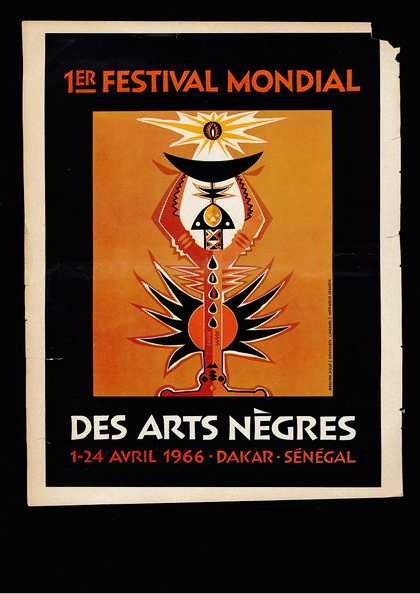

Fig.1

Ibou Diouf

Poster for the First World Festival of Negro Arts, Dakar, 1966

Collection PANAFEST Archive, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris

In April 1966 thousands of artists, musicians, performers and writers from across Africa and its diaspora gathered in the Senegalese capital, Dakar, to take part in the First World Festival of Negro Arts (fig.1). The festival marked a highly symbolic moment in the era of decolonisation in Africa and the push for civil rights in the United States. In particular, it was designed as a showcase for Senegalese president and poet Léopold Sédar Senghor’s concept of Négritude as the fundamental expression of black identity – one that highlighted rhythm, spontaneity and emotion, and also a certain understanding of art as high culture. The visual arts, poetry, theatre, and classical and folk music were all celebrated, while modern, popular cultural forms such as pop music and film were relegated to the margins. The Dakar festival inaugurated a number of major pan-African cultural festivals across the following decade: the First Pan-African Cultural Festival (PANAF), held in the Algerian capital Algiers in 1969; and the Second World Festival of Black Arts and Culture, better known as FESTAC, that was the follow-up to the Dakar event held in Lagos, Nigeria in 1977.1 There is now a growing body of research on these and other, smaller festivals, which are increasingly recognised as significant events in histories of the development of cultural pan-Africanism in the second half of the twentieth century, but which have formerly been neglected by those histories.2

This article traces how the understanding and expression of a unified global African culture and identity, as it was imagined by many of the organisers and participants, evolved across these three pan-African festivals held in Dakar, Algiers and Lagos. Equally, there were those present who questioned this notion of a single, shared African culture and who offered dissenting voices in relation to the official, celebratory discourse of the organising nation state; the ideas of both camps will be explored here. In much of the literature on these festivals, it is the ideological differences rather than the similarities between them that are generally highlighted.3 After outlining Senghor’s conception of Négritude and how it informed the aims, structure and reception of the Dakar festival in 1966, this article explores the differences between Dakar and the subsequent events in Algiers and Lagos, while also suggesting that there are profound continuities underpinning their desire to perform pan-Africanism for their audiences. Furthermore, I will argue that in order to foster a more complex understanding of these events, we must refuse the temptation to view them solely as top-down, monolithic, univocal expressions of the state-sponsored national cultural vision that underpinned them. We must view them just as much as bottom-up events in which individual actors and small groups forged their own sense of an unofficial, lived pan-Africanism. In the case of Senghor’s Senegal in 1966, that means refusing to accept as a given the notion that the Dakar festival was a clear-cut and universally accepted celebration of Négritude.

Senghor, Négritude and a pan-African culture

Fig.2

Jazz musician Duke Ellington performing on stage at the national stadium in Dakar as part of the First World Festival of Negro Arts, 1966

Collection PANAFEST Archive, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris

Fonds Jean Mazel

In 1930s Paris, Senghor and a group of fellow young black students from Africa and the Caribbean had been inspired by the Harlem Renaissance – the intellectual, social and artistic movement that flourished in the 1920s in New York and other parts of America and saw the self-confident celebration and expression of black culture. Senghor and his circle responded to this by launching the Négritude movement, which sought to promote black pride among France’s colonial subjects. The Harlem Renaissance and the jazz age would always retain a special place in Senghor’s heart and this was reflected in the Dakar festival over thirty years later. Indeed, the list of Dakar participants reads like a who’s who of some of the greatest African American cultural figures of the early and mid-twentieth century: Duke Ellington (fig.2), Langston Hughes, Josephine Baker, to name just three.

Senghor and his circle, in particular the Martinican Aimé Césaire and the Guyanese Léon-Gontran Damas, revelled in their emotional, cultural and intellectual discoveries of each other as representatives respectively of either a ‘lost’ Africa or of a diaspora that had been torn away from the African homeland. They each belonged to an emerging black elite within colonised society whose education was designed to assimilate them into the ‘superior’ civilisation of the French Empire. Each of them in their different ways experienced this process of assimilation as something that increasingly alienated them from the black culture of their childhoods: Négritude was their response to this feeling of alienation, a return to their (imagined) roots that celebrated Africa, emotion, rhythm and spontaneity as the antithesis of a cold, European rationalism. As Senghor (in)famously stated in ‘What the Black Man Brings’, an essay written in 1939: ‘Emotion is black, just as reason is Hellenic’.4 The Harlem Renaissance offered them a model of a general cultural revival that promoted solidarity and belonging, and Jamaican writer Claude McKay’s roiling 1929 novel Banjo: A Story without a Plot, about the black working class community in Marseilles, was a particular favourite (it had been translated almost immediately into French).5

Négritude was never a monolithic concept, although in the post-war period it would increasingly be associated with Senghor, who obsessively revised, reworked and generally expounded upon it at great length across a series of speeches and essays.6 While Césaire, Damas and other black poets and writers were happy to explore the possibilities and limits of Négritude as a means of expressing a shared sense of blackness, Senghor sought to construct an intellectual scaffolding for it. In addition, it was he who consistently flirted with more essentialist notions of identity that led the poetic imagery of black spontaneity and rhythm towards a more fixed vision of black identity, one that his post-war critics decried for its ahistoricism and lack of political awareness.7

The relationship between Senghor’s Négritude and pan-Africanism was generally quite fraught. In the era of decolonisation following the Second World War, Senghor was cast by his enemies as a friend to the former imperial powers of western Europe, while Négritude was deemed to be solely cultural, with nothing to contribute to the political sphere. The Senegalese poet-politician thus stood in stark contrast to the figure of Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah, whose desire to create a United States of Africa and general friendly outlook towards socialism made him a dangerous figure to the Western powers.

Despite such political differences, it is my contention that Négritude and the First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar constituted very specific expressions of pan-Africanism. Négritude and pan-Africanism are, of course, not wholly interchangeable terms: the former implies a racial understanding of Africanness that is absent from some of the broader geopolitical constructions of a pan-African identity. Indeed, the 1966 Dakar festival revealed some of the tensions between Négritude and these broader understandings of pan-Africanism, as North African nations were given observer status and excluded from official festival competitions. Although some North African artworks were exhibited and there were performances of music and dance, including a concert by the Tunisian singer and writer Taos Amrouche, North Africa was deemed by Senghor to be fundamentally different to the black civilisation that the event was designed to celebrate. However, such tensions do not make Négritude and pan-Africanism opposing concepts either, for the latter term has always been malleable, available to those keen to give it a racial or a geopolitical meaning.

The concept of pan-Africanism came into use in the nineteenth century as a way of attempting to forge a common bond between Africans and those of African descent (primarily) in the Americas, one that might transcend the historical catastrophe of the Atlantic slave trade and Europe’s growing domination of what it viewed as the ‘dark continent’. In the first half of the twentieth century pan-Africanism inspired the writings of key black intellectuals such as W.E.B. Du Bois and George Padmore, who sought to ‘reunite’ the black world through a series of major congresses in Europe. Following this, in the era of decolonisation, figures such as Nkrumah aimed to give tangible political form to the pan-African ideal through the attempted creation of the aforementioned United States of Africa. Nkrumah’s brainchild, the Organisation of African Unity, proved unable to drive greater African integration and, in a rather grim irony, the Ghanaian was overthrown in a coup d’état in early 1966, shortly before the Dakar festival. It is therefore hard to resist the temptation to view the Dakar event as the moment when pan-Africanism as a political project lost ground to pan-Africanism as a cultural project. In statements about the Dakar festival, Senghor expressed a desire for Senegal to be perceived as the ‘second homeland’ for all black visitors,8 a concept of transnational citizenship that would be pushed even further in both Algiers and Lagos, as will be shown below. The Dakar Festival was thus very much a pan-African event, but one that was underpinned by the racial logic and poetic imaginary of Négritude.

The First World Festival of Negro Arts, Dakar, 1966

On 30 March 1966 Senghor ascended the steps of the National Assembly in Dakar to launch a colloquium on ‘The Function of Negro Art in the Life of, and For, the People’. The colloquium was seen as the intellectual fulcrum of the festival, which would officially begin two days later on 1 April and run until 24 April. That Senegal should hand over its legislative chamber for more than a week to writers, performers, artists and scholars to discuss the role of art in the emerging post-imperial world was entirely in keeping with the central role that Senghor attributed to culture and the arts. In his speech Senghor declared:

We deeply appreciate the honor that devolves upon us at the First World Festival of Negro Arts to welcome so many talents from the four continents, from the four horizons of the spirit. But what honors us most of all and what constitutes your greatest merit is the fact that you will have participated in an undertaking much more revolutionary than the exploration of the cosmos: the elaboration of a new humanism which this time will include the totality of humanity on the totality of our planet Earth.9

Political pan-Africanism had dominated the pan-African movement from 1900–45 in the aforementioned series of landmark congresses in London, Paris, Brussels and Manchester. These events saw political activists, including heavyweight figures such as Nkrumah as well as Du Bois and Padmore, seeking with growing self-confidence to promote the cause of black rights both in Africa and the Americas. In his Dakar festival speech, however, Senghor promoted cultural pan-Africanism as the truly revolutionary dimension of the black contribution to an emerging post-imperial world.

The festival was a modern cultural event on an unprecedented scale in Africa and, as its official title suggests, the organisers were keenly aware of its ground-breaking status. It may not have been the first transnational black cultural gathering – the preceding decade had witnessed the celebrated Congress of Black Writers and Artists in Paris (1956) and in Rome (1959); African writers gathered together for a congress at Makerere University in Uganda in 1962, while that same year an International Congress of African Culture was held in Salisbury in Southern Rhodesia (now Harare in Zimbabwe). Yet the Dakar event represented the first time that a festival celebrating black culture had been organised on this scale. That such a grand event should take place in an Africa gradually liberating itself from a century of colonial rule was symbolic of the growing sense of a new dawn for the continent. On a more pragmatic level, the festival would also allow Africans to discover more about each other, as well as forging greater links with the diaspora.

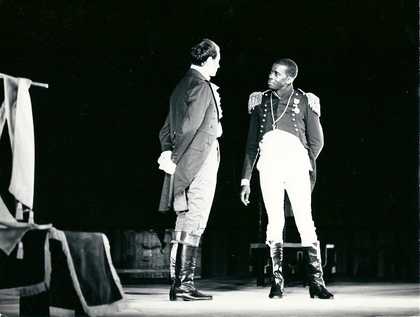

Fig.3

Performance of Aimé Césaire’s play La Tragédie du roi Christophe at the Sorano Theatre, Dakar, 1966, as part of the First World Festival of Negro Arts

Collection PANAFEST Archive, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris

Fonds Jean Mazel

Fig.4

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater performing at the Sorano Theatre, Dakar, 1966, as part of the First World Festival of Negro Arts

Mercer Cook Papers, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University

Representatives from thirty independent African countries gathered in Dakar, and several countries with significant African diasporic populations were also represented: the United States, Brazil, Haiti, Trinidad and Tobago, the United Kingdom and France. The scale of the event developed far beyond the original plans for a gathering of writers and intellectuals and became a sprawling event spanning literature, theatre, music, dance and film, as well as the visual and plastic arts. It was held in a series of locations around the city, and some of the most high-profile events took place in a range of newly built venues: the Sorano Theatre hosted performances of plays by Wole Soyinka (Kongi’s Harvest, 1965) and Aimé Césaire (La Tragédie du roi Christophe, 1964; fig.3), as well as nightly shows of music and dance, including the Alvin Ailey troupe of African American dancers (fig.4); the Musée Dynamique was home to a major exhibition of Negro Art; the refurbished Centre Culturel Daniel Brottier hosted theatre, music and dance; and the Palace Cinema was the venue for the somewhat marginalised film component of the event.

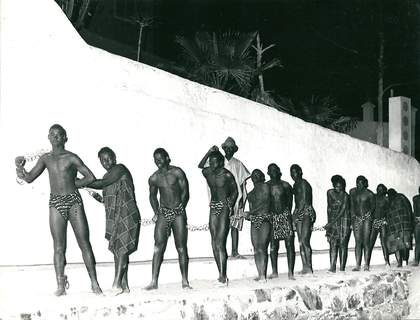

Fig.5

Performance as part of the Spectacle féerique de Gorée, First World Festival of Negro Arts, Dakar, 1966

Collection PANAFEST Archive, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris

Fonds Jean Mazel

Fig.6

Performance as part of the Spectacle féerique de Gorée, First World Festival of Negro Arts, Dakar, 1966

Collection PANAFEST Archive, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris

Fonds Jean Mazel

Other strands of the festival saw non-arts venues pressed into service: as mentioned above, the event was formally launched at the National Assembly where the official festival colloquium took place; there was a modern art exhibition at the Palais de Justice (the law courts); musical and theatrical performances were held at the National Stadium; the African American gospel singer Marion Williams performed in the cathedral; Dakar’s town hall was the venue for a modest exhibition on the festival’s ‘Star Country’, Nigeria; and the son et lumière show on the beachfront at Gorée, entitled the Spectacle féerique de Gorée, brought the festival out onto the city streets (fig.5). A highlight of the festival, the Spectacle féerique was produced by French writer and filmmaker Jean Mazel, and its accompanying text was written by Haitian author Jean Brierre, who was living in Senegal as a refugee from the Duvalier regime – yet another striking example of pan-Africanism in operation. The Spectacle féerique presented a series of tableaux recounting the history of Senegal, through to the slave trade and colonialism, culminating in the nation’s recent independence from France in 1960 (fig.6). It took place almost nightly during the festival and reports indicate that it was seen by over 20,000 people in total, which suggests an audience of approximately 1,000 each night.

Fig.7

Musée Dynamique, view from the beach at Soumbedioune Bay, Dakar, 1966, during the First World Festival of Negro Arts

Collection Roland Kaehr, PANAFEST Archive, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris

Fig.8

Installation view of the Negro Art exhibition at the Musée Dynamique, Dakar, 1966

Collection Roland Kaehr, PANAFEST Archive, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris

Fig.9

Installation view of the Negro Art exhibition at the Musée Dynamique, Dakar, 1966

Collection Roland Kaehr, PANAFEST Archive, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris

The festival may have featured a wide array of cultural forms, but for Senghor its centrepiece was the exhibition of Africa’s ‘classical’ art at the specially constructed and dramatically situated Musée Dynamique, perched above Soumbedioune Bay (fig.7). The exhibition witnessed the apparent juxtaposition of so-called traditional African arts and European high modernist art, which was designed to illustrate both difference and complementarity. Senghor had deployed his political and cultural capital to bring to Dakar some of the finest examples of ‘traditional’ African art: that is, African masks and sculptures borrowed from the collections of Western museums such as the Musée de l’homme in Paris and the British Museum in London (figs.8 and 9). These were exhibited alongside works by European modernists such as Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger and Amedeo Modigliani, in what must have been a fascinating display of traditional African sources and some modern masterpieces inspired by them.

Much of the credit for arranging the loans for this exhibition is owed to Senghor, who was viewed as a reliable partner by the West: although this very reliability was perceived by his critics as proof that he was a neo-colonial lackey.10 But the efforts that must have gone into its organisation were worth it for Senghor, who saw the exhibition as ‘the real essence of the Festival’ due to the correlation that it revealed between what he termed ‘the classics of Négritude, on the one hand, and on the other hand the contemporary art of Picasso and his followers’.11 It is significant that it was traditional African art that was elevated by Senghor to the status of high art. Meanwhile, at the Palais de Justice, an exhibition of artworks by young African painters left him ‘disappointed’, but he understood that these were the first stumbling steps of a new art attempting to engage with Western modernity in a new visual language.12

The exhibition of African art at the Musée Dynamique also played a crucial role in Senghor’s conception of the festival because it ‘reunited’ many of Africa’s ‘classic’ works of art under one roof for the first time. In his writings he had worked for decades to define an African ‘classical’ age that might act as inspiration for the future. The classical art on display in Dakar illustrated the essence of what he considered the essential genius of black civilisation (its Négritude) and it would inspire a new renaissance to be driven forward by the artistic community that had gathered in Dakar.

A few months before the festival, Senghor underlined this ‘classical’ theme in a speech to the annual conference of his political party, the UPS (Senegalese Progressive Union), making remarkable comparisons between contemporary Senegal and ancient Greece:

[The Greeks] lived in a poor country of narrow plains and rocky hills. But, like the Senegalese people, they had the sea beside them, cereals on the plains, oil in the hills and marble in the soil … They sacrificed everything for the love of liberty and truth, for the love of life and beauty … That’s why, as long as Men are alive on this planet, they will speak of Greek civilization as a world of light and beauty.13

This is, in many ways, a typical piece of exalted prose by Senghor, far removed from the day-to-day concerns of his people, although it was also a canny piece of political stage-management, announcing for his homeland a significance that belied its size. If Senegal was comparable to Greece, then its equivalent to Rome was Nigeria, a country which, as the rest of the speech makes clear, wins hands down in terms of the quantity of cultural outputs; however, Senegal has nothing to envy Nigeria in terms of quality. In addition, despite Senghor’s love of abstraction and la longue durée (the idea that culture evolves across millennia rather than decades or even centuries), the festival and not least the exhibition at the Musée Dynamique were built on hugely impressive diplomatic and practical achievements. In its complex mix of the utopian and the pragmatic, the First World Festival of Negro Arts was thus a striking example of an approach that historian and anthropologist Gary Wilder has identified as central to the post-war thought of both Senghor and Césaire. Wilder focuses on the period 1945–60, and the ultimately failed attempt to construct a federal solution that would tie France to its former colonial possessions in what Wilder calls ‘pragmatic-utopian visions of self-determination without state sovereignty’.14 Yet his analysis is applicable to Senghor and Césaire’s (equally fraught) attempt through the festival to construct a transnational black community. As Wilder states:

[Césaire and Senghor’s] projects were at once strategic and principled, gradualist and revolutionary, realist and visionary, timely and untimely. They pursued the seemingly impossible through small deliberate acts. As if alternative futures were already at hand, they explored the fine line between actual and imagined, seeking to invent sociopolitical forms that did not yet exist for a world that had not yet arrived.15

Wilder’s reading of Senghor’s and Césaire’s transnational political imagination in the post-war period invites us to look beyond the ultimate ‘failures’ of their project and its perceived lack of realism. Their willingness to imagine a post-imperial world outside the confines of the nation state or the hegemony of Western imperialism may have been unsuccessful, but it offered models and ideas – a commitment to transnational forms of community, and a focus on culture as the best way to forge that community – that continue to inspire many black people both in Africa and the diaspora. The festival was an effective performance of pan-Africanism quite simply because it drew black people together in ways that had not previously been possible, allowing them to imagine new creative and affective connections that spanned different black communities across the Atlantic.16

Dissenting voices

As indicated above, the participation of the US delegation in Dakar in 1966 was of particular importance to the Senegalese president, as the Harlem Renaissance and jazz had played a formative role in his creative imagination since he first encountered them in Paris in the 1930s. In turn, the festival’s significance as an historical event was not lost on African American visitors. The radical African American journalist Hoyt Fuller, editor of the Negro Digest and one of the most astute commentators on the festival, reflected excitedly that:

There had never been anything quite like it. From four continents and the islands of the Caribbean, thousands of people with some claim to an African heritage converged on Dakar, Senegal, the glittering little cosmopolitan city on the western-most bulge of Africa, and there they witnessed – or took part in – a series of exhibitions, performances and conferences designed to illustrate the genius, the culture and the glory of Africa.17

It did not go unnoticed at the time, however, that the choice of participants largely favoured an older generation of artists, who were viewed as more politically and aesthetically conservative by many of the younger generation. Fuller noted general puzzlement at ‘the absence of the most exciting of America’s black intellectuals’, such as Amiri Baraka, Ossie Davis and James Baldwin, and equal bemusement at the choice of musical artists: ‘Painter Amadou Yoro Ba, a jazz aficionado, asked why musicians like Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk did not come to Dakar, and half of Senegal seemed to have assumed that Harry Belafonte should have been present’.18

Such artists may have been absent for a complex range of reasons, sometimes personal, sometimes artistic, but there were also clear political issues at stake. The US State Department exercised a hidden but vice-like grip on the choice of US participants: no US delegates to Dakar were to drag politics into the cultural sphere by talking about civil rights and the scourge of American racism.19 Simultaneously, on the other side of the political spectrum, there was a perception among more radical black figures, such as Belafonte, that Senghor’s Senegal was a politically conservative regime that should be shunned in favour of more revolutionary states such as Sekou Touré’s Guinea.

As the festival historians Dominique Malaquais and Cédric Vincent have demonstrated, it is now evident that the US delegation had in part been funded by the CIA, who wanted to use the festival to promote a positive image of the United States in Africa.20 Many of those within and around the US delegation were conscious of a CIA presence in Dakar, although it seems that such fears were publicly silenced to preserve a sense of unity. Several years later, however, as black politics on both sides of the Atlantic became more radicalised, Hoyt Fuller would denounce the 1966 festival, and in particular the US delegation, for allowing itself to fall foul of the US State Department’s Cold War machinations: ‘One of these days, the full awful story of the American secret service’s role in the First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar in 1966 will be told, stripping of honor certain esteemed Black Americans who lent their prestige to the effort to hold to the barest minimum the political impact of that unprecedented event.’21 As well as its accusations of duplicity, the implication of Fuller’s critique was that Négritude was so devoid of radicalism that it could be safely backed by the State Department, lacking as it did any potential threat to the US’s global and domestic status quo.

It is thus evident that the Dakar festival was not the straightforward celebration of Négritude that the official discourse would lead one to believe. In the decades immediately following the event, it was habitually referred to only in passing in biographies of Senghor, albeit in glowing terms as the high water mark of Négritude. However, beyond the enumeration of its main participants and the use of quotations from Senghor’s key speeches at, or in advance of, the event, the festival itself was rarely the subject of in-depth analysis. It was as though the simple fact of the festival having taken place was enough to illustrate what it had meant. A striking but by no means exceptional example of this is Jacques Louis Hymans’s biography of Senghor, in which he does not discuss the Dakar festival at all in the main body of the text, but in an appendix featuring a chronology of Senghor’s career he writes ‘Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar: apotheosis of Négritude’.22

Closer investigation of the festival, however, reveals that the diversity of creative and political views was paradoxically acknowledged even within some of the official components of the event. For instance, the Marxist novelist Ousmane Sembène was awarded one of the festival’s literary prizes for his novella Le Mandat (The Money Order), an ironic critique of the failures of independence in his native Senegal (of which Senghor was president, let us not forget). The fact that the highly independently minded Césaire was one of the judges would surely have helped his case. Sembène, then just beginning to develop a parallel career as a filmmaker, also won the cinema prize for his haunting film La Noire de (Black Girl), about the powerful hold that France continued to have on the imagination of Francophone Africans. Sembène was an arch-enemy of Senghor, both politically and culturally: he was a virulent opponent of Négritude, which he viewed as an obfuscating, essentialist discourse that had no answers for a contemporary Africa emerging from the trauma of colonial rule. Indeed, the 1966 festival only appears in retrospect to have been a unanimous celebration of Négritude, whereas in fact a conscious process of recuperation by Senghor’s ‘fellow travellers’ within the broad Négritude movement had been required to attempt to defuse the critiques of the likes of Sembène and fellow writer Wole Soyinka. This was evident in the coverage in the Francophone West African cultural magazine Bingo, which sought to ignore the content of Sembène’s works and cast his success as proof of a newfound respect for Négritude.23

If Sembène was such a vocal opponent of Senghor, why did he take part in the festival at all? This was a pattern that would be repeated at each of the pan-African festivals of the 1960s and 1970s: some artists would opt to boycott these events, while others would choose to participate despite their differences with the host regime. In 1966 even those doubtful about the value of Négritude, such as Sembène, Soyinka and Langston Hughes, were willing to attend because of the historic cultural and political possibilities opened up by the simple fact of being there. This left them open to processes of recuperation – their very involvement in the event was cast as support for Négritude – but they thought it worth the risk so that they too could play their part in a global dialogue about the black world.

The First Pan-African Cultural Festival, Algiers, 1969

In many ways the 1966 event in Dakar set the template for the pan-African festivals that followed: from the wide range of arts included, to the tensions between ‘modern’ and ‘traditional’ art forms, to the creation of networks linking Africa with its diaspora, to heavy investment in infrastructure and buildings that later went unused or were adapted for more prosaic roles in the affairs of state, as their original artistic function came to be seen as an expendable luxury.24 However, despite these continuities, each of the festivals that followed would seek to define itself as distinctive from Dakar as the foundational pan-African cultural event.

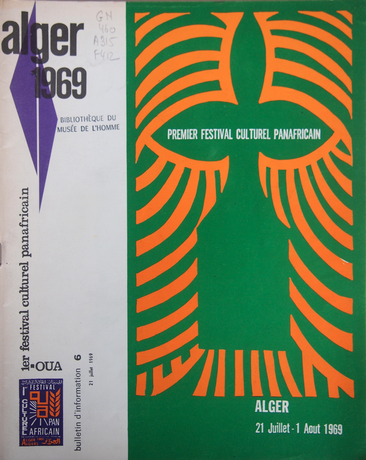

Fig.10

Brochure for the First Pan-African Cultural Festival, Algiers, 1969

PANAFEST Archive, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris

Fig.11

Jazz musician Archie Shepp performing at the First Pan-African Cultural Festival, Algiers, 1969

PANAFEST Archive, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris

Photo © Luc-Daniel Dupire

The First Pan-African Cultural Festival, known as PANAF, took place from 21 July to 1 August 1969 (fig.10). It began with a parade by members of the different delegations through downtown Algiers that was attended by thousands of ordinary Algerians. As in Dakar, a central colloquium accompanied the festival and sought through its deliberations to express a shared vision of pan-African culture. Popular music also featured centrally in the programme, with nightly concerts by the likes of Miriam Makeba and Archie Shepp (fig.11). In his celebrated documentary film on the festival, American photographer William Klein famously captured Shepp’s impromptu jazz improvisations with Touareg musicians, which gained symbolic power as an emblematic example of pan-African artistic collaboration.25 In addition, there were theatre, visual arts, literary and film programmes, with the latter including works by Sembène and Youssef Chahine.

PANAF is held up by many critics and participants as the radical response to the earlier festival in Dakar – as the type of event of which the radicals absent in 1966 would have approved. Mandated by the Organisation of African Unity, Algeria loudly proclaimed its desire to host a more inclusive event than Senegal had done. As indicated above, Senghor’s vision of pan-African culture in 1966 had been racially defined and delimited, which meant that North African culture and participants were largely omitted. Senghor also chose to exclude representatives of the liberation movements that were at that time still fighting against racist colonial regimes in the settler colonies of Southern Africa, as well as in Lusophone Africa. Only nation states were invited to send delegations to Dakar and these colonies had yet to achieve independence; Senghor’s critics perceived this as proof of his desire to keep culture and politics separate and to appease the former European colonial powers. At PANAF both of these omissions were ‘rectified’ as the organisers explicitly sought to involve the entire continent in the event, including representatives from various liberation movements in Africa, as well as the Black Panthers from the United States, and even the Palestinian Liberation Organization, thereby explicitly linking pan-African culture with an ongoing global process of political liberation from Western rule.

At the festival colloquium Négritude came under sustained attack from the representatives of various national delegations. In his analysis of PANAF, the historian Samuel D. Anderson has argued:

As the records of the symposium make clear, by that time Négritude had lost its power as a guiding ideology. Some of its critics went so far as to declare it ‘dead’. In its stead, the festival’s participants, especially those from Francophone countries, articulated a new vision of Africanity as radical cultural practice rooted in Frantz Fanon’s interpretation of the role of African intellectuals and artists in the anti-colonial struggle. The Pan-African Cultural Manifesto issued at the end of the festival was the outcome of this discussion, and in it, African cultural leaders sought to lead their continent to a radical postcolonial future.26

Many theorists of decolonisation – not least Fanon, Césaire and Amílcar Cabral – devoted a great deal of thought to the nature of the culture that should emerge from the debris of empire. Should a decolonised world look to its past or, as Fanon believed, had empire destroyed pre-colonial cultures, thus providing a blank canvas on which to develop a new postcolonial culture?27 The pan-African festivals of the 1960s and 1970s gave tangible form to these theoretical debates, and the Algiers colloquium self-consciously performed a radical vision of pan-Africanism as a force that would help to create a new, more egalitarian global order. Furthermore, in place of the racial vision of Négritude, a continent-wide vision of Africa, including its North African population, was promoted.

PANAF was certainly more overt in its support for the radical politics of the day and was ideologically aligned with radical left-wing decolonial movements. By the late 1960s, Algiers had become something of a mecca for anti-colonial radical movements inspired by Algeria’s successful struggle against the French: at the time of the festival, it could proclaim itself to be the Capital of the Third World.28 It is my contention, however, that this cannot be taken as proof that its vision of culture was fundamentally different to that expressed in Dakar three years earlier. The underlying similarities in the cultural vision promoted in Dakar and Algiers are evident in the opening speech of the latter festival, where President Houari Boumedienne (a military colonel not generally associated with cultural activities) asked: ‘What meaning, what role, what function should we give to culture, education and the arts, if they do not serve to make life better for all of our newly liberated peoples … if they do not participate in the universal task of rehabilitating man through his own actions’.29 There is more of a socialist flavour to the wording than in Senghor’s opening speech at the Dakar festival in 1966, but there is also a fundamental continuity with the thinking of Senghor (who was in fact quoted throughout the official Algiers festival book) in terms of the role that culture should play in creating a new, universal civilisation.

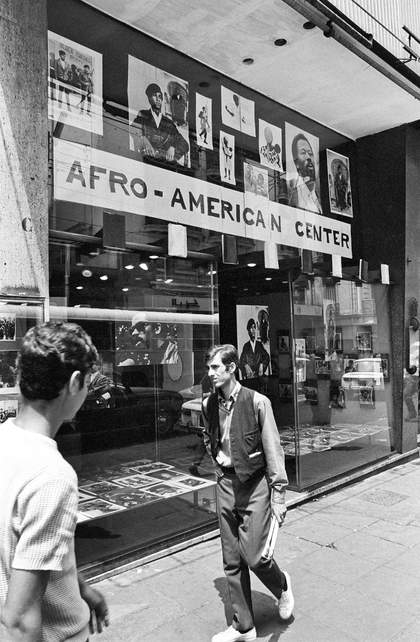

Fig.12

Robert Wade

The Afro-American Center at the First Pan-African Cultural Festival, Algiers, 1969

Photo © Robert Wade

Fig.13

Robert Wade

Eldridge Cleaver (lower left) at the Afro-American Center, Algiers, 1969

Photo © Robert Wade

The case of the Black Panthers in Algiers is instructive in thinking through both the significance and the limitations of the distinctive forms of black/African citizenship that were emerging through these festivals, forms that were based on inclusive rights of political recognition that took precedence over the sovereign authority of western nation states.30 This is a particularly important issue in the context of this article, as this citizenship offered the promise of tangible forms of belonging that might extend beyond the duration of the ephemeral event itself. The Algerian authorities had built a new, two-story Afro-American Center (fig.12) which was stocked with Black Panther pamphlets and posters, and this was where the invited Panther delegation, in particular the Panthers’ infamous Information Minister Eldridge Cleaver, held court with the press as well as local and international visitors (fig.13). As historian Andrew Apter argues, PANAF ‘revealed the vulnerabilities of [Cleaver’s] citizenship, both at home and abroad, bringing significant political calculations into play’.31 His vulnerable citizenship at home was balanced against different ambiguities in Algeria, for, as Apter suggests, we cannot ignore ‘the ephemeral character of [his] cultural citizenship in Algeria, circumscribed in space and time by the parameters of the festival itself. The Panthers did not know if Cleaver would be allowed to remain in the country after the celebration ended and the guests went home.’32 If Cleaver’s black (cultural) citizenship was activated throughout the festival, would his political welcome extend afterwards? As we have seen, Algeria was keen to proclaim itself the Capital of the Third World, but it was also a dictatorial, military regime that tolerated little dissent at home and soon grew indifferent and impatient towards its radical guests, who would find themselves expelled from the country. The form of pan-African citizenship that the festival appeared to promise would prove all too ephemeral.

Second World Festival of Black Arts and Culture (FESTAC), Lagos, 1977

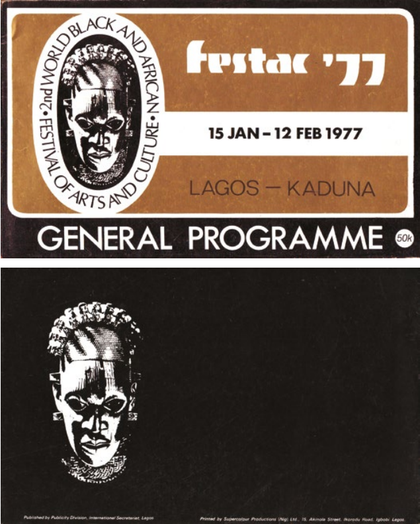

Fig.14

Front and back covers of the general programme for the Second World Festival of Black Arts and Culture, Lagos, 1977

Centre for Black and African Arts and Civilisation, Lagos

Photo © Chimurenga

Fig.15

Postcard showing the National Theatre in Lagos, constructed for the Second World Festival of Black Arts and Culture, 1977

PANAFEST Archive, Musée du Quai Branly, Paris

The First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar had clearly announced its pioneering status in its title, but it also implied that its aim was to inaugurate a regular gathering to celebrate black arts and culture. Its second edition, the Second World Festival of Black Arts and Culture (FESTAC), finally took place in Lagos in 1977 (fig.14), and there was close collaboration with Senegalese representatives on the organising committee. Chief among these was Alioune Diop, the celebrated founder of the Présence Africaine journal and publishing house in Paris, who had been the main organiser of the 1966 festival. FESTAC took place over almost a month, from 15 January to 12 February 1977. A housing estate known as FESTAC village was built to accommodate the expected 17,000 participants, and a state-of-the-art, multipurpose theatre was also constructed to house the festival colloquium, which was held over the first two weeks and had 700 participants (fig.15). The theatre hosted plays, exhibitions and concerts in its two halls, its 5,000-capacity performance venue, a massive conference room with 1,600 seats, and two cinemas. As in Algiers, popular music was a major part of the programme, with concerts by international figures such as Stevie Wonder and Gilberto Gil as well as celebrated African-based bands, including the Guinean Bembeya Jazz National and Franco from Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo).

In his 2005 book The Pan-African Nation: Oil and the Spectacle of Culture in Nigeria, Andrew Apter explores how the postcolonial Nigerian state, flush with oil revenues, attempted to use FESTAC to project a pan-African culture that was truly global but that simultaneously positioned Nigeria at its centre: ‘Nigeria’s black and African world was clearly an imagined community, national in idiom yet Pan-African in proportion, with a racialized sense of shared history, blood and culture’.33 As with the earlier festivals in Dakar and Algiers, the aim of FESTAC was to promote a vision of pan-Africanism while also gilding the status of the organising nation state.

Despite its status as a successor to the earlier Dakar festival, the Lagos edition emerged more in a spirit of rupture than continuity with the cultural agenda promoted by Senghor eleven years earlier. As we have seen, hostility towards Négritude had already been expressed, largely from a Marxist perspective, by many in Algiers in 1969. In Lagos this hostility took a somewhat different form and was based on a desire for the festival to provide a platform for all of Africa, as well as a more widely understood ‘black world’, which included ‘dark-skinned’ nations such as Papua New Guinea. At FESTAC, what had begun as a close alliance between Senegal and Nigeria soon became an acrimonious row regarding which nations should be invited to participate. Apter describes this as a ‘divisive debate over the meanings and horizons of black cultural citizenship. At issue were competing Afrocentric frameworks that clashed over the North African or “Arab” question.’34 Should North Africans fully participate, as then Nigerian military ruler, Lieutenant-General Olusegun Obasanjo, maintained, or should they merely observe as second-class citizens, as Senghor resolutely insisted? Senghor’s repeated claims that North African participation should be limited, as it had at Dakar, was seen as divisive and discriminatory at FESTAC; as Apter has noted, this view ‘ironically reproduc[ed] the very form of disenfranchisement that Senghor and his black confrères experienced in interwar Paris’.35 As the discussions of the organising committee in Lagos grew more rancorous, Alioune Diop, who was there to represent continuity with the First World Festival, found himself unceremoniously removed from his role on the committee.

If we place the struggle over North Africa at FESTAC within a genealogy of postcolonial Afrocentric festivals, it is clear that, as Apter states, ‘the political stakes of black cultural citizenship were neither trivial nor ephemeral, but emerged within a transnational festival field of cultural spectacle, racial politics and symbolic capital accumulation’.36 Indeed, the extent to which FESTAC displayed all the paraphernalia of an imagined pan-African nation was striking: it had its own emblem, flag, stamps, secretariat and identity cards for registered participants which also served as passports for entry into FESTAC Village. FESTAC consciously broke with Négritude and its focus on a ‘Negro-African’ identity associated with the sub-Saharan region, in order to develop a new definition of black cultural citizenship within a newly imagined black world order. Attending FESTAC did not just mean attending a cultural event or seeking out entertainment: it offered the chance for one to claim citizenship within the pan-African nationality that the festival was seeking to bring into being. The black communities – whether national or diasporic – as well as the liberation movements still struggling for independence were offered a black cultural citizenship during FESTAC which was deemed, within the festival’s official discourse at least, to be more significant than national citizenship.

Like Algeria’s promotion of a transnational, Third Worldist citizenship at PANAF in 1969, FESTAC’s celebration of black cultural citizenship remained largely theoretical, and it was both deeply flawed and heavily circumscribed: in the mid-1970s, Nigeria was a military dictatorship more interested in limiting than extending rights to citizens. As Apter has argued, however, this does not mean that we should dismiss the type of experimentation witnessed at FESTAC: ‘Black cultural citizenship within Afrocentric festivals is not a simulacrum of an external reality, but occupies a place within that reality – not only of recognized rights and duties, but also of violence and utopian possibilities.’37 The creation of a pan-African citizenship may ultimately have been a failed experiment, but that failure should not provide a pretext for diminishing its significance.

From Pan-Africanism to pan-Africanism

The 1960s and 1970s constituted a period when the destinies of Africa and black America seemed intertwined, a belief shared across very different shades of political opinion. For instance, in his Journey to Africa, a collection of writings on various trips to the continent, Hoyt Fuller was inspired by a 1959 visit to Guinea to declare: ‘The African emergence is a significant development for all the world, but it has a very special importance for those of African blood who are rooted in the American culture. For, with all respect to the moral intent of desegregation, only Africa will set the Black American free.’38 Such vaunted hopes that Africa might play a major part in the progress of black America, just like Nkrumah’s dream of a United States of Africa, may sound excessively utopian. Even Fuller, by 1971, was writing despondently that: ‘The reality of Africa can be enough to drive a Black man to despair, if that man believes that genuine freedom for Black people all over the world will only come when the Black African holds genuine power’.39

Pan-African political unity may seem a distant prospect today but that does not mean that attempts to achieve unity or to imagine a transnational black culture are somehow misguided. One of the main aims of much recent research on the festivals of the 1960s and 1970s is precisely to try to understand better the cultural and political energy of the pan-Africanism of this period by fostering an analysis that is not bound by considerations of the movement’s apparent ‘success’ or ‘failure’. As cultural historian Tsitsi Jaji has argued: ‘The recognition that practicing solidarity is hard work offers us an opportunity to consider pan-Africanism not so much as a movement that has or has not succeeded, but as a continuum of achievements and apparent failures that can only be understood in toto.’40 In addition, Jaji’s work has provided a timely reminder of the distinction that historian George Shepperson drew in the 1960s between ‘Pan-Africanism’ and ‘pan-Africanism’:41 the former refers to the formal international gatherings and organisations of the ‘Pan-Africanist’ movement since 1900, while ‘[s]mall “p” pan-Africanism designates an eclectic set of ephemeral cultural movements and currents throughout the twentieth century ranging from popular to elite forms’.42 The 1966 Dakar festival was a Pan-Africanist event but it was also one at which the performance of pan-Africanism, in terms of personal cultural encounters and exchange, was able to flourish.

While the 1966 festival (like the 1969 and 1977 ones) was in large part driven by a national government keen to promote the officially sanctioned account of its relevance and significance, various cultural actors, performances and works of art refused to conform to the dominant ideological narrative, despite careful attempts to police festival programming. Bringing together thousands of participants and audience members in one city inevitably gave rise to a series of personal encounters the narratives of which could not be fully regulated by the Senegalese state or other supporters of Négritude who wished to promote a specific understanding of the festival. For example, Hélène Neveu Kringelbach has charted the ‘popular cosmopolitanism’ of the dance parties and street events in Dakar, while Jaji has traced non-elite accounts of the festival in popular magazines.43 In the process, both Neveu Kringelbach and Jaji recover the voices of female participants (mainly dancers) in the festival, whose stories are often occluded. Neveu Kringelbach also notes the impact on individual Senegalese dancers of witnessing the modernity of the Alvin Ailey dance troupe’s performances (see fig.4), which would influence their vision of African dance. The story of the vast pan-African festivals of the 1960s and 1970s will thus remain incomplete if it does not include the experiences of a wide range of individual actors alongside the overarching national and transnational narratives promoted by the organising nation state. To return to Shepperson’s terms, we must attempt to capture the story of pan-Africanism alongside that of Pan-Africanism.44

For Senghor, the Dakar festival was designed to act as a living ‘illustration of Négritude’,45 the moment when the theory that he had written about at such great length would come alive. The examples above demonstrate, however, that this living illustration, this performance of Pan-Africanism, did not result in a monolithic assertion of Négritude as a unifying black identity. The Dakar festival, like those in Algiers and Lagos, was an occasion to question, challenge, debate and explore rather than simply to assert or passively accept various conceptions of global African culture, identity and forms of belonging. There was no consensus about what Pan-Africanism meant or what role culture should play in the period after empire: rather, the festival was a site in which various actors could come together to perform their own understanding of African culture and identity in complex and often contradictory ways.