin: it’s because it’s become obsolete that the theatre is revolutionary today. To fight the “ludic illusion” denounced by the Situationists, some contemporary artists following different kinds of logic – consciously or otherwise – are using modes borrowed from theatrical form. For example, the filmic staging of Ulla von Brandenburg’s tableaux vivants connects with a tradition that was very fashionable in the eighteenth century, from the Kit Cat Club to erotic drawing-room games. She asks actors to pose as in an historic classical painting, adopting stereotypical attitudes and gestures, which are then photographed. This traditional pictorial arrangement taken by modern methods creates strange states of tension in the imagery: the set-up seems unreal, nothing happens and the characters appear to be waiting for something.

In many ways works by the Portugese artist Vasco Araujo, the metaphor of theatre is used to reveal the artificiality of social codes and conventions with which we are so familiar. He uses the voice, stage sets, curtains and mise en scène devices to create an architectural environment which often acts as a mirror image of our world, revealing what is obvious but hidden behind our veils (curtains) of these conventions. In Duettino 2001, a two-minute film loop, we see the artist as an actor playing the role of two characters, in this case a duet from Don Giovanni, though all is exaggerated – the make-up and costumes, the affected manners. In her chapter ‘Notes on a Camp’ in Against Interpretation, Susan Sontag explored this theatricality in relation to the idea of camp:

Indeed the essence of camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration…Though I am speaking about a sensibility only – and about a sensibility that, among other things, converts the serious into the frivolous – these are grave matters.

Theatrically, disguise and outrage are attributes of the camp sensibility. Resexualising the artistic elements is more than returning ‘savagery’ to art or demonstrating for the umpteenth time that the creative impulse draws on sexual roots. It means subverting the good conscience that smoothes the domestic universe, showing that behind the closed door of aseptic homes, reality outdoes fiction. So camp, in its use of exaggerated feminisation and distortion of habits and manners, reveals a part of what can often exist behind the stage – such as the perfect middle-class house as the artificial façade.

Ulla von Brandenburg

Der Brief 2004

Super 8 transferred to DVD, black and white, without sound

2 min 30 sec

Still frame

Courtesy Produzentengalerie, Hamburg, and Art:concept, Paris

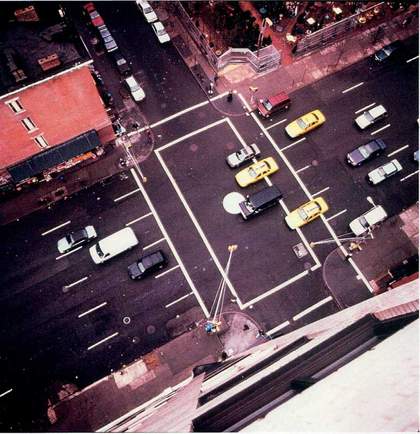

For some artists, the theatricality stems from the physical context of the work. Kirsten Mosher’s art often interrupts the way we move through and think about public space in the city. In Local Park Express 1998 she made a traditional baseball diamond on the busy intersection of a New York street.

Whereas Mosher’s work relies on people moving through the space, Rita McBride’s Arena turns whoever sits on the semicircular structure that resembles a makeshift seating area for an outdoor theatre into both the audience and the subject being viewed. Members of the audience are no longer passive, they are watching each other, exposed. In this she comes close to Bruce Nauman, who conceived a similar work. “People die of exposure,” says the first line of Nauman’s poem The Consummate Mask of Rock. To expose oneself is to reveal the artifice, the mask, not to unveil, but to indicate that there is an enigma. As Paul McCarthy says about his use of the video camera: ‘At one point the camera became the persona’ – or the device became the mask. In fact, in ancient Greek theatre that was the term used for the heavy stone masks whose mouths, with comical openings, acted as ‘voice-carriers’.

Kirsten Mosher

Ball Park Traffic New York, 1998

Paint, baseball bases

© Kirsten Mosher

In the world of fast images, the experience of looking has been reduced to the level of fame, but the theatre in all its manifestations (including the museum) can still feel like the ‘real thing’, the difference between history and news. The grotesque television stage of ‘real people’, actors of ‘fake dramas’, will never attain the degree of truth, of the sense of play, that you get with, say, Roman Ondák’s piece It Will All Turnout Right in the End 2005–6, for which he made a scaled-down version of Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. Here, the museum is the theatre, the place of action, creating a stage-set for viewers, providing a platform for fictions to unfold. This sidestep, this peripheral glance that comes to us from Joyce, and from which Breton made the Surrealist merveilleux, has an aftertaste of the “uncanny” dear to Freud and Mike Kelley.