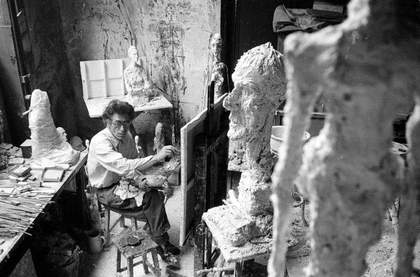

Alberto Giacometti modelling a bust in his studio in Stampa, Switzerland in 1965, photographed by Ernst Scheidegger

© Alberto Giacometti estate/ACS+DACS in the UK, photo © 2017 Stiftung Ernst Scheidegger-Archiv, Zürich

Slowly, as the 20th century began, writers and painters became acutely aware that writing is made with language, painting with paint and sculpture with material. Artists also became deeply alert to ideas about consciousness, symbols and will – ideas that made their way into the public domain courtesy of Freud, Jung, Nietzsche and their followers. Thus, a sentence, a brushstroke, or a way of moulding plaster had its own dynamic power: it was an act of will, but also an act of guile that managed to conceal as much as it revealed.

A movement of the hand, therefore, could be both absolutely pure and oddly uncertain. It could be done for its own sake, and also carry a symbolic or resonant force. The artist allowed revelation to come hand-in-glove with concealment. In work made, the nervous system and the shivering grammar of the hidden self emerged as much as did the decisive image or the deliberate form.

What more could painting and sculpture mean, or do, as Alberto Giacometti, who was born in 1901, began to work? What could the statue, the bust, the pictorial surface, or indeed the lithograph look like if it had to seem both knowing and pure, and also be refracted in the viscous, complex and uneasy waters of the symbol and the self? These problems preoccupied him as he attempted to create new forms and systems, as he tried to formulate a personal iconography.

Giacometti was an artist both rooted in the exact and transported by the visionary. He was both a maker and a seer, both a craftsman and an alchemist. He was interested in the deepest and most precise contours of the face, but had no interest in making mere representations of those who sat for him. His drawings, which are exquisite, do not read like preparations for his sculpture or his paintings; it was as though everything he touched he sought to perfect, knowing all the time that he would fall short.

Giacometti's Walking Man I 1960 photographed by Ernst Scheidegger in the Swiss countryside, 1963

© Alberto Giacometti estate/ACS+DACS in the UK, photo © 2017 Stiftung Ernst Scheidegger-Archiv, Zürich

Giacometti's The Chariot 1950 photographed by Ernst Scheidegger in the Swiss countryside, 1963

© Alberto Giacometti estate/ACS+DACS in the UK, photo © 2017 Stiftung Ernst Scheidegger-Archiv, Zürich

His sculpture bears all the signs of being shaped and lovingly worked on, then sent to the foundry with a sigh of resignation. He managed to make images that seem strangely perfect, alive and organic, but also filled with a sense that much unease and uncertainty went into their making. Thus, the plaster models have signs of both the artist’s nerves and his deep intent, his controlling and fearful eye. Since what he made was all process, all released energy, quick decision and sleight-of-hand, then these models were not merely preparations for some final perfection, but moments when the raw will was subtly apparent but not loudly on display. The image was what was on display; everything led towards the image.

Giacometti’s sculpture was made using what seemed like the minimum of means. He was alert to the power of the signs of all the untidiness and moment of random decision that went into the making of the plaster models. He was aware too of the power that the finished bronze would have against the living light all around it, as the solidity of the image both filling the air and resisting it.

He was interested in the rawness and the immediacy of reality rather than offering some smooth interpretation of the visible or emotional world. He was also concerned to create, as he worked, illusions of monumentality. Even if the scale was, or seemed to be, small, he was not a minimalist; he did not seek to lower the tension or the ambition in the work he made out of humility.

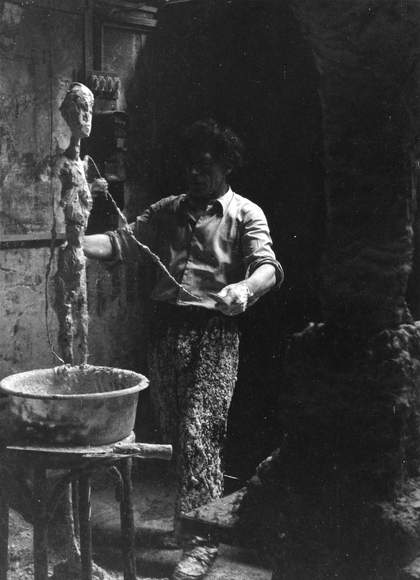

Giacometti working with plaster in his Paris studio in 1959, photographed by Isaku Yanaihara

© Alberto Giacometti estate/ACS+DACS in the UK, photo © reserved

Giacometti found a style in sculpture and stuck to it. He made skinny and elongated, attenuated figures, working a great deal with his wife Annette as a model, as well as his mother and brother Diego, who was also an artist. His figures are capable of a presence that is almost philosophical, or at least they have some sense in their aura that they represent the human dilemma, human frailty, human pride. In them, with great tactile care and almost by implication, he managed to capture a sense of the human fate in the world as not only tragic but maybe wondrous too.

To create this aura, Giacometti managed to make the space around the thin piece of bronze appear to circle it and enclose it, the very air becoming unsettled by the mass that had been generated. He set about disturbing the context, the gathered light, around his work, all the more to make the work seem a place where something significant had occurred or been dramatised. A site where something had been deeply felt and then painstakingly realised by a sort of exquisite shaping.

This is pointed and obvious also in his drawings and prints. He knew when to leave space alone; he was conscious of the moment when a single line or mark could do enough to evoke both itself and the emptiness around it and also represent, however tactfully and ironically, the known world.

Thus, the dance between light and mass, or between hard presence and impalpable absence, or between what had been touched and gazed upon and retouched and moulded and what had been left to chance, could hit the nervous system of the viewer, become all stark undercurrent or be like an echo that has more force than the original sound.

Alberto Giacometti, Head of Man, Face On c.1956–7, oil paint on canvas, 26.1 x 21.6cm

© Alberto Giacometti estate/ACS+DACS in the UK

Giacometti was a great modern artist partly because of his ability to create a strange and self-conscious iconography of the body. His figures are filled with iconic dignity, a stillness, a solitariness, a sense of a dense inner life, almost a spiritual life. He suggested that our presence in the world is a set of fluent, fluid gestures, but he took care to imply, as Beckett did, that these gestures took place in the small time between the cradle and the grave. All presence in his work, while fully vivid, has its own stoical descent towards nothingness written into its shape, its stance.

In his drawings and paintings he knew how to draw a face while making the viewer utterly alert once more to the space around the head and to the lines and marks in that space. He had enough skill to make you believe that the face he made was alive and real; he had enough irony to make you see that he was merely manipulating his material.

Standing Woman 1948 and other sculptures in Giacometti's Paris studio, c.1948–9, photographed by Ernst Scheidegger

© Alberto Giacometti estate/ACS+DACS in the UK, photo © 2017 Stiftung Ernst Scheidegger-Archiv, Zürich

Giacometti arrived in Paris to study in 1922. He got to know, over the following decades, a great number of the leading artists and writers in the city, including many surrealists. Some of his early sculpture, such as Suspended Ball from 1930–1 or Woman with Her Throat Cut from 1932, is as good as surrealism gets. He had his first show in Paris in 1932 and was, three years later, officially expelled by the surrealists – a badge of honour – for betraying the cause of the deep unconscious by working from life, although a decade later he began once more to work from imagination.

His art has been cleansed of so much that it is important to remember that it has been cleansed also of the easy surrealist release of meaning. He sought, instead, to move closer to the image itself, to the face, the head, the space around them, the material, in all their austere imperfections and strange, coiled energy. He was interested in form in all its freedom and mystery as much as he was interested in expression or self-expression.

Giacometti did not arrive quickly or easily at what became his signature style. And even when he did, each object he made had a real sense of newness and struggle about it. All his life he was fascinated and also repelled by the relative and ambiguous nature of space, how something large, for example, could seem small if you looked at it, or thought about it, for long enough.

In the early 1940s many of his figures were tiny, but in the 1950s, after much effort on his part, they became taller. He needed very little to inspire him. ‘One tree,’ he said, ‘is enough for me; the thought of seeing two is frightening.’

Giacometti in his Paris studio working on a project for Chase Manhattan Plaza in 1958, photographed by Ernst Scheidegger

© Alberto Giacometti estate/ACS+DACS in the UK, photo © 2017 Stiftung Ernst Scheidegger-Archiv, Zürich

Giacometti working on Four Figurines on a Base 1950–65 and Figurines of London II 1965 in the basement of the Tate Gallery hours before the opening of his retrospective in 1965, photographed by Pierre Matisse

© Alberto Giacometti estate/ACS+DACS in the UK, photo © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2017

David Sylvester in his book Looking at Giacometti reported on how the artist worked when he made sculptures from memory. He would build up and then cut back to scratch, build again, working fast, demolishing completely, then go at it again. But there would be no enormous change in the image created each time. He wanted to be able to get the image right in an instant, in a flash. Most of the time he needed many such flashes before he would let the piece go. As an artist, he had a natural facility that he fought against and distrusted, seeing what he could do to make it harder for himself, as he made it more fascinating and complete for the viewer, more filled with mystery of the great gap or the great connection between what the hands of the sculptor can do and what the material will yield.

Colm Tóibín is a writer who lives and works in Dublin. His latest novel, House of Names, is published by Simon & Schuster.

Giacometti, The Eyal Ofer Galleries, Tate Modern, supported by Maryam and Edward Eisler, with additional support from the Alberto Giacometti Supporters Circle, Tate Patrons, Tate Americas Foundation and Tate Members, 10 May – 10 September. Curated by Frances Morris, Director, Tate Modern, and Catherine Grenier, Director, Chief Curator, Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris, with Lena Fritsch, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern, assisted by Mathilde Lecuyer, Associate Curator, Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti.

Colm Tóibín is a writer who lives and works in Dublin. His latest novel, House of Names, is published by Simon & Schuster.