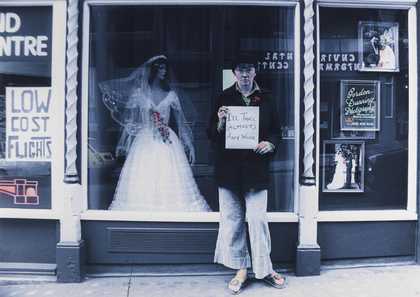

Jo Spence, with Terry Dennett

The Highest Product of Capitalism (after John Heartfield) (1979)

Tate

Over 100 years have passed since the Representation of the People Act of 1918 gave some women in Britain the right to vote. Inspired by this landmark moment in the journey towards female equality, our online tour looks at some of the artists who have resisted traditional expectations of what women can and should do.

Mary Beale

Mary Beale

Portrait of a Young Girl (c.1681)

Tate

Mary Beale is often credited as Britain’s first professional female artist. Unusually for the time, she was the breadwinner of her family. From the 1650s onwards, she earned roughly two hundred pounds a year through her paintings.

She was seen as an authoritative figure on art and respected by many of her male peers. Though never published, her text Observations is also thought to be the first instruction book written by a female painter.

We know a lot about her life and paintings through the notebooks of her husband Charles. In a refreshing reversal of typical gender roles, he acted as her studio assistant. Charles primed her canvases, mixed the pigments and handled the accounts. Writing about women’s relationships with men, Beale declared that a woman should be a 'wife and a friend, but not a slave.'

Friends and family members were the most common subjects for her paintings. These two portraits show her son Bartholomew, who also acted as her studio assistant.

Emily Mary Osborn

Emily Mary Osborn

Nameless and Friendless. “The rich man’s wealth is his strong city, etc.” - Proverbs, x, 15 (1857)

Tate

Nameless and Friendless is as bleak a painting as its title suggests. A young orphaned woman offers one of her paintings to a dealer. She seems resigned, as if she knows already that his answer will be a ‘no’. The other men in the room are either sneering or leering at her, while her mud-splattered skirt and downcast expression suggest a desperate situation. The subtitle of the painting, taken from the Book of Proverbs, emphasises the often powerless situation of single women in the city.

Osborn was a successful painter, even counting Queen Victoria as a patron. She used this position of power to help improve the lives of the kinds of women typically depicted in her genre paintings. She was a member of the Society of Female Artists, established in 1857 to help women overcome the difficulties in exhibiting and selling their work. Elsewhere, she was a dedicated campaigner for women’s rights. She put her name to the 1859 petition demanding women’s access to the Royal Academy Schools, as well as to the 1889 Declaration in Favour of Woman’s Suffrage.

This is Nameless and Friendless by Emily Mary Osborn.

Painted in 1857, it was intended as a political statement about women’s rights.

Emily Mary Osborn was one of the most important artists associated with the campaign for women’s rights in the nineteenth century.

In Nameless and Friendless, Osborn shows us the situation of a single woman in Victorian England.

The central character is a female artist in a vulnerable situation.

Female artists were uncommon in Victorian times. Her black dress suggests that she is mourning someone and is likely to be supporting herself alone.

Outside it’s raining and her mud-splattered skirt and dripping umbrella tell us she has travelled through terrible conditions to get here.

Accompanied by a boy, possibly her brother, she offers her paintings to an art dealer.

Her downcast face and his curious expression suggest rejection.

A young man on a ladder looks down on her painting, while across the room, two older men gaze at the artist.

Isolated in the centre of the composition between leering and disrespectful glances, the artist looks downwards and nervously pulls at the knotted string that once bound her picture.

When first shown at the Royal Academy in London in 1857, Osborn included a quote from the Bible in the title of the panting: ‘The rich man’s wealth is his strong city.’

In Victorian England, the city and the outside world were considered the place of men, with women’s roles restricted to indoor and domestic environments.

In Nameless and Friendless, Osborn presents us with common models of femininity that existed in Victorian society, but also offers an alternative.

In the corner, the men leering at the artist are holding a picture of a ballerina, a working female figure that was commonly objectified and sexualised by conservative Victorians.

Leaving the shop with her son is a middle-class woman, representing a domestic female figure; a wife and mother who is secure as part of a family, but whose face is invisible.

Our protagonist, however, represents a third choice: a single woman trying to earn a living on her own in a trade traditionally occupied by men. However, in this hostile environment, she becomes nameless and friendless.

Emily Mary Osborn was actively involved in the campaign for women’s rights that gathered momentum in the mid-19th century.

She was a member of the Society of Female Artists, established in 1857 to help overcome the difficulties experienced by female artists exhibiting and selling their work.

In 1859 Osborn signed a petition to the Royal Academy of Arts to open its schools to female students, which it did a year later in 1860.

And in 1889 she campaigned for the Declaration in Favour of Woman’s Suffrage.

Osborn’s own career was far removed from the woman in Nameless and Friendless.

The daughter of a priest, she was encouraged to be an artist by her family and was supported by wealthy patrons including Queen Victoria.

However, she used this position of power to help improve the lives of the women depicted in her paintings.

Gwen John

I cannot imagine why my vision will have some value in the world... and yet I know it will

Gwen John trained at the Slade School of Art in London, which at the beginning of the twentieth century was the only art school in Britain that allowed women to study. In a career still dominated by men, John had to struggle for recognition. Her quietly powerful, intimist portraits stand at defiant odds with the work of her peers (including her brother, Augustus). She worked in solitude and kept faith in her own talents. Commenting on an exhibition of Cézanne watercolours, for example, she said, ‘These are very good, but I prefer my own.’

John was part of a group of ‘Bohemians’, artists and intellectuals who lived experimental life-styles. In around 1902 she and her friend Dorelia McNeill travelled around France on foot, sleeping rough and earning a little from sketching and singing. John’s friendship with McNeill was one of the many strong female relationships that punctuated the painter’s life. These women were her sitters, fellow artists and perhaps even her lovers.

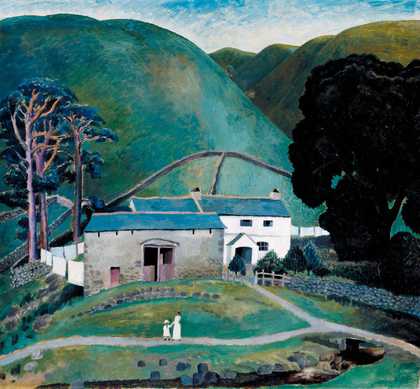

Dora Carrington

Dora Carrington

Farm at Watendlath (1921)

Tate

Dora Carrington is most well-known for her association with the Bloomsbury Group, a collective of bohemian artists, writers and thinkers. Carrington graduated from the Slade School of Art in 1910 where she won a scholarship. Having studied alongside artists like Paul Nash and Dorothy Brett, Carrington was in good company with the forward-thinking minds of the early twentieth century.

Carrington often challenged the standardised ideas around womanhood. She prefered to be known simply by her surname. She wore her hair cropped and her fashion was always deliberately androgynous. She was known to have had sexual relationships with both men and women, her longest relationship being with homosexual writer Lytton Strachey. After his death in 1932, Carrington committed suicide.

Society’s definitions of the female and the feminine troubled Carrington. She found power in rejecting its prescribed ideas. In Farm at Watendlath, critics have pointed out how Carrington manipulates the gradients of the hilly landscape to emulate the curves of the female body. She paints two female figures, one young and one older. It has been suggested these represent Carrington at different stages of her life. Their positioning in the painting shows them being overwhelmed by the landscape, as Carrington was by the rigid notions of womanhood.

Evelyn Dunbar

Evelyn Dunbar was the only female British Official War Artist to receive a salary during the Second World War. In 1940, she was commissioned to record the Women's Land Army at work.

The Land Army was re-established in 1939 to provide a new rural workforce, as most of the jobs were left unoccupied by men heading to the Front. Her paintings provide an unsentimental and detailed picture of the kinds of work undertaken by women during this period. A Land Girl and the Bail Bull shows one of those girls working with a dairy herd in the Hampshire Downs. She is about to catch and tether the bull – ‘a delicate and dangerous job’, according to Dunbar.

Despite the importance of their roles, women were paid less than men for doing the same work. After the war, when men reclaimed their previous roles, women were encouraged to return to domestic duties. Even so, organisations like the Land Army helped pave the way towards the increased demand for equal rights in the workplace.

Bridget Riley

Bridget Riley

Deny II (1967)

Tate

For some, being labelled a ‘woman artist’ felt patronising and restrictive. In 1973, Bridget Riley published her essay ‘The Hermaphrodite’, making her thoughts on the matter clear. Riley didn’t want to be categorised by her gender, calling it a ‘red herring’:

I have never been aware of my femininity as such, when in the studio. Nor do I believe that male artists are aware of an exclusive masculinity while they are at work.

Riley’s comments have sometimes been taken out of context and used to suggest that she is anti-feminist. Instead, Riley asserts her right to be an artist on her own terms. 'Women as artists,' she writes, 'should focus on how to start, lead and sustain a creative life. It’s not a question of style or a break with tradition.’

Jo Spence

Jo Spence, with Terry Dennett

Remodelling Photo History: Realization (1981–2)

Tate

Through playful self-portraits, Jo Spence comments on the place and power of women within the market economy. In her series Remodelling Photo History, for example, Spence parodies advertising imagery to criticise the way in which women are often objectified as home-makers, cleaners and objects of sexual pleasure.

Politics and social equality is always at the heart of her work. She was one of the founding members of the Hackney Flashers, a women’s art collective active between 1974 and 1980. The group’s title was a playful pun on the flash of the camera, their medium of choice, and their desire to bring to light situations that are normally hidden. Their group exhibitions explored the intersection between feminism and socialism. Women and Work in 1975 documented the types of roles, often unskilled and low-paid, taken on by female employees. Who’s Holding the Baby? in 1978 criticised the lack of childcare provision and the impact that this had on women’s lives.

Lubaina Himid

Lubaina Himid CBE RA

The Carrot Piece (1985)

Tate

© Lubaina Himid, courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London

In Lubaina Himid’s The Carrot Piece, a white man on a unicycle tries (and fails) to tempt a black woman with a carrot. Speaking about the work, Himid says that it was made at a time when cultural institutions ‘needed to be seen’ to be integrating people of colour into their programmes through ‘silly games and pointless offers.’ Himid suggested what was actually needed ‘to make a positive cultural contribution: self-belief, inherited wisdom, education and love.’

Himid calls herself a ‘black feminist’, and sees the two terms as inseparable. It is important to remember that much discussion of women in art fails to address the experience of people of colour. Not only does Himid tackle this bias in her artwork, she also actively works to give other black artists a voice. During the 1980s, she curated a number of exhibitions in London, including Five Black Women at the Africa Centre and Black Woman Time Now at Battersea Arts Centre.

In 2010 Lubaina Himid was appointed MBE for her ‘services to black women’s art’ and in 2017 became the first woman of colour to win the Turner Prize.