Alberto Giacometti Walking Man I 1960 Collection Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris (inv. 1994-0186) © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS+DACS, 2017

Alberto Giacometti was one of the great painter-sculptors of the twentieth century. A restless innovator, he experimented with a range of styles, art historical sources and materials, whilst retaining a unique, immediately recognisable artistic vision. This exhibition is the first large-scale retrospective of his work in the UK for twenty years. Through unparalleled access to the collection and archive of the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris, it traces Giacometti’s career and demonstrates his fascination with different materials and textures, such as plaster, clay and paint. As well as bronze figures and portrait paintings, the exhibition includes plaster sculptures, decorative objects, and drawings that have never been seen before.

Born in 1901, Giacometti grew up in an alpine village in Bregaglia, Switzerland. He was the eldest child of Giovanni Giacometti, a post-impressionist painter, and Annetta Giacometti-Stampa. As a teenager, surrounded by his father’s paintings, books and art journals, Giacometti began to make drawings, oil paintings and sculptures.

In 1922 he came to Paris, where he engaged with movements such as cubism and surrealism. Interested in the experience and the mechanics of looking, he eventually returned to working directly from live models, and created sculptures in a stylised but more realistic manner. For most of the Second World War he was in Geneva. When he returned to Paris after the war, he went on to create the elongated figures with highly textured surfaces and the distinctive portrait paintings for which he is best known.

Alberto Giacometti Head of Isabel 1936 Collection Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris

(inv. 1994-0343) © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS+DACS, 2017

Room one

When you look at the human face, you always look at the eyes. An eye has something special about it, it’s made of different matter than the rest of the face.

Giacometti returned to the depiction of the human head throughout his career. His subjects were the people to whom he felt closest, including his mother and father, his brother Diego, his wife Annette, and friends such as the philosopher Simone de Beauvoir. They sat for him for hours on end, but he would also work from memory. This opening room shows a selection of heads in different materials and styles, ranging from early naturalistic sculptures that Giacometti created as a teenager, such as Head of a Child [Simon Bérard] 1917–18, to works from the 1950s and 60s with their distinctive highly textured surfaces. Although many of his sculptures were eventually cast in bronze, Giacometti preferred to work with clay or in plaster, materials which he could form and shape with his own hands.

Alberto Giacometti Hour of the Traces 1932 © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS+DACS, 2017

Room two

I have made sculptures that can move! […] These are more joyful works and I had a lot of fun making them. […] I have absolutely no idea how the next one will come out, and it’s a very pleasant feeling.

In the mid-1920s, Giacometti became frustrated by the difficulties of capturing the appearance of a living model. He began to explore more conceptual approaches, responding to the formal innovations of sculptors like Henri Laurens and Constantin Brancusi, and the abstraction of African and Oceanic objects. Giacometti’s sculptures from this period show a transition from naturalistic to more abstract forms. He continued to investigate the head and the human gaze, but progressively withdrew from resemblance. His Gazing Head 1929 sculpture is a rectangular ‘plaque’, shown here in the plaster and terracotta versions.

Giacometti’s highly original work drew the attention of the surrealists, led by André Breton, and from 1932 he began to participate in the activities of the group. He was sympathetic to their rejection of tradition, morality and the bourgeoisie, and his work of this period shows his fascination with the unconscious. Sculptures such as Caught Hand 1932 and Hour of the Traces 1932 include powerful and disturbing symbolic objects, suggestive of violence and death. In 1932 Giacometti’s first solo exhibition was held at the Pierre Colle gallery. Its first visitors included Pablo Picasso.

Room three

Objects interest me hardly any less than sculpture, and there is a point at which the two touch.

In order to earn a living during the 1930s, Giacometti produced decorative objects such as lamps, vases, jewellery, and wall reliefs. He collaborated with interior designer Jean-Michel Frank, and was helped by his brother Diego, who had moved to Paris and settled into a dual role as Giacometti’s studio assistant and his most important model. These decorative works were highly acclaimed and featured in magazines such as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar.

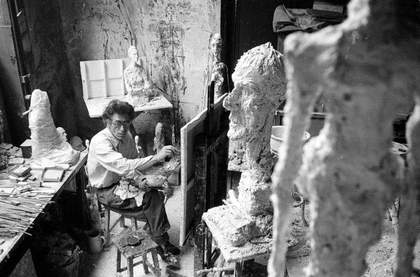

In the cabinet in this room, Giacometti’s Disagreeable Object 1931 sculptures are displayed alongside decorative pieces and notebook sketches. Giacometti did not think of his design works as insignificant, and on several occasions they influenced his practice as a sculptor, and vice versa. Drawings such as Lunar 1933 exemplify how Giacometti often made sketches of his sculptures. His small studio, increasingly crammed with sculptures, was an important environment for the artist throughout his career.

This room also explores Giacometti’s involvement with surrealism. He published in surrealist journals, exhibited with other surrealist artists at the Salon des Surindépendants in 1933 and socialised with them in cafés, bars and brothels such as Le Sphinx in Montparnasse, which was a favourite artists’ haunt.

Alberto Giacometti Spoon Woman 1927 Collection Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris (inv.1994-0297) © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS+DACS, 2017

Room four

During those years I executed only sculptures that were complete in my mind’s eye. I limited myself to constructing them in space without stopping to ask myself what they might mean.

This room includes Giacometti’s most substantial works from the 1920s and 30s. Spoon Woman 1927 takes its shape from a ceremonial spoon identifiably from the Dan culture in West Africa, whilst also reflecting influences of cubism. Transposing a ritual object into sculpture, it is arguably Giacometti’s first standing woman.

The frozen pose of Walking Woman [I] 1932 reflects Giacometti’s fascination with Egyptian art. The sinuous curves, the visible bosom and recognisable slit of the genitals evoke a sensual image of femininity. Woman with her Throat Cut, from the same year, is one of Giacometti’s most violent surrealist sculptures. The abstracted hybrid of plant and insect appears to be in the throes of death, while her tense, pointed forms also suggest a trap threatening to shut tight.

In 1933, Giacometti’s father died. Giacometti responded with the sculpture of a monumental cult-like figure, Invisible Object 1934–35. Its sources ranging from ancient Egyptian objects to Christian sculpture have been much discussed by art historians; the title ‘invisible’ is thought to refer to the deceased. Giacometti’s most abstract sculpture Cube 1933–34 also seems to relate to his father’s death, its closed geometric form inspired by Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer’s engraving Melencolia I. Giacometti organised exhibitions of his father’s work in Switzerland and created a tombstone for his grave in 1934. After his return to Paris, he continued his studies of heads.

For the surrealists around André Breton, these ‘realistic’ works after models were considered to be treason and Giacometti left the group. However, he agreed to include his sculptures in exhibitions such as the International Surrealist Exhibition in London in 1936. The British press was highly critical, with headlines such as ‘Surrealist Art is Clumsy as well as Meaningless’. However, the exhibition was well-attended by the public and members of the art world alike.

Alberto Giacometti Very Small Figurine c.1937-1939 Collection Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris (inv. 1994-0442) © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS+DACS, 2017

Room five

By doing something a half centimetre high, you are more likely to get a sense of the universe than if you try to do the whole sky.

In May and June 1940, the German army swept into France. Paris was occupied. When Giacometti went to see his mother in Geneva, he was denied a re-entry visa to France, and spent the rest of the war in Switzerland, while Diego looked after the studio in Paris. Living and working in a hotel room in Geneva, Giacometti regularly met with friends, including publisher Albert Skira, photographer Eli Lotar, and the painter Balthus. In 1943 he met Annette Arm, a young woman who worked in an office at the Red Cross. A few years later, she became his wife and most important female model.

Throughout the war, Giacometti made sculptures, including standing figures and portrait busts. Many of these were very small, as if capturing a human presence from far away. ‘I wanted to make a sculpture of this woman as I had once seen her some distance away on the street’, he later recalled, relating these works to the experience of watching his friend, the English artist Isabel Nicholas (later Lambert and Rawsthorne) on the Boulevard Saint-Michel.

Room six

I wanted to hold on to a certain height, and they became narrow [...] The more I wanted to make them broader, the narrower they got.

In 1945, Giacometti returned to Paris and his studio on rue Hippolyte-Maindron, where he began to produce the elongated figures that characterise his post-war sculpture. When they were exhibited at Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York in 1948, the catalogue included an essay by the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, entitled The Search for the Absolute. Together with atmospheric photographs of Giacometti’s studio, the essay set the tone for the reception of Giacometti’s work. The attenuated forms and isolated figures were interpreted as embodying human anxieties and alienation. Through extreme reduction, Giacometti succeeded in sculpting a powerful image of humanity in which a generation traumatised by the war could recognise itself.

An exhibition of these works in 1951 at the Galerie Maeght in Paris helped to establish his fame in Europe. In 1955, two extensive exhibitions were presented simultaneously, by the Arts Council Gallery in London and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Installation view of the Women of Venice 1956 in Alberto Giacometti at Tate Modern

Collection Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris

© Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS/DACS, 2017

Courtesy of Tate Photography

Room seven

Egyptian statues have grandeur, harmony in their lines and forms, perfect technique […] And how animated their heads, as though they really were looking or talking.

As a child, Giacometti regularly copied images from reproductions in his father’s books and magazines. He never lost the habit, and continued to find great pleasure in sketching copies into his notebooks, magazines, or books. He had an enduring fascination with Egyptian sculpture and used it as a source for his own art, as the works in this room demonstrate.

In 1956, Giacometti represented France at the Venice Biennale. He created an extended series of sculptures: Women of Venice 1956. The majestic, elongated nudes with their pronounced base-like feet, over a metre in height, were exhibited alongside works from earlier in his career. As well as recalling Giacometti’s interest in Egyptian statuary, they reflect his lifelong search for an adequate representation of the female form. Eight of the surviving nine Woman of Venice plaster works are shown here. The original plaster works, five of which were restored by the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris especially for this exhibition, are reunited for the first time in sixty years.

Alberto Giacometti Man Pointing 1947 © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS+DACS 2017

Room eight

I have the feeling, or the hope, that I am making progress each day. That is what makes me work, compelled to understand the core of life.

Painting dominated Giacometti’s early years, but when he moved to Paris in 1922 he focused on sculpture. After the Second World War, painting became an important part of his practise again. This room includes portraits of the artist’s mother, of the writer Jean Genet, and of the Japanese philosopher Isaku Yanaihara. During his childhood Giacometti often sat as a model for his father. Working at close quarters from a living model subsequently provided him with his greatest challenge. He worked from the model as well as from memory, obsessively seeking to depict a human presence.

Figures such as Walking Man 1947, Man Pointing 1947, and Tall Woman 1958 demonstrate Giacometti’s concern with capturing movement as well as stillness. The Nose 1947 and The Hand 1947 combine the thin human form with a mystical and violent language reminiscent of Giacometti’s surrealist phase. The Nose and Head on a Rod 1947 can be seen in relation to Giacometti’s interest in death and the transformation of the living body into a motionless corpse. Giacometti often recollected how he had witnessed the death of a travelling companion at a young age, which had a traumatising effect on his vision:

In a few hours Van M. had turned into an object. A nothing. That meant, of course, that death could come at any moment, to me, to the others.

Alberto Giacometti Bust of Annette VII 1962 Collection Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris (inv. 1994-0246) © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS+DACS, 2017

Alberto Giacometti Bust of Diego c. 1956 Collection Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris (inv. 1994-0275) © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS+DACS, 2017

Room nine

Diego has posed ten thousand times for me. When he poses I don’t recognize him. […] When my wife poses for me, after three days she doesn’t look like herself. I simply don’t recognize her.

Personal relationships were always important to Giacometti, and his models were usually friends or family. This room is dedicated to portraits of Giacometti’s most significant models: his brother Diego and his wife Annette.

Giacometti controlled the studio set up and confronted his sitters from a distance of around three metres away in long, intense portraiture sessions. He scrutinised and re-examined the facial features, framing them in a flurry of lines and brush marks, continuously painting, overpainting and repainting, modelling and remodelling his work. Giacometti was rarely satisfied with the end result, claiming that the works lack in ‘likeness’. The sculptures and paintings of Diego and Annette demonstrate Giacometti’s intense observation of the human face and figure, focussing on the eyes of his sitter and tracing their movements whilst seeking to translate his perception of the human into the reality of a new art image.

Alberto Giacometti Four Figurines on a Base 1950-1965, cast c.1965-6 Tate © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS+DACS, 2017

Room ten

I don’t mind whether the exhibition presents success or failures. … I have no requests, merely to proceed feverishly.

In the last ten years of his life, Giacometti was a famous and well-paid artist. However, his lifestyle remained unchanged. He wore simple, often plaster-spattered clothes and worked late into the night. After waking up around noon, he had lunch at a café nearby, and at night frequented the bars and nightclubs of Saint-Germain-des-Prés and Montparnasse.

One of the most important subjects of Giacometti’s late paintings is a young woman known as Caroline, who attracted his attention when their paths crossed at a nightclub. Between 1960 and 1965 Giacometti painted numerous portraits of his mistress.

In 1965, the Tate Gallery organised a comprehensive retrospective of Giacometti’s work, curated by the critic David Sylvester. During the installation, Giacometti set up a studio in the basement of the gallery, where he continued to work on sculptures for the exhibition. Among these was the plaster Four Figurines on a Stand, a bronze version of which was acquired by Tate along with other sculptures and two paintings. Giacometti wrote to the director, Norman Reid:

May I tell you again how much I enjoyed my visits to London and how touched and grateful I am that you have chosen so many works for the Tate Gallery [...] I hope to come to London next spring.

Before he could make the trip Giacometti died at the age of sixty-six on 11 January 1966, after years of chronic bronchitis. His art continues to be exhibited worldwide, and has influenced and inspired artists of subsequent generations.

Giacometti is on at Tate Modern 10 May – 10 September 2017