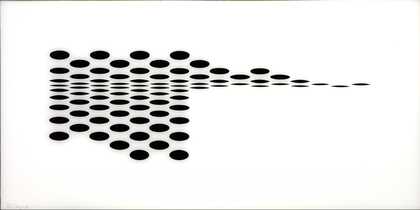

Lubaina Himid on Bridget Riley’s Fragment 7/5 1965

Bridget Riley

Untitled [Fragment 7/5] (1965)

Tate

I love Fragment 7/5. It sucks my whole body, fingers first, into its dangerous centre.

watery slippery dropping falling popping linking sliding sinking

rounded circled ringed flushed flattened squeezed trapped crushed

squinting peering staring blinking searching straining raining down springing up

hocus pocus focus magic disappearing trick sliding forward pushing backwards climbing in

Since encountering Bridget Riley’s work at Tate in the late 1960s, I have tried to understand it – as a way of helping me to construct something which seduces a viewer into a conversation, then challenges, questions and encourages action. I try to use paint to convey the danger and despair central ot my practice.

Between 1998 and 1999 I spent two months as artist-in-residence at Tate St Ives. Riley grew up in Cornwall, and while there I read many of her texts. It wasn’t until then, painting the sea, the sky and the beach from the lifeguard’s hut in front of the gallery, that I truly understood what she meant by ‘a constant interchange of horizon lines, cliff-tops and brows of hills – narrow slivers of colour rhythmically weaving and layering, edge against edge’.

My strongest motivation for being an artist is to make visible the cultural contribution of people from the black diaspora. But Riley’s influence is often present in my paintings, and the reasons are intricate yet simple: her ability to attract and repel, to lure and to dazzle, to burn a painted image, visible yet invisible at one and the same time.

Peter C van Wyck on Claude Cahun’s I Extend My Arms 1931 or 1932

I have been writing about survivor trees and tsunami stones, atomic photographs, keraunography and the predicament of theorists who lose their ground. But then – quite unexpectedly – this image floats up in a search for landscape photography. Saxa loquuntur, it seems ot proclaim (thinking here of a pithy line by Freud, the great Viennese archaeologist of the unconscious). The stones speak! Claude Cahun’s photograph – here unmoored from its surrealist roots and commitments – speaks. True, in 1931 this image may have seemed a whimsical, earthly fable – or trick of the light – but today it takes on more urgent qualities of a peculiar kind of mapping; a critical topography we might call it.

What we see, while figurative in its way, is properly an anthropolith, a human in lively entanglement with the earth. As I think about this figure it seems richly laden with the allegorical freight of Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus 1920 by way of dear old Walter Benjamin’s tired ‘Angel of History’. Only this time the disorientated angel, encased in stone, cannot see the catastrophe, nor the wreckage piled at her feet; she cannot see at all. Blind to the very predicament in which she finds herself.

If this thought has a certain resonance, well it should. It stands as a lovely visual and topographic study of what we might call the condition du jour, the anxious diagnosis of which has come to be called the Anthropocene. This term describes our current geological era, but also highlights the growing recognition of the inseperability of human and natural history, out of which has emerged an awareness of a new geological condition of planetary crisis. It also suggests the most recent moral and aesthetic narrative of our self-diagnosis – I’m pretty sure that no one has ever called the previous epoch, the Holocene, a ‘condition’.