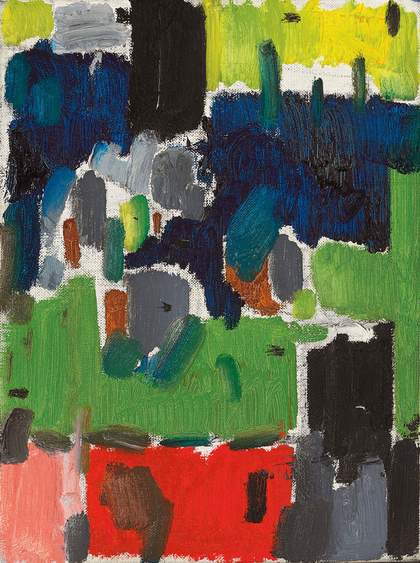

Patrick Heron

Garden Leaves 1955

Oil on canvas, 406 x 305mm

© Estate of Patrick Heron, courtesy Bridgeman Art Library, private collection

Since the 1960s at least, we have grown accustomed to seeing post-Second World War art through the lens of the New York/Paris rivalry. At most, some of us acknowledge the existence of peripheries: local champions who we may cherish, but we don’t think compete in the same league as the New Yorkers or Parisians, be they from San Francisco, Berlin, Barcelona, or St Ives. It is only very recently that there have been efforts to consider a broader, more truly international picture, united by stylistic trends or a common chronology. Such a globalised vision logically leads to the idea that the dominant trend of post-war art was what I would call an international Abstract Expressionism with local variants - a largely anachronistic notion, but all the more operative in hindsight.

At the time of Abstract Expressionism, such a global view was indeed anathema to both French and American critics and artists. For those in France who felt the coming blast of defeat, the reaction was at best to try to construct a rearguard alliance. French critic and curator Michel Tapié, who was organising exhibitions on both sides of the Atlantic, including in 1952 the first Jackson Pollock show in Paris, devised in 1954 the notion of a Pacific School to bypass New York by teaming up West Coast artists with the School of Paris, as well as Japanese painters.

Nicolas de Staël

Coin d’Atelier Fond Bleu 1955

Oil on canvas, 1950 x 1140mm

© Estate of Nicolas de Staël, private collection

For American critics, the consequences of the feud were too important even to acknowledge the existence of a US interest in Parisian artists: as early as 1947, Clement Greenberg consciously skipped the New York exhibitions of French painters when making his monthly rounds for Partisan Review. Only in England was it customary to entertain the view that there was such a thing as an international movement. This prospect was shared by critics and artists, before the advent of Pop Art made it possible to forge a strictly binational alliance, this time between New York and London.

In 1949 art critic Denys Sutton had identified the ‘challenge of American art’, but added that “European and American painting must be studied together’, citing in the same pages the ‘rich impasto’ of Nicholas [sic] de Staël and the ‘dramatic design of Hans Hartung’s pungent shapes, rhythms and exploration of the unconscious’. He heralded a type of international curiosity that helps to explain why the English reception of Tapié’s influential exhibitionOpposing Forces, when it was shown at the London ICA in 1953, was quite different from that in Paris. There, the presence of American painters such as Pollock was quickly dismissed as a mere variation on similar French experiments (for example, Jean Dubuffet’s). Whereas in London, even if the show was considered somewhat confusing and Pollock’s paintings generally ridiculed, there was a tendency to consider all contemporary abstract artists in the same breath, united by a common gestural style and process - as can be seen in Patrick Heron’s review, which singled out (with suspicion) both Pollock and Georges Mathieu, as well as Jean-Paul Riopelle.

However, views shifted as opportunities to see the new American paintings grew. The Modern Art in the United States exhibition, organised by MoMA and shown at Tate in 1956, prompted some younger critics, such as Lawrence Alloway and David Sylvester, to espouse American Abstract Expressionism as the most vital trend of their day, and British abstract painters quickly followed suit. In 1956 Alloway could report to an American correspondent: ‘I have just come back from a visit to St Ives and there, too, American styles are clear to see in the young artists.’ In March 1956 Heron wrote of the American artists seen at Tate: ‘Their creative emptiness represented a radical discovery, I felt, as did their flatness, or rather their spatial shallowness.’ And he concluded his review: ‘We shall now watch New York as eagerly as Paris for new developments.’ This shift of balance was clear when he wrote, in May of the same year, about the de Staël retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery. While he could no longer ‘shout unreserved acclaim’, he still admired ‘the non-figurative works made between 1946 and 1950 and abstract-figurative pictures of 1950-2’.

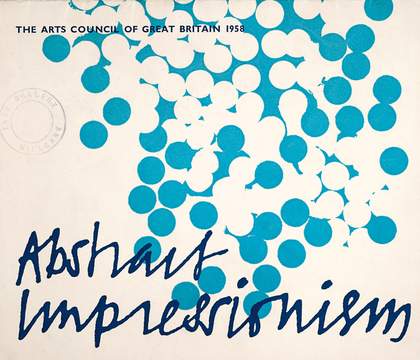

Cover of catalogue for the Arts Council's 'Abstract Impressionisms' exhibition, 1958, designed by Richard Smith

Courtesy Tate Archive

Indeed, Heron’s own work of 1955–1956 showed the deep impact of both Rothko and de Staël, with paintings made of a juxtaposition of vivid translucent patches of colours. Garden Leaves 1955 or Azalea Garden 1956 recalled at the same time Rothko’s No. 1 1948-9 - shown at Tate - and de Staël’s Coin d’atelier fond bleu 1955 - included at the Whitechapel - one of the late works where the French painter had abandoned thickness in favour of fluidity, when he was trying to tread that fine line between ‘the absolute form and the absolute unformed’. Heron’s more geometrical paintings from 1957-9, made of a succession of irregular stripes with a tonal progression, would register the influence of the so-called ‘classical’ Rothkos from the 1950s, without forgetting the ‘horizontal colours-layers’ he had admired in de Staël’s sea and sky paintings of 1952-3.

This international approach towards current abstract painting extended to the next generation of British painters, even when they were explicitly fighting against the spirit of St Ives. The young William Green, who was at the Royal College of Art from 1957 to 1959, thus conflated the impact of American action painting, popularised through the photographs and films of Pollock at work, with the spectacularisation of painting used by Mathieu when creating hisThe Battle of Hastings for his 1956 exhibition at the ICA. His bitumen paintings of 1957-8 were made by throwing tar on large panels laid flat on the floor, on which he sometimes rode a bicycle. The title of a 1957 painting, Napoleon’s Chest at Moscow (now destroyed), even showed a will to rival the French artist’s somewhat ironical relationship with history, while another work from the same year was titled Patricia Owens, the name of a Canadian actress who had just left British cinema for Hollywood.

Artist William Green using his bicycle tyres to spread liquid paraffin and black bitumen into the surface of the canvas, filmed in his London studio for Pathé News 1957

In autumn 1956 in ARK, the magazine of the RCA, the art critic Robert Melville published an essay that considered ‘action painting’ - as practised by Green and his contemporaries at the RCA, Richard Smith and Robyn Denny - a trend observable in New York, Paris and London. In a 1957 essay, Alloway would agree that this was the best way to describe an international tendency of which these young British painters were the most promising heirs. He cited among its practitioners not only American artists but also French painters such as Pierre Soulages, whom he quoted:

I work, guided by an inner impulse, a longing for certain forms, colours, materials, and it is not until they are on the canvas that they tell me what I want.

But at the end of the 1950s, the main area for considering abstract painting as a united field of experience that involved artists from northern America and Europe remained that of a renewed rapport with nature, or, more precisely, the landscape. Since the end of the 1940s, Peter Lanyon had adopted the dark structuring of flowing impressions that could be seen in the abstract landscapes of de Staël or Jean Bazaine, whose liking for those places where the sea mixes with the earth he shared, replacing the inspiration of Normandy or the Côte d’Azur with that of Cornwall. From 1956 he began to include some gestural passages, intimating a dialogue with the abstract landscapes ofWillem de Kooning, such as Easter Monday 1955-6. The way he suggested an elevated viewpoint in most of his work from the end of the decade resonated with similar devices used by Sam Francis, a Californian who had been living in Paris since 1950: his Lost Mine 1959 conflated upward and downward directions, as Francis had been doing since his early Californian paintings.

Peter Lanyon

Lost Mine (1959)

Tate

This trend among British painters (one could also cite St Ives artists such as Roger Hilton or William Scott, as well as those from the next generation, including Gillian Ayres) was echoed in the conscious efforts of critics who tried to establish gestural landscape abstractions as an international movement. Prominent among them was Alloway who, with help from the young painter Harold Cohen, organised in 1958 the exhibition Abstract Impressionism, first in Nottingham then in London. Using a phrase coined by second generation American Abstract Expressionist painters, they assembled works by American artists living in the US (among them Philip Guston) or France (Francis, Joan Mitchell, Norman Bluhm), French painters (de Staël, Pierre Tal-Coat) and British artists (Heron, Lanyon, Richard Smith), with the addition of a Canadian living in Paris (Riopelle). According to Alloway, the main feature of these diverse artists was that their paintings, which constituted ‘a development of some of the potentialities present in Action Painting’, contained ‘allusions to nature’ that ‘however… are not allowed to disrupt the autonomy of the paint.’

Sam Francis

Painting (1957)

Tate

In fact the show didn’t succeed in fostering a general consensus that such an international movement existed. Alloway himself had already expressed some reservations when writing an essay on ‘English and International Art’, published in the winter of 1957-8. A simple quote is enough to indicate that, even for him, national trenches were back with a vengeance: ‘Heron… turns Sam Francis into weather reports.’ St Ives painters continued to practice what they saw as linked to both French and American art, while Rothko visited Paris and St Ives during the summer of 1959 (as did Greenberg) and confirmed his friendship with Soulages and Lanyon, but generally the French and American art worlds chose to concentrate on reviving their feud - and simply dismiss each other. Also, 1959 signalled the advent of new trends that had nothing to do with either gesture or nature: Pop Art and Minimalism. It is only half a century later that we can again dispense with nationalistic chauvinism and realise that some of the intuitions embodied in the paintings and words of British painters and critics made sense.