Editor’s note

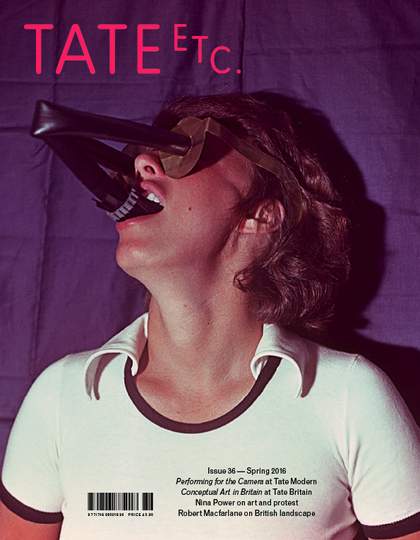

Alexander Melamid and Vitaly Komar first met in a morgue in 1963, drawing anatomy sketches as art students in Moscow. The pair would later go on to collaborate for more than 25 years on countless satirical portraits and installations, forming their own ironic take on pop and conceptual art. Their Superobjects: Supercomfort for Superpeople 1975 project, one part of which features on this issue’s cover, was a mock catalogue for products that might simply look like junk, but were promised to have nearmiraculous, life-improving qualities. When they applied to leave the USSR in 1977, though, only Melamid had as yet been given a permit to emigrate. When asked how the two-man collective might continue to work together, Komar responded drily: ‘We’re going to try telepathy.’

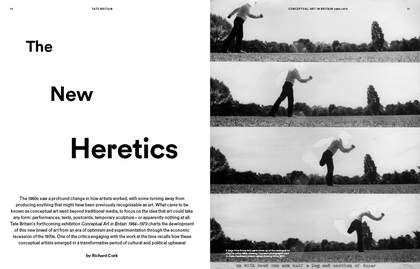

This issue of Tate Etc. intended to focus, more than usual, on the lesser-remarked works in the Tate collection, to shine some light on corners left normally unexplored. But what began to happen was almost telepathic, as connections and links between different sections of the magazine began to appear unbidden. Writers and contributors were looking at the same artists or artworks for very different reasons, and other direct links began to thread their way through our pages, such as those between Victor Pasmore, a member of the brief Objective Abstraction movement, and one of the teachers of Roy Ascott, who in turn later taught Stephen Willats, one of the artists in Tate Britain’s upcoming exhibition Conceptual Art in Britain 1964 - 1979.

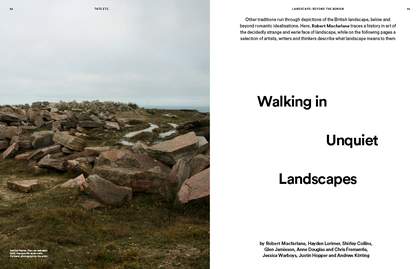

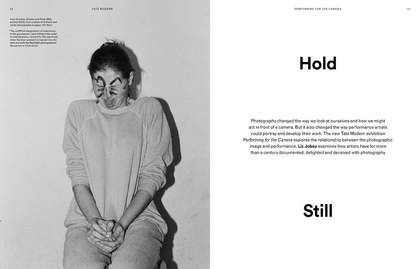

But more subtle connections also became apparent. Our extended feature ‘Walking in Unquiet Landscapes’ offers a contemporary reassessment of landscape from a range of writers, poets, musicians and artists, but it also shows how the written word and photography have helped in shaping our experience of landscape. The artists discussed here from both the Performing for the Camera and conceptual art exhibitions provide countless examples exploring this further. Meanwhile, in her essay ‘The Art of Protest’, Nina Power examines how artists globally have worked within and in response to crisis and conflict, but it also highlights how many of the new artistic voices and approaches described in several of our features have arisen from moments of upheaval. What the diverse connections here make clear is that art is integral in simultaneously understanding and creating the world around us.

What has emerged in this issue is a potted, alternative history of the 20th century, tracing the groundwater and hidden currents, where influences and ideas work their way unexpectedly and indirectly. What we can find here are artists involved in both radical social changes and the quieter, slower shifts in our surroundings, creating new forms of communication and synthesis. We may not be telepathic, but what they might be trying to tell us is that the world can be reshaped and inverted with the simplest of gestures.

Chris Fite-Wassilak, guest editor