Fig.1

John Everett Millais

Lorenzo and Isabella 1848–9

Oil paint on canvas

1030 x 1428 mm

Walker Art Gallery

© 2012 National Museums Liverpool

Fig.2

John Everett Millais

The Bridesmaid 1851

Oil paint on panel

279 x 203 mm

© The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

On 2 May 1851, during a crisis point in his career, the twenty-one-year-old Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais wrote to his friend Martha Combe: ‘One great encouragement to me is the certainty of [a picture] having this one advantage … that it is all at once put before the spectator without that trouble of realisation often lost in the effort of reading.’1 This essay looks at a pattern of sexual images ‘lost in the effort of reading’. Some, such as the phallic shadow projecting from the groin of the foreground figure in Lorenzo and Isabella 1848–9 (fig.1), appear to have been unseen, having attracted no mention in critical commentaries of the work.2 Others, such as the ‘unmistakably phallic’ horizontal leg in the same painting, are apparently visible only to post-Freudian eyes. They have been assumed to have been accidental or repressed on the part of the artist or other Victorian viewers.3 Occasionally humour or prurience is admitted, something like the ‘penis rather better’ banded about by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood as the secret meaning of their initials.4 Recent scholarship, however, has questioned these assumptions. For example, the art historian Tim Barringer writes of Millais’s The Bridesmaid 1851 (fig.2):

While the orange blossom pinned to her chest is a symbol of chastity, the woman is contemplating with fear and fascination future sexual consummation. This is hinted at by the phallic shape of the sugar caster, disrupting the work’s symmetrical composition, a symbol (though presumably not a conscious one on Millais’s part) of the man whom she is hoping to visualise.5

Fig.3

John Everett Millais

Detail of Lorenzo and Isabella 1848–9

Oil paint on canvas

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

© 2012 National Museums Liverpool

The salt cellar spilling its contents through the shadow on the white cloth in Lorenzo and Isabella, dispels doubts about whether such sexual connotations were ‘conscious’ (fig.3).6 The evil omen of spilt salt derives from the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s description of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper 1495–8 (Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan), an important source for the painting. However, bringing it together with shadow and groin animates what might be dismissed as an unconscious or covert visual innuendo with an unambiguous equivalent for ejaculation.7 Millais based his picture on John Keats’s poem Isabella or The Pot of Basil (1818); the repetition of the shape of the shadow in the switch-blade kick of the foreground figure presages the metaphorical castration and the darker spill of blood that takes place when he and his brother behead lovelorn Lorenzo later in the poem. The fallen salt cellar informs, in turn, the silver vessel placed on a white cloth in The Bridesmaid. Where the spilt salt implies bitterness and incontinence, the upright sugar caster suggests containment, swelling and sweetness. These are only hints of a serious sexual poetry in Millais’s work, which, this essay will argue, was as deliberate, rich and innovative as any in the writings of William Shakespeare, Keats or his contemporaries such as Alfred Lord Tennyson.8 A full survey is a task for a longer text; the present study will focus on the appearance of the caster and its associated imagery in a small group of works made between 1849 and 1854.

The appearance of the sugar caster should first be put into the context of its disappearance, the peculiarity that the salt and shadow, placed centrally in the picture, have gone unremarked in modern criticism. Whether it was observed by the Victorians themselves is uncertain. In 1908, the German art critic Julius Meier-Graefe singled out Lorenzo and Isabella for his tirade against English art in his book Modern Art; Being a Contribution to a New System of Aesthetics. In Meier-Graefe’s eyes it exemplified Pre-Raphaelite ‘barbarism’: Millais’s ‘pompous’ Florentines were ‘unpleasant to the point of indecency’, clowning dilettantes in fancy dress rather than true Italians and contemporaries of Donatello.9 In 1899, John Guille Millais’s reverent two-volume monograph on his father presented the picture as a brief and misguided result of the influence of the ‘perfervid imagination’ of Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti.10 When Lorenzo and Isabella was first exhibited fifty years before, the critics were, as John Guille Millais noted, divided or silent. The verdict in the Athenaeum is the most pertinent. It complained of ‘the utter want of rationality in the action of the prominent figure’, but only cited specifically the ‘unwieldy leg’.11 The public, John Guille Millais recorded, generally considered the picture a ‘prime joke’, and greeted it with ‘laughter and supercilious smiles’.12

The best reason to believe that explicit imagery was visible to some Victorian viewers of fine art comes from the continued popularity of the eighteenth-century painter and printmaker William Hogarth. Engraved editions of his pictures were widely available and consumed, and mid-nineteenth-century commentaries describing ‘a very exact representation of what were then the nocturnal amusements of a brothel’ were far from coy.13 Hogarth was a hero of the Pre-Raphaelite circle, although John Guille Millais does not mention him.14 In a letter of 1855, the poet William Allingham asked Millais to ‘be our better Hogarth’.15 In this he echoed the words of Hogarth himself; a text well known to the Brotherhood recorded the earlier painter’s hope that future ‘better hands’ would realise his search for a reconciliation of caricature and high art.16 In the case of Lorenzo and Isabella, the Athenaeum connected the two in reverse, seeing it as high art ‘almost’ reduced to ‘caricature’.

The Athenaeum reviewer, and Millais himself, may have been thinking of Hogarth’s riotous feast scene in The Rake’s Progress called The Orgy 1733, and specifically the rake’s white stockinged leg flung across the foreground (fig.4). Hogarth’s series of oils had been on show in the Sir John Soane Museum for the benefit of students since 1810. Engraved versions of The Orgy, called ‘The Tavern Scene’, reverse the painting to place the rake, like Isabella’s brother, at the left of the composition (fig.5).17 The Orgy also features a single shadow cast across the table in a nearly identical position to that in Lorenzo and Isabella. It is created by a knife, thrust by a woman over the table and echoed by the neck of a bottle, grasped by another woman under the table; the base of the bottle nestles suggestively in a parting in her pink dress.18 Its angle is answered by the rake’s foot. Phallic association of the shadow itself is strengthened in a similar way to that in Lorenzo and Isabella by objects on the table: a pair of spherical containers (a little bottle and a glass) makes an anatomical analogy to testicles.19

Fig.4

William Hogarth

The Rake’s Progress: 3. The Orgy 1733

Oil on canvas

625 x 752 mm

Sir John Soane’s Museum

William Hogarth

A Rake’s Progress (plate 3) (1735)

Tate

There were, therefore, artistic precedents for Millais’s shadow and salt cellar and these were reflected in the spirit, if not the detail, of contemporary criticism. It is unlikely that such sexually explicit imagery went entirely unseen in his time, and certainly he saw them himself, as did his Pre-Raphaelite colleagues. Why, then, has it been unseen in ours? Several decades have passed since the exposés of 1960s Pre-Raphaelite biographies gave way to the less light-hearted deconstructions of patriarchal power, inspired by the theories of feminism and those of the philosopher Michel Foucault, which followed in the 1970s.20 Indeed, the subject of sex might be thought to have been exhausted. Instead it has become strangely denatured, whisked away into other discourses. Sex in Victorian art became almost synonymous with gender; the sexual body was framed in terms of codes that constructed masculine authority over a feminine ‘other’.21 So compelling were these important and far-reaching critical revisions that it was difficult to view sex in any other way, so much so that the historians James Eli Adams and Andrew Miller, in their book Sexualities in Victorian Britain (1996), declared ‘the highly visible elusiveness of sex as a discursive production and historical topic’.22

Foucault argued in his three-volume study The History of Sexuality (1976–8) that nineteenth-century discourses of sex were displaced into discourses of power, an argument that seemed to apply to the twentieth century too. Indeed Foucault acknowledged this by asking, in the introduction to the first volume, ‘Was there really a historical rupture between the age of repression and the critical analysis of repression?’23 The text answers its question with a virtuoso exhibition of its own thesis. The only direct reference to the sex act occurs early on, an account of an encounter in 1867 between a homeless simpleton and a child: ‘At the border of a field he had obtained a few caresses from a little girl’, ‘the familiar game of “curdled milk”.’24 This unhappy vignette is quickly superseded and obscured by specialist languages of power and knowledge – law, medicine and technology – orientating around the politics of gender. The text becomes, to use its own words: ‘a digression, a refinement, a tactical diversion in the great process of transforming sex into discourse.’25 This screening of the sexual anatomy, act (‘caresses’) and emissions (semen called ‘curdled milk’) provides a telling parallel to their absence in critical commentaries on Lorenzo and Isabella and The Bridesmaid.26

In the twenty-first century Pre-Raphaelitism has been discussed as a movement that challenged and changed the dominant conventions of its age.27 Most of the discussion of explicit content has focused on the bohemian counter-culture, the circle of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the later Aesthetic Movement of the 1860s onwards,28 but art historian Elizabeth Prettejohn has suggested that the sexuality in Millais’s work might also be ‘difficult to reconcile with our conventional preoccupations with the Victorian’.29 Empirical studies of Victorian sexual practices have also revealed a more heterogeneous landscape, inconsistencies between ‘conventional preoccupations’ and a range of actual ideas and behaviour.30 Nineteenth-century technical, historical and social transformations in general are now understood to have produced ideologies that were equally fluid and unstable.31 A series of monographic exhibitions including Tate Britain’s Millais in 2007, have, moreover, re-introduced the particularity of the artist’s vision into discussions of Victorian art.32 There is scope, therefore, for seeing Millais’s sexual iconography through more mutable gender codes and other codes altogether.

The works in this essay depict single enclosed figures anticipating future fulfilment. For each, an intense imaginative visualisation of a longed-for loved one brings about physical realisation. Although the pictures can be read on many levels, two important themes are the analysis of desire and the relationship between mind and body, art and life. It will be argued that Millais did indeed ‘better’ Hogarth, evolving a language of sexual anatomy and activity that transcended caricature to explore these existential themes. All but one of the works fall between 1848 and 1854, experimental years that coincided with Millais’s participation in the Pre-Raphaelite’s rebellion. Art historian Jan Marsh has pointed out that as radicals, artists and very young men, the group was by no means aligned with the mores of their middle class: ‘Both physical impulses and romantic love were urgent and socially present issues.’33 1848 to 1854 happens to be the period when Millais negotiated sexual maturity, love and marriage between the ages of nineteen and twenty-five. As the perspective of this essay is not biographical, there is no need to rehearse the well-trodden tale of Millais’s unusual courtship with Effie Gray while she was married to his patron, the art critic John Ruskin, other than to draw attention to its departure from convention.34

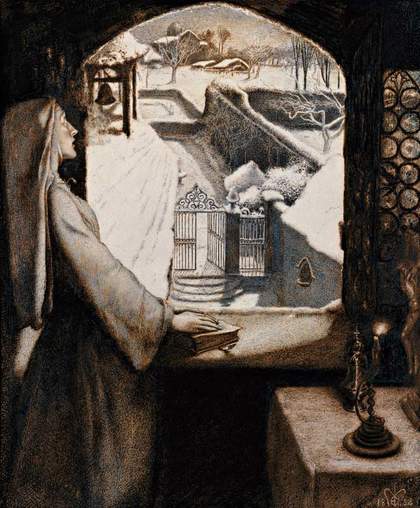

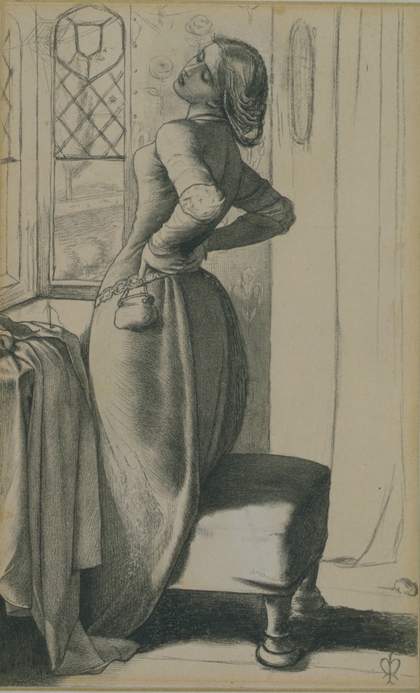

The pivotal image in this essay may at first be a surprising one, Millais’s neglected drawing St Agnes’s Eve 1854 (fig.6), based on Alfred Lord Tennyson’s 1837 poem of the same name. It is highly finished in pen and sepia ink with green wash, and shows a nun looking through a window at a snowy landscape partitioned by walls and gates like a medieval illumination.35 Beside her is an altar-like table covered with a white cloth on which sits a candle and a crucifix. The object that appears as a caster in The Bridesmaid plays the role of an incense burner or censer. The significance of the image is underlined by the fact that Millais gave it to his future wife, Effie, during the most difficult months between their emotional attachment and the annulment of her marriage to Ruskin on the grounds of non-consummation.

Fig.6

John Everett Millais

St Agnes’s Eve 1854

Pen and sepia ink and green wash

248 x 210 mm

Private collection

The nun is different from Millais’s other female figures. The particular interest of this drawing is that there is good evidence that it is a self-portrait. Curator Malcolm Warner relates the picture’s ‘mood of frustration and longing’ to Millais’s attraction to another man’s wife.36 Effie went further in a letter to her mother: ‘[It] is the most touching thing you ever beheld. Saint’s face looking out on the snow with the mouth opened and dying-looking is exactly like Millais’ – which however, fortunately has not struck John [Ruskin] who said the only part of the picture he didn’t like was the face which was ugly … I think I see Millais reading the poem to me and talking about it with me.’37 Effie’s words are confirmed by a comparison with William Holman Hunt’s portrait of Millais painted a year earlier 38 . Its aquiline profile and slightly elongated chin are ‘exactly like’ those in St Agnes’s Eve.

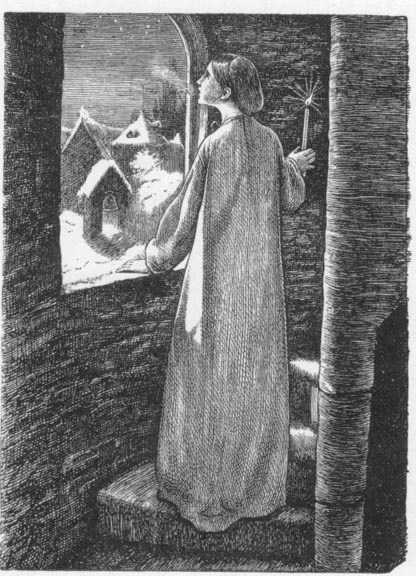

Fig.7

John Everett Millais

Illustration for ‘St Agnes’ Eve’ 1857

Engraved by Dalziel Brothers

Reproduced in Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Poems, London 1857

Effie’s letter stresses the discursive connection between Millais’s picture and Tennyson’s poem, remembering Millais ‘talking about it with me’. As Ruskin wrote to Tennyson in a letter about Pre-Raphaelite ‘illustrations’ for the 1857 Moxon editions of his work, ‘good pictures never can be; they are always another poem’. (fig.7)39 Scholarship has dispelled the myth that Millais rarely read and has traced sophisticated responses to literature.40 The curators Jason Rosenfeld and Alison Smith, in their catalogue for the 2007 Millais exhibition, analyse the artist’s absorbed figures as explorations of broader themes and images of Romantic and post-Romantic poetry.41 The figure of St Agnes unites several of these. She was, according to The Golden Legend, a young Roman girl who was tortured and killed when she refused to marry, sacrifice to pagan gods or submit to rape. Instead she chose to die and become a bride of Christ.42 The night before her death, 20 January, became associated with maiden rituals aimed at conjuring a vision of a husband. It was this folk custom, its mix of a perceptual, emotional and sexual rite of passage, which caught the nineteenth-century imagination. It synthesised transcendent experiences of eroticism, love and vision.

St Agnes was famously combined with Shakespeare’s lovers from feuding families in Romeo and Juliet to inspire Keats’s poem The Eve of St Agnes (1820). Here a young girl called Madeleine leaves the feast day revelries to perform her prayers to the saint and retire to bed. Madeleine’s lover, who her family have proscribed, has stolen into her chamber. As she sleeps he enters her bed and her vision becomes flesh:

Ethereal, flush’d, and like a throbbing star.

Seen mid the sapphire heaven’s deep repose;

Into her dream he melted, as the rose

Blendeth its odour with the violet.43

Afterward the couple escape together. Seventeen years after Keats’s poem was published, Tennyson’s wintry St Agnes’s Eve (1837) responded to the chilly setting of the first verse. It synthesised physical and spiritual consummation in a different way. A nun welcomes death and a longed for union with her bridegroom, Christ.

Keats’s The Eve of St Agnes was popular among Millais’s circle.44 In 1849, William Holman Hunt’s first painting on Pre-Raphaelite principles was The Flight of Madeleine and Porphyro During the Drunkenness Attending the Revelry 1848–9 (Guildhall Art Gallery, London). In 1850, Elizabeth Siddall took up Tennyson’s nun in a watercolour The Eve of St Agnes (Wightwick Manor, Wolverhampton). This work, along with Millais’s 1854 drawing and his preparatory sketches and final engraving for the 1857 Moxon print concentrate on Tennyson’s lines:45

Deep on the convent-roof the snows

Are sparkling to the moon

My breath to heaven like vapour goes:May my soul follow soon!

The shadows of the convent-towers

Slant down the snowy sward,

Still creeping with the creeping hoursThat lead me to my Lord:

Make Thou my spirit pure and clear

As are the frosty skies,

Or this first snowdrop of the year

That in my bosom lies.46

Millais’s St Agnes’s Eve was therefore a continuation of a visual and literary conversation with at least five other texts. It dwells on the dissolving of bodily boundaries that Keats’s and Tennyson’s poems have in common. As the nun stands on the threshold between shadow and light, misty breath links her form to the upward sweep of snow and sky punctured by the synaesthetic black toll of the funeral bell. This ‘blending and flowing’ of forms is, as literary critic Elizabeth Wright has noted, a feature of Millais’s work.47

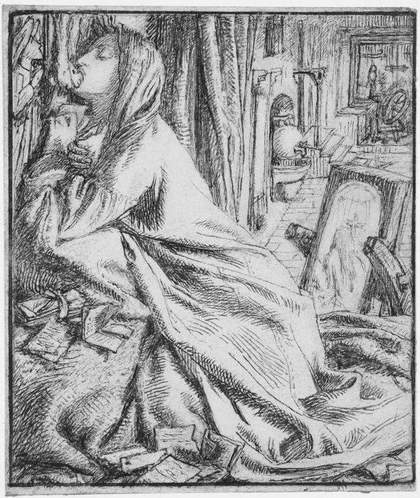

Fig.8

John Everett Millais

The Eve of St Agnes 1850

Oil on board

1841 x 1715 mm

The Maas Gallery, London

The centrality of the St Agnes theme to Millais’s artistic program between 1849 and 1854 is underlined by the frequency with which he reworked it. Two oil paintings return to Keats’s version of the poem. These are both titled The Eve of St Agnes, one from 1850 (fig.8) and a later larger version from 1863.48 They show Madeleine undressing, lost in reverie as she anticipates the dream of her future husband:

Anon his heart revives: her vespers done,

Of all its wreathed pearls her hair she frees;

Unclasps her warmed jewels one by one;

Her rich attire creeps rustling to her knees:

Half-hidden, like a mermaid in sea-weed,

Pensive awhile she dreams awake, and sees,

In fancy, fair St Agnes in her bed.49

Madeleine takes on the shape of a mermaid or budding flowers that also populate Keats’s poem. She rises, unsheathed as though from a cocoon, from her heavy robe. Millais explores the visual and visionary aspects of the scene by washing the room in the coloured shadows shed by the moon through the stained glass:

And diamonded with panes of quaint device,

Innumerable of stains and splendid dyes,

As are the tiger-moth’s deep-damask’d wings;

And in the midst, ‘mong thousand heraldries,

And twilight saints, and dim emblazonings,

A shielded scutcheon blush’d with blood of queens and kings.Full on this casement shone the wintry moon,

And threw warm gules on Madeline’s fair breast,

As down she knelt for heaven’s grace and boon;

Rose-bloom fell on her hands, together prest,

And on her silver cross soft amethyst,

And on her hair a glory, like a saint:

She seem’d a splendid angel, newly drest,

Save wings, for heaven: – Porphyro grew faint.50

Rosenfeld has commented on the way that Millais adapted watercolour techniques to oil to achieve this newly ‘ethereal’, dissolving quality that became important to symbolist artists and writers in Britain and France (Millais re-painted the 1863 version in watercolour itself, now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford).51

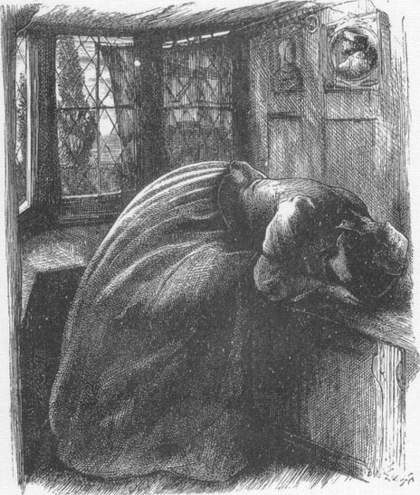

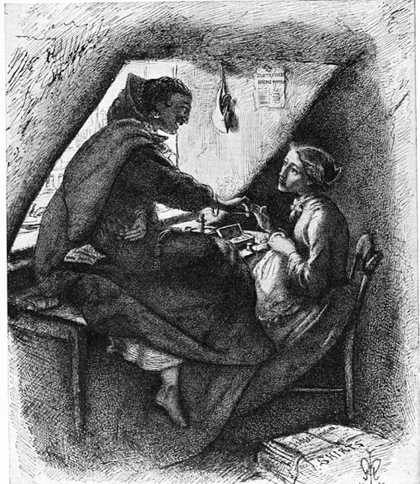

Fig.10

John Everett Millais

Illustration for ‘Mariana’ 1857

Engraved by Dalziel Brothers

Reproduced in Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Poems, London 1857

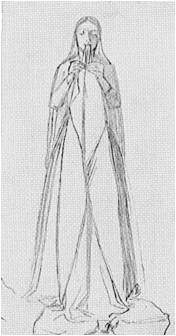

Fig.11

John Everett Millais

Study for Mariana 1850

Pen and ink

Victoria and Albert Museum

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Fig.12

John Everett Millais

Virtue and Vice 1853

Pen and ink

Photograph George P. Landow

Malcolm Warner has suggested that The Eve of St Agnes from 1850 was part of a plan to pair it with Lorenzo and Isabella.52 Millais’s realisations of the St Agnes poems have, as Alison Smith has pointed out, close compositional and thematic affinities to other contemporary representations of yearning figures at windows and mirrors including The Bridesmaid and an oil painting, an engraving and several studies all entitled Mariana (figs.9, 10 and 11).53 These relate to three Tennyson poems: Mariana (1830), Mariana in the South (1833) and The Princess (1847). The Mariana of the first two poems refers to the abandoned bride-to-be in Shakespeare’s play Measure for Measure (c.1603–4). Tennyson focuses on her longing and ennui by placing her in a similar but more drawn-out seclusion to Keats’s Madeleine, reiterating the contrast between chilly outer world and intimate interior. Mariana in the South describes the same heroine praying, and includes Keats’s sacramental accessories and stained glass. Tears, Idle Tears, a popular song based on lines from canto IV of The Princess, added regret to loss and longing:

In looking on the happy autumn-fields,

And thinking of the days that are no more.

… The casement slowly grows a glimmering square;

So sad, so strange, the days that are no more.

… Deep as first love, and wild with all regret;

O Death in Life, the days that are no more!54

These related pictures are connected by the silver vessel. The object itself was probably an eighteenth-century caster used for sugar, salt or spices.55 It first appeared as the phial of poison in The Last Scene from Romeo and Juliet 1848 (Manchester Art Gallery) and recurs in 1851 as a sugar caster in The Bridesmaid and as a censer or incense burner in the Mariana oil painting, as well as a censer in the St Agnes’s Eve self-portrait. In each case the object is presented on an altar, or altar-like table, with a white cloth. The 1863 oil The Eve of St Agnes replaces it with a gleaming silver box.

Whether or not this set of works constituted a deliberate decision to produce images in a series, it suggests a concentrated enquiry into the Romantic notion of the sexual subject in a later mid-century context. Feminist and Foucauldian readings of these cloistered figures characterise them as masculine fantasies of a feminine other excluded from the active world. For art historian Marcia Pointon, ‘the bridesmaid, hopeful of sexual union, Mariana, wearily and hopelessly awaiting it, and the nun having abandoned it’ are all incapacitated by their virginity, unmarried status and inability to procreate.56 Their sexuality is thus symbolic expression of gender polarity: ‘boundaries between marriage and non-marriage, celibacy and sexuality, woman and girl, are repeatedly invoked. Here the phallic law is at its most powerful … depictions of women defined by the invisible or symbolically present male, the other.’57 Pointon identifies the casters in each picture as unconscious, abstract symbols of ‘phallic authority’.58 The contained chastity of the figures – romantic fidelity in the case of Mariana and Madeleine and religious fidelity in the case of the nun – can be interpreted as a response to social worries about the unwed.59 The occupation of seamstress, for example, identified by journalist and social reformer Henry Mayhew as the last defence of the unmarried and unsupported women, was the standard trope for feminine labour, popularised by Thomas Hood’s The Song of the Shirt (1843).60 Mariana recalls a range of seamstresses in Victorian art and literature that responded to anxieties about women who worked.61 Her embroidery would have been recognised as different from the industrial-scale stitching depicted in the many poems and pictures on this theme, such as Millais’s own Virtue and Vice 1853 (fig.12), where a woman at a window is shown choosing between sewing and sex work. Mariana’s more genteel pastime reinstates the reassuring convention that had naturalised male economic activity in the outside world as different to female domestic practice.

However, such readings are limited by their unitary nature. Different women and men produce identical definitions of womanhood and manhood. The autumnal setting of Mariana and the frozen landscapes of both versions of St Agnes’s Eve tend, for example, to be uniformly read as references to virginal sterility.62 The orange blossom in The Bridesmaid, the snowdrops in the stained glass in Mariana and St Agnes’s Eve and on the nun’s breast are correspondingly interpreted, like St Agnes herself, as signs of virginal chastity.63 Other commentators, for example the art historian Paul Barlow, have detected a less definitive ‘tension between emotional intimacy and physical restraint’ in these works.64 Orange blossom can also stand for marriage and fertility.65 Mariana’s snowdrop is, unlike the nun’s, broken.66 The autumnal decay of her setting is not the same as the wintry death of St Agnes’s Eve; her over-ripe curves are distinct from the empty, tented drapery of the nun.67 Millais’s multiplication and subtle variation of similar figures, themselves revisions of imagery found in many texts by others, suggests that their content is restless.

Most restless, of course, is the ambiguous artist/nun of St Agnes’s Eve. S/he blurs male and female purity and suggests other sexual models. In 1995, James Eli Adams’s book Dandies and Desert Saints: Styles of Victorian Manhood demonstrated a nineteenth-century ideal of masculine sexual continence that developed alongside female chastity. As the economic unit transferred from land to people, the struggle for autonomy created a ‘technology of the self’, one aspect of which was gender.68 In the wake of the political scholar Thomas Malthus’s warnings about population, male continence answered middleclass anxieties about the need to defer procreation until it could be accommodated within the secure financial setting of marriage.69 These concerns would have been pertinent to a young artist who chose to gamble with his career and status first by joining the Pre-Raphaelite rebels and then by falling in love with the wife of a better established man (not to mention a leading art critic). Historian Herbert Sussman’s book Victorian Masculinities: Manhood and Masculine Poetics in Early Victorian Literature and Art (1995) presented Millais’s later academic career as just such a project of professional self-fashioning. Sussman sees his Pre-Raphaelite period as an enactment of a reclusive model: a ‘Carlylean belief that the sexually repressed life figured by the cloister could bring order and health to the psyche’, as opposed to the heterosexual exchange, commercial industry and domestic responsibilities of the Victorian norm.70

These ideas inform Lorenzo and Isabella and St Agnes’s Eve. Keats’s poem Isabella or The Pot of Basil was a condemnation of nineteenth-century class division and mercenary capitalism.71 In it the brothers treat bodies, even their marriageable sister’s, as commodities. Millais’s painting was exhibited with verses 1 and 21, concluding:

When ‘twas their plan to coax her by degrees

To some high noble and his olive trees.72

Isabella’s affection for their employee Lorenzo is intolerable. Victorian association of, and anxieties about, fiscal and sexual continence provide a context for the impatient spill of salt. The brother’s grip on the nut-cracker that casts the shadow, and the position of his other hand cupped below it (failing to catch the fragments of nut), recalls the gesture of masturbation (fig.3).73 Both motifs draw on a growing popular discourse during the nineteenth century about onanism and the resultant dangers of involuntary ejaculation, described in popular and specialist medical textbooks as ‘spermatorrhea’.74 The implication that Isabella’s brother is ungoverned, impetuous, driven by his appetites, adds a sly, pictorial twist to the poem’s critique of the middle-class marriage conventions that set gain above love. It picks up on Keats’s ‘ironic’ critique of romance through autoerotic imagery.75 Isabella exhibits equivalent tendencies to her brothers. Her autoerotic obsession with Lorenzo’s decapitated head, loved ‘more fervently than misers can’, provides a second conflation of unbridled economic and sexual lust.76

Adams and Sussman were part of a broader trend to reject ideas of a single normative manhood in favour of more nuanced and multiple masculinities.77 Queer theory is another example; Pointon recoups the masculinity of Millais’s ambiguous figures by raising the possibility of homosexual relations between him and William Holman Hunt.78 With this multiplicity, however, comes uncertainty. Sussman asserts that Millais’s depictions of doomed, effeminate, monastic types, are evidence of discomfort with the monastic role. This reading implies that the St Agnes’s Eve self-portrait constructs its critique of heterosexual norms of Victorian manhood as itself unmanly.79 Adams concurs and makes the point that as identities became more fluid they also became more contested: ‘momentous transformation of economic possibility … incited increasingly complicated and anxious efforts to claim new forms of status and to construct new hierarchies of authority.’80 He goes on to note, moreover, that ascetic models depended on a performance of self-integrity and suffering that was paradoxically theatrical, self-conscious and possibly artificial. He terms this ‘virtuoso asceticism’. Millais’s ‘dressing up’ in St Agnes’s Eve chimes with Adams’s idea of the ‘dandy saint’. Tennyson’s In Memoriam (1850) displayed similarly paradoxical ‘parades of pain’ and also adopted a female voice to do it – ‘his culture’s most powerful emblem of emotional integrity’, as Adams puts it.81

This insistent presence of the masculine in depictions of the feminine and the feminine in constructions of the masculine suggests that there is potential to think beyond the binary altogether. Even writers who admit a repertoire of gender models continue to define them in a binary way, however, perpetuating the nineteenth-century ‘images of male power and the norms of manliness’ that they critique.82 In the case of Victorian art the phenomenon is compounded by a kind of anti-canon, a set of works regularly presented for the purpose of demonstrating an ‘other’ set of gender rules.83 As Elizabeth Prettejohn observes, detecting sexual codes in works of Victorian art may ‘substitute contempt for approbation’, but the practice leaves the polarities themselves – victim/oppressor, scandalous/respectable, artist/model – intact.84 The ease with which such meanings in Pre-Raphaelite paintings are able to be decoded ‘seems to prove that misogyny is their problem not ours’, but in fact suggests otherwise.85

St Agnes’s Eve brilliantly exposes the critical parallax implicit in discussions of gender based on this binary model. The option of designating Millais’s nun as either a man or a woman unmasks the prerequisite that it has to be designated at all. Every discussion of sexuality is launched by a nomination of gender. While Foucault and others demonstrate that, in theory, gender is not essential but a product of history and discourse, St Agnes’s Eve shows that, in practice, narratives of sexuality involve a gender assumption that is privileged as ahistorical and outside the discourse. The possibility of applying two genders to St Agnes demonstrates how each renders one set of meanings visible and another set invisible. Effie’s letter, for example, reveals that her evaluation of the painting as a male was different from Ruskin’s, who saw the figure as female. Furthermore, a sexual polarisation (the exclusion of masculine characteristics in order to read the figure as female or vice versa) is easily displaced into other oppositions such as victim/oppressor or passive/active, which shy away from sex itself.

A relaxation of notions of difference in favour of a more elastic approach to gender and subjectivity might preserve the insights of existing criticism but undo the ideological closures, the sexual turning away, that it has bought about.86 Pointon and Adams provide a basis for this in their exploration of multivalent identities within genders. Pointon, for example, offers a kind of composite: ‘the idea of the nun is’, she says, ‘not in opposition to matrimony but inscribed within it. The nun enables concepts of virginal timelessness to survive within the ideal of marriage’.87 St Agnes’s Eve, for example, combines Millais’s ‘image and that of Effie in a representation of frozen chastity, a sort of negative union’.88 A glance at the series of pen drawings made by Millais in 1853 dramatises this. Their lighter play on gender pre-empts the more serious self- portrait. One shows Effie in the same pose as the nun looking through a window onto a landscape.89 In another, it is Millais that is enclosed in a bedroom, displaying his Vitruvian proportions.90 A more finished drawing of Millais and a fellow artist smoking to keep away midges provides a surprising source for the misty exhaled breath of the nun (Awful Protection Against Midges 1853, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven). The most unexpected depicts Effie and Millais in a chamber together. As well as the window, a closed door signifies privacy. She stands, cutting his hair. He sits modestly clutching a cloth about his shoulders. His other hand bandaged and a plaster across his wounded nose.

Literary historian Kate Flint sees the unstable and performative nature of nineteenth-century sexual identities as a possibility rather than a problem. She modifies conventional characterisation of the Romantic and post-Romantic creator as a kind of ‘super subject’ and describes instead a flexibly gendered voice: ‘[The nineteenth-century women poet is] not primarily concerned to draw on some stable sense of self out of which to write, but uses her verse as a means of exploring the fact that identity may be something imaginatively, generously, experimentally dispersed.’91 Millais’s figures can be seen as similar experiments with multi-gendered, subjective models, a pictorial equivalent of ‘writing and reading which can stretch both writer and reader well beyond the bounds of personal experience’.92 This important idea of gender as device rather than definition – as a means of exploring, extending and sharing subjectivity – blurs the binary model. It allows St Agnes’s Eve to become an instance not of problematic masculinity or of femininity, but a play on and from all of these.

These experiments in synthetic subjectivity reflect, as Flint suggests, on the painter’s gaze. The figure at a window is a motif par excellence for an artist negotiating exchanges between inner and outer, imaginative and real vision, which are central to the poems by Keats and Tennyson that inspired the pictures.93 Economic, class and gender struggle are evaded through an exploration of absorbed, agile, self-sufficient, outsider vision informed by desire, love, memory and superstition or faith. The male nun in Millais’s St Agnes’s Eve and the contemporary curate in his Married for Love 1853 (British Museum, London), no less than the female Madeleine, Mariana and the bridesmaid, examine aspects of agency that are socially disengaged. The repetitive, industrial quality (‘Stitch! Stitch! Stitch!’) 94 of the sewing in Virtue and Vice, for example, contrasts with the individual nature of Mariana’s embroidery to make a distinction between creative and non-creative work without the gender difference usually associated with these two categories.95 The trope of tapestry as feminine creativity can be understood as an analogy for a painting technique usually seen as male labour.96 Millais’s prismatic paint strokes imitate the accumulation of coloured threads (Millais and his associates sewed props for their medieval settings).97 Female imprisonment also explores the practice of the male artist – his quiet occupation transcribing each fold and floorboard. The Pre-Raphaelite method of working on location and sur le motif placed the artist alone for long periods in the very spaces in which they depicted their solitary figures. Millais shared his characters’ fixation on ordinary domestic objects and framed views, and their sensitivity to waning light.

Fig.13

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Illustration for ‘Mariana of the South’ 1857

Engraved by Dalziel Brothers

Reproduced in Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Poems, London 1857

Once Millais’s waiting figures are accepted as synthetic subjects, their sexuality can be understood as a vehicle for facets of artistic experience other than gender. Literary historian Isobel Armstrong argues that creative vision is explored in the Pre-Raphaelites’ writings through an intersection of the ‘sexual and the visionary’, which she expresses as ‘sacramental eroticism’.98 The Maryan accessories of Mariana, her blue robe and the stained glass as well as her oratory, or ‘idolatrous toilet table’ as John Ruskin called it, parallel this tendency.99 They draw on the ritual imagery of Tennyson’s more overtly religious and sexual sequel to Mariana, Mariana in the South, who is described praying at an altar.100 Mariana in the South is more focused on vision and desire than Mariana and reprises both the intensely sensed medieval setting of Keats’s The Eve of St Agnes and its imaginative summoning of a vision. Rossetti, rather than Millais, illustrated the poem for Moxon (fig.13). Millais’s The Bridesmaid, however, anticipates both Rossetti’s depiction of the heroine praying at the altar and the intimate loose-haired format that would become the hallmark of his later Aesthetic work.

Fig.14

John Everett Millais

Study for Mariana 1850

The Bridesmaid stands in similar relation to Millais’s earlier Mariana as Tennyson’s Mariana in the South stands to his poem Mariana. A symmetrical Study for Mariana 1850 very like The Bridesmaid confirms that she is a variation of the Mariana theme (figs.14, 2). The bridesmaid is a modern figure, but like Mariana in the South and Madeleine, she is absorbed in a ritual aimed at apprehending her lover. Her activity – passing a piece of the wedding cake through the wedding ring nine times on St Agnes’s Eve – connects her to Millais’s The Eve of St Agnes and St Agnes’s Eve.101 The silver caster on the table at which the bridesmaid enacts her ritual occupies the position of the censer (the same object) on Mariana’s altar, so it is as though we are looking at Mariana as she prays.

Like Madeleine, Tennyson’s Mariana in the South succeeds in summoning a vision of her saint, in this case the Virgin Mary. Where Madeleine’s dream saint blends into her actual lover, however, Mariana’s is superimposed onto her own body, her reflection seen in a mirror as she worships. It recalls the earlier moment in Keats’s poem when Madeleine’s body is superimposed with the figures cast by the stained glass. Tennyson’s description of this mirror image fits the intimate frontality of both Millais’s Study for Mariana and The Bridesmaid:

She, as her carol sadder grew,

From brow and bosom slowly down

Thro’ rosy taper fingers drew

Her streaming curls of deepest brown

To left and right, and made appear,

Still-lighted in a secret shrine,

Her melancholy eyes divine …

And on the liquid mirror glow’d.

The clear perfection of her face.

‘Is this the form’, she made her moan,

‘That won his praises night and morn?’102

The shining, glassy surfaces of the hair, fruit, ceramic, silk and skin of The Bridesmaid give the sense that she is a reflection. This ‘liquid mirror’, as Tennyson called it, complicates and layers vision like tears. The poem combines the two in the same way as the shining eyes of the bridesmaid hint at both their moisture and the glass surface in which they are reflected, lending it similar levels of reality and dream. In addition to this, the bridesmaid comes in and out of focus as we see her as figure and as reflection on a glass surface. As this happens, so the viewer wavers from sharing the point of view of the male lover to sharing that of the reflected bridesmaid herself. This finds its corollary in the mixing of the real and imagined face. It looks forward to Millais studying his own reflection in a mirror as he re-imagines it as the nun in St Agnes’s Eve. This synthesis of female and male, real and imagined bodies images the synthetic subjectivity of the artist. Elizabeth Wright’s sense of the instability and permeability of objects in Millais’s paintings ‘blending and flowing’ extends to subjects too.

The effect of ‘blending and flowing’ also expresses the operations of desire.103 The arid desert setting of Mariana in the South articulates sterility without the decay of autumn in Mariana or the frigidity of the snow in St Agnes’s Eve. In the poem, hot, dry claustrophobia is haunted by liquid day dreams such as the one above, imaged in the rapt expression, moist eyes, lips and skin of The Bridesmaid. These are realised in a release of tears in the climax of Tennyson’s poem, a sultrier restaging of the conclusion of his earlier St Agnes’s Eve:

At eve a dry cicada sung,

There came a sound as of the sea;

Backward the lattice-blind she flung,

And lean’d upon the balcony.

There all in spaces rosy-bright

Large Hesper glitter’d on her tears,

And deepening thro’ the silent spheres

Heaven over Heaven rose the night.

And weeping then she made her moan,

‘The night comes on that knows not morn,

When I shall cease to be all alone,

To live forgotten, and love forlorn.’104

The visual and sexual climax of Tennyson’s heroine is different from Keats’s Madeleine’s. There is no real male lover, she sees only herself. This autoerotic encounter fits the activity of The Bridesmaid placing the cake within the ring, and Study for Mariana biting the drapery, and again looks forward to later Aesthetic imagery.105

Rossetti’s description of the artist Chiaro’s autoerotic encounter with his own soul in ‘Hand and Soul’, published in the Pre-Raphaelite journal in 1850 just before The Bridesmaid was painted, is like Mariana in the South’s encounter with her saint/face. It intensifies Tennyson’s deliquescent imagery through a similarly sensual device to the one found in Millais’s picture. Rossetti dissolves the boundaries between figure and viewer, bringing him/her close enough to touch and taste the enveloping hair: ‘And Chiaro held silence, and wept into her hair which covered his face; and the salt tears that he shed ran through her hair upon his lips; and he tasted the bitterness of shame.’106 This bringing near again reiterates Pre-Raphaelite artistic practice, the singularly long, close and restricted focus on each individual object and body part. The interchangeability of Tennyson’s and Rossetti’s salt tears with other bodily fluids alerts us to one of the outcomes of this intimate partitioning, the tendency for surfaces and objects to become detached from their surroundings and transposable, to suggest other surfaces and objects, as in the case of skin and glass.

The ‘bending and flowing’ from one image to another of phial/caster/censer with its contents of poison/salt/sugar/smoke is a pictorial equivalent of Rossetti’s poetic device. The dissolving quality complements Millais’s variation on Pre-Raphaelite technique in the paintings under consideration, applying oils like watercolours in veils of transparent colour, seen in the hair of the bridesmaid and in the even more ephemeral, underwater effect in both paintings of The Eve of St Agnes. The sex obscured by binary gender models and cultural assumptions becomes more conspicuous without them. New contexts are created for the silver vessels. The shiny metal of the salt cellar and the caster have generally been associated with masculine power and ‘violence’.107 The association of anxieties about sexual and financial incontinence, explored by Adams, brings into better, bitter view the phallic shadow and the spilt salt in Lorenzo and Isabella. They in turn make visible the seminiferous imagery of the contents of the other silver vessels in The Bridesmaid, Mariana and St Agnes’s Eve. Each of these varies to add further resonances.

Millais’s glittering caster cannot fail to evoke Keats’s strange image of the ‘throbbing star’ that brings Porphyro into Madeleine’s dream. The sharply three-dimensional rendering of the metal in The Bridesmaid, almost alive in the pronounced upward twist provided by the pattern, enacts a visual interruption of the soft hair that matches the bridesmaid’s rapt gaze as she passes the cake back and forth through the ring. It echoes the allusions to semen in hair that occur in Rossetti’s poetry, both in Hand and Soul, mentioned above, and in Jenny (1847).108 The vessel’s phallic presence as censer in Mariana (fig.9) transforms salt and sugar into smoke, associating sexual longing with the more abstract sensual experience of scent and the more ephemeral dreams and recollections that are the subject of the picture. Art historian Christina Bradstreet has shown that scent was associated, in the Victorian period, with the power of memory and its physical effects on the body.109 The candle above the altar burns steadily, softening the sharpness of the container into a swelling rather than a penetrating chiaroscuro. The modelling of the silver vessel is modified again in St Agnes’s Eve (fig.6). Here the candle gutters so the object is smaller and emaciated into fewer linear shadows. These match the thin figures of the nun and Christ on the little crucifix. The earlier associations are not lost, as Warner notes, but developed from a metaphor of luxurious longing to one of ascetic lack. Salt, sugar and smoke are substituted with pristine mist and snow.

The crucial point here is that ‘sacramental eroticism’ does not simply twin or oppose earthly and spiritual love, transgression and purity, incontinence and continence. Millais’s variations suggest a wealth of multivalent exchanges between all of these.110 As Elizabeth Wright explains in her perceptive reading of Millais’s Return of the Dove to the Ark 1851 (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford), objects in Millais’s paintings of this period ‘flow into and out of each other’s edges’ in the same way as they do in surrealist art.111 Salt, sugar and smoke and their silver containers evade oversimplified discourses of gender difference and instead enact an open-ended ‘play’, as Wright puts it.112

The sugar caster’s qualities of sharpness in The Bridesmaid are transferred, in Mariana, to the upright silver needle that she has jammed into the white flower in her embroidery in front of her, a subtle translation of Hogarth’s ‘mangled fowl, with a fork stuck in its breast’, remarked upon in contemporary texts about his painting The Orgy.113 The suggestive juxtaposition of the petals and the pin, with its trail of white thread, is even more pronounced in the more finished drawing Study for Mariana (fig.11) where a larger needle is plunged into corrugations of cloth. This labial form is reiterated in the wall-paper behind the figure where the pattern of roses gives way to a single orchid or iris-like bloom. Although the caster itself is absent, prominent in the window is the poplar tree described by Tennyson as standing out against the flat landscape. It troubled Mariana with a shadow cast ‘‘pon her bed, across her brow’, and is usually read by critics as a phallic presence.114

The sugar caster in The Bridesmaid is one of a series of upward curves beginning with the red rim of the plate and culminating in the profile of the girl. ‘Fear and fascination’, as observed by Barringer, reverberates through the entire scene. The rounded shape of the censer in Mariana echoes the rising, rounded figure of Mariana herself, sheathed in her glossy velvet robe. Concentric loops of hair weigh down and loosen their binding, rhyming with the not-quite-elliptical outline of the circular mirror seen on the wall from the side, rounded off into another phallic form. Mariana reprises the elongated profiles of Study for Mariana (fig.11) and of Madeleine in both oils of The Eve of St Agnes. All of these, like the bridesmaid, look forward to the concentric rhythms and phallic profiles of Edvard Munch’s solitary figures.

The two Madeleines in Millais’s The Eve of St Agnes are different from Mariana in that they burst out of the blue robes fallen at their feet. Protruding from the drapery like the needle from the cloth, they resemble both vulvic flower and growing phallus.115 Their hybridity expresses the mixed subjectivity of The Eve of St Agnes poem, the merging of Madeleine’s desiring gaze with that of Porphyro/the viewer who watches her, and the closer ‘blending’ that will take place in her bed. Male and female sexual anatomy is overtly united in the centrally tucked and pleated drapery of the frontal figure of Study for Mariana (fig.11). Its compositional affinity with The Bridesmaid adds a further layer to its simultaneity of male viewer/female reflection. In the 1863 version of The Eve of St Agnes, the silvered fabric of Madeleine’s dress condenses the body and the caster into one. This may explain why the vessel does not haunt the margins of this picture.116

To conclude, Foucault’s The History of Sexuality disseminated its themes throughout many disciplines and engendered an astonishing array of productive analysis. The turning away from the anatomy and act of sex itself, ‘caresses’ and ‘curdled milk’, made by polarised discourses of power and gender has, however, made it hard to see the exquisite poetry of the body in Millais’s art, or its precocious place in a wider post-Romantic, Aesthetic and symbolist visual and literary tradition.117 But it was not hidden. Armstrong stresses the intentionality of the disturbing, even ‘embarrassing’ content of Pre-Raphaelite writings and there is no doubt that the sexual imagery in earlier Pre-Raphaelite paintings is equally deliberate.118 Millais’s sophisticatedly inter-textual responses to the St Agnes story move on from Romantic eroticism and Hogarthian caricature. His nuanced variations explore restless, synthetic subjects, which are dialectical not binary. More importantly, they show a sexual imagery with implications beyond pornography, prurience or gender, expressing artistic and existential debates about individual and society, desire and dislocation, sight and insight.