Curators jumped at the chance of calling this colloquium ‘inherent vice’ because, what was a familiar term for conservation practice was a new one to them. In fact, the definition of inherent vice – while it reflects very accurately the problems posed by Naum Gabo’s plastic sculptures (which provoked this research project at its outset) by no means cover the range of questions raised by the question of replication. Nevertheless, I might define inherent vice more widely, given that replication is integral to the practice of sculpture.

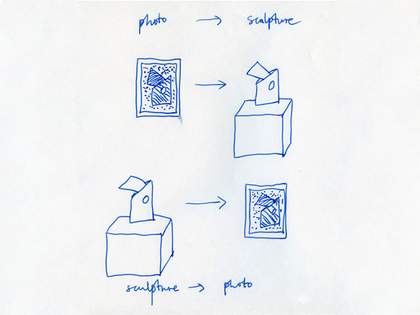

It should not surprise us that the topic raises rich and complex questions in a way that it cannot for painting. Sculpture has always embraced seriality and repetition, and some would argue that traditional bronze casting is as much part of today’s subject as any apparently more vexed issue of reproduction. In terms of those who have come to this forum, however, and the case studies which they represent, we are not dealing with the questions of life-time or posthumous casting, but rather with replication in other materials, and often in media with a short material history, and with a somewhat imagined relationship to the ‘original’, which may never have been materially defined. The fact that we are dealing with modern sculpture, and thus with an era of photography, returns us again and again to paper documents which give us incomplete material evidence. That is to say, a photograph can lead to a replica, or an object can lead to a photograph. In some cases, it will be argued, a photograph may be the most suitable way to document a sculpture, especially when that sculpture may be essentially performance based.

I have been assigned six papers which might be seen to provide us with six key case studies, and thus to set up a point of departure for the conference as a whole. I think it might be most helpful if I try and represent the points which they cover, so as to reflect the range of positions with which we are immediately confronted, and so as to lay some basic markers, although each of these papers has a wealth of minutiae connected with its own particular story. This colloquium was intended to bring curators and conservators together, and these topics, and these particular papers show how crucially the question of conservation affects the scope and meaning of art history.

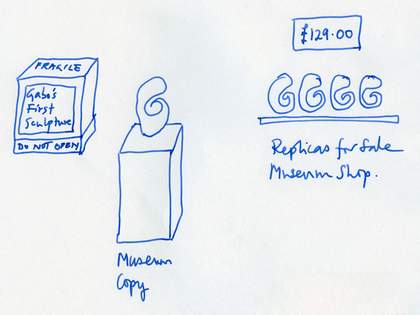

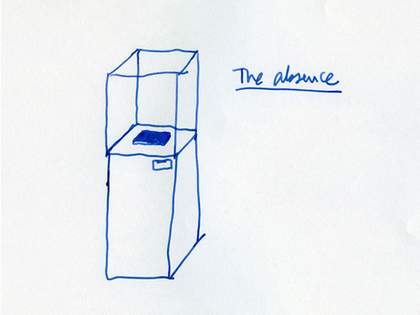

Fig.1A

Penelope Curtis

Illustration No.1a

© Penelope Curtis/The Henry Moore Foundation

Fig.1b

Penelope Curtis

Illustration No.1b

© Penelope Curtis/The Henry Moore Foundation

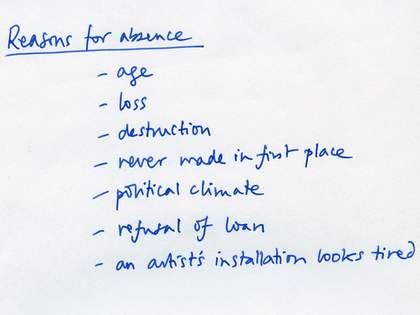

Reasons for absence

Although the Gabo situation, with which this project began, sets up a particular set of parameters, the reasons for an artwork’s absence are varied.

- Sculptures age, whether they are made from a known or an unknown material.

- Sculptures get lost.

- They get destroyed (as often as not by the artist).

- They were never made in the first place.

- A particular political climate makes it impossible or possible for them to be made (the pre- or post-Perestroika USSR).

- A much wanted loan is refused.

- An artist’s installation starts to look tired

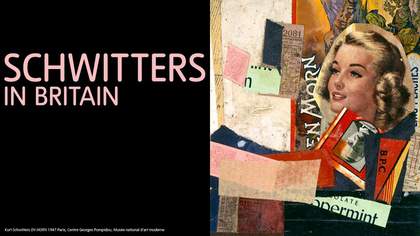

Fig.2a

Penelope Curtis

Illustration No.2a

© Penelope Curtis/The Henry Moore Foundation

Fig.2b

Penelope Curtis

Illustration No.2b

© Penelope Curtis/The Henry Moore Foundation

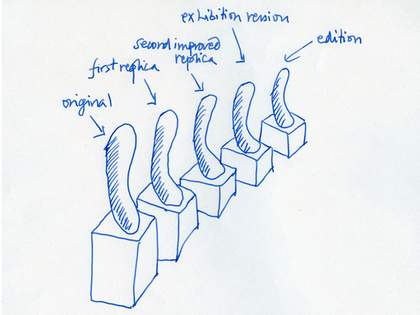

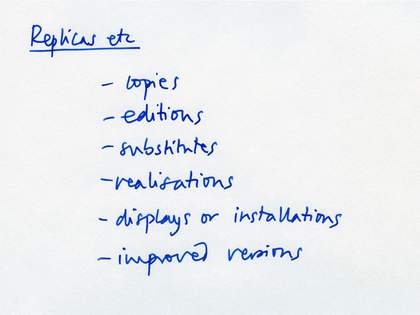

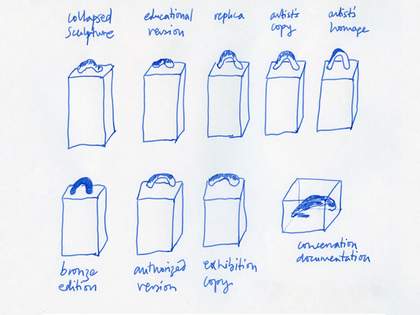

Replicas

It is abundantly clear that we are dealing with various kinds of replicas, some of which are slow and some fast, some spontaneous and some re-considered:

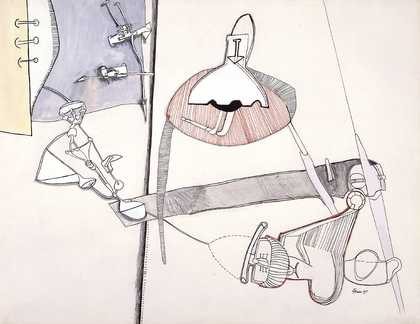

Fig.3a

Penelope Curtis

Illustration No.3a

© Penelope Curtis/The Henry Moore Foundation

Fig.3b

Penelope Curtis

Illustration No.3b

© Penelope Curtis/The Henry Moore Foundation

- Copies.

- Editions (for example, Rodchenko in one plus twelve replicas).

- Substitutes.

- Realisations.

- Displays or installations (which range from Joseph Beuys’s Darmstadt Block to something which might be more accurately described as a performance, for example, with Dieter Roth).

- Improved versions (for example, Tatlin’s Monument as produced by successive interpreters, in Stockholm, London and Paris from 1968 to 1979, including the Longepe Joinery, which joined MNAM, and Rodchenko.

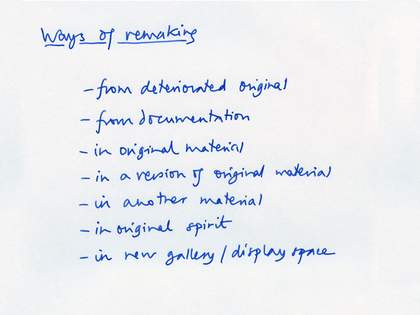

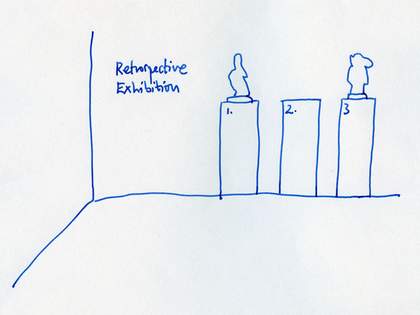

Ways of remaking

One might divide this section into two: retrospective making, and prospective making, in terms of whether works are re-made from documentation or made up for the first time from plans. These papers present us with different ways of remaking:

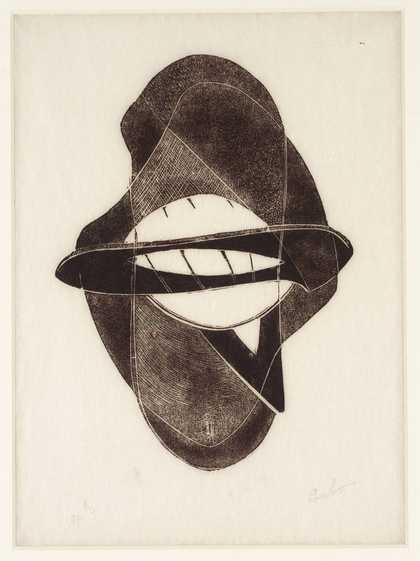

Fig.4a

Penelope Curtis

Illustration No.4a

© Penelope Curtis/The Henry Moore Foundation

Fig.4b

Penelope Curtis

Illustration No.4a

© Penelope Curtis/The Henry Moore Foundation

- From a deteriorated original.

- From documentation (usually photographic) (for example, Kurt Schwitters)

- In the original material (for example, in Eva Hesse’s Cementex latex rubber is unchanged).

- In a version of the original material (for example, Hélio Oiticica’s materials may no longer exist in quite the same form).

- In a quite different material (for example, with Alexander Rodchenko, where first plywood replaces cardboard, and then aluminium replaces wood).

- In the original spirit (for example, Oiticica’s capes made by others in the start, or exist in several versions), perceived fulfilment of the artist’s wishes (see Rodchenko).

- The same works are re-positioned in a newly refurbished space (Beuys).

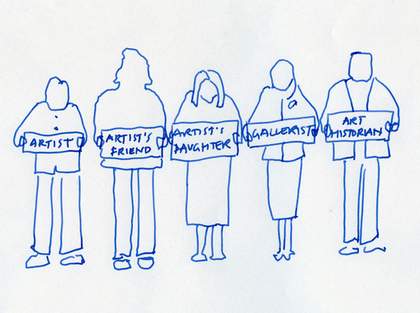

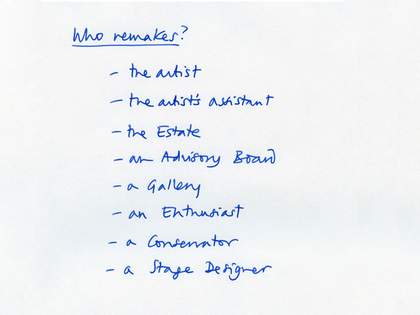

Who remakes?

These papers present us with a range of more or less obvious possibilities, which also leave us with the interesting question of copyright even shifting from the original artist to the maker of the replica (as with Schwitters’ remake):

Fig.5a

Penelope Curtis

Illustration No.5a

© Penelope Curtis/The Henry Moore Foundation

Fig.5b

Penelope Curtis

Illustration No.5b

© Penelope Curtis/The Henry Moore Foundation

- The artist, if alive, often returns to his or her own works (for example, Rodchenko made them for the museum collection).

- The artist’s assistant (for example, Hesse’s assistant, Doug Johns), with more or less fidelity.

- The Estate.

- An Advisory Board (for example, Oiticica), often including the artist’s friends.

- A Gallery.

- Enthusiasts (for example, John Milner in the case of Rodchenko, Martyn Chalk for Tatlin).

- A conservator (for educational (for example, process-based) or for aesthetic (for example, outcome) reasons).

- A stage designer (for example, in Schwitters’s case with Peter Bistegger).

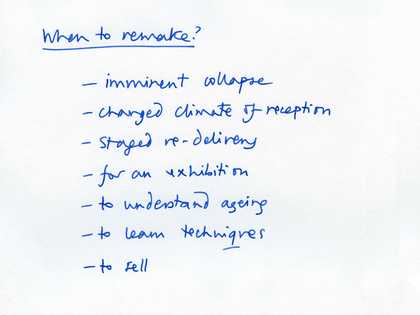

When to remake?

- Imminent collapse of a work (whether unplanned: Gabo, or planned: Roth).

- A changed climate of reception (Rodchenko).

- Staged re-delivery.

- When an exhibition is dependent on them (for example, Szeeman’s Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk commissioned Bistegger, or Rodchenko).

- When we want to understand aging and its variable effects (for example, with Hesse’s sections).

- When we want to learn techniques from an assistant (Doug Johns).

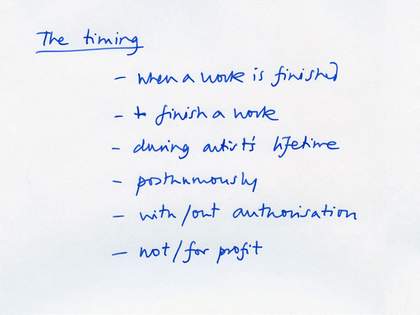

Replicas can be made:

- When a work is finished.

- Or they can finish a work (the Merzbau was never finished, but the reconstruction freezes it).

- During an artist’s lifetime.

- Or posthumously.

- With or without authorisation, which might in any case be assumed by the same person for example, the cataloguer is also the replicator (as with Lavrent’ev and Rodchenko).

Fig.6a

Penelope Curtis

Illustration No.6a

© Penelope Curtis/The Henry Moore Foundation

Fig.6b

Penelope Curtis

Illustration No.6b

© Penelope Curtis/The Henry Moore Foundation

The afterlife of the replica

Replicas can be moving (Brett on Oiticica), or more simply informative. Replicas made for exhibitions may later be bought for museum collections, and thereby shift in status (for example, Schwitters). Their afterlives are varied, ranging again from purely temporal affect (with Oiticica the aim is often still to escape permanence), to a long-term duration which effectively replaces the original or ‘prototype’ sculpture. Replicas can be duplicates, which might age more slowly than the original (Roth). Replicas can also be made of replicas, as with the travelling version of Bistegger’s Merzbau. Many of these papers lead to a similar period, so that we can speak of the periodisation of the replica, from a more open, experimental period of the exhibition reconstructions of the late 1960s and 1970s, to the market-led editioning of the post-1980s. We may be in a more vexed period now, when, although we accept earlier replicas as museum works, we doubt whether we should do the same thing again. These papers teach us that replicas are made in the light of one generation’s taste, providing a post priori reading of what an earlier work is understood to have been striving for, and the dangers of that, but also that we cannot escape the world of replicas, which are all around us, often without our even knowing.