Walter Richard Sickert

Off to the Pub (1911)

Tate

The decade leading up to the First World War was an exhilarating period for art in Britain, in London especially. In 1905 the Parisian dealer Paul Durand-Ruel brought to the Grafton Galleries the first substantial exhibition of the Impressionists seen in the capital. Five years later, in the same galleries, Roger Fry mounted the first of his two Post-Impressionist shows, introducing a bewildered public to Cézanne, Gauguin and van Gogh; in 1912, piling Ossa upon Pelion, he attempted to convert them to Matisse and Picasso. That same year Marinetti and the Italian Futurists launched their own noisy assault on London. This heady atmosphere invigorated a whole generation of young artists: manifestos were issued, magazines (including Rhythm and Blast) were started, artists’ co-operatives (the Omega Workshops and the Rebel Art Centre) were founded and exhibiting societies – many of which took their names from streets or districts of the city (the Fitzroy Street, Camden Town, Cumberland Market and Grafton groups) – proliferated. They did so in a frenetic, competitive environment, where jealousy was rife and quarrels furiously erupted. But the scene was, in fact, more fluid than many histories of this period suggest, with much fraternisation and overlapping interests. It was only with the awkward, ill-fated attempt, on the eve of the war, to unite all these cliques under the umbrella of the London Group that rival societies degenerated into bitter factions. At their helm were the three great animators of modern art in Britain: Walter Sickert, Roger Fry and Wyndham Lewis.

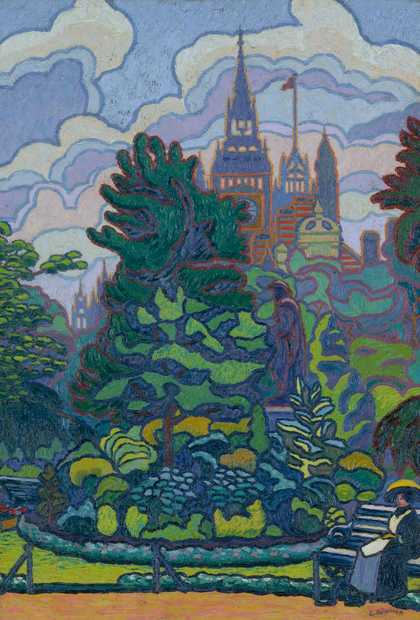

Charles Ginner

Victoria Embankment Gardens (1912)

Tate

The most senior figure in this triumvirate was Sickert, who since the mid 1890s had been the king across the water, living in self-imposed exile in Dieppe and Venice. In 1905 he returned to London – “sent from heaven to finish all your educations”, as he told one of his pupils, Nan Hudson. He did not go back to his old stamping ground in Chelsea, where Augustus John now ruled the roost, but sought out lodgings and studios around north London, renting two of the latter in Mornington Crescent and Fitzroy Street. One of nature’s actor-managers, he began to gather around him a group of like-minded artists, and in 1907, under the formula “Mr Sickert At Home”, he inaugurated the Saturday afternoon gatherings at 19 Fitzroy Street where these artists exhibited, and endeavoured to sell, their work to a small, but discriminating clientele of admirers and patrons. Sickert had by now repudiated the teaching of his first master, Whistler, abandoning tonal painting in favour of a more substantial paint surface and his own particular brand of anecdotal realism. “Taste is the death of a painter,” he declared in 1908. Two years later he delivered his famous elaboration of this dictum: “The more our art is serious, the more will it tend to avoid the drawing-room and stick to the kitchen. The plastic arts are gross arts, dealing joyously with gross material facts… while they will flourish in the scullery, or on the dunghill, they fade at a breath from the drawing-room.”

In 1911 the Fitzroy Street Group begat the more formal, and exclusive, Camden Town Group, formed in exasperation at the milk-and-water Impressionism that prevailed at the annual exhibitions of the New English Art Club. It was hardly a band of young Turks. Its two senior members, Sickert and Lucien Pissarro, were both in their late forties; Robert Bevan was only a year or two younger. Among its front rank were two of the outstanding painters of their age, Spencer Gore and Harold Gilman, but there were others who promised less. The group’s secretary J.B. Manson is better remembered now for a series of drunken misadventures during his disastrous tenure as director of the Tate Gallery than for his lacklustre exercises in English Impressionism; Walter Bayes, a protégé of Sickert, was at least as well-known as a prolific critic, author and teacher than as an artist. Two members were essentially amateurs: William Ratcliffe, a wallpaper designer from Letchworth who owed his inclusion to the patronage of Gilman, and John Doman Turner, a deaf stockbroker’s clerk from Streatham, whose artistic training was undertaken via a correspondence course with Gore. Several others, including Augustus John, Henry Lamb, J.D. Innes, Wyndham Lewis and (briefly) Duncan Grant, contributed to CamdenTown exhibitions, but added little or nothing to the group’s house style. Women, who had been welcomed into the Fitzroy Street Group and who were prominent in the Grafton Group (Vanessa Bell) and the Vorticist movement (Helen Saunders and Jessica Dismorr), were excluded from this all-male club.

Walter Richard Sickert

La Hollandaise (c.1906)

Tate

The Camden Town Group was so named, according to Bayes, because Sickert claimed that “the district had been so watered with his tears that something important must sooner or later spring from its soil”. It was, from the start, something of a misnomer. Only a handful of its members lived, or painted, in the area; and such a parochial label was anyway deceptive. French connections were as important as English sensibility. Sickert had first met Degas, his hero and mentor, in 1883; thereafter, he never lost an opportunity to advertise his friendship with the Frenchman by liberal quotation of the latter’s hardhitting mots in his conversation and his writings. Lucien Pissarro, whose influence over his younger friends was for a time considerable, had, of course, been born into the heart of the Impressionist revolution. Bevan had got to know Gauguin when he worked at Pont-Aven in the 1890s; and Charles Ginner, born in France to English parents, was already an advocate of van Gogh before he crossed the Channel in 1910. The impetus for Sickert’s return to London had been his meeting with Gore at Neuville, outside Dieppe, in 1904; and over the following decade Gore, Gilman, Manson and Doman Turner, as well as Sickert, all made regular painting expeditions to northern France.

Roger Fry’s Post-Impressionist exhibitions crystallised debates about the implications of modern French art. But whereas Cézanne, who Sickert dismissed as un grand raté (a great failure), was the lodestar for artists in Fry’s ambit, the Camden Towners tended to look elsewhere for succour. Under the influence of Pissarro’s Divisionist theories, several of them, Sickert included, had already begun to lighten their palette with spots and patches of bright, pure colour. Some went further: Bevan imitated the cloisonnisme of Gauguin, enclosing areas of dense impasto with thick outlines; Ginner and Gilman both developed the habit of laying on paint in a thick, lumpy mosaic that confirmed their admiration for van Gogh. Only Gore, however, was a whole-hearted Post-Impressionist in his release from naturalistic colour, his bold simplification of forms and his liking for geometric patterning. He had “the digestion of an ostrich”, wrote Sickert after Gore’s untimely death. “A scene, the dreariness and hopelessness of which would strike terror into most of us, was to him matter for lyrical and exhilarated improvisation.” He alone transcended the Camden Towners’ taste for the dull and the dingy. “Theirs is no vulgar provincialism,” commented Clive Bell, spokesman for the Francophile tendency, “but, in its lack of receptivity, its too willing aloofness from foreign influences, its tendency to concentrate on a mediocre and rather middle-class ideal of honesty, it is, I suspect, typically British.”

Bell’s analysis was acute, for in CamdenTown a fundamental question concerned not just how, but what, to paint. The typical CamdenTown picture is easily summarised: the shabby interior of a seedy north London boarding house, with a female nude either sprawled on an iron bedstead or rising from tousled sheets to attend to her toilette; the corner of a dreary street, often seen at an oblique angle from an upper-storey window; the stage, or audience, or both in the gilt-and-pasteboard world of the music hall and theatre. To this repertoire Sickert added his own, unique contribution: an updating of the long established conversation piece, in which two figures – clothed male and nude female, or a fully-dressed couple – act out some implicit but unexplained story about sexual relationships or the boredom and frustrations of married life, the ambiguity of their meaning exaggerated by the artist’s habit of giving these pictures interchangeable titles, so that a painting purporting to depict the notorious murder in CamdenTown of a casual prostitute, Emily Dimmock, becomes also a vignette of marital apathy and financial despair, What shall we do about the Rent? 1909. In fact, the range of subjects tackled by CamdenTown painters was far more diverse than this, and the emphasis on squalor can be overdone. Pissarro clung to the suburbs, painting quiet hymns to the grey skies of Hammersmith and Acton; Malcolm Drummond stuck to Chelsea, a less smart area then than today, filled with side-street pubs and second-hand furniture shops. The Utopian urban environment of Letchworth, the prototype garden city built in the middle of the Hertfordshire countryside, where Gilman and Ratcliffe lived and where Gore made some of his most adventurous paintings, of beanfields and cinder paths and the brand new railway station, was a world away from the dank and grime of north London. Camden Town painting encompassed the unspoiled verdant landscape of Devon, the timber yards and covered market of Leeds and the fjords of Norway. Occasionally, an air of seaside gaiety intruded.

Sickert’s moving obituary of Gore, written for the New Age, was headlined “A Perfect Modern”. The Camden Towners were indeed modern, but only up to a point. They shared none of the Futurists’ thrill at the speed and turmoil of contemporary life (though Gore may have been the first artist to depict an aeroplane), nor the Cubists’ ambition to shatter traditional perceptions of reality. They were antipathetic to abstraction and when, as an offshoot from Camden Town, Ginner and Gilman launched a Neo-Realist movement in 1914, they did so in the belief that, in the hands of Matisse and Picasso, art had become debased through its loss of immediate contact with reality. A poignant strain of nostalgia runs through much Camden Town painting: the horse-drawn cabs that Bevan lovingly commemorated were almost obsolete when he began to paint them in 1908, superseded by new motorised means of transport, and even the music hall was past its heyday. There were exceptions to this wariness about modernity, of course. Drummond, whose crisp, flat technique and audacious use of high-keyed colour was particularly well-suited to the celebration of modern life, delighted in new forms of entertainment – the cinema, American-style dance halls, even a celebrity trial. And Ginner enthusiastically recorded the brashness and bustle of the modern metropolis as motor cars and buses converged on Piccadilly Circus. But the Camden Towners’ modernity lay less in stylistic innovations, or in their choice of subject matter, than in their uncomplicated attitude to reality. They avoided the two fatal tendencies of so much previous English art, the urge to glamorise the rich or sentimentalise the poor; refusing to moralise, they presented a faithful, dispassionate account of the world around them, devoid of social or political commentary. Nowhere is this approach better exemplified than in the marvellous series of portraits that Gilman made of Mrs Mounter, his landlady in Maple Street, in which artist and sitter confront each other directly and no element of truth is spared.

* * *

As an exhibiting society the Camden Town Group was short-lived. Between June 1911 and December 1912 it held three shows, all at the prestigious Carfax Gallery in St James’s, before it was subsumed into the larger, more amorphous London Group. Thereafter, Sickert went his own way, while Gore and Gilman both died young – the former from pneumonia in 1914, the latter a victim of the Spanish flu epidemic that swept Europe at the end of the war – thus robbing British art of two of its brightest stars. As a term suggestive of a particular style of informal realism, Camden Town has enjoyed a longer currency, though its legacy has only intermittently been acknowledged.

Charles Harrison, no flag-bearer for the figurative tradition, has called the group “one of [the] century’s very few successful, modern, realist movements”. Sickert apart, however, its members have been short-changed by posterity. Few have been the subjects of solo exhibitions. Ginner, an artist of immense integrity notwithstanding the increasingly formulaic output of his later years, was last honoured by the Arts Council in 1953; Gore, scandalously for so scintillating a painter, has not had a museum show since 1955; Drummond, a consistently underrated figure, got his one and only outing in 1963. In the past 30 years only Gilman has been awarded a full-dress retrospective, though Bevan is to be given his due in exhibitions in Edinburgh and Southampton later in 2008. Remarkably, the group as a whole had to wait 65 years from its dissolution before its history was written by Wendy Baron, whose indefatigable scholarship has almost single-handedly revived its reputation. Tate Britain’s exhibition is the most comprehensive survey yet of Camden Town painting. Outside Britain, these artists barely register. An enterprising attempt was made several years ago to introduce them to a French audience with an exhibition, shown at Pontoise and Dieppe, of the work of Pissarro, Sickert, Gore and Gilman. But when in 2002–3 a wide-ranging assessment of twentieth-century British art, Blast to Freeze, was mounted in Germany and France, the Camden Towners were omitted en bloc.

Patrick Caulfield

Second Glass of Whisky (1992)

Tate

© The estate of Patrick Caulfield. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2026

And yet Camden Town stands at the head of a rich and healthy tradition. The whole course of modern English realism may be said to flow from Sickert’s exhortation to his followers to flee the drawing-room and adhere to the kitchen. The conventional history of twentieth-century art in Britain follows a linear progression, tracing an ongoing dialogue – at times robust, at others overly polite – with first European and then American Modernism. But this version of the triumph of Modernism overlooks the evidence that in Britain much of the most vital and radical art has actually been produced by those who have continued to explore a native figurative or realist vein.

The two realist movements that flourished either side of the Second World War owed an explicit debt to Camden Town. At the Euston Road School – its very name, coined by Clive Bell, carrying an unmistakable echo of its north London ancestor – artists committed themselves to direct, objective observation of modern life and Sickert was accorded the status of patron saint, his practice of reasserting the grid of his preparatory, squared-up drawing on the final canvas becoming one of the school’s most distinctive mannerisms. The Kitchen Sink School – promoted at the Beaux Arts gallery run by Helen Lessore, the sister-in-law of Sickert’s third wife, its name likewise redolent with Sickertian reference – turned its back on tastefulness and ornament, with deadpan depictions of a city still threadbare from rationing and privation. There are, too, distinct affinities with Camden Town among the painters who make up the so-called School of London. Leon Kossoff has haunted the city’s railway bridges and sidings, much as Gore and Pissarro did a century ago, and no artist has stalked Sickert’s territory so obsessively as Frank Auerbach. Sickert hovers above Auerbach’s north London landscape, as tangible a presence as the chimney of the old Carreras cigarette factory looming over Mornington Crescent, or the statue of the Liberal politician Richard Cobden (Sickert’s first father-in-law) standing outside Camden Palace. Even Francis Bacon, an artist usually considered immune to local influence, absorbed something of Sickert’s hard-bitten outlook in his frank portrayal of naked models on isolated beds.

Allusions abound to the iconography of Camden Town in the work of subsequent English realists: in Graham Bell’s interior of a café in Goodge Street, an illustration of a slice of monotonous life to compare with Ratcliffe’s fly-blown eating house in Finchley; or Claude Rogers’s Cottage Bedroom 1944, in which a plumpish female model is seen end-on lying on an iron bed; in the precocious Derrick Greaves’s Gilman-esque drawing, made when he was just fifteen, of a kettle coming to the boil on a humble kitchen stove; or Auerbach’s apparently unconscious revision of Sickert’s view of Mornington Crescent Underground station. But there are striking correspondences to be found, too, in less obvious quarters. Is there, for example, a more emblematic example in twentieth-century British art of that quintessential Camden Town subject, the figure in an interior, than Richard Hamilton’s dynamic little collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? 1956, or any more uncompromising manifestation of that other familiar element in the Camden Town lexicon, the unmade bed, than Tracey Emin’s infamous arrangement of soiled sheets, cigarette butts and dirty knickers? Hamilton’s Swingeing London series, based on press photographs of Mick Jagger and the art dealer Robert Fraser, handcuffed together, being driven to court to face charges of possessing marijuana, derives ultimately from Sickert – albeit the Sickert of the 1920s and 1930s, who transformed a snapshot of King George VI and his racing manager into an unforgettable icon of modern celebrity. The series of double portraits of his artist friends in claustrophobic rooms that Howard Hodgkin made in the 1960s are imbued with the same intimations of human drama and psychological tension that animate Sickert’s conversation pieces; some of Hodgkin’s later paintings of naked couples glimpsed through shuttered windows carry an equally powerful erotic charge. Patrick Caulfield’s baleful evocations of desolate and anonymous pubs, restaurants and hotel foyers, and his uncanny ability to re-create the precise texture of their tawdry furnishings – anaglypta or lincrusta wallpapers, a Formica table-top, a cheap plastic veneer – place him in a direct line of descent from Gilman and Ratcliffe. Since the early 1970s Gilbert & George have recorded the gritty reality of their own down-at-heel corner of London with the scrupulous detachment that characterises the best Camden Town painting. Meanwhile, the Young British Artists of the ‘Freeze’ generation not only emulated the co-operative commercial enterprise that Sickert initiated in Fitzroy Street, but, as Richard Shone has pointed out with specific reference to Gillian Wearing, they also entered into a pungent re-engagement with the tradition of English realism, “rooted in oppositions of reserve and revelation”. Emin, Rachel Whiteread, Sarah Lucas and Wearing could be said to draw from the banal imagery of Camden Town: the domestic interior, beds, mattresses and the detritus of everyday life. Wearing’s 1996 video piece Sacha and Mum, in which two models act out a “skirmish of anger and tenderness”, is a sophisticated reworking of one of Sickert’s similarly contrived tableaux, “shot through with a melancholy that is an essential ingredient of all true realism”.

In January 1914 Charles Ginner published a personal manifesto in the New Age outlining the credo of Neo-Realism: “Realism, loving life, loving its Age, interprets its Epoch by extracting from it the very essence of all it contains of great or weak, of beautiful or of sordid, according to the individual temperament.” As a definition of the impulses underpinning much of the most compelling British art of the past 100 years it cannot be improved.