In September 2016 a new space and programme of activity opened at Tate Modern and Tate Liverpool. Since its launch, 200,000 people have participated, with a further 550,000 connecting online. This programme and space is called Tate Exchange.

Tate Exchange is an open experiment that aims to explore artistic processes and practices with the public. It draws together a range of methods, offering a civic space for dialogue and a platform to test and trial new ideas and emergent thinking. It aims to explore the role art can play in society and the value that might have; it seeks to be relevant and attendant to current local, national and international concerns, as well as to connect the art and ideas held within the gallery with all those who take part. It aims to create a closer relationship between the institution and the public as well as attending to new ecologies of practice between the institution and other organisations whose work is central to the project. In doing so, it is intended to open up all of these processes for public and peer critique.

This may appear a highly ambitious range of aims with which to be meaningfully engaged. However, the idea to create such a platform was rooted in ideas developed with cultural strategists Jonathan Robinson and Shelagh Wright,1 as well as in research undertaken in 2006, which reflected on the changes in artistic practices as well as the shifting public attitudes and behaviours towards education and to public institutions in the UK cultural landscape.2 These shifts and the findings from the research were part of the impetus for the development of Tate Exchange, but it was also grounded in ten years of change and learning within and across Tate that involved external and cross-disciplinary input.3 The changes experienced in the UK can now be understood as broad trends on the international stage.4

This essay does not track the history of Tate Exchange (this can be found in Tate Learning Today: Ten Years in the Making, published in 2018) nor does it describe the activity itself with its attendant successes and struggles, since this is outlined in the Tate Exchange evaluation report.5 Furthermore, it is not intended as an exploration of terms or concepts, such as ‘participation’ or ‘socially engaged practice’. Instead, it aims to consider what social, representational and learning methods have been employed in its first year and what values these methods draw upon. As such, the aim is to get to grips with the extended frames of practice that were constructed or improvised in Tate Exchange as it found its feet and to assess what these frames yield; what they tell us about the benefits, problems and complications of creating an open participatory programme of activity and experimentation in the art museum. It seeks to explore if such frames can help form a critique, that is to say, a way of critically creating new practice.6

The programme involves a range of international artists and participating organisations that so far have explored ideas around education, identity, space, exclusion, wellbeing, migration and money. In all projects, talking and making have stood out as key features that have combined in unexpected ways to open up an extended conversation; one that is intimate, institutional, cross-organisational and civic in scope. It is hoped that this extended conversation, and the particular conditions that have helped create it, can be better understood through the frames this essay will set out. They point to the ways in which art and ideas have been a springboard for what appears to be a collective will to construct new shared meanings.

In its first year, Tate Exchange took the theme of exchange itself as its initial exploration of artistic practices and processes with the public, and comprised three phases:

Starting debate: programming by Tate Learning staff with artists, practitioners and theorists.Growing debate: programming by fifty-three ‘Associate’ organisations, many of which worked with artists to implement activity.Reflecting on debate: documentation, research and evaluation activity that sought to comment on, assess and analyse the previous two phases.7

On any day the programme might look different, but has included activities that the public could play a part in, whatever the phase. Sometimes there were discussions and debates taking place, at other times the focus was on making, from tiny objects, to large scale architectural forms. There was dancing, writing, talking, designing, testing, watching, playing etc. There were opportunities for families, projects for schools, and programmes for adults and seniors, available in different formations over time and run by a range of practitioners and artists. All shared the purpose of engaging with the concept of exchange and what it meant today from the social to the emotional, from the financial to the structural; working with art, ideas and the Tate collection to dig dip or reach wide. The space was managed by a range of staff that helped set up a different programme every week as well as look after the space and welcome visitors into the activities.

Underpinning Tate Exchange and the approach to running the programme are core values: trust, generosity, risk, respect and openness. These values have their roots in practices developed by those who set the programme in motion and are very much part of the wider institution in which it is situated. In Tate Exchange the approach is based on a form of creative learning, an invitation to a joyful encounter in the expanded field of arts practice. Learning is often articulated as change through experience – sensory and cognitive, physical and social – that is always in process and variously guided by individual beliefs and values at any given time in any given culture. The key features of creative learning are different and often defined in terms of problem identification, divergent thinking, emotional intelligence, a balance of skills and challenge, risk-taking, refinement of task and the pursuit of a valued goal.8 I would argue for a form of such creative learning that generates the potential for a dynamic interaction between selves and others as an ongoing exchange of questions, ideas, knowledge, attitudes and behaviours from wherever one is situated without an imagined origin or endpoint.9

The commitment to creative learning is perhaps the unspoken core value of Tate Exchange in that it enables and forms the undercurrent of all other values. There are many ideological walls that have been built into the existing idea of a museum that need taking down. One thing Tate Exchange might usefully do is to be transparent about its values so that no new walls are created. Let it make explicit those invisible walls that already exist in order to loosen the grout that cements them. This means that there can be no coercion or imposition of beliefs by stealth, rather an explicit set of values that might be agreed with, challenged, opposed to and, necessarily, be open to change.10

With this in mind international artists were invited by Tate to generate programmes that embodied the values of Tate Exchange, but that also reflected those of the invitees. Then, artists and practitioners from external organisations (Associates) were invited to generate interventions that explored their own set of values, ideas, beliefs and perspectives, as well as inviting a further range of values held by the broader public who participated in the programmes. Since we can never assume to know ‘all’ the public or any individual person within the public then the concept of a homogenised ‘all’ cannot reasonably be said to exist. Indeed ‘all’ may better refer to the array of potential and alternative perspectives held in those that visit the galleries and by extension in those who currently do not. If we cannot account for everyone – their perspectives or what they bring, think and how they behave – how do we go about assessing a single concept of public value in relation to Tate’s and the organisations with which we work? Given that the core aim in Tate Exchange is to explore the role art can play in society and the value that might have, we start our journey with something of a conundrum.

To address this, and find an acceptable means of understanding how to manage and describe an ‘all’, we might usefully begin by outlining the layering of values across and between the institution, artists, practitioners and the public, building an understanding of what, why and how Tate Exchange operated in its first year on the level of values themselves. Three frames are presented below in order to achieve this.

The first frame looks at values themselves and how they were formed in Tate Exchange, the second explores how these were applied in practice, and the third considers the value of these values. Frame 1 borrows from John Rawls’s idea of ‘reflective equilibrium’ as one of several theories that could help account for the development of Tate Exchange and what, on a meta-level, has been taking place within it. Frame 2 is one that I have developed under an umbrella of four concepts, namely space, time, content and method (STCM). This enables comparisons and identifies difference and similarity within and across divergent practices. Frame 3 is written under the banner of ‘For and To’ and creates a means of understanding and questioning legitimised practice; it makes explicit the inherent power relations and the problem of habituated educative, rather than learning, behaviours.

Digital Making Art School with Digital Maker Collective, University of the Arts London at Tate Exchange, February–March 2017

© Tate

Frame 1: Reflective Equilibrium

Rawls’s A Theory of Justice (1971) explores ideas, concepts and practices that draw on historical and philosophical texts as well as language, ethics, law (and much else besides). In the first year of our work in Tate Exchange the idea of reflective equilibrium was drawn to my attention owing to the processes contained in the idea that have strong resonance for, and may give useful insight into, the processes and development of values in Tate Exchange.

The idea can be summarised thus: ‘Reflective equilibrium describes the end-point of a deliberative process in which we reflect on and revise our beliefs about an area of inquiry, moral or non-moral.’11 Assessing and deliberating about what is right or wrong, what one ought to do, or not, are part of everyday life. The foundations of these beliefs may be categorised as those that emerge from values, understood here to mean ‘a judgement about what is important in life’ or the ‘principles and standards’ to which one subscribes.12 Values may be said to be grown from one’s range of experience and exposure to different ideas; the personal, social, geographical, (non-)religious and cultural context in which one lives, as well as one’s relationships to others. These may support and form an undercurrent of one’s daily attitudes and behaviours, as well as the actions that arise from these. In reflective equilibrium, it is the testing of morals and beliefs that takes place and can be done individually or with others. In this, Rawls makes a distinction between what he terms ‘narrow’ and ‘wide’ reflective equilibrium:

A reflective equilibrium that arises through reflection on merely one’s own prior convictions is narrow. A process of reflection that also pays careful attention to the moral conceptions advanced by others – in one’s own and in foreign intellectual traditions – and thereby gives these a chance to influence one’s own convictions and systematisations results in a wide reflective equilibrium.13

A further articulation of reflective equilibrium reveals the unstable nature of the process: ‘Moreover, in the process we may not only modify prior beliefs but add new beliefs as well. There need be no assurance the reflective equilibrium is stable – we may modify it as new elements arise in our thinking.’14 This suggests that the ‘end-point’ (as described above) is not fixed, but is rather a temporary point open to further and ongoing modification. Let us look at how this presents itself by attending to what the theory ‘looks like’ as a process.

How does it work?

The method of reflective equilibrium consists in working back and forth among our considered judgments. The method succeeds and we achieve reflective equilibrium when we arrive at an acceptable coherence among these beliefs. An acceptable coherence requires that our beliefs not only be consistent with each other (a weak requirement), but that some of these beliefs provide support or provide a best explanation for others.15

The aim is to work from an ‘original position’, defined by Rawls as ‘the appropriate initial status quo which insures that the fundamental agreements reached in it are fair’.16 This status quo is one in which ‘no-one should be advantaged or disadvantaged by natural fortune of social circumstance in the choice of principles’.17 The original position, one that Rawls emphasises is ‘purely hypothetical’, has over time invited much critique. However, it is also a theory that invokes a human capacity for change when improved accounts and educated understandings are formed.18 Any process toward achieving reflective equilibrium must also match our values in the way that it is undertaken. One must therefore attend to the constructed understandings of the ‘individual’ or ‘subject’ and challenge notions of what is just and for whom, to create a system in which ‘all’ are equally represented and respected. Despite evident complexities, the lens of reflective equilibrium affords a way to understand the possible processes and navigation of values (and agreeing them to an acceptable level) in the set-up and running of Tate Exchange, as well as a method of interaction with Associates and the public.

Before Tate Exchange began, the Learning team at Tate had undergone a process named ‘Transforming Tate Learning’, which constructed a values-led approach to work. The process involved all Learning team members discussing and establishing a shared set of values. Everyone identified their own focus and motivations in relation to the institution as well as naming personal values that were then consolidated into overarching values for the Learning programme and practice.19 There was not absolute agreement on the exact terms selected but there was a form of acceptable coherence across the piece that resulted in the choice of trust, risk, generosity, respect and openness. Transforming Tate Learning implicitly developed a form of practice that may be said to have had characteristics of reflective equilibrium from the outset.

When we introduced potential Associates to Tate Exchange (organisations that sit beyond Tate and that include those outside the arts) there was a sense of common purpose since we contacted those organisations that we believed would be interested in the proposition of a new public experimental space. Although a handful of these organisations chose not to continue once our values were made explicit, on the whole the values were not challenged. In keeping with Rawls’s approach, we will return to the values with the Associates to revise and review in the future. What did unfold, however, was the realisation that even in agreeing values on paper or in the abstract, when tested in practice they can be found wanting or simply be interpreted differently. That said, the majority have welcomed the principle of a new civic space in which views can be negotiated. Indeed, positive feedback has been extensive, even in relation to difficult conversations. Several Associates reported that they have ongoing issues about visibility and inclusion with many institutions but had never previously been able to have this conversation and appreciated that in this case the opportunity had been given to do so.20 The conversations taking place during programmes frequently generated a highly emotional response; the divergent public, artists and Associate’s appetite for Tate Exchange (warts and all) suggests that a space in which to explore difference is of high value, and is further reflected on below.

Artists, practitioners and the public

In the first phase of Tate Exchange artists were invited to construct a programme either with the public or for the public to engage with and participate in. Interestingly, only one collective opted for the former (with the public from the outset) and even then the programme was designed in a way to invite people to co-construct with an idea already in mind. This perspective may change over time but experience to date suggests that co-construction at its deepest level may be too much to ask for, particularly for those participants taking their first steps into any engagement with art or with only an hour to spend. The artists involved had to navigate a new space and new expectations through the institution and the public and it is evident that some artists struggled to work within a discursive model, operating instead on the basis of transmission. On reflection, it is also clear that the invitation to artists was confusing, as it demanded, but did not always adequately articulate, a different relationship with their work that invited processes rather than product.21 However, others thrived in the conversation and the to-ing and fro-ing of ideas with staff and public alike. There was an opening up of different forms of practice such that learning could take place, not just for the public, but for all involved; it actively changed artists’ practice.22

The Associates’ experience was different in that much more time was given to creating conditions for dialogue. This was mostly due to the fact that we felt that time and space were required for them to become familiar with the idea and the building, although as we discovered, they were at times more aligned to the project in terms of the conceptual frame than some artists. As a result of this positive dialogue with Associates, there were many changes made in the process whereby Tate shifted the direction of the programme relative to ongoing discussions around values. Modifications were introduced to both the idea and how it was implemented that led to Tate Exchange itself being revised with regard to timing, staffing, costs, collaborations and overall perspective, purpose and function. Probably the most impactful of these was the commitment to representations of difference and how the institution needed to both listen and better adapt to this without ‘the indignity of speaking for others’.23 In this, when it came to putting forward and working through their programmes and values, it was clear that for some Associates, other values started to get in the way or be challenged; these were the values that the Associates felt the broader institution held and these became more of an issue than the values of learning or Tate Exchange per se. This is familiar territory in that the dynamics between the institution and programme often live in tension, particularly when change is taking place and many questions arise about the ability of an institution to be involved in forming a critique that implicates itself. This is the subject of my essay ‘Who Will Sing the Song? Learning Beyond Institutional Critique’, and will be returned to in the last frame ‘For and To’.24 What can be said is that the raising of questions around values generated dialogue beyond Tate Exchange as a programme and into the institutional fabric of Tate’s systems, structures and values. We know that dialogue can be difficult, but unless we are prepared to identify values ‘gaps’ and bridge them, then we are faced with stasis, and in the language of Rawls’s reflective equilibrium, unable to form an acceptable coherence.

For the public, most of the talks and workshops created by the Associates as well as interventions-come-happenings (that we have yet to find a word for) involved a two-way debate or engagement of ideas that were openly tested against others, with the active invitation to come and join in, contribute, and exchange ideas. These can also be seen in the small interactions, such as conversations with the public as they entered the space, which though predominantly joyful, did at times present opposition. In these, the dialogue, the to-ing and fro-ing of values, was key to potential participants engaging with the project and changing their minds or the minds of others involved in the project. This also generated opportunity for public perspectives and challenges coming back to the institution that prompted alternative ways of thinking about the programme that were more inclusive and indeed more sensitive to the difference encountered. Although we were attentive to these issues, particularly in relation to race, ableism, class and gender, the experiences generated a far deeper understanding, self-criticality and questioning of current behaviours, systems and structures.

Tim Etchell’s opening piece The Give and Take: Three Tables (2016) was founded on the notion of dialogue between strangers – facilitated conversations structured by a performer that put different people’s perspectives together under a common theme. It opened up cultural and personal contexts and accounts that exposed and reflected on contested ways of thinking. This proved to be a highly productive, emotional participatory experience where the public engaged at length, sometimes for several hours. It was repeated as the closing activity of Tate Exchange in its first year. Again, through the lens of reflective equilibrium, this work can be seen to have generated coherence since:

the conditions for the process of talking were mediated and found to be acceptable by all (via performative structures);the opportunity to contribute was afforded equally;a climate of trust and respect was maintained in small groups by a performer modelling behavior;it was an opportunity to deeply listen and have one’s knowledge and understanding expanded and changed through experience and empathy with others (a ‘wide’ reflective equilibrium).

It expressed the values that had been intended for Tate Exchange and the trust shared by those involved was both unexpected and generous.

Of course, what a theory offers to partially designed processes, or one that is making itself up as it goes along, is the capacity for re-application of modified procedures with anticipated outcomes that can be further tested. For Tate, reflection led to a much clearer revised invitation to artists and a longer period of pre-event dialogue, one that now enables sufficient time to consider an appropriate approach to the purpose of the space and programme. It has revealed a need to be as explicit as possible about values and what they look like as practice. It has emphasised the need to be open to challenge from different views, just as reflective equilibrium demands. It has enabled an improved conversation about complex issues surrounding the institution and what exclusions have been made over time that need changing. It has generated reflections on how this may be addressed and given a process for doing so. Reflective equilibrium as a theory encourages us toward an awareness of institutional actions and behaviours and offers a means to attend to them. Those taking part know this is the beginning of a conversation whereby the various histories underpinning the cultural institutions we work within need to be critiqued. The new responses that arise as a result should more adequately cohere with the experiences and knowledge of others. Generally, this form of negotiating values was welcomed by the public; individuals that have limited opportunity to respond and feed back were given space and time to use their agency and have their views represented. They felt Tate Exchange to be a positive and safe civic space to do so.25 This is an acknowledgement that the ‘fair and equal’ ambitions of the process of reflective equilibrium that Rawls describes, need, unsurprisingly, to operate on an equal footing. It can be hard for any and each of the layers (institution, artists, Associates and public) to avoid transmission of their values and instead enter the programme with exchange in mind. But exchange is vital if we are to reach an acceptable coherence in our approach.

What is missing in this values appraisal is a further layer, which includes funding bodies. All funding we received in year one came from bodies that also had alignment with the project’s aims and values.26 This seems to be an essential requirement; if all parties do not share a full understanding of the programme’s intentions it can be disruptive.

A thorough evaluation programme sat behind the work so that we were able to account for what took place and assess how well we had managed to fulfill our aims. It ensured that we lived up to our stated values and intentions or exposed where we had failed to do so. This was part of the acceptable coherence developed through the values of trust, risk, respect, generosity and openness.

What do we learn from all this? First, that the values of Tate Exchange were welcomed by those involved across all levels, but with the proviso that they need constant review in order to offer clarity in practice. Second, that each layer needed (and continues to need) attending to in itself as well as in relation to the others. Third, that the deliberative process has been transformative. It has made a difference to institutional values as well as to the Associates and (some) artists for whom this experience has changed their practice. The public have also had the opportunity to hold dialogue with artists and the institution. From this has emerged better access to transparent information and programmes, debates and questions that the public has told us makes for a deeper, valued, shared experience (this will be qualified in the next frame below). Lastly, that as a process, reflective equilibrium has provided a useful theoretical frame for understanding at a meta-level how debate on a large-scale platform across registers enables ‘wide’ reflective equilibrium in an open way. Privilege and priority are made visible below the surface of activities; the structures and systems that create them are more fully understood, avoiding a ‘narrow’ reflective equilibrium that invites the artist, individuals or institution into a reflective conversation with itself.

As a process for reaching an ‘acceptable coherence’, reflective equilibrium stipulates that no value has priority over others; all judgments and beliefs can be contested and negotiated. It is a necessary condition to have removed prejudice (or at least for those involved to be able to let go of convictions). For Tate Exchange that implies a new balance between a presupposed historical position of authority with that of standing equally among ‘all’ others. We know how hard this balance is to strike, given the social and political frame in which institutions exist and the extent to which the public has settled into expectations and beliefs that enable those historic presuppositions to persist. The public’s response to co-construction of programme articulates this complexity well in that it exposes the gap between what is expected (what is the organisation’s role and what it is paid to provide ‘for a public’) and how far a sense of any equality can therefore be actualised. Again, this can be explored through reflective equilibrium as an acceptable coherence for those involved, once the dilemma is made explicit. Trust, generosity, respect, risk and openness are values that appear congruent with reflective equilibrium as a process. What becomes clear is the necessity for learning in the process of reflective equilibrium; to be able to change one’s values here is a change that arises through talking and making in which the concept of ‘all’ is held through a commitment to processes that recognise and attempt to navigate difference.

Frame 2: Space, Time, Content, Method (STCM)

If the first frame of reflective equilibrium helps us understand the importance of making values explicit and attending to processes that offer an acceptable coherence, can we dig deeper into the detail of what this looks like when values are applied in practice? What do they look like? The second frame – Space, Time, Content, Method (STCM) – allows this by articulating values within the difference and similarities of multiple programmes across divergent practices. This helps us to gain insight into what works and why and what does not and why not, in any context (and context is a crucial part of this frame). It invites an ongoing movement of focus from the detail to the bigger picture and back to detail again, rather like the process of reflective equilibrium itself.

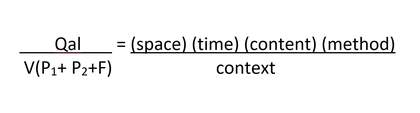

The model: an equation (of sorts)

In this equation, Qal represents the quality of an arts learning experience and is divided by V (values, see above), as multiplied by P1 (the participants) plus P2 (the producers, artists or facilitators managing the experience), plus F (those funding the experience). This quality of experience for an individual, divided by its values and those who shape them, is equal to (definable by) how we construct the use of space, time, content and method, divided by its context. Although this is a bit tongue in cheek and will make real mathematicians’ eyes hurt, it describes the constituent parts that exist in many arts learning experiences, which all need absolute attention to detail, purpose, and the design of the whole. Indeed, each of these constituent parts invites and requires further examination, which we shall explore below.

The model is concerned with an improved integration across all aspects (space, time, content, method, context and values). It gives us a frame to experiment within; it is an opportunity to ask ‘What if we changed P1 or (content)? What would happen then?’ If we have an understanding of our systems of engagement then we are in a position to actively change them for the better, deliberately, in line with our values. This model therefore works as well for planning as it does for summarising activity. For Tate Exchange, this proved a really helpful tool in thinking through how we were going to approach the programme as much as understanding what actually took place and evaluating how it worked and the benefits or problems therein. Before we look at the application of STCM to Tate Exchange, let us establish what is meant by each term, apart from values, which we have established above.

Quality

We all want to be creating the best quality experience in order to be responsible to those with whom we work, and this includes creating the best conditions for effective processes, behaviours, attitudes and understanding, alongside the content and what participants get out of any engagement. And yet we know that quality from one perspective may not be understood as quality from another in the equation; each constituent (participant, producer and funder) may have different interpretations of quality and how this is achieved. Is it in the management of the work? Is it in the moment of experience? Is it in the formulation of the idea? They all matter and they can all have competing demands.

Educationalists Steve Seidel, Shari Tishman, Ellen Winner, Lois Hetland and Patricia Palmer offer a deep, nuanced understanding of quality in their publication Qualities of Quality: Excellence in Arts Education.27 Their analysis outlines six core areas of thought concerning qualities that impact on quality:

The drive for quality is personal, passionate and persistent. The work serves multiple purposes simultaneouslyFoundational decisions matterQuality reveals itself in the roomDecisions and decision makers at all levels affect qualityReflection and dialogue are important at all levels

They also outline the challenges of identifying quality:

The characteristics of quality are multi-dimensional; so we often feel we are capturing some, but by no means all of what we consider the ‘qualities of quality’There is a ‘moving target syndrome’; last year’s excellence may not be adequate this yearContext counts; what feels high quality in one setting may not be in anotherThe subjectivity factor; we each have our own sense of what constitutes quality in arts learning and teaching, and that is always evolving and, itself, contextually boundThe sensitivity factor; talking about quality can hurt people’s feelings, so it can be difficult to talk about honestlyIt’s too ephemeral to talk about! (This is interesting, especially in relation to the report’s findings about the visibility of quality. That is, that almost everyone the researchers talked to said two things – first, quality is too hard to talk about, and second, ‘I know it when I see it’ – which they came to realise suggested that quality is actually visible when one walks into a room in which learning is taking place.)28

What is significant about these qualities is how they relate to the values as explored above. The drive for quality is a values-led endeavour, where planning and expectations of quality and why this is important are described as personal, passionate and persistent and tacitly refer to underpinning values that count quality as an intrinsic requirement of all work. A value is given to the multiple purposes of work and a recognition that decision making about these is values-based wherein foundational decisions can shape the whole and that this is true at all levels of decision making. There is also the observation that quality reveals itself in the room implying a values-led discernment of activity taking place as well as the crucial last point in which it is identified that reflection and dialogue is important at all levels; a process of ‘reflection and dialogue’ such as reflective equilibrium is invited into debates on quality and qualities, and that these are implicit in values themselves.

Space

Space refers to actual and virtual space but is also used figuratively to define intellectual space for thought and ideas. How we think about and create or use space is brought into being through our values (including our sense of quality) as well as creating or diminishing the value of something. For example, a small space with far too many people in it may make for an uncomfortable experience. A pristine room where you cannot make mess when you are working with clay may diminish the experience and limits what you can do. Closed spaces when you need to be open and open spaces when you need to be closed are all issues to be considered. Space matters and articulates a set of expectations and permissions of and for practice; it also helps generate atmosphere and behaviours in a room. You can have the best content in the world, but if the space is wrong for the activity or has the wrong aesthetic ‘feel’ it can blow everything and turn your values on their head. Perhaps the best space for certain projects is online. This should have the same questions around it. Where online? How will this space be curated? Without reiterating the values-led approach again, it is clear that space has values embedded within it. What are we saying about who we are and what we do through space itself? These values therefore need to be made explicit, deliberated, and changes made where required, which itself invites the process of reflective equilibrium.

Time

Time is generally measured in units of hours, minutes and seconds. In many educational environments (and for some dogs participating in behavioural research) this is bell-bound, too. In the context of Tate Exchange, time is considered to be one of the resources available to us that can be expanded or contracted relative to individual needs and experience as well as programmatic demands. There is plenty of learning theory that identifies the intensity of time and the passage of time, which speeds up when there is focus and enjoyment, and which seems to slow down spectacularly to a drag when there is disengagement and boredom.29 Time is understood for the purposes of the equation (of sorts), as one of our most valuable commodities that deserves some rethinking in the learning community. It is particularly resonant in terms of current discussion on the ‘attention economy’, the rise of social media, new technologies in the workplace and the conceptual (and time) gap in the notions of work and leisure. How we value time and our perspectives on this become crucial and might be said to be an issue of respect and generosity.

Content

Content in this model is defined as any subject, theme, idea, material and talk of any description within the space and time of any activity that takes place in a learning environment. It is used as a catchall to describe the ‘thing’ that is being attended to and is included as a focus within a learning experience. Generally, in educational settings success is often measured by how much planned content gets transmitted in any unit of time. In Tate Exchange there is room to consider how content gets generated in an exchange between people; indeed, as we later discuss, how content can valuably meander, transform and become the making of difference. Again, a value is forged in meandering and allowing content to develop rather than transmitting anything fixed. In this case content therefore invites a sense of the new and potential for innovation and fresh or challenging ideas with no pre-formed outcomes.

Method

This articulates the way in which any learning experience is prepared for and undertaken. The approach and all that must be incorporated into this, in terms of attitudes behaviours, values, decisions (including those about space, time and content), as well as practical delivery and implementation techniques. It includes pedagogic methods as well as social methods, scientific methods and institutional methods. It covers a vast sea of possibilities and the potential for new methods that we have not yet encountered or created. What is helpful concerning this wide-ranging term, as with content, is that it enables all different approaches to be put into one basket. However, method also comes loaded with values and these, when looked through the values lens have an alternative set of descriptive categories that may be assigned attitudinal terms in method, such as: generous, expansive, or perhaps punitive or even oppressive. What methods get used and why do they matter?

The concepts of quality, time, space, content and method, as above, will be used in future iterations of the Tate Exchange programme and processes through recourse to the core values (trust, risk, generosity, respect, openness). Each aspect, as signalled by the equation’s brackets, has an impact (a suggestion of a multiplier effect) on each other aspect, such that the use of space will impact on the use of time and the choice of content on the use of method and so on. We probably recognise that getting all the ducks in a row in terms of creating continuity across all aspects is what makes the positive difference and articulates a coherence of values.

Context

Context is defined in the dictionary as ‘the circumstances that form the setting for an event, statement, or idea, and in terms of which it can be fully understood’.30 Following this model, we need to understand, at a minimum, the social, political, economic, physical and personal settings in which we work. Into this we introduce the notion of the public, or artist, or Associate, or funder, who all have their own contexts, demands and needs. I seriously doubt that we might ever come to ‘fully understand’ all that any and every context implies, but in this equation (of sorts) I admit generality in order to expose the vast complexity involved in all environments or experiments that seek exchange between people, places and ideas and therefore point to the relative miracle that anything ever goes even near to plan, let alone is considered a success. There is nothing fixed or absolute in STCM; everything must be considered contingent upon all of the rest.

Applying the model (STCM) to Tate Exchange

With over 400 events and activities in the first year, taking any single examples of projects to explore here will be far too lengthy and inadequate for any overarching understanding. Instead, I shall present how the model was used in some of the detail of our thinking about Tate Exchange for formative and summative analysis, and use examples of projects in a more ad hoc way that helps generalise the principles of STCM use.

Context

In working through the model it is useful to begin at the end, with context. Thinking through what the museum articulates and what meaning is conveyed at any specific site forces one to consider what an idea such as Tate Exchange and the individual programmes and projects within this would add to, complement or complicate. At Tate Modern this was also shaped by the fact that the programme would take residency in a new building. In many ways this was helpful as it signalled ‘the new’ and, as different perspectives of modernism were invited through the rehang of the collection, so too were different perspectives on what social value may be explored through forms of art as participatory activity. Clearly, attendant ideological positions and perspectives were integral to the thinking, with an awareness of invisible walls, forms of institutional production of culture and the contested range of constructed ideas that a museum holds. This framed much of our initial conversations over two years before we started work on the programme and we continue to discuss this on an ongoing basis.

For some organisations coming in to Tate as Associates and programming their own work, this was doubly complicated as it spoke on behalf of themselves and their own contexts, but also through Tate as a further contextual platform, which in some instances was at odds with what they wanted to challenge as part of their practice (see values above in Frame 1). On reflection this was a more complicated state of affairs for those Associates involved with visual arts or more tied in to current discussions in the field as the association with Tate added an additional and sometimes unwanted dimension to their own. For others, they found that the platform offered what they described as ‘neutral’ ground. That is to say, by being out of their physical context new freedoms enabled them to work and articulate ideas, make work and trial practices in new and different ways unburdened by the meanings they left behind, or at least that were invisible to the attendant public on any given day. In this way Tate Exchange offered a means to take away, rather than add preconditioned assumptions.

Tate Exchange activity at times challenged the aesthetic of its context. How does the learning aesthetic of a school relate to that of the art gallery? What do students taking over a space with their art-making convey?31 There were those that found the expanded practice and experimentation exciting in its messiness, and those that preferred debate and tidier forms of exchange such as symposia or talks. As an experiment, we found unexpected (as well as anticipated) kinds of work would rub up against the museum’s context, resulting in perspectives that ranged from concern that the work was too community focused to those who felt it did not go far enough.

What the model offers is a process through which underpinning themes and beliefs are made explicit before any development of a new idea begins. Essential to this was an understanding of how context shaped limitations and affordances, so that one might anticipate and prepare for challenges as well as manage expectations. This was as true for the entire programme as it was for the artists, staff and Associates that generated their work. In this, the values played their part in calling for trust, generosity and respect with regard to getting the new programme into the world, and for all involved with their own programmes. Tate Exchange would never be perfected overnight (if indeed it is ever possible to do so). As is now clear, there are so many elements to consider in any given context, that one might well do nothing for fear of getting everything wrong. This is where the values of risk and openness played their part in encouraging all to take on the challenge. The values effectively created a necessary additional context to Tate Exchange that openly explained and transparently admitted to trialling and potentially failing as part of its condition as an experiment in practice.

Space

Tate Exchange takes place on an entire floor of Tate Modern – a destination of its own on level 5 of the Blavatinik building – whereas at Tate Liverpool it occupies space within the galleries and is most likely to be come across as part of a visit. We required space in which discussion and ‘messy’ activity could take place and where the values could be made real, where risks could be taken and where openness would be evident. This shaped our entire thinking as to how to create an appropriate space for the idea and its content.

Initially, the space at Tate Modern was planned as divided rooms, but as the thinking and values evolved this became less appropriate to the idea and over time the taking down of walls became an obvious and essential need. Huge windows providing a 300-degree view of London gave a further sense of the ‘open’ and porous nature of the idea, but with a spatial configuration that sees the walls taper in, which at points creates sharp triangles of space. This was an environment that was unlike any other and it was initially unclear how it could or might be used. At Tate Liverpool there was a more direct relationship between the art and the programme in that the activity was planned for the gallery space, which invited a difference in experience from the outset; unexpected activity was juxtaposed with looking at art, but making was also more limited owing to the proximity of artworks and the necessity for dry materials.

At Tate Modern we worked with several experts on shaping the space to create the conditions in which we anticipated a different programme or project every week. Ultimately this led us to leaving the space unfurnished and entirely able to be reconfigured at any point; generous in its scale, open, but a risk in terms of the uncertainty of how it might be used. As an unusually large space for learning activity, we also recognised that several programmes would probably want and need to run alongside each other in order for the space to feel ‘full’ or inviting. We had visited Plymouth School of Creative Arts and witnessed how open spaces could effectively be divided while hosting school children. If they could work with several different classes taking place at any one time, open-plan, it seemed possible to do so ourselves.

When thinking about the use of the space programmatically, many at Tate Modern used zones suggested by the architecture, or delineated space through tape on the floor. At Tate Liverpool an artist-made curtain was used to delineate space but became a concern as to how and if this object could be handled, suggesting too much risk. A natural ‘zone’ at Tate Modern emerged as an entrance and for orientation, another for discussion with staff and forms of introduction, yet another for relaxation and social/convivial interactions, and then several others for organised activity and making, showing and performing. On the whole, as one moves round the 300 degrees one encounters quieter or more focused activity. The least successful programmes in terms of space were those that ‘got lost’. It is not true to say that this was always because there was not sufficient activity or furniture, rather that the idea needed to fill or hold the space. Some programmes achieved this with three tables or sets of headphones and tramlines on the floor, while others got lost with an abundance of objects and detail. Where one places activity in space and time matters and generates meaning; an open space with limited activity can feel very exposing for the public to wander in to and take part in unless the idea, space, content, and method are deeply aligned.

The digital space was not as generative a frame as we had envisaged and took on a more transmission-based approach through Instagram and Facebook, video streaming and tweeting. However, much of the digital programme produced by staff and Associates in the physical space did use more generative and collaborative models, which despite permanent daylight, was used to create different atmospheres ranging from high energy to highly detailed intricate compositions appropriate to their choice of content. Where digital methods did make interesting progress was through testing their own limitations; that is to say the team trialled interactions with the public through short story forms and short creative invitations to make and do using Instagram and Twitter to contribute and prompt exchange. More of this is planned for the digital space going forward and is particularly effective in cross-disciplinary interventions.

The uniqueness of the space at Tate Modern and the different use of space at Tate Liverpool, alongside the value that these spaces signified, opened up ways of thinking differently in their physical actuality, not just as a new space for ideas. The scale, light and transparent nature of the space, as well as the predominantly ‘open door’ policy, create a different human choreography in working practices and a kind of visibility that can be exposing when undertaking activities that are not always designed to be seen, such as installing or rehearsing. Of course space, and the ways in which it is shaped to convey meaning, is inevitably conditioned by other factors, so let us now consider another of these: time.

Time

The aim of Tate Exchange is to slow things down and to create time for people to exchange ideas with and about art, to learn, reflect, enjoy or simply be. From the outset we were clear that we did not want anyone to feel forced or obligated to get involved. In doing so we also decided to make the durational offer clear, with ad hoc and not ongoing workshops or courses, more a drop-in range of activities in which you could get more or less involved. We aimed for trust, respect and generosity with a hint of risk always available. This need became clearer still over the planning phase but did not always find its way in to the programmes, where some tried to create the same conditions as those one experiences behind closed doors and with a selected or self-selected public in discrete sessional units of time. Sustaining long courses or a commitment for a drop-in public to return every day is unrealistic (even if there were individuals who returned on a daily or weekly basis). That said, what was surprising was the vast majority of people that came in to Tate Exchange (samples suggest 67%) stayed between half an hour and two and a half hours, some longer. The evaluation reports an average of an hour’s engagement across the piece. This is a huge investment in public time, and signalled an appetite and sense of value for experiences of this kind; but it takes time to create time.

In planning Tate Exchange we aimed to have the space open every day, but in practice we realised we simply could not work all day every day (although we tried!). The festival-like processes are not sustainable 24/7 every day of the year; such a space in the art museum requires more downtime as well as installation periods that can take hours or days. We anticipated that the public would mostly enter into the space after noon and at weekends and our findings broadly supported this at both sites over the year. Conversely, queues could easily form on a Monday before the space was opened if the programme resonated deeply enough with the public.

The idea of slowing down and creating focus might not have been a deliberate intention of those who created programmes, but it was generally observed that all activities sought to, and mostly succeeded in drawing the public into an engagement or an exchange that held their interest and invited them to delve deeper. The qualities of staff that hosted the floor also matched the values, as they actively gave attention to individuals, were expert and respectful in listening and generous with their own time. As indicated above, the ‘orientation’ zone at Tate Modern, for example, offered and invited casual conversation that could and often did travel to unexpected places and came with an instruction that no one need participate. In doing so, we found that permission to do nothing gave unencumbered freedom to try something out and to take as long or as little time in anything, from listening to a talk (spatially designed so that people could come and go without judgement) to making a tea house, being part of a hacking session, or joining in the creation of a dance piece. Taking agency to act or not act and to take one’s own time in one’s own way, to invite flow but not to demand it, generated the conditions in which the values and content could thrive.

Content

The requirement of Tate Exchange was to take the theme of exchange itself as the core content and relate it to works on display at Tate. This took so many shapes and forms that it was not always entirely clear in practice what the actual content might be. In planning, we had not adequately anticipated this range (one of the many things we learned) as the programmers very swiftly moved towards key issues that people wanted to explore, through exchange and with the collection, to a greater or lesser extent. For example, there were those who took on the idea of a meta-exchange with the institution itself, those who looked at the micro-exchange of individuals from particular communities, and those who used exchange as a ‘given’ for exploring a particular idea. Some Associates visited the collection and based their ideas on the works but never made this explicit, while others went to visit the works and explore their particularity in a variety of exchanges through making, talking, dancing, writing, tasting or theorising. Others made the entire collection, or even the notion of art itself, the subject of their exchange, while some took the works in the collection as a backdrop and some did not attend to this aspect at all. For members of the public the more important content was sometimes in the discussion and friendships they made in the space through conversation and new content was generated through casual exchange of informal ideas rather than those set.

During the process we shifted from anxiety to concern, from concern to acceptance and from acceptance to enthusiasm for the range of content that was being generated. If the whole point is to illuminate what value art contributes to society then inevitably one will see a movement beyond the specificity of art into the broader nature of the public’s experiences. On reflection, one can observe our slip into the default model as outlined in the content definition above, in which the set ‘task’ of communicating the desired (or planned for) content in a unit of time became the valued objective, whereas the different value of creating relevant and publicly shaped content, which took unexpected directions and generated new content, was initially not given its due. Again, this returns us to questions of value and of contended value in terms of the expectations of an organisation whose job the public may feel is to provide artistic content that can be consumed or, alternatively, to share ownership with the public on what content could be generated, as new ideas, people and skills interacted through the exchange that took place. Of course, these need not be considered in tension with one another; Tate Exchange should be understood as a space for encountering both.

Method

This leads us to explore what method was planned for and to compare that with the methods that were actually utilised. An overarching way of working is provided by the nature of Tate Exchange itself, being a means of exploring through participatory practices. Already this is open to a wide range of interpretations. Chrissie Tiller has offered a very useful articulation of this, which takes us from (in a colloquial sense) ‘I’m present and so participating’ to ‘I’m creating, making and running this as an artist’.32 The question to ask is, what do we want anyone to get out of any activity? Why would it be ‘better’ to have a more hands-on participatory experience than an observed encounter? Would it be better?

Our experience is that ‘all’ the public (individuals) want, need and like something slightly different, and so the potential problem of having so many diverse methods including workshops, talks, immersive gatherings, demonstrations, debates, making activities, thinking activities, performances, writing, dancing etc. was in practice a huge advantage. It invited the widest range of people to try out different forms or select those they felt most comfortable with. For some, participating as an observer was welcome while for others helping to shape the content was key.

For individual programmes and activities the issue is different. Depending on the content that people choose to explore, the method of approach matters. An approach that is enjoyable and with interesting content can sometimes override issues of space and time (with a fair wind and generosity of participants on your side). If one wants to discuss an idea, then silent making is probably not the best approach to take; if one wants to share skills in making, but only talks, then the learning opportunities might be limited. I would argue that any experience in which people are able to learn or share is optimised through enjoyment, positive emotional experiences, as well as through activity that stretches, but is not out of reach, of those that one seeks to engage. We are not trying to create conditions that put barriers in the way of learning or that test the endurance of individuals, nor are we wanting to generate activity that replays what one already knows; this would challenge the concept of learning itself, although equally we know that this often takes place.

In summary, the model invites a process that encourages all aspects to be thought through before one begins any programme, assessing and modifying as it takes place, and reflecting on what aspects worked best (or did not) so as to make changes and improvements in the future.

What, then, do these frames tell us about the purpose of the work undertaken in Tate Exchange? Have they illuminated the value of art and its roles in society? Has Tate Exchange enabled a closer relationship between the public and the institution and indeed those with whom it has worked over the last year?

It is instructive to consider space, time content and method in relation to Tate Exchange in its first year. In terms of space, the giving over of an entire floor of a new building to learning speaks to a high value placed in this endeavour that, through feedback from the public and through the Associates, was recorded as well received. One participant commented, ‘Thanks to Tate for giving space’, while another commented, ‘this space is a massive gift’.33 It can also be measured in the sense that a new space specifically for civic engagement was created, and for a wider public than the regular gallery visitor; this can be quantified through numbers, and shows an additional 100,000+ participating in learning activity in the space with an additional 200,000 online. In short, more people are having more opportunity.

The unexpected length of time spent by participants on the floor (assessed at an hour across the piece, with 67% staying for over twenty minutes to two and a half hours) suggests a high value in terms of engagement by the public and appreciation of being able to take time, to sit and watch and reflect. As the evaluation reports, ‘Time, time is really important, always rushing about … but taking time out that's what we need’.34

Since much of the evaluation report reveals what was learned, I shall summarise by saying that the report suggests a significant amount of social, attitudinal, emotional and cognitive changes through experience took place for those taking part, as well as professional and pragmatic changes for artists and organisations including Tate.35 In these ways the content of the programme was felt to be relevant to people’s interests and current issues, and able to be applied beyond the moment. Since the value of the content was deliberately intended to diverge from a unit of transmission into a reciprocal exchange, we can see that this too was evidenced and valued in the report, wherein the highest percentage (74%) of those participating was attributed to having their ideas, views and contribution valued alongside conversation (65%).36 Method was measured against how the experience was received, with much positive feedback about opportunities for talking and making as well as the general feel of the experience, which we were regularly informed was positive: ‘Really kind and generous feeling, lots of sharing of ideas and supporting each other.’37

However, this does not stand as a fixed, holistic public view of value, rather it is the navigation between values that creates a sense of overall benefit: the sense that value is generated through the to-ing and fro-ing of different perspectives and having this respected. I would argue that what emerges is a clearer understanding as to the value of values (to borrow from the Qualities of Quality, referred to above) and of the conversation that this has encouraged. The outstanding (and personal) observation through having experienced a year of Tate Exchange is that the conversation is qualitatively different from any of my previous experiences in learning programmes, and I would argue that this is because the dialogue across the registers, the levels and layers of contributors (participants, artists, Associates, funders and organisations) has created intimate and personal conversations, artistic conversations, institutional conversations and civic conversations. The following comments from visitors endorse this idea: ‘London is a place where people don’t talk to each other. London needs more places like Tate Exchange. It should be the face of London’, and, ‘Art is an invitation to a conversation’.38

The last frame, below, looks to explore this unexpected finding of the extended or ‘multiple’ conversation that Tate Exchange has helped orchestrate, and to interrogate further the value of values. In this last frame I return to the question of ‘all’ and ask for and to whom is the project responsible?

Frame 3: For and To

Let us imagine a discussion between two adults concerning young people involved in creating a project for Tate Exchange. In this, two perspectives effectively represent responsibility ‘for’ and ‘to’ the young people.

In arguing responsibility ‘for’, it becomes clear that this will limit young people because to be responsible ‘for’ them is unhelpfully hierarchical and as such most, if not all, of the values of Tate Exchange are lost (risk, trust, generosity, respect, openness). The effect of this is paralysing, with young people becoming a variable to be contained or controlled. They cannot take risks (too dangerous as they become ‘our’ risk that we cannot control). They cannot be trusted (in case they fail unreasonably; this would be our risk and represent our failing). Those responsible ‘for’ the young people cannot be generous (as this simply increases risks already described; the result is a loss of respect in the young people’s own capability and ability to take on responsibility). Not to mention the way in which the young people are being spoken ‘of’ which is, by definition, not an open or respectful exchange.

The alternative perspective represents a responsibility ‘to’ the young people and to the idea of Tate Exchange. If the aim is for young people to gain experience and learn through creating their own activities – to take ownership and experiment in a safe environment with guidance, and to share this through activity with the public – then to be true to the project and to be responsible ‘to’ the idea that the young people should be able to meet the aims set, they would have to take risks and control; responsibility and authority would have to be handed over to them. In equal measure the young people would then have a responsibility to Tate Exchange and to the public; it would share and exercise responsibilities as a common, rather than an authoritative concern. Even if borne of ‘good’ or protective instincts, ‘for’ takes on a power that maintains attitudes and behaviours, ‘to’ insists on respect and invites a call-and-response that may step into the unknown but on a shared journey of mutual trust.

In I Love To You, Sketch of a Possible Felicity in History (1996), the French theorist Luce Irigaray presents an image of relations in which the other is not ‘reduced to that of an object’.39 She presents an offer of love ‘to’ an individual, thereby removing the suggestion of ownership or the other as some form of property. Although this idea is formed in relation to sexual difference, it can usefully be applied to any concept of an/other and may be helpful to us in this context. If the first frame exposed the need to have a level playing field of values through the process of reflective equilibrium, and the second, that these will be lived out through space, time, content and method, depending on context, then establishing how one responsibly positions these values in Tate Exchange is essential.

Being responsible ‘for’ someone or something brings with it a range of associated aspects, from a sense of emotional burden, to that of privilege and power, and can have a totalising impact. It implies a problematic binary of ‘us’ and ‘them’. Debates on this matter are not new. In 1989 literary theorist Trinh T. Minh-ha gave an overview of the issue from an anthropological perspective, describing the interaction as being ‘mainly a conversation with “us” about “them”, of the white man with the white man about the primitive nature-man in which “them” is silenced. “They” always stands on the other side of the hill. Naked and speechless’.40 Her perspective is shared and extended throughout a range of disciplines concerning representation of the ‘other’, particularly in terms of gender, class, race and sexuality in which ‘othering’ is widely debated. This comes with the counter argument of the need to be responsible to speak out against the oppressions of others. What can legitimately be spoken of? Is there ever an acceptable case in speaking for?41 Despite the long-term debates around the notion of the other, it remains a key current concern and one suspects that this, ironically, is owing to the nature of power relations of knowledge between ‘us’ and ‘them’.

In education, the idea of ‘for’ is evident through a system based on what ‘we’ think ‘they’ (students) should know. This is guided by fields of professional knowledge, the various discourses and understandings therein, personal bias, and ideologically driven perspectives, shaped through values, as explored above. ‘For’ therefore suggests an overarching responsibility in educational situations that takes all ownership, decisions and agency for what and how to learn into the hands of the ‘we’. As is evident from Irigaray’s call to love, this might be done with the very best and most loving of intentions, but that emerges from a culture and language that tacitly assumes power over others. In education, there is little space for the learner to create their own knowledge or shape that which they receive, it continues to be held and shaped by others and as discussed, has the potential ‘indignity of speaking for others’. The ‘we’ invoked looks very much like those who hold control or who have an assumed authority. What if we changed our understanding of responsibility to the original meaning of the word, which is ‘to respond’ and engage in a process more aligned to Irigaray’s responsibility ‘to’ rather than ‘for’?

However, there is often high expectation for organisations and institutions to be responsible ‘for’ the public’s engagement, ‘for’ young people, or ‘for’ the public’s enjoyment, and to a certain extent we have to understand that some responsibility ‘for’ others is necessary (such as for people’s safety or for the protection of children). That said, the potential indignity of speaking for others or ‘for’ a specific or dominant view on culture is not congruent with Tate Exchange values, nor with the idea of a reflective equilibrium. Even if we acknowledge that some publics do want ‘us’ to take absolute responsibility and provide activity ‘for them’, this needs to be resisted in the face of an acceptable coherence in the exchange and deliberation of values if we are to be authentic to the project as the example above outlines. ‘For and to’ makes explicit the inherent power relations of responsibility and exposes the problem of habituated ‘educative’ rather than ‘learning’ behaviours that may unconsciously be legitimated, but results in unchallenged issues and the maintaining of normative practices.

Only when we understand and respect other perspectives and values can we start to make a better response and commit to a dialogue in which ‘we’ might recognise the need to change, in order to respond to needs, rights, wants and values of others – ‘they’. The responsibility inherent in ‘to’ will present much unfamiliar territory, as well as the relinquishing of some ideas, beliefs, and convictions. In turn this will inevitably demand the relinquishing of power on the part of those who speak with the privilege of dominant values, which after all is what we learned from our first frame and why Tate Exchange is an experiment in many types of practice, not just those that are artistic.

Conclusion

The initial exploration on values posited the idea that learning, or a certain approach defined as creative learning, was the core value in that it implied all other values ascribed to Tate Exchange. Through the three frames presented – locating learning between all involved, and between aspects such as space, time, content and method, rather than on behalf of or with priority to any one part – we consider how exchange itself creates the conditions for learning with each other and in relation to one another. It requires that we resist totalisation, accepted educative methods, and priority to ‘our’ own positions, convictions and values. In this, I take it as read that my own perspective here is generated though a dominant, Western discourse that is ripe for critique. All of this demands change in accepted attitudes and behaviours. The three frames invite us to make such change possible and it is through practice and experimentation rather than theorisation, in this instance, that dislocations between thinking and doing are exposed.

To explore changing and competing values as a means of understanding value and the role that the arts may have in any social context (and this can never be stable or the same in any local or national culture) confounds almost all we have come to understand as the norm. It requires considerable effort in thinking and behaving differently in order to confront dominant ideas, discourse, language and practices. So this is the opportunity and the challenge of such a programme: to be responsible ‘to’ this idea, and to reshape and reimagine Tate Exchange each year, navigating and changing our values and therefore the programme and operations, including time, space, content and method, such that an acceptable coherence can be sought; one that invokes an ‘all’ that has the dignity to learn, to put aside convictions and be open to change.