The history of Nigerian modernism before 1960 – the year of Nigerian independence – is marked by an array of disjointed socio-political events and cultural developments, such as anti-colonial revolts, labour disputes, the foundation of Nigerian art education, as well as the establishment of diasporic networks and international gatherings of black writers and artists. These events intricately connect to a more fluent postcolonial discourse. However, without naming the forces of colonialism, it is impossible to fully describe the civil and epistemic disobedience from which the processes of decolonisation originated. The decolonial theorist Walter Mignolo has argued the need to examine what he terms ‘identity in politics’ in order to find a way out of the cycle of colonial logic:

Identity in politics, in summary, is the only way to think de-colonially (which means to think politically in de-colonial terms and projects). All other ways of thinking (that is, intervening in the organization of knowledge and understanding) and of acting politically, that is, ways that are not de-colonial, means to remain within the imperial reason; that is, within imperial identity politics.1

Fig.1

Portrait of Ben Enwonwu, undated

© Courtesy the Ben Enwonwu Foundation

What follows is an attempt to think de-colonially by reflecting on the identity in politics of the modernist painter Ben Enwonwu (fig.1). Enwonwu is an important figure in early Nigerian modernism because his works and his extensive archive of speeches, articles, letters and unpublished biographical writings offer an unprecedented insight into the mind of an African artist whose identity bifurcated in direct response to colonialism.2 Unlike the Franco-Caribbean theorist Frantz Fanon, Enwonwu did not set out to systemically analyse his findings. Instead, his archive reveals that he was compelled by his need to create freely and, by his personal conscience, to use his privileged visibility as an African artist to resist colonisation in public. He was by no means the only artist to have assumed this stance. At a time when the African voice was most dehumanised, his and many others narrated an alternative history to that propounded by universalist modernity.

The development of art in the Nigerian region at the turn of twentieth century typically follows two logical strands: one emerges from the renegotiation of a pan-African iconography, including prehistoric, Nok and Egyptian culture. The other strand emerges from intermittent contacts with the West. Through trade encounters and colonialism, hybridised practices took hold.3 In Britain, modernism is seen to have fully developed by the 1930s, in part through encounters with European movements in Italy, France and Germany. By extension, the modernism of the British-educated Enwonwu – and in particular the work he made between 1939 and 1967, his most renowned productive phase – is visually recognisable as an example of the universalist canon of modern art. Similar ties to this canon can be identified in the photography of Jonathan Adagogo Green from c.1887, Aina Onabolu’s European-style painterly figuration, Akinola Lasekan’s paintings and political cartoons, Felix Idubor’s sculptural works, and the gradual abstraction of Clara Ugbodaga-Ngu. With the exception of Green, who was taught photography in Sierra Leone, and Lasekan, all these artists attended London art schools and made work that merged their stylistic negotiation of European techniques with African subject matter and regional iconographies.

Beyond the reflection of cultural contact, some of these artists also negotiated their personal positions in relation to the Western claim that the African culture was inferior. The dismissal of their artistic agency based on contact with Western education and technical advances assumes a top-down exchange with a superior European knowledge base. The stylistic duality or innovative hybridisation this contact initiated is marked as either colonial infection on the one hand, or colonial exception on the other, depending on the viewpoint. This reading, which is pervasive even in decolonial accounts, positions the colonised subject as a static actor in a non-negotiable past or, alternatively, too complex to renegotiate. It largely disregards personal initiative, self-funded education abroad, cross-cultural self-reflection or mentoring and peer-to-peer support, as exemplified by Onabolu’s instruction of Lasekan, Enwonwu’s encouragement of Idubor, or Ugbodaga Nugu’s support of Enwonwu’s pan-Africanism.4

An entire generation of early Nigerian modernists is only partially accounted for through selected monographs published over the past decade.5 However, if we observe the practice of leading artists born between 1870 and 1930 in context, it presents a congruent negotiation of Nigerian regional and collective culture with European subjective academic styles and technology. This period, which is rich with various stylistic explorations of indigenous and encountered cultures, is concurrent with the interest developed by European modernists in African and Oceanic art. Even if we cannot speak of a Nigerian modernist movement, as no such self-definition or association appears to exist, the hybridised works are nonetheless part of the canon of modernity. The definition of a ‘colonial modernism’ as a peripheral exception and, qualitatively speaking, less modernist, effectively renders it ‘absent’ from the canon of modernism. Instead we need to define it as a locally specific modernism in order to reassert its manifestation on an epistemic level. The retrospective application of Boaventura de Sousa Santos’s sociology of absences would be one way of underpinning such an endeavour: ‘To be made present, these absences need to be constructed as alternatives to hegemonic experience, to have their credibility discussed and argued for and their relations taken as object of political dispute.’6

Enwonwu’s identity in politics

Odinigwe Benedict Chukwukadibia Enwonwu, also known as Ben Enwonwu, developed a modernist practice from the mid-1930s onwards. His rise to international fame during the late 1940s and early 1950s, coinciding with colonial rule in Nigeria, was phenomenal. He may have been a reluctant agitator in a politically charged time, but he nonetheless articulated what many of his contemporaries felt, and he made himself heard in a global setting. In 1956, at the First International Conference of Negro Writers and Artists in Paris, he declared that: ‘The problems which face the African artist of our generation are many and difficult. They may be classified as political, cultural, educational and social, and even emotional problems.’7

Fig.2

Photograph taken on the occasion of Nigeria joining the United Nations, showing Ben Enwonwu (centre right) with a Nigerian delegation that includes politicians J.M. Johnson (centre left) and Festus Okotie Eboh (third from left), United Nations General Assembly, New York, 1960

© Courtesy the Ben Enwonwu Foundation

The formation of Ben Enwonwu’s cultural identity and agency developed in two phases. The first was a phase of epistemic disobedience during the late colonial period from 1937 to 1956. This was marked artistically by an increasing integration of Igbo symbolism, first as content and later as iconography, and politically, in the form of contributions to Nnamdi Azikiwe’s West African Pilot, as well as ‘weaponising’ himself with his study of European art and anthropology and his encounters with black internationalism. The second phase, between 1956 and 1966, was characterised by his idealistic cultural pan-Africanism as articulated in letters and the demand for a non-aligned cultural policy of the sovereign state and his leadership of the cultural establishment for FESTAC 1966.8 A second cast of his work Anyanwu 1954–5 was handed to the United Nations as a gift when he attended the formal ceremony for Nigeria’s accession to the UN in 1960 (fig.2). In this goodwill gesture the Igbo iconography of this particular work was chosen as a symbol for national sovereignty.9

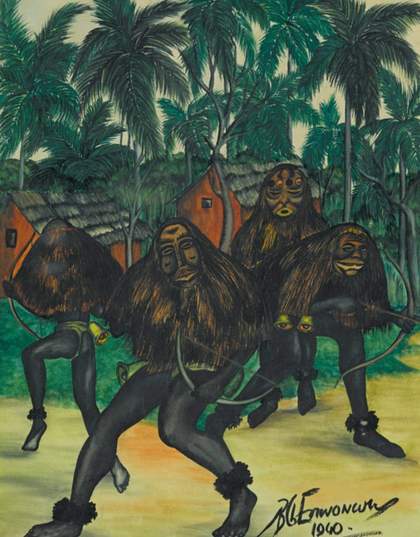

Fig.3

Ben Enwonwu

Ugala Masquerade 1940

Private collection

© Courtesy the Ben Enwonwu Foundation

Fig.4

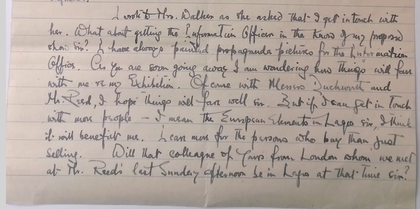

Ben Enwonwu, letter to his patron Lionel Harford, 16 January 1943

Courtesy Neil Coventry, Lagos

During the first phase Enwonwu initially embraced being patronised as an exemplary art student under colonial educational policy, and he fervently believed in becoming an art educator as a way forward. This belief informed his later position as a governmental advisor. The work he made during this time, which represent nature in a contrived indigenous style, encouraged by his British art tutor Kenneth Murray’s idea of ‘native’, was rewarded with extensive private and public British patronage as well as early commercial success. Despite the prescribed subject matter, such as local scenarios of houses and streets with palm trees and labourers and masquerades in village settings, he used a consistent stylisation of flat figures with strong abstracted outlines for small-scale paintings and sculptures from 1937 to 1941 (see, for instance, Ugala Masquerade 1940; fig.3). He quickly realised that he had outgrown Murray’s teachings and his friendship with his tutor became more antagonistic during his early twenties. His letters to patrons written between 1939 and 1943 reflect his keenness to progress commercially and socially, and he welcomed patronage to enhance his international reputation and further his education. During the Second World War Britain became more dependent on the resources and manpower from its colonial empire, and while Enwonwu never commented on or showed empathy with the British struggle, in 1943 he contributed works to the British Ministry of Information’s propaganda effort, which allowed him to gain access to more European buyers and sponsors (fig.4).10

Fig.5

Ben Enwonwu

Agbogho Mmuo 1949

Private collection

© Courtesy the Ben Enwonwu Foundation

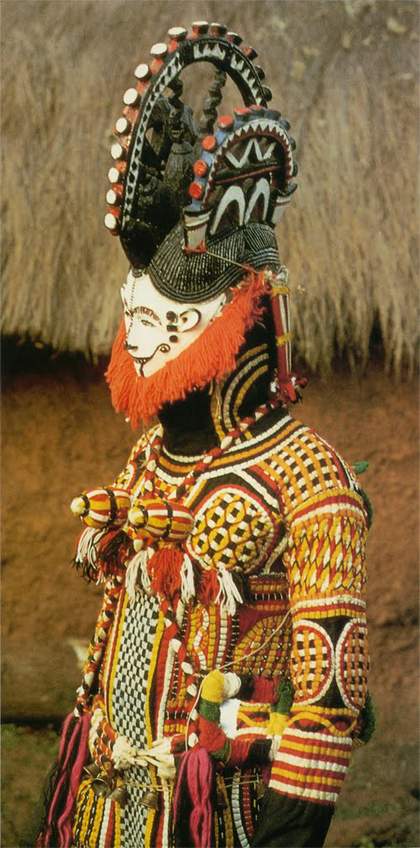

Fig.6

Igbo Agbogho Mmuo (Maiden Spirit) masquerade, Alaigbo, c.1934

G.I. Jones Photographic Archive of Southeastern Nigerian Art and Culture, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale

Enwonwu began painting in a European figurative style through his Aghbobo Mmuo series (Igbo masquerades) in the late 1940s (see figs.5 and 6). This represents the first instance of his coding of Western figuration with Igbo iconography. The way the mmuo are depicted marks a departure from his early paintings under Murray’s tutelage. These paintings and watercolours are highly personal, with an emphasis on the conjuring, magical force and idealised beauty of spirits. Following the masquerade motif throughout his practice reveals Enwonwu’s transition from depicting prescriptive scenes in the Murray years to claiming the iconography as an African self. The way the British commonly responded to spirit shrines was to dismiss them as juju, ban divination and destroy the oracles and shrines in documented actions.11 Enwonwu is not known to have reacted to any specific incident, but he was clearly aware of the institutionalisation of colonial iconoclasm as a practice and through dismissive language. In this respect the reintroduction of Igbo motifs into his work can be seen as a form of coded resistance. Art historian Nkiru Nzegwu, herself Onitsha-Igbo, has expanded on this in her 1998 essay ‘The Africanized Queen: Metonymic Site of Transformation’, where she argues that the mmuo motif later expanded into a range of Igbo signifiers.12 This appears to have continuously informed Enwonwu’s hybrid practice.

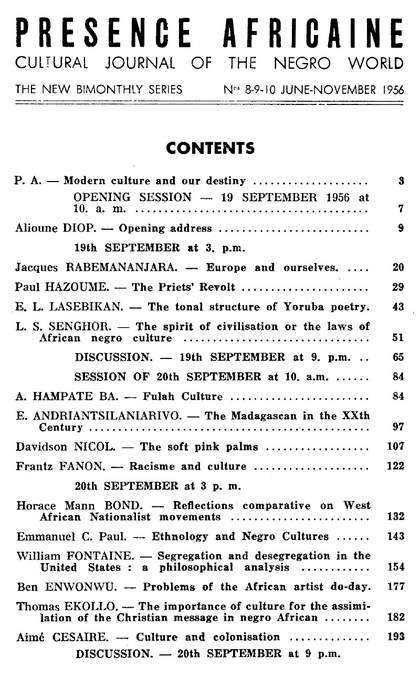

Fig.7

Contents page of the special issue of Présence Africaine featuring the proceedings of the First International Conference of Negro Writers and Artists, Paris 1956

It is clear from Enwonwu’s writing that he sought to break the identity construction devised by the colonial administration in order to adapt better. He seemed confident that British patronage would help him obtain equality among the Lagos socialites. While in London, where he arrived just before the war ended and where he experienced evacuation and rationing, he was keen to overcome the ‘colour bar’.13 In 1948, following his art diploma from the Slade School of Fine Art he chose to study anthropology, which speaks of his desire to understand the construction of identity under colonialism. Under Daryll C. Forde at University College London he was exposed to Western knowledge and identity construction first hand. Forde was a respected expert, especially on Nigerian culture, which constituted an interesting, multi-faceted encounter for Enwonwu.14 Through the complex experience of British and European selective racial segregation, Enwonwu became visibly politicised and actively sought agency. Strengthened by the background of Nigerian resistance, his friendship with the black intelligentsia in Paris, and his encounter of pan-African revolutionary organisations in London, he began to (re)activate his Igbo identity on his own terms. In 1956 he gave a simple, emotional speech to the First International Conference of Negro Writers and Artists in Paris (fig.7), which is also where Frantz Fanon first presented his findings on the ‘fossilisation of culture’ under colonialism in his special address ‘Racism and Culture’.15 Enwonwu spoke of the impossibility of ignoring the political upheaval of his time and a sense of duty as an artist to his origins:

I know that when a country is suppressed by another politically, the native traditions of the art of the suppressed begin to die out. Then the artists also begin to lose their individual and the values of their own artistic idiom. Art, under this situation is doomed. What follows is an artistic vacuum that may be prolonged for even a century. By this of course, I do not mean that no more art can be created by the artists, but much of what they could, and did do in the past, can be denied them and those who follow them.16

He came to this conclusion after spending twelve years in London and keeping a studio in Hampstead from 1944 while exhibiting in the US and Europe under British and American joint patronage. Enwonwu’s patronised privilege means that he was able to experience his African identity as both colonial subject and also as a traveller who traversed borders and saw himself from without.17 Enwonwu experienced the limitations and the potentiality of what it meant to be African. In 1946 he encountered the poet and theorist of Négritude Léopold Sédar Senghor when he participated in the Exposition Internationale at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris.18 Enwonwu kept contact with the West African Student Union (WASU), on occasion encountering Kwame Nkrumah, the future socialist leader of independent Ghana. He eschewed the communist and socialist debate in WASU, but felt drawn to the early debates around Négritude and décalage, and became an advocate of Senghor’s revival of African traditionalism instead. In a bid to reject colonialism he assumed the responsibility of affording equal agency to African artists. It is clear from his 1956 speech that Enwonwu was not a politician, but he nonetheless understood colonialism as a force that limits or impedes artistic creativity:

[I]t is a pity that while the historic influence of African Art on European aesthetic traditions and Art has created a healthy revitalization of decadent art-form and traditions of Europe and America, the influence of western ideas and technological system, as well as that of education has, politically speaking, not proved, and can never prove, the best means of keeping alive the native genius of the African peoples. And while Europe can be proud to possess some of the very best sculptures from Africa among museums and private collectors, Africa can only be given the poorest examples of English Art particularly, and the second-rate of other works of art from Europe.19

This fundamental inequality of exchange underpins today’s museum structures in the same way it did in 1956, despite the ambitions of some museums to decolonise their collections. The kind of art history that is most often applied institutionally lacks the theoretical frameworks to accommodate non-linear and multi-dimensional views of history.20 Enwonwu’s comments above clearly illustrate his understanding of the extent of institutionalised discrimination towards non-Western artists working within colonial structures. It also reveals his idealism. When he deplores the paucity of good art in Africa he is inciting his contemporaries to change the balance. It is also an unveiled critique of the British education system, which he reiterated in a radio interview with the BBC in 1958, and a clear recognition of the exploitative contract of colonialism.21

Fig.8

Ben Enwonwu

Anyanwu 1956

National Museum, Lagos Island

© Courtesy the Ben Enwonwu Foundation

Photo: Bea Gassmann de Sousa

As well as through speeches, writing and interviews, Enwonwu also drew attention to these issues in his artistic practice. His consecutive sculptures of the Igbo-influenced Anyanwu for the national museum in Lagos (fig.8) and the subtly Africanised portrait of Queen Elizabeth II were created in the years 1955–7.22 They reveal his struggle to free himself of identity construction and reinvent himself through hybrid styles, applying them ‘for purpose’. Indeed, these works can be understood as attempts by Enwonwu to utilise his indeterminate status as an integral part of the colonial structure in order to try and destabilise it from within.

Rather than assuming this to be the inevitable position to take in relation to the power imbalance of the colonial situation, real identity as opposed to constructed identity is of course far more complex. If we concentrate solely on a uni-dimensional identity model of the colonised, we sidestep the multi-dimensional reality experienced by Ben Enwonwu. He was Onitsha-Igbo and Nigerian, with an international education, accrued patrons and, by extension, financial success. He later established himself in the multicultural Yoruba city of Lagos and gained employment imbued with local power by the British colonial administration, which also allowed him to maintain contact with the pan-African and European liberal elite. It reveals the options that Enwonwu and many of his peers retained. While being tagged ‘native’ was a clear racist limitation, Enwonwu’s complex real identity afforded him unprecedented command of multiple social, cultural and religious platforms. However, we have to bear in mind that this optionality is a direct result of the alteration of cultural and social reality through colonialism. Optionality is not complicity, but a way to negotiate acculturation while reconstructing a more resistant multi-dimensional identity.23

This brings us to the aforementioned second phase of the formation of Enwonwu’s cultural identity. It is clear that he not only rejects and differentiates the identity that was constructed for him under colonialism, but defines it as an identity in politics. Enwonwu’s alignment with the philosophy of Négritude, his embrace of revived pan-Africanism and his friendship with Senghor, one of the future West African heads of state, indicate that he sought to fight for his liberation.24 While Enwonwu occupied politically relevant positions in government during the transition years to independence and in the new federal state of Nigeria, his positions remained largely symbolic. One could argue that he was offering his undisputed fame to serve as a signifier for a decolonised cultural identity and a symbolic presence for sovereign national pride. His writing and work, however, represent a far more personal struggle, one that could be said to reflect a collective Nigerian strife and a nationally specific response to constructed identities during colonial rule.

Modernism and nationalism

Nigerian modern art and the Nigerian avant-garde are discussed in constant reference to Nigerian nationalism. The year of Nigerian political independence is currently the fixed point for the beginning of decolonisation theories and the beginning of modernism respectively. In 2015, art historian Chika Okeke-Agulu, in recourse to critic Geeta Kapur’s observations on the ties between Indian modernism and nationalism, dates postcolonial modernism in Nigeria around independence.25 He contextualises the decolonising process in relation to national sovereignty and positions postcolonial modernism as avant-garde, which serves to situate the discourse on Nigerian modern art and literature around 1960. However, while this argument is helpful, scholarship has to contend with diverging historical witness accounts, local archives and incomplete international collection records, a complex political and economic interaction between Nigerian sovereignty, the Biafra secession, British sovereign interests, a history of contact with European and American positions as well as pan-Africanism and African Marxist discourse.26 The existence of a modernist artistic practice before postcolonial modernism is implied in the literature, but it is only outlined in one monographic title by Sylvester Ogbechie from 2008, which calls Enwonwu a modernist.27 However, Ogbechie’s definition relies on the frustrating context of a universalist international modernism and positions Enwonwu as an exception. ‘Real’ avant-garde is generally exemplified by ‘natural synthesis’, a theory and manifesto elaborated by artist Uche Okeke in 1959 for his presidential address of the Zaria Art Society, a self-determined artist’s collective and modernist movement:

In our difficult work of building a truly Modern African art to be cherished and appreciated for its own sake – not only for functional values – we are inspired by the struggle of such modern Mexican artists as Orozco and his compatriots. We must fight to free ourselves from mirroring foreign culture … We must have our own school of art independent of European and Oriental Schools, but drawing as much as possible from what we consider in our judgement to be the cream of these influences, and wedding them to our native art culture.28

Fig.9

Uche Okeke

Untitled undated

Ulli Beier Collection, Iwalewahaus

© Courtesy the Asele Institute, Nimo

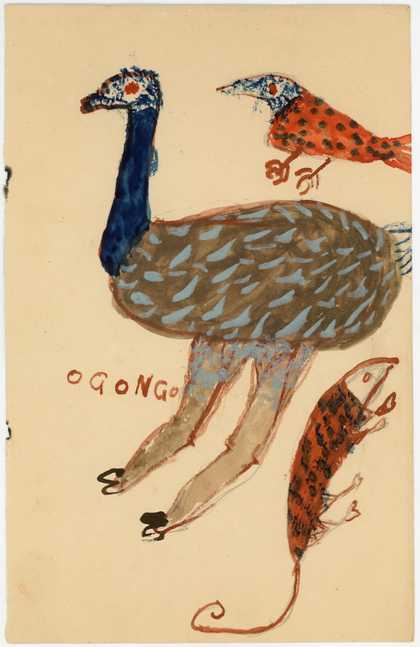

Fig.10

‘Patient T’ (Titus)

Ogongo, illustration from ‘Two Yoruba Painters’, Black Orpheus, no.1, September 1957

Ulli Beier Collection, Iwalewahaus

Courtesy the Ulli Beier Collection

The parameters of Okeke’s theory of natural synthesis and the definition of postcolonial modernism half a century later remain in line with a Western, teleological modernity, art for art’s sake, and an emphasis on individuality and counter-culture. In this respect, independent Nigerian modernism equates to the embrace of abstraction and the progressive hybridisation of ‘native’ Nigerian culture (in the case of Okeke’s own practice, the Igbo tradition of uli art) with selected European and East Asian influences (fig.9).29 Natural synthesis proposes a clean break from colonial influence and suggests romantically that it is completely autonomous, which resonates with the hype around a new national identity.30 Furthermore, the surge of confidence fuelled by nationalism resulted in higher prices being achieved for works by African artists in the early 1960s. Although Enwonwu’s criticism holds – that prices for works achieved by African artists were significantly less than those of their European contemporaries – the rise signified hope.31 The Zaria Art Society was swept up in the excitement of Nigerian independence and nation-building while the influential European commentator Ulli Beier confirmed the prominence of a new Nigerian modernism in his magazine Black Orpheus, which was circulated internationally. In 1961 Beier co-founded the Mbari Club in Ibadan along with South African writer and artist Ezekiel Mphalele and Nigerian poet and playwright Wole Soyinka. Designed at first as an informal gathering place for creatives and the surrounding community, it later became a more formal elite club. The associated independent Oshogbo School co-initiated by Beier and Susanne Wenger, favoured anti-educational and automatic quotations of tribal iconography, outsiderism and surrealism (fig.10). With Beier as the European spokesperson and the ‘credible’ contact for Western collectors and publications, a latent racism took hold, although it is barely detectable as it rests within gestures of sincere, albeit ‘naive’ admiration.

Beier’s passion for outsiderism was inspired by Jean Dubuffet’s art brut manifesto from 1947, which expressly sympathises with works made by people ‘who are presumed to be mentally ill and who are incarcerated in psychiatric institutions’.32 In the transcript of a short speech dated around 1950, the surrealist Andre Bréton refers to Dubuffet’s manifesto and to Joseph-Marie Lo Duca’s essay ‘The Arts and the Lunatic’, writing:

In a world, that is stifled by megalomania and pride, phantasists and the insincere, the term ‘madness’ is relatively vague … authentic madness exists in admirable forms, never hemmed in or paralysed by ‘reasonable’ intent. This is the path to the light of absolute freedom. And it is absolute freedom that gives art a greatness, we only find among the primitives.33

It is quite likely that Beier, who as a German Jew fled the megalomania of the Third Reich, genuinely wished to immerse himself in the perceived ‘absolute freedom’ of the indigenous African spirit. It seems that he saw both the African elite and the wider community through the eyes of a liberal Western intellectual, but nonetheless maintained the idea of the African as ‘primitive’. Beier found himself in the position of the forced émigré, and responded to it by enacting an exotic doubling.34 He was also a keen ethnographer and ‘went native’ without acknowledging his white privilege, which raises questions about Beier’s liminality. For his African collaborators and indeed many African artists, Beier’s status secured interest from the world press in their work. He also acted as a collector himself and encouraged other collectors. The instant recognition that Mbari Club and Oshogbo artists received through Beier’s friendly affiliation seemed to confirm to them that the newfound independence actually worked. To this day the majority of artists and writers in Beier’s wider circle enjoy major international recognition. But Beier’s position did not eliminate racism’s latency in the postcolonial debate. The conceptual quality of the works and their content had little to do with Beier, and yet his name is still indelibly linked with Nigerian art history. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, despite more progressive and inclusive worldviews taking seed, it would have never been possible for an African to command such wide international coverage in such a short time without white private or institutional patronage. Beier’s instrumental co-founder Mphalele wrote:

Mbari’s first year has been a whirlwind of activity. I was privileged to be one of the founders of this club in Ibadan, together with Wole Soyinka (playwright), John Pepper Clark (poet), Mrs Frances Ademola (Ghanaian broadcaster now married to a Nigerian) and Ulli Beier … We decided that it was time that Ibadan, the largest all-African city in the continent, had a centre where people would come and watch an art exhibition, listen to music, see an open-air drama performance and used an African reference library. So we asked the Congress for Cultural Freedom to help us lease part of a building. Promptly this was done.35

During the years just after independence the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), which was a covert subsidiary of the CIA, began to sponsor selected cultural organisations across Africa including the premises for the Mbari Club in Ibadan and Beier’s magazine Black Orpheus.36 The CCF’s wider aim was to introduce Keynesian capitalism linked to ‘freedom’ and ‘independence’ aided by British-American organisations and to prevent socialist ideologies from taking hold after independence. These had indeed come to prominence during the Cold War in Nyrere’s Tanzania, which later recognised the state of Biafra in its short existence, Senghor’s Senegal, Nkrumah’s Ghana and Touré’s Guinea. The CCF-associated Fairfield Foundation, which actually transferred the CCF funds, was headed by another Western authority on African art, Dennis Duerden, who, along with Beier, assumes a permanent presence in books on African history.37 Beier’s and Duerden’s findings remain important archives of their time, but they are just that, limited by their universalist views. They do not exist in exceptional isolation. Ben Enwonwu’s recorded opinions prove beyond doubt that ardent African criticism of these cultural positions existed concurrently.38 As he stated to his peers in Paris:

I am not saying that the European authority whoever he may be, is not sometimes kind enough to offer a commission to an African artist, but the fact is that the African artist must be humble enough to apply for, or receive from the benevolent European something that belongs to the African. The emotional strife involved under such conditions can be a hindrance to free creative energy being directed into its right channel.39

The ensuing fight for influence over the younger generation of Nigerian post-independence modernists between Enwonwu and his peers, expatriate influencers such as Beier, the British Council, the CCF and artist societies themselves divided the African artistic community. The foundations of this struggle cannot be ascertained by what is expressed by any of the influencing parties without considering the cultural bias and the respective international interests of the time.

The paradox of independence

The singular focus on the Zaria Art School in histories of Nigerian modernism circumvents the paradoxes of Nigerian experimentation in contact with Western modernity. This approach sidesteps the agency of Nigerians at different stages of this contact and omits the contextual realities of colonial meddling. Zaria, now named Ahmadu Bello University, is located in Nigeria’s north, a region that was part of the former British Northern Nigerian Protectorate, favoured by the British for the relative ease of introducing Lugardian indirect rule with regional Muslim leaders.40 In 1955 the school partnered with the Slade School of Art and Goldsmith’s College in London. Zaria was small and had European staff, with the exception of the early modernist Clara Ugbodaga-Ngu, who had graduated in London. Even though the Zaria Art School uncoupled itself from London in 1960, the process towards autonomy was undertaken in line with the Ashby Commission Report from 1959, which set out parameters for educational reform in Nigeria with a long-term plan.41 This plan, which was part of the colonial roadmap towards independence, also included the foundation of an autonomous university in Nsukka under the leadership of Nnamdi Azikiwe. Here we can see how the hegemonic ‘support’, both by Britain and the US, during the transition years effectively diffused regional Nigerian agency by supporting an aligned modernism. Due to the difficulty of identifying cross-cultural contact during colonialism, it remains undisputed that Nigerian artist societies such as those in Zaria and Nsukka declared their autonomy of their own accord to promote themselves as cultural agents of the newly independent Nigerian nation.

The claim of a ‘new’ neutrality after independence is one example of what philosopher Santiago Castro-Gómez has described as the ‘hubris of the zero point’, which in this respect functions as the beginning the decolonisation process.42 The idea that legal and institutional autonomy is a prerequisite for decolonisation led to 1960 being understood as the only possible zero point. Yet the pan-African social movement, which began in London in 1897, and the cultural philosophy of Négritude, which developed in the 1930s in Paris, are two known alternatives to this reading.

It is important to point out that the gradual erosion of grassroots pan-Africanism was a direct result of sovereignty.43 After the Second World War the West and the East promoted the idea of a three-world system, and designated Africa ‘third world’ status. This was countered swiftly by a gathering of newly independent countries, which included four African states, to establish intercontinental cooperation between nations supporting ‘non-alignment’ in the Cold War.44 The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was formally established in 1961 in Belgrade and continues to exist today. Nigeria has been a NAM member since 1964. Ben Enwonwu, as a cultural pan-African, carried suspicions vis-à-vis aligned policies, which would partially explain his ferocious opposition to Ulli Beier, the Nigerian artists grouped around him, and the apolitical path they charted.45 In his 1956 speech in Paris he declared that ‘every true artist is bound by the nature of the traditional artistic state of his country, to express, even unconsciously, the political aspirations of his time. And for expressions to be true, they must be an embodiment of the struggle of self-preservation’.46

Enwonwu’s legacy

Pinning Nigerian modernism to the years around 1960 establishes it as emblematic of political and economic change, but also implies that a ‘delay’ took place in West Africa in that the beginning of European modernism is, by contrast, typically dated a century earlier. It seems impossible not to read a hierarchy into this temporal shift. By pointing out the incidental logic of a ‘before’ and ‘after’, of a ‘delay’ or indeed of an ‘absence’, I am merely directing attention to the vestige of hegemonic thinking which is at the root of decolonisation thinking.

It is useful to return to the example of Enwonwu, who reached the height of his fame during the late 1940s and early 1950s after a phenomenal rise to international stardom. His enduring significance as an artist and cultural agitator serves to illustrate the dialectics of individual agency and modernity during the emergence of Nigerian modernism. Enwonwu’s encounter with and sometimes active presence in many of the civil platforms of black intellectual resistance when exhibiting in Paris, London, New York and Nashville in the years 1950–7 suggests an uncolonised mind.47 In addition, original source material, such as his unpublished manuscript ‘Omenka’ and published historical resources, attest to the political significance of his artistic practice.

Enwonwu’s position as one Nigeria’s most famous artists and his centrality to the history of Nigerian modernism was placed in the international spotlight during the centenary of his birth in 2017. In particular, two events in Western institutions reflected a renewed interest in Enwonwu. The first was the symposium ‘Positioning Nigerian Modernism’ at Tate Modern, London, which took place in September 2017, and reflected the expansion of scholarship in the field of Nigerian art history and the gradual establishment of decolonial discourses in Western museums. The second ‘event’ was the jump in bidding results in 2017–18 for landmark works by Enwonwu at London auction houses – the result of increasing interest in the African market, which had been building from 2014 onwards.48 Despite these developments, it is imperative not to construe the serendipitous convergence of these events as an outcome of decolonisation. On the contrary, it calls for a more searching analysis of twentieth-century Nigerian history and in particular before 1960. One observation from the Tate conference was that the use of the term decolonisation has thrown open more questions than answers. These questions are themselves indicative of the significant epistemological shifts within modernity itself. While the historical debate is open to questioning, the concurrent increase in the market value of modern and contemporary Nigerian and West African artworks relies on a rigid belief in the concept of modernity and by extension coloniality. In 2007 the Nigerian art historian Frank Ugiomoh, while discussing the ‘Crises of Modernity’, wrote: ‘As I approach my task of providing insight into collective organisation in African art practices, and how art may help generate social identity and new culture, and “build a nation”, I find myself locked in the dialectics of colonial and postcolonial indeterminacies typical of our era.’49

Coloniality is an essential byproduct of modernity’s principle of incessant progress. Western cultural modernism reproduces modernity’s inherent mandate for progress and relies on uncontested universalism and historical linearity. This narrative plays a pivotal role in the contemporary auction market. British auction houses are leading the financial trade of Nigerian art as an investment or asset. It involves selling works acquired with a colonial valuation back to the Nigerian market at current free-market valuations, thus achieving a fast multiplication of values, which suggests fast growth. This sales activity only confirms the pervasiveness of coloniality. The valuations and the transfer of works impact on the choices of government-funded cultural institutions via rising indemnity costs as well as having a destabilising effect on the efforts of institutions to decolonise.

In the case of art history as it is practised in academia and museums, modernism in the global periphery has often been represented as a second-hand concept infected with Western progressive energy. This also explains its linear delay. Although multiple modernisms of the global periphery are acknowledged in various institutional art historical approaches, they are largely absolved from complicity in the coloniality/modernity construct.50

A thorough review of modernism in Africa would bring to light the progressive, regional cultural responses of African artists to Western culture and education as well as the concurrent ways in which colonial rule was resisted from the beginning of territorial occupation. The epistemology of resistance – a concept borrowed from critical race theorist José Medina – originates from local, predominantly oral, knowledge bases as well as ethno-tribal and socio-cultural constellations.51 In the case of Nigerian art history, we can and should examine art made before and after independence to identify instances of decolonisation. Artists did not operate in a political vacuum. Many instances of civil disobedience mobilised major political change in Nigeria in a relatively short time.

Fig.11

Re-enactment of the 1929 Aba Women’s Riot, Ikot Abasi, 16 December 1989

Some significant revolts include the Aba Women’s Riot of 1929, which challenged exploitative taxation (fig.11). The riot surfaced the disruptive power of labour struggles, which undermined not only colonial authority, but importantly its unilateral economic efficacy. When the effect of the Second World War trickled down into the Nigerian economy, the General Strike in Nigeria in 1945 brought the trade unions together, while the Egba women’s tax revolt in 1947 represented another significant push by Nigerians against colonial autocratic rule during the early years of the Cold War. Between 1945 and 1948 a spate of unsolved ‘spirit’ killings in south-eastern Nigeria revealed insurmountable conflicts between local rule and imperial rule and the influence of local spiritual societies on the nationalist struggle.52 The intellectual struggle is exemplified by the wide circulation of the independent newspaper West African Pilot, which was funded entirely by its readership.53 Under the leadership of Nnamdi Azikiwe the newspaper published political content, which was pro-nationalist and openly critical of colonial rule.54 The West African Pilot, and particularly Azikiwe, provided a platform for the writings and political cartoons of Akinola Lasekan, and repeatedly published Ben Enwonwu’s texts. The strong connection between Azikiwe as a publisher and the politicised elite, along with the local anti-imperial and labour revolts, speak to the growing shift in power, which gradually turned the anti-imperial national interests into a political reality.55

Recent observations on Nigerian postcoloniality point to the problems of locating the wider impact of colonial legacies. In his paper ‘The Postcolonial State and Ethno-Politics in Nigeria’ Mohammed Sulemana draws upon the work of political commentator Mahmood Mamdani when he writes: ‘To confront contemporary problems with colonial origins it is imperative to configure “the political agency of colonialism”’.56 Without naming the agency of colonialism, it is impossible to define Nigerian agency as an alternative to the hegemonic narrative. Furthermore, it is impossible to articulate what constitutes a Nigerian identity, because its construction begins with the agency of colonialism. The name ‘Nigeria’ was a linguistic construction created by a British trader, William Cole, and a government-approved explorer, William Baikie, around 1859. It was used to describe the area and populace around the River Niger and the river itself as a territorial axis for the mapping of a future colonial state.57 The name ‘Nigeria’ was popularised by journalist Flora Show, the future Lady Lugard, in an article for the Times in 1897. Constructed ethnicities obfuscate real identities to a point where the colonised subject needs to de-link themselves from their own skewed self-perception.

In the case of Ben Enwonwu, we can observe how he de-linked and then reconstructed a new more differentiated identity, at least within the creative language he developed. This reconstructed identity then became the basis for a political struggle, which co-opted him into a social shift – nationalism – that enabled his de-linked identity to function. The first instance occurred at the point of independence. When the legacy of colonialism turned out to be more far reaching and facilitated new constructed identities in the ‘free’ option of coloniality, the cultural identity reconstruction in Enwonwu’s case failed. His own legacy became contested, his status as a signifier – the national cultural icon – became unstable, at times invisible, even absent. The recent ‘reappearance’ of Enwonwu’s legacy coincides with the epistemic crisis of Western modernity itself. In fanning out the terminology we have the tools to depart from our own implication in the politics of our time. What we know now of the different geopolitical locations of modernism, including Nigeria, allows us to reassess our terms of enquiry.