When Ben Enwonwu had his first American solo show at Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. in 1950, the William E. Harmon Foundation, as the organiser of the subsequent tour, began searching for adequate venues to exhibit the Nigerian modernist’s work. As art historian Sylvester Okwunodu Ogbechie notes in his monograph about Enwonwu, finding established galleries in the US for exhibiting contemporary art from Africa was not an easy task for the foundation.1 It was against the backdrop of the racially segregated art world of the early 1950s that the Illinois-born African American painter Hale Woodruff produced his pictorial account of the arts of the world in his six-mural cycle The Art of the Negro.

Woodruff worked on The Art of the Negro for the Trevor Arnett Library at Atlanta University in Atlanta, Georgia between 1950 and 1951, where it appears on canvases mounted in six arched niches above the library’s card catalogue.2 With this project he aimed to depict the genealogy of modern art in the wider context of the history of mankind, colonial power and the policies for emancipation from slavery and colonial oppression. Although the cycle is titled The Art of the Negro, it encompasses more than just a painted history of African and African American art, offering a vision of world art from the point of view of an African American painter in the mid-twentieth century. Executed for one of America’s most prominent black universities,3 Woodruff’s mural cycle is not limited to the cultural axis of the ‘Black Atlantic’, as historian Paul Gilroy defined the transatlantic space of black history and culture made up initially by the slave trade;4 the cycle also incorporates the arts and cultures of Europe, Central and South America, and the Pacific in its panorama of violent and culturally fertile encounters in the colonial contact zones.

The Art of the Negro can be understood as an early attempt to represent the history of art from a transcultural perspective: one that emphasises cultural contact and processes of exchange and translation.5 Long before the attempts made by twenty-first-century scholars to compile a global art history,6 Woodruff’s work brought this broader scope to the debate about post-Eurocentric art history writing, and did so from an artist’s point of view. As this article will show, the mural cycle reveals a black artist’s perspective on contemporary American debates about the genealogy of modernism, and can illuminate the position of African and African American modernism in the context of mid-twentieth-century institutional politics and art history writing in the West.

Black history and genealogies of modernism

The decade before Woodruff began working on the Atlanta murals saw the rise of the New York School of abstract expressionist painting, which came to be characterised as the first genuinely American modern art movement. Painters such as Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko, and critics like Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, were busy elaborating on what was distinctive about ‘American-type painting’, as Greenberg would come to refer to the paintings of Newman, Rothko, Arshile Gorky, Adolph Gottlieb, Jackson Pollock and others.7 These artists and critics regarded the abstract paintings of the New York School – with their flat planes of colour, lack of discernible subject matter and emphasis on form and medium rather than representation or depth – as the universal art of the time and an expression of the tragic condition of modern man.8 The enterprise of bringing forth an American brand of modernism that was also universal was predicated not only on a specific interpretation of modern European art – one that stressed its linear progress towards greater abstraction and truth to the medium – but also on the influence of myth and ritual both in European antiquity and in Native American art. Of special relevance here is the appropriation of Native American art by the abstract expressionists, in which they took up what they regarded to be features of indigenous arts without concerning themselves with the historical experience or social status of the groups that produced them. Writing about contemporary art’s relation to Mexican and Native American art, Newman stated: ‘To be close to one’s country one must be close to its art rather than to the contemporary people who surround one’.9 Mid-century white American modernism thus claimed a transhistorical affinity with the artistic expression of other cultures, while also rejecting any form of regional, social or ethnic specificity in the production of art.

It was necessary for African American artists of this era to come to terms in one way or another with the universalism of white American modernism. The art world of the 1940s was, like American society as a whole, marked by racial segregation. With few exceptions, black artists showed their work mainly in exhibitions devoted to ‘negro artists’ that were mounted by specific organisations and funded by special foundations.10 In addition to the institutional racism of the art system, which tried to relegate black artists to the places assigned to them, these artists were also confronted with an artistic problem: how to reconcile the black experience in a racist society with the dogma of abstraction and the purely formal focus of the avant-garde. How could the emphasis on formalism in art be taken seriously by a politically oppressed and socially marginalised group, and turned to productive use? Ever since the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s many African American artists had dedicated their talents to evoking the black experience, both to support the struggles of their own people and to show the general public the cultural achievements of the oppressed group. How could these artists, now facing new parameters for what was considered artistically progressive, continue to imbue their art with this socially critical and emancipatory function? Hale Woodruff seemed to address these questions when planning and executing his cycle The Art of the Negro.

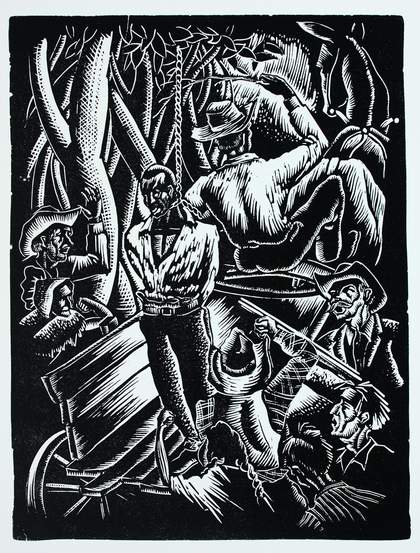

Fig.1

Hale Woodruff

Giddap 1935

High Museum of Art, Atlanta

© Estate of Hale Woodruff/VAGA, NY

During the 1930s, which he spent mostly as an art teacher at Atlanta University, Woodruff worked in a social realist style in order to either convey the adversities faced by African Americans or to create an empowering image of historical black struggles. The former type of work is exemplified by two linocuts from Woodruff’s Atlanta period, Giddap 1935 (fig.1) and By Parties Unknown 1935 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), which address with explicit imagery the ‘white terror’ perpetrated in the segregated South, and the brutal practice of lynching in particular. The second group of works is best represented by his murals for Talladega College in Alabama, executed from 1938 to 1939. They marked the hundredth anniversary of the revolt of the Mende slaves on the Spanish ship Amistad and were designed to instruct black students about their ancestors’ struggle for liberation (see, for instance, The Mutiny on the Amistad 1939; fig.2).11 In this cycle, painted in a monumental and energetic figural style, Woodruff was able to translate his experiences as assistant to muralist Diego Rivera in Mexico two years earlier into his own portrayal of a revolutionary moment in black history. During his six-week stay in Mexico, Woodruff had assisted Rivera in the execution of murals for the Hotel Reforma in Mexico City. He reflected in 1968 that: ‘My going to Mexico was really inspired by an effort to get into the mural painting swing. I wanted to paint great significant murals in fresco and I went down there to work with Rivera to learn his technique.’12

Fig.2

Hale Woodruff

The Mutiny on the Amistad 1939

Talladega College, Alabama

© Estate of Hale Woodruff/VAGA, NY

Fig.3

Hale Woodruff

Afro Emblems 1950

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

© Estate of Hale Woodruff/VAGA, NY

In the 1940s Woodruff moved relatively freely between the white and black art scenes in New York. He met with New York School artists and in 1946 was one of the first African American art teachers to be hired by New York University, where he mostly taught white art students. During these years immediately preceding his work on the Atlanta University murals, Woodruff’s painting style was very close to that of some of the better-known abstract expressionists, in particular Adolph Gottlieb. His abstract works, however, often included allusions to black culture, as is made plain in the title and forms of the painting Afro Emblems 1950 (fig.3). Woodruff identified with the main concerns of the New York School, including the search for what is universal in art, but with one important difference: instead of taking pains to avoid any specific cultural references like his white colleagues had, Woodruff expanded what could be understood as ‘universal’ by highlighting the universality of African art. In a 1968 interview he formulated in precise terms his understanding of the universal in art, which for him always depended on location and situation:

I think all art if it’s worth its salt has got to be universal. But it comes from a local source, you see. That’s it. It can be as local as all get-out, but it has to have this transcendental quality in order for it to be universal. Now it can be black art; it can be yellow art; white art; anything. But it comes from a local source.13

With this universalism based on difference, Woodruff’s reasoning is similar to concepts put forward by thinkers like Aimé Césaire, whose ‘idea of the universal is that of a universal rich with all that is particular, rich with all particulars, the deepening and coexistence of all particulars’.14 Woodruff stated further:

You see, any black artist who claims that he is creating black art must begin with some black image. The black image can be the environment, it can be the problems that one faces, it can be the look on a man’s face. It can be anything. It’s got to have this kind of pin-pointed point of departure. But if it’s worth its while, it’s also got to be universal in its broader impact and its presence.15

Woodruff’s lifelong interest in the art of Africa was sparked in the early 1920s, when the German artist Hermann Lieber gave him the 1921 book Afrikanische Plastik (African Sculpture) by Carl Einstein.16 His engagement then deepened further in conversations with the philosopher Alain Locke, the most influential promoter in the days of the Harlem Renaissance of black artists studying the art of their African ancestors.17 It was also enhanced during a four-year stay in Paris in the late 1920s, when Woodruff began to collect African art. In a later interview from around 1972, Woodruff recalled his first encounter with African art through Einstein’s book:

I had never heard of the significance of the impact of African art. Yet here it was! And all written up in German, a language I didn’t understand! Yet published with beautiful photographs and treated with great seriousness and respect! Plainly, sculptures of black people, my people, they were considered very beautiful by these German art experts! The whole idea that this could be so was like an explosion. It was a real turning point for me. I was just astonished by this enormous discovery.18

Before his relocation to New York in the 1940s, Woodruff had organised numerous exhibitions of African and Mexican art as well as contemporary art. By the time he began work on the murals for the library in Atlanta in the 1950s, he had further deepened his knowledge of African, European and American art and had found his own way to meld abstraction and Africanism in his painting.19

Although the programme Woodruff chose for the Atlanta murals is unique in taking the history of art as its focus, The Art of the Negro can undoubtedly be seen in the context of the then still young tradition of African American artists creating mural paintings for black educational institutions. Also exemplary of this new form of black history painting is Aaron Douglas’s 1930 mural scheme for a series of rooms at the Fisk University Library in Nashville, Tennessee. Here Douglas depicted black history spanning the African past to the enslavement of Africans and their subsequent emancipation, as well as the achievements of his people in the arts and sciences. His artistic work thus corresponded to an important historiographic project of the time, which the African American historian Arthur Schomburg described in the mid-1920s as ‘The Negro Digs Up His Past’ in an essay of the same name. The aim was to point to the need to rewrite black history, which had been misrepresented during centuries of colonialism and slavery by the predominant white culture.20

Woodruff had first proposed the execution of a mural for the Trevor Arnett Library to Rufus E. Clement, Atlanta University’s president, in 1938, but his submission was not accepted. If the artist had been commissioned to paint the mural cycle at that time, its subject matter would likely have been more in line with that of other African American mural paintings of the 1930s and 1940s, which depicted black history and education. Woodruff explained that he changed to representing black art history in the cycle because he ‘wanted it to be something of an inspiration to the students who go to that library, to see something about the art of their ancestors’.21 Despite its singular concept, Woodruff’s cycle in Atlanta was part of the push to write about black history in new ways, in this case with a focus on black art. Before turning to analyse the mural paintings in more detail, there is another form of contemporary history writing to consider, one that directly relates to the history of art and the position of the black artist within it.

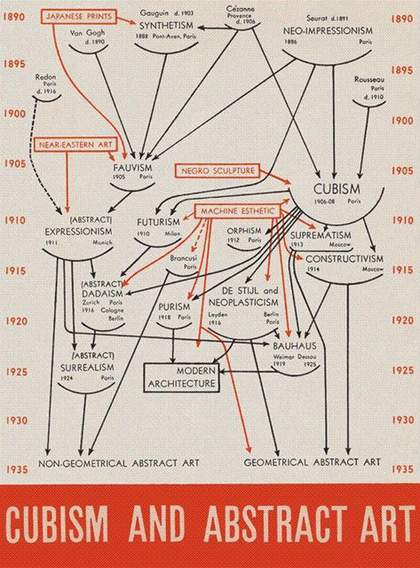

Fig.4

Alfred H. Barr

Cover of Cubism and Abstract Art, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1936

During the 1930s and 1940s, art and art history in the US were preoccupied with the question of the genealogy of modernism. In his famous diagram that was featured on the cover of the catalogue for the exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1936 (fig.4), curator Alfred H. Barr delineated a schematic, exclusively European history of modern art movements, from post-impressionism to the art of his day. Barr’s genealogical chart presents a clear separation between artistic movements, which are shown in black, and non-artistic influences, shown in red. Very telling for his understanding of non-European art is the fact that he put ‘Japanese Prints’ and ‘Negro Sculpture’ in the non-artistic category with ‘Machine Esthetic’.

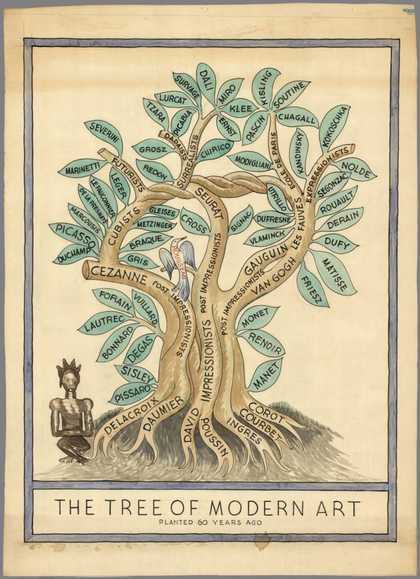

Fig.5

Miguel Covarrubias

The Tree of Modern Art, Planted 60 Years Ago 1940

David Rumsey Map Collection, Stanford University, Stanford

© Estate of Miguel Covarrubias

The 1933 illustration The Tree of Modern Art, created for Vanity Fair’s art print portfolio by the New York-based Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias, shows only the names of white artists, from French Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) to Spanish painter Joan Miró (1893–1983). These are marked on the roots, branches and leaves of the tree, while an African sculpture in the lower left corner of the composition is depicted more in the position of a spectator than a source.22 A classical marble head is seen next to the African statuette and, on the other side of the tree trunk, an art lover is shown holding a gold frame. A later version, the 1940 The Tree of Modern Art, Planted 60 Years Ago (fig.5), depicts only the African sculpture in an observer’s stance. The way Covarrubias positions African art in relation to modern European art in both versions brings to mind Pablo Picasso’s statement in 1923 that the African artworks he kept in his studio were more witnesses to his development of cubism than influences on it.23

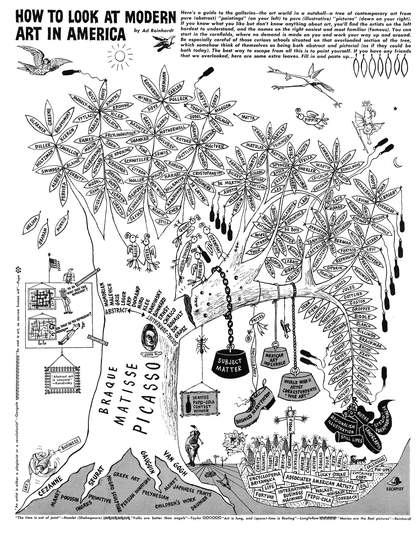

Fig.6

Ad Reinhardt, ‘How to Look at Modern Art in America’, PM, 2 June 1946, p.13

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2018

A more complex political and semi-ironic response to the need for a genealogy of American modernism is Ad Reinhardt’s famous drawing How to Look at Modern Art in America (fig.6), which was published in 1946 in the magazine PM.24 Reinhardt included some Latin American artists like Matta and Wifredo Lam, and African American artists such as Norman Lewis and Romare Bearden, in his representation of the tree of contemporary art. Since Woodruff moved for a time in the same New York artist circles as Reinhardt, it is possible that he was familiar with this type of historiography of art in the form of charts and genealogical trees. Even if the history of ‘negro art’ was Woodruff’s main concern, the murals in Atlanta can nonetheless also be understood as his response to this graphic way of telling art history. Yet considering Woodruff’s cycle from the perspective of a global art history, it differs from the above-mentioned genealogies in one essential way. Whereas Barr, Covarrubias and Reinhardt all speak of modern art in general but present its history as a white European one, Woodruff speaks of ‘negro art’ specifically and places its history in the context of its manifold connections with the art of other peoples and regions.

Black art in a global context

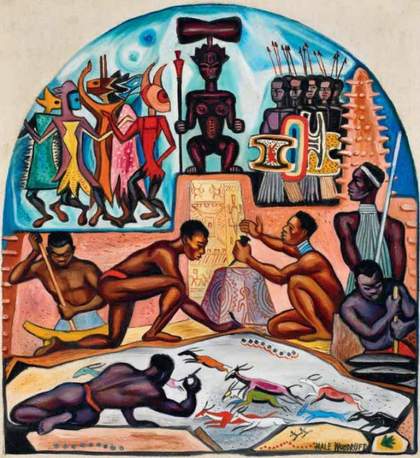

Fig.7

Hale Woodruff

Native Forms 1950–1, panel 1 of The Art of the Negro

Oil on canvas

3660 x 3660 mm

Clark Atlanta University Art Collection, Atlanta

© Estate of Hale Woodruff/VAGA, NY

Photo: Christian Kravagna

Fig.8

Hale Woodruff

Interchange 1950–1, panel 2 of The Art of the Negro

Oil on canvas

3660 x 3660 mm

Clark Atlanta University Art Collection, Atlanta

© Estate of Hale Woodruff/VAGA, NY

Photo: Christian Kravagna

Let us now turn to the style and content of the six panels in the cycle The Art of the Negro. Panel 1 is titled Native Forms and presents the African origins of black art in rock paintings, masks, sculpture and dance (fig.7). The scene shows African painters and woodcarvers at work under the supervision of a central figure representing the Yoruba deity Shango, along with groups of people carrying out performances, such that art appears to be part of people’s daily lives. Panel 2, titled Interchange, deals with contact, communication and cultural exchange between the ancient civilisations of Africa, Egypt, the Middle East and Greece (fig.8). Small groups of representatives from different cultures congregate in an allegorical setting which, with its plethora of antique artworks of varied origin, is reminiscent of a museum. People are depicted listening to one another and to a musical instrument at the left of the composition, conversing at the right, and carrying out scientific calculations in the foreground.25

Fig.9

Hale Woodruff

Dissipation 1950–1, panel 3 of The Art of the Negro

Oil on canvas

3660 x 3660 mm

Clark Atlanta University Art Collection, Atlanta

© Estate of Hale Woodruff/VAGA, NY

Photo: Christian Kravagna

Fig.10

Hale Woodruff

Parallels 1950–1, panel 4 of The Art of the Negro

Oil on canvas

3660 x 3660 mm

Clark Atlanta University Art Collection, Atlanta

© Estate of Hale Woodruff/VAGA, NY

Photo: Christian Kravagna

Following this harmonious depiction of intercultural exchange in ancient times, panel 3, bearing the title Dissipation (fig.9), illustrates a drastic rupture in the history of black art. It portrays the violent invasion of the colonial powers and the resulting destruction and plundering of the artworks of various African cultures, for example Benin bronzes, Songue masks and the architecture of the West African Songhai people. In panel 4, Parallels (fig.10), Woodruff then resumes with another approach to representing the arts of the world. In contrast to panels 1–3, the artworks are no longer embedded in the life of the societies producing them. Rather, they are shown isolated, each in a separate field of colour, divided by painted lines from their neighbours from other cultures. Here Woodruff includes objects not usually associated with the history of black art, namely Aztec and Polynesian art and totem poles from the Native American culture of the Pacific Northwest, which were for the New York School of painters a favoured reference point for their notions of myth, horror and ritual.26 Parallels does not display any spatial or narrative coherence, as is the case to varying degrees in the first three panels. Without a sense of pictorial space or depth, the paintings and sculptures from all over the world are seen side by side, not unlike a museum presentation.

Fig.11

Hale Woodruff

Influences 1950–1, panel 5 of The Art of the Negro

Oil on canvas

3660 x 3660 mm

Clark Atlanta University Art Collection, Atlanta

© Estate of Hale Woodruff/VAGA, NY

Photo: Christian Kravagna

Fig.12

Hale Woodruff

Influences 1950–1 (detail)

Panel 5, titled Influences (fig.11), echoes the composition of the previous mural, placing the depicted artworks in separate fields. The theme of this panel is the influence of non-Western art on modernism. It features the characteristic styles of artists such as Amedeo Modigliani in the centre, Joan Miró on the left, Henry Moore at the bottom and possibly Paul Klee at the upper right. In addition to these masters of European modernism, we also see here Haitian Vévé ground drawings (on the left above the Henry Moore) and African sculpture (on the right). Along with the white modernists and the representatives of non-European sources of influence, pride of place is also given to the African-Cuban painter Wifredo Lam (centre right; fig.12). At this time Lam was the youngest artist of all those in the panel, as well as the least well known in the US. Lam is now considered to be one of the first artists to subject European primitivism to a black reappropriation. Primitivism was the practice of Western artists borrowing aesthetic elements from the so-called ‘primitive’ cultures of the colonised world and incorporating them into their modernist visual experimentation. As the art historian Lowery Stokes Sims has noted, ‘Lam’s adaptations of European modernist styles already informed by African (as well as Pacific and Amerindian) elements engage notions of originality and authenticity’.27 Lam’s Afro-Cuban recontextualisation of primitivist elements of modernist art was part of an explicit decolonising agenda in his work. He regarded himself as ‘a Trojan horse that would spew forth hallucinating figures with the power to surprise, to disturb the dreams of the exploiters’.28

With the prominent position accorded to Lam, this panel illustrating black influences on white modernism takes a striking turn in the direction of a network of global modernisms. Lam was arguably the transcultural artist par excellence, one who travelled back and forth between the art worlds of France, the Caribbean and New York and maintained close contacts with Picasso, the surrealists, Césaire in Martinique, and the Cuban and Mexican art scenes.29 In this mural, Woodruff’s decision to position Lam’s amalgamation of cultural and aesthetic influences, based on Cuban Santéria and Haitian voodoo, beside the Haitian Vévé drawings is especially significant. Woodruff chose for his reference to Lam a motif central to Lam’s painting, namely the Santéria deity called Elegguá, a trickster figure and messenger who connects earthly life with the supernatural world. In Haitian voodoo the crossroads is also a central symbol – as indicated here by the Vévé drawing – which makes contact with higher beings possible. The prominent placement given to Lam’s transculturalism in this composition, along with the other symbols of contact and communication between different worlds, marks Woodruff’s work as a powerful commentary on art and cultures in motion.30

Fig.13

Hale Woodruff

Muses 1950–1, panel 6 of The Art of the Negro

Oil on canvas

3660 x 3660 mm

Clark Atlanta University Art Collection, Atlanta

© Estate of Hale Woodruff/VAGA, NY

Photo: Christian Kravagna

More conventional, both in style and subject matter, is panel 6, titled Muses (fig.13). Here the artist concludes the cycle with a figurative, allegorical depiction of a community of black artists. Under the watchful eye of both Greek antiquity and African tradition – each represented as sculptures – is assembled a group of black artists from across the ages from Africa, Europe, Latin America and North America. Among them are contemporaries and friends of Woodruff, such as Jacob Lawrence and Charles Alston, but also historical figures including, from the seventeenth-century, Juan de Pareja, assistant to Diego Velázquez, and Sebastián Gómez, a pupil of Esteban Murillo. Also depicted are the African-Brazilian sculptor and architect Antonio Francisco Lisboa (1730–1814), known as Aleijadinho, and an ancient African rock painter. As their attributes show, they all work in different styles but maintain contact and dialogue with each other. This panel can possibly be understood as Woodruff’s answer to The Club, the name given to the group of abstract expressionists of the New York scene, which Woodruff would have known from his New York years.31 It is also reminiscent of famous photographic group portraits of the New York School, such as the one by Nina Leen captioned ‘Irascible Group of Advanced Artists Led Fight Against Show’, which appeared in Life magazine in January 1951.32

In its references to the diversity of artistic modes of expression, Muses also seems to reflect Woodruff’s own movement between different styles. Art historian Ann Eden Gibson remarked on ‘Woodruff’s alternation between abstraction and more mimetic representation from painting to painting’, noting that ‘he saw abstraction, expressionism, and realism as codes, as tools, rather than values in themselves’.33 Furthermore, the prominent place given to Lam’s transculturalism in panel 5, along with the other symbols of contact and communication between different worlds, marks Woodruff’s work as a powerful commentary on art and cultures in motion. His entire cycle revolves around the subject of the historical and current connection or fusion of forms, ideas and motifs from various cultural sources. This dynamic cultural model based on the overcoming of difference is politically significant given the activism against racial segregation that was taking place in the southern states of the US at the time.

Abstraction, universalism and race consciousness

Fig.14

Hale Woodruff

Study for The Art of the Negro: Native Forms 1950

Oil on canvas

578 x 530 mm

Harn Museum of Art, Gainsville

© Estate of Hale Woodruff/VAGA, NY

As is evident from the descriptions of Woodruff’s panels, the artist switched modes of representation from one scene to the next, depending on the subject matter and the statement he wanted to make with each picture. All six panels are dominated by a figurative style, while spatial, temporal and narrative coherence are conceived differently in each, and abstract or symbolic forms have varying degrees of prominence. This variation across the panels may be partly attributed to the length of time between the cycle being proposed, accepted and executed. As mentioned above, Woodruff put forward his proposal in the late 1930s, while teaching in Atlanta and during the execution of his murals for Talladega College in 1938–9. The Atlanta commission was not granted until after he had taken the job at New York University in 1946, and Woodruff first began designing the compositions for the murals on canvases in his New York studio in the mid-1940s. If we compare the designs for the cycle that Woodruff produced at this time, still marked by a rather harsh realism (see, for instance, fig.14), with the final paintings of 1950–1, his stylistic shift within the milieu of abstract expressionism in the late 1940s becomes obvious. As curator Edmund Barry Gaither has noted, Woodruff’s murals for Atlanta University ‘bring together his long interest in African art and his growing association with abstract expressionism’.34 This coalescence is likely the reason for the aesthetic variety evident in The Art of the Negro, but what is the effect of this integration of abstraction and historical narrative? What solution does the artist find to meet the specific need of conveying a message to library users at a black university?

The variety of forms of artistic expression adopted by black artists is one of the themes of the final panel, Muses, which, as outlined above, shows artists in conversation alongside decorative floral and abstract geometric images, as well as figurative sculptures. Woodruff was clearly aware of the problem of style. For an African American painter who identified with the formalist qualities of the abstract expressionists, being commissioned to paint a set of murals for a prestigious black university in the segregated South was a challenge that called for a decision to be made. The library of a university for African American students and professors is not a museum, a collector’s home or a corporate lobby, where the purely aesthetic qualities of abstract art can be appreciated. Here, a story with a message was desired, an iconography that would support the educational mission of the institution. This included raising the racial consciousness of the student body, as was the aim, for example, of Douglas’s mural at Fisk University and Woodruff’s own cycle for Talladega College. Atlanta University perhaps viewed this mission as even more vital, as it was for many years home to writer and activist W.E.B. Du Bois, who endorsed an understanding of art as propaganda for the black cause. Du Bois had also promoted Woodruff’s work when he was a young artist in the 1920s, giving him commissions that included designing the covers of the Crisis, the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.35

Nevertheless, taking recourse to the more conventional realist style of his early years was out of the question for Woodruff. In a statement on the considerations that went into his ideas for the project, the artist began by expressing his high regard for the African art of ‘my ancestors’ and then went on to say:

These murals would deal with a subject about which little was known – art, and also among Negroes, there was little concern about our ancestry. Then I took the idea that art, being a little known subject, would attract the curiosity and attention of young people, as well as older people, toward further study and in that way the murals would have educational value.36

The choice of art history as a theme was unusual for the mission at hand. Instead of telling a general or regional history of African Americans, as the murals at many black institutions had done since the 1930s, Woodruff decided instead to recount the history of black art and its global and transcultural dimensions. He hoped in this way to elicit curiosity and interest in a more in depth engagement with art and cultural heritage, as he maintains in his statement. Furthermore, as unconventional as the theme of art history is in the genre of mural paintings at black universities, it can nonetheless be explained with respect to the activities Woodruff pursued for many years in Atlanta. He was a leading force in the establishment of an art college at the university, while also starting a university art collection. In addition, he organised a series of exhibitions of African and Mexican art at Atlanta, and established an annual Exhibition of Paintings, Prints and Sculpture by Negro Artists of America starting in 1942, usually referred to in short as the Atlanta Annual, which soon became the foremost regular event in this field.37

Painting across the colour line and transcultural art history

With his cycle on the history of black art from its beginnings to the present, Woodruff offered the students, faculty and guests of the university a historical framework for their current exhibitions and art education. But the fact that he chose to focus so heavily on transcultural contacts, influences and exchanges is the most intriguing aspect of this work in terms of its subject matter.38 One of the reasons for this choice may lie in Woodruff’s own stylistic development during his New York years. This was shaped significantly by his experience of interchanges with artist colleagues from various backgrounds and the knowledge he thus gained of non-European influences on white modernist art – in other words, the fusion of Euro-American and African design elements and motifs in works by artists such as Wifredo Lam.

The explicitly transcultural perspective of the Atlanta cycle may also be due to Woodruff’s simultaneous struggle against ethnic segregation in art exhibitions. During the 1940s the artist advocated for a move away from the model established since the Harlem Renaissance of mounting separate exhibitions of the work of ‘negro artists’. This also applied to the annual exhibition he himself had initiated at Atlanta University, which after a few years he tried to open up to all artists, regardless of ethnicity. Woodruff was concerned here not just about the political aspects of separating exhibitions of white and black artists; of special importance to him was creating a productive atmosphere of artistic exchange and reciprocal fertilisation. As for the Atlanta Annual, Woodruff failed at his attempt to present an integrated show due to the resistance of university president Rufus Clement, who argued the opposite view, citing the already limited possibilities for black artists to exhibit.39 Woodruff reflected on this dilemma in an interview in 1968:

In the early Forties we had developed to the point where we put on a national show. We invited artists from all over the country to show at Atlanta University. This was for black artists alone. Incidentally, this exhibit is still held every year in Atlanta. I had some discussion about it with the President of the University in later years. I felt that the black, exclusively black, show had served its purpose by the early Forties and I proposed that they expand the scope and include artists of all races. But this was not approved and it was never done, so even to this day I think it is still a segregated show.40

Art historian Morgan Sumrell has described Woodruff’s deliberations about desegregating exhibitions in words that could also be applied to the tenor of his wall paintings: ‘He wanted to create a somewhat aesthetic conversation between artists of all different calibers, levels, and races in order to expound upon a multitude of styles, ideas, and creative thinking.’41 This motif of the ‘aesthetic conversation’ that reached beyond ethnic and cultural boundaries, which Woodruff was unable to realise with the Atlanta Annual, seems to be presented in panels 2 (Interchange), 5 (Influences) and 6 (Muses) of The Art of the Negro, where it is characterised as an engine for artistic creativity from antiquity to modernism.

Fig.15

Hale Woodruff

Interchange 1950–1 (detail)

Fig.16

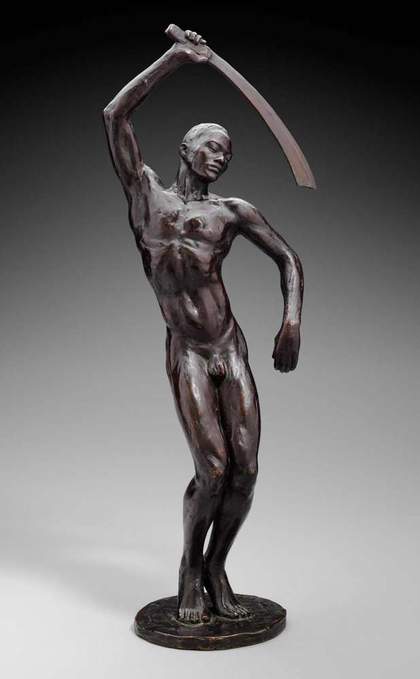

Richmond Barthé

Féral Benga 1935

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

© Barthé Trust

Fig.17

Hale Woodruff

Native Forms 1950–1 (detail)

Woodruff managed to integrate the figurative narrative required by the Atlanta commission into his newer abstract approach using two strategies. One was to subject the human figures, larger objects and in some cases the background to a stylisation of forms and fracturing of surfaces, in keeping with techniques used both in African and modernist art. The figure on the left in Interchange, for example (fig.15), has elongated limbs that suggest a kinship with sculptures by Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881–1919) and Richmond Barthé (see, for instance, Lehmbruck’s Dancer 1913, Museum of Modern Art, New York, and Barthé’s Féral Benga 1935; fig.16). Barthé, an African American sculptor and contemporary of Woodruff, is portrayed in the right foreground of the panel Muses. In Native Forms, the stylisation of the figures and the prismatic fracturing of figures and objects – in a late cubist manner that perhaps recalls most strongly the paintings of Lyonel Feininger – result in a blurring of the distinctions between the individuals depicted and the images created by them.42 The stylised drawing of masks and the geometric shapes that make up the shields carried by the group at the upper right reduce the physicality of the humans portrayed (fig.17), so that the group bears a greater resemblance to the imaginary beings that appear on the opposite side of the panel. The geometric rendering of objects, backgrounds and costumes in panels 1–3 gives the impression of figures fusing with their surroundings.

Fig.18

Hale Woodruff

Native Forms 1950–1 (detail)

Fig.19

Hale Woodruff

Interchange 1950–1 (detail)

Fig.20

Willi Baumeister

Scherzo (Riesen Abschied) 1948

Galerie Schlichtenmaier, Stuttgart

© Willi Baumeister/VG Picture Art, Bonn

Along with this gradual abstraction of the figural elements, the second technique Woodruff used was to highlight abstract or nearly abstract zones in a predominantly representational image. In the first two panels, Native Forms and Interchange, the viewer’s attention is drawn to the artist’s interest in historical styles of painting and writing that can be associated modernist abstraction. This applies, for example, to the scriptural and symbolic zones in both murals (see figs.18 and 19), which recall paintings that Willi Baumeister and Paul Klee developed based on foreign systems of writing, such as Arabic and Egyptian hieroglyphs (see, for example, Baumeister’s Scherzo (Riesen Abschied) 1948; fig.20). With its irregular geometric shapes the blue area on the left above the rock painter in Native Forms is related closely to abstract images Woodruff himself was producing at the time he executed this commission (see, for instance, Afro Emblems, fig.3; and Carnival 1950, private collection). The fact that these more abstract fields are framed, like the works of modern art depicted in panels 5 and 6, makes the shapes within them look like autonomous pictures set among a scenic narrative environment. Woodruff first developed the method of dividing pictures into several smaller fields in some of his abstract paintings on canvas, including Afro Emblems and Carnival.43 Here in the murals, these fields form what curator Mary Schmidt Campbell has described as ‘self-contained zones’44 in the context of a painted history.

In the murals, the interaction of these two artistic approaches – the stylisation and fracturing of figures, and the integration of abstract zones – has the effect of making the picture surface of each panel and the structure of its composition much more visible and present than in Woodruff’s earlier works. It also lends the mostly figurative cycle a quasi-abstract look that supports the part of the narrative that emphasises the importance of African art as a source for modernist abstraction.45 In this way, Woodruff, who did not include himself in the pantheon of black artists shown in panel 6, could manifest himself as an abstract painter operating within a narrative programme. Thus the artist, in the specific context of producing a library cycle, found a solution to the problem of manoeuvring between ‘blackstream’ and mainstream. The task of fusing abstraction and history painting was arguably part of the same problem as the task of reconciling primarily aesthetic issues with the articulation of black experience, with the aim of transcending the boundaries of the largely segregated art worlds. Woodruff’s commitment to this desegregation is reflected artistically in The Art of the Negro in a programme that illustrates the fruitful interchanges between ancient civilisations as well as the influences of African, Oceanic and Pre-Columbian art on modernism, and which also gives a prominent place to a key transcultural artist in the figure of Wifredo Lam.

Woodruff did not, however, pursue any naive notion of transculturalism. He by no means glossed over the dramatic caesura that black art suffered as a result of colonialism. The colonial violence that is vividly portrayed in Dissipation destroyed African art or else wrested these art objects from their social and spiritual contexts. In the background of this panel, African buildings burst into flames, and in the foreground white men are seen smashing or carting away sculptures. In addition to this cultural devastation, the other effect of colonial intervention is the geographic dispersal of artworks and their transformation into museum objects. In this sense, this scene corresponds to the motif of enslavement and shipment of Africans in the more common representations of African and African American history in the murals of the period. But while these usually focus on the origins of the African diaspora by showing the commodification of humans, who are turned into goods to be dispatched across the Atlantic via the ‘Middle Passage’ of the transatlantic slave trade, Woodruff recasts this motif by showing how culturally meaningful works of art that once had a social function are transformed into objects that inspire greed and trade, finally ending up tucked away in museums. The Benin bronzes to the left of the centre in Dissipation are a clear reference to the so-called ‘punitive expedition’ of the British in 1897 to the Kingdom of Benin, a much-discussed case of the intermingling of cultural destruction and acquisitiveness. Colonial violence leads to a collection of dead objects, as Woodruff’s mural shows by way of the masks lying around in the foreground near the edge of the frame.

One result of this ‘dissipation’ of black art is the culturally isolated presentation of works of non-European art in Western museums, to which the panel Parallels seems to refer.46 Judging by the logic of the image sequence, which is continued in the panel Influences with a representation of the impact of non-European arts on modernism, Parallels depicts the sources of primitivism as seen in the art of Modigliani and Miró, among others. As noted above, extending the history of ‘negro art’ to that of the Pacific and Pre-Columbian cultures constitutes a decisive step towards a non-essentialist conception of black art, with which Woodruff crosses the boundaries of the more narrow idea of the ‘Black Atlantic’.47

Furthermore, although this cycle remains a history of black art, the concept of what that comprises is extended beyond Africa and Afro-America and, starting with the panel Interchange that makes reference to antiquity, is always viewed in its relations with other cultures. If Parallels represents the reservoir of forms that modernist artists drew on for their innovations, then Woodruff also transcends in Influences the usual frames of reference of the time by including Wifredo Lam as the spearhead of these artistic developments; he was, as art historian María Clara Bernal Bermúdez observes, ‘agent of transculturation in the visual arts’.48 Woodruff puts Lam – a black modernist who only a few years earlier had subjected the primitivism embraced by the Western artists to an Afro-Cuban reinterpretation – directly adjacent to his European colleagues. Their formal borrowings from ‘primitive’ art are thereby contrasted with the cultural syncretisms or fusions in Lam’s painting. Without constructing an obvious antagonism, Woodruff thus demonstrates to the viewers of his cycle the possibility of a further development of modernist primitivism, one that has a decolonising perspective. This was undoubtedly a stimulating prospect for the African American art students of Atlanta University.

At a time when critics like Clement Greenberg and curators such as Alfred H. Barr were drafting Eurocentric genealogies for white American modernism and its claims to universalism, the politically charged transculturalism of Woodruff’s The Art of the Negro was of vital importance in offering an alternative history of global art from the black perspective. Executed on the eve of the civil rights movement and within the context of a largely segregated art world, Woodruff’s cycle taught his predominantly African American audience not only a different global history of art, but also a history of race relations, their power structures and the earlier battles for the cultural survival of the colonised peoples. From the perspective of today’s discussions on global art historiography, Woodruff’s cycle can challenge art historians to pay attention to artists’ contributions to the transcultural turn in the history of art.