Carolyn Mims Lawrence Black Children Keep Your Spirits Free 1972 Collection & © Carolyn Mims Lawrence

Soul of a Nation celebrates the work of Black artists working in the United States in the two decades after 1963. During this turbulent time, these artists asked and answered many questions. How should an artist respond to political and cultural changes? Was there a ‘Black art’ or a ‘Black aesthetic’? Should an artist create legible images or make abstract work? Was there a choice to be made between addressing a specifically Black audience or a 'universal' one?

The exhibition looks at responses to such questions, with each room devoted to groups of artists in cities nationwide, or to different kinds of art. While showing strong communities and robust artistic dialogues, it also reveals necessary disagreements about what it meant to be a Black artist at this time.

In 1963, when the exhibition begins, the American Civil Rights Movement was at its height. At the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington D.C., Dr Martin Luther King, Jr dreamed that his children would live in:

a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.

King referred to himself proudly as ‘Negro’, but by this time, many who were on the March were beginning to call themselves Black. Taking issue with King’s non-violent position, especially after appalling racist violence later in 1963, many joined in calls for ‘Black Power’. Others rejected the idea of an integrated America, and began to speak of a separate, autonomous Black Nation. Looking at newly independent African nations, and understanding an ancestral connection to the continent, the terms ‘Afro-American’ and ‘African American’ also began to take root. The artists in Soul of a Nation were profoundly aware of these political visions and different senses of self, and each took an aesthetic position in relation to them.

Playlist

Inspired by the works and artists on display, curators Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley have put together the following playlist. Enjoy songs by artists including Nina Simone, Gil Scott-Heron, Aretha Franklin and Curtis Mayfield as you delve deeper into the themes of the exhibition.

Room one: Spiral

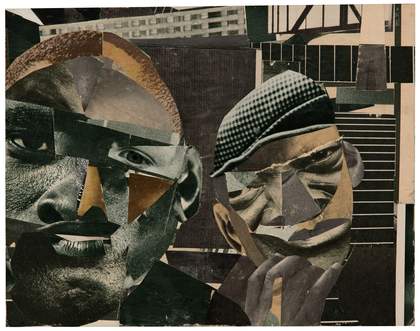

Romare Bearden Pittsburgh Memory 1964 Private Collection © Romare Bearden Foundation/DACS, London/VAGA, New York

The exhibition starts with the Spiral group that formed in New York in 1963. As they wrote:

During the summer of 1963 at a time of crucial metamorphosis just before the now historic March on Washington, a group of Negro artists met to discuss their position in American society.

Room one tracks

- Mahalia Jackson How I Got Over

- Max Roach Freedom Day

- Nina Simone I Wish I Knew How it Would Feel to be Free

- Charles Mingus Original Faubus Fables

Many of the 15 members were established artists and they worked in wide-ranging styles. While they asked the question ‘Is there a Negro image?’, they gave no single answer. They mounted one joint exhibition in 1965, agreeing to show only ‘works in black and white’. The exhibition included one of Norman Lewis’s abstract paintings, Romare Bearden’s Photostat of one of his collages, and Reginald Gammon’s forceful painting of the March. Younger Black artists would look back to Spiral later, impressed both by the group’s determination to exhibit together in an artist-run space, and by the range of artistic viewpoints of its members.

Room two: Art on the streets

Benny Andrews Did the Bear Sit Under a Tree? 1969 Emanuel Collection © Estate of Benny Andrews/DACS, London/VAGA, NY

For many Black artists in this period, a key question was: where to present their art? Their work was excluded from nearly all mainstream museums. Linked to this was another question: which viewers should they address?

Room two tracks

- Elaine Brown Seize the Time

- Gil Scott-Heron The Revolution Will Not Be Televised

- Gil Scott-Heron Brother

- Archie Shepp Attica Blues

Find out more about room two

The Ghetto itself is the Gallery for the Revolutionary Artist.

Emory Douglas

This room looks at ways artists positioned their work beyond conventional gallery and museum spaces. It reveals how they inspired and mobilised specifically Black and local audiences.

OBAC (pronounced ob-bah-see; The Organization of Black American Culture) formed in Chicago in 1967. This group of artists and writers created The Wall of Respect, an outdoor mural in the city’s South Side. The Wall featured images of ‘Black Heroes’ - civic leaders, writers, musicians, sports stars and dancers - and became a gathering place for poetry readings, music, and performances. It sparked a wave of murals in African American neighbourhoods nationwide.

In 1966 The Black Panther Party (BPP) for Self-Defense formed in Oakland, California. The ten-point party platform set out demands for improved housing and education, and an end to police brutality. Their statement began, ‘We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community’. Panthers carried guns to protect Black residents, and launched a free breakfast programme for working-class children and health clinics for locals. Soon after its founding, the BPP created The Black Panther newspaper. Young artist Emory Douglas was appointed the party’s Minister of Culture and designed the newspaper. In his backpage

illustrations, photomontages, posters and flyers, Douglas depicted the party’s demands, its leaders and recognisable scenes of both struggle and triumph.

Research on the mural movement was carried out by Julia Bailey.

ROOM THREE: FIGURING BLACK POWER

‘Black Power!’ Activist Stokely Carmichael made the rallying cry for nationwide solidarity in a speech at the Mississippi March Against Fear in 1966. It was a efusal to be cowed by acts of racist violence that sought to suppress demands for equality.

Room three tracks

- Eddie Gale Black Rhythm Happening

- Donny Hathaway Tryin' Times

- Syl Johnson Is It Because I'm Black

- James Brown Say It Loud (I'm Black And I'm Proud)

Find out more about room three

Art for me now must develop from a necessity within my people. It must answer a question, or wake somebody up, or give a shove in the right direction – our liberation.

Elizabeth Catlett

Soon, the saying was not only heard but shown in the defiant act of the raised fist: the Black Power salute. Painting and sculpture likewise became powerful vehicles for protesting against this violence and communicating the urgent message of Black liberation.

Boston-based artist Dana Chandler referred to himself as a ‘Black Expressionist’, noting:

Black art is a tremendous force for education and political development… I mean to tell it like it is. I ain’t subtle and I don’t intend to become subtle so long as America remains the great white destroyer.

In a painting which is now missing, Phillip Lindsay Mason referenced the 1965 assassination of American leader Malcolm X to make visible the life-and-death seriousness of the struggle. The older generation of artists like Elizabeth Catlett and Archibald Motley also expressed their commitment to social justice and survival.

Faith Ringgold, having been denied membership to Spiral’s group of artists, developed her own unique style she called ‘Super Realism’:

the idea was to make a statement in my art about the Civil Rights Movement and what was happening to Black people at that time, to make it superreal.

Kay Brown was part of an outspoken and pioneering group of Black women artists whose art expressed the interrelated struggles against political oppression, racial discrimination and sexism.

ROOM FOUR: LOS ANGELES ASSEMBLAGE

This room brings together work by four artists based in Los Angeles. They created art by recycling and bringing together objects in different formations, known as assemblage.

room four tracks

- The Jazz Crusaders Watts Happening

- The Watts Prophets Dem Niggers Ain't Playing

Find out more about room four

West coast Black art stands in direct opposition to art for art’s sake. It insists that if art is not for the sake of something it is not art.

Noah Purifoy

Los Angeles was a city experiencing great racial tension. In 1962, police had entered a mosque and shot dead an unarmed member of the Nation of Islam. Two years later, another instance of police violence in a predominantly African American neighbourhood triggered the Watts Rebellion, which left 34 dead, and properties and shops in ruins.

Melvin Edwards began his Lynch Fragments in 1963. He used metal machine parts as well as chains, his title referring to the history of lynching. Two years later, after the Watts Rebellion, Noah Purifoy began collecting materials from the streets, using them to create constructions. By turning former consumer items into imaginative artworks, he hoped to inspire viewers to be creative and reject materialism. John Outterbridge reflected on racial oppression in his Containment series. Later, drawing on his memories of rituals in the American South, he began his Ethnic Heritage series, small doll-like figures made with found materials.

Purifoy and Outterbridge both had exhibitions at the Black-run Brockman Gallery, one of a small number of spaces whose programmes featured Black artists. Another was Gallery 32 where Betye Saar exhibited her work. Saar made assemblages from racist material she’d gathered, scrutinising historical and present-day racism and fashioning images of proud defiance.

ROOM FIVE: AFRICOBRA IN CHICAGO

Wadsworth Jarrell Revolutionary 1972 Private Collection © Wadsworth Jarrell

How do you represent the ‘expressive awesomeness that one experiences in African art and life in the U.S.A.’? The Chicago artists’ collective AfriCOBRA – the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists - which formed in 1968, proposed an answer.

Room five tracks

- Art Ensemble of Chicago Certain Blacks (Do What They Wanna)

- Gary Bartz Uhuru Sasa

We wanted to create a greater role as Black artists who were not for self but for our kind […] Can we as AfriCOBRA artists sacrifice the wants of self and ego to create the needed positive visual images of our people? The answer was yes, we can!

Barbara Jones Hogu

Find out more about room five

AfriCOBRA came out of discussions in 1962 between Wadsworth Jarrell and Jeff Donaldson about whether a uniquely ‘Negro’ art movement could be based on a shared sensibility. Many of its members were later involved in painting the mural The Wall of Respect, seen in Room Two.

When the group started out, they began by setting themselves tasks – for instance to paint images of the Black family – meeting every week to discuss each other’s work. Soon they decided to choose their own subjects. Some created uplifting images of everyday people; Jarrell painted portraits of leaders like Malcolm X and Angela Davis whose revolutionary politics AfriCOBRA admired.

In the AfriCOBRA manifesto of 1970, Donaldson summed up their collective aesthetic, and showed how AfriCOBRA departed from American and European models of pop art, realism and abstraction. The new aesthetic was based on ‘rhythm’, ‘shine … the rich lustre of a just-washed ‘fro …’ and ‘Colour colour Colour colour that shines, colour that is free of rules and regulations’. Text would often be incorporated into pictures, anchoring messages. The artists made prints based on their most popular paintings. They wanted their work to be distributed widely and pinned proudly on their audiences’ walls.

ROOM SIX: THREE GRAPHIC ARTISTS, LOS ANGELES

This room brings together three artists based in Los Angeles in the late 1960s, who took different approaches to the graphic image.

Room six tracks

- The Last Poets When The Revolution Comes

- Sly and the Family Stone Skin I’m In

Find out more about room six

I feel it my moral obligation as a Black artist, to try to graphically document what I feel socially.

David Hammons

Charles White was a respected painter, printmaker and esteemed art college professor. David Hammons had been one of White’s drawing students. In 1968, Hammons started making body prints, coating himself in vegetable fat and pressing his body onto printing paper before applying pigment to reveal the image saturated into the surface. Los Angeles native Timothy Washington, who was also a recent art school graduate, developed a technique of etching into enamel paint applied to sheets of metal. Both Hammons and Washington had exhibited at the Brockman Gallery alongside the Los Angeles-based artists shown in Room Four.

In 1971, White, Hammons and Washington were the featured artists in the exhibition Three Graphic Artists at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Three years earlier, Claude Booker and Cecil Fergerson, two art handlers at the museum, had founded the Black Arts Council (BAC) in order to show the work of African American artists and to engage Black visitors. The BAC quickly grew to around 3,000 members. Three Graphic Artists was the first exhibition resulting from their efforts.

The exhibition was met with some resistance. Booker and Fergerson picketed the opening reception, incensed by the exhibition’s relegation to a minor gallery within the museum and to White having been denied a prominent solo exhibition. Still, the BAC persisted in advocating for subsequent shows, culminating in Two Centuries of Black American Art in 1976.

ROOM SEVEN: EAST COAST ABSTRACTION

William T. Williams Trane 1969 Studio Museum in Harlem (New York, USA) © William T. Williams; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

Based in New York and Washington D.C., the artists in this room knew each other and exhibited together several times in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Room seven tracks

- John Coltrane Quartet Africa

- Duke Ellington Fleurette Africaine (African Flower)

- Ornette Coleman Beauty is a Rare Thing

Figurative art doesn’t represent blackness any more than a non-narrative media-oriented kind of painting, like what I do.

Sam Gilliam

Find out more about room seven

Frank Bowling Texas Louise 1971 Rennie Collection (Vancouver, Canada) © Frank Bowling

During their studies in major art schools such as Yale, they had become aware of the innovations in abstract painting on the East Coast after the generation of abstract expressionists that included Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. They were interested in recent innovations in abstract art, such as hard-edged painting and staining the canvas, as well as using unusually-shaped canvases instead of rectangles and squares.

In addition, they were profoundly concerned with what it meant to be Black. Although they did not make figurative images, their personal experiences and interests came into their art in different ways. For some, this meant making abstract homages to assassinated political leaders such as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr; for others, it meant connecting their compositions and processes to the radical improvisatory jazz of musicians such as John Coltrane. Jack Whitten used an Afro-comb instead of a paintbrush – an implement connected with then-current Black hairstyles.

However, many artists in this room encountered severe criticism from other Black artists and critics, who felt that abstract painting could not connect to the lives of Black Americans. A strong argument in favour of the work shown here was provided by Frank Bowling, who was born in British Guiana and studied in London, before coming to New York in 1966. He got to know many of the artists and included several in an exhibition he organised in 1969 called 5+1. In his series of essays on ‘Black art’, he argued that artists such as William T. Williams and Jack Whitten were able to ‘re-route fashion and current art convention to ‘signify’ something different’ to Black viewers than to white ones.

Room eight: Black Light

Roy DeCarava was one of the first Black photographers to establish a successful career as an independent artist rather than as a photojournalist or studio portraitist.

Room eight tracks

- John Coltrane Alabama

- Charles Mingus Better Get Hit in Your Soul

- Charles Mingus Goodbye, Porkpie Hat

Find out more about room eight

You should be able to look at me and see my work. You should be able to look at my work and see me.

Roy DeCarava

DeCarava studied painting and drawing under Charles White (whose work is in Room Six) in the 1940s, but soon concentrated on photography. He collaborated with the poet Langston Hughes on The Sweet Flypaper of Life in the mid-1950s, creating touching pictures of family life in Harlem, and by the early 1960s was recognised by younger Black artists as the outstanding figure working in the medium.

DeCarava printed all his images himself, often using very dark blacks and greys, knowing viewers would need to slow down to look closely at his works. For many, his extraordinary handling of a dark tonal range amounted to a Black aesthetic in photography, as did his choice of subject matter. DeCarava sometimes photographed leaders associated with the Civil Rights Movement, but he was equally drawn to jazz musicians and to everyday people in the New York neighbourhoods of Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant. His abstract photography and architectural studies were just as important to him.

Kamoinge

DeCarava was the first director of the Kamoinge Workshop, a group of Black photographers who came together in the summer of 1963. The works on the wall opposite DeCarava’s photographs are by members of this group. ‘Kamoinge’ is a word from Kenya’s Kikuyu language meaning ‘a group of people acting together’. The group functioned as a discussion forum and its members showed their work together without ever putting forward a singular model for Black photography.

Several members were also highly involved with The Black Photographers Annual, published four times from 1973 until 1980, becoming the most useful platform for Black photographers at this time. The Annual was a publication where everyday Black life was represented in all its fullness, without an emphasis on deprivation and activism – the subjects of so much documentary photography in illustrated magazines of the time.

Room nine: Black heroes

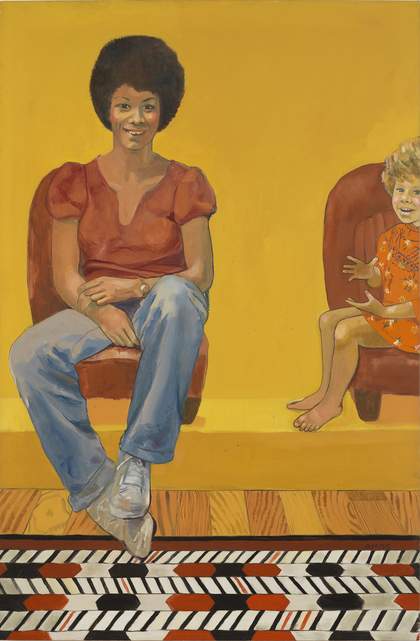

Emma Amos Eva the Babysitter 1973 Courtesy of Emma Amos, the Amos family, and RYAN LEE Gallery

In this period many artists – both Black and white - created powerful images of famous Black Americans. This room brings together portraits of boxers, writers, and painters, such as Andy Warhol’s portrait of Muhammad Ali, Bob Thompson’s painting of the writer LeRoi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka), and Alice Neel’s portrait of Faith Ringgold.

Room nine tracks

- Curtis Mayfield Miss Black America

- Billy Paul Am I Black Enough for you?

- Roy Ayers Red, Black & Green

- Aretha Franklin Young, Gifted and Black

- Stevie Wonder Black Man

- Marvin Gaye What's Going On

- Bobby Hutcherson Black Heroes

Find out more about room nine

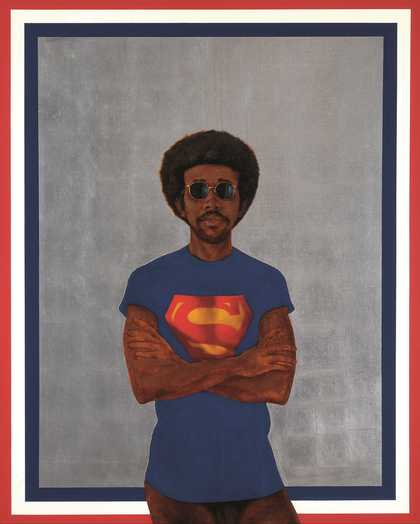

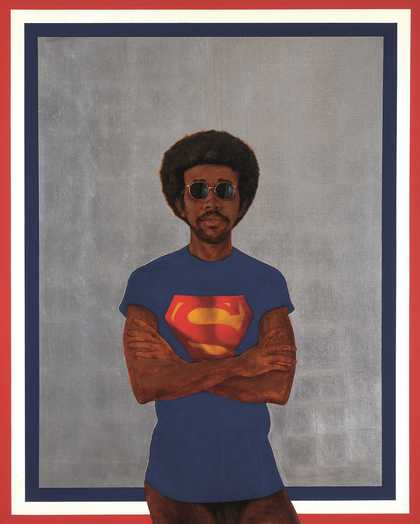

Barkley L. Hendricks Icon for My Man Superman (Superman Never Saved any Black People – Bobby Seale) 1969 Collection of Liz and Eric Lefkofsky © Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Superman S-Shield © & ™ DC Comics. Used with permission

I wasn’t ever interested in speaking for all Black folks. Much of what I was trying to do with my work was to be as good a painter as I could be.

Barkley Hendricks

The concept of the ‘Black Hero’ was proposed by the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), presented in Room Two, who said that:

a Black Hero is any person who honestly reflects the beauty of Black life and genius in his or her style; does not forget his Black brothers and sisters who are less fortunate; does what he does in such an outstanding manner that he or she cannot be imitated or replaced.

Looking to represent people historically excluded from ambitious figurative painting, artists also defined a Black hero as a person who plays a role in everyday life. For instance, Emma Amos’s babysitter, whose child care work allowed the artist’s career to flourish.

Although the artists here created positive pictures of African Americans, most aimed to make the best paintings of their time, rather than seeking to represent Black America. Raymond Saunders painted boxer Jack Johnson, the first African American world heavyweight champion, but in his text ‘Black is a Color’ of 1967, insisted that the Black artist should be free to use colours, just like any other painter, without symbolism. Barkley Hendricks taught himself how to use metal leaf to literally make himself an icon, having first seen Byzantine icons on a trip to Europe.

Room ten: Improvisation and experimentation

In the early 1970s, many of the artists included in Room Seven (East Coast Abstraction) moved away from the conventions of abstract painting and sculpture, and began experimenting with materials and forms. For some artists and critics, this commitment to improvisation and experimentation connected to Black Americans’ ambitions for political freedom.

Room ten tracks

- Pharaoh Sanders Hum-allah-hum-allah-hum-allah

- Don Cherry Utopia and Visions

Find out more about room ten

It is necessary to be free enough to create beyond the boundaries of any aesthetic … To improvise is the only real and constantly dynamic revolutionary way to be.

Melvin Edwards

Sam Gilliam took the canvas off the stretcher, knotting it at places along the top and hanging from these points so its folds would change from one showing to the next. Jack Whitten created a rake-like implement that he called a developer, and used it to move layers of acrylic paint across a canvas stretched out on the studio floor. Alvin Loving turned away from painting geometrical shapes, instead cutting up and collaging old paintings and adding strips of cloth, leather and fur, seeing his new works as an affirmative answer to the question ‘is there a black art?’

Artists looked back to a history of oppression while celebrating present-day community and looking forward to a brighter future. Evoking slavery and incarceration, Melvin Edwards used barbed wire and chains in a series of sculptures, but titled them in homage to friends. Joe Overstreet created gridded canvases strung up away from the wall, recalling, for him, a history of lynching, but defiant in their colourful optimism.

Bold colours also characterised Alma Thomas’s paintings, made in the wake of a NASA mission to Mars, and Frank Bowling’s Map Paintings, where vast continents appear to dissolve into and emerge from oceans of liquid paint.

Room eleven: Betye Saar

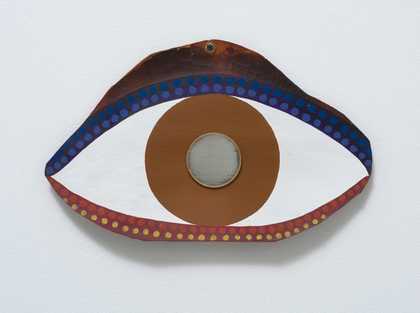

Betye Saar Eye 1972 Collection of Sheila Silver and David Limburger © Betye Saar. Courtesy of the Artist and Roberts & Tilton, Los Angeles, California. Photo Robert Wedemeyer.

In 1970, Betye Saar reached a turning point in her art-making. She attended the National Conference of Artists in Chicago, an annual gathering of African American artists, with fellow artist David Hammons.

Room eleven tracks

- Alice Coltrane My Favorite Things

- Alice Coltrane Journey in Satchindananda

- Betty Davis They Say I'm Different

I’m intrigued with combining the remnant of memories, fragments of relics and ordinary objects, with the components of technology. It’s a way of delving into the past and reaching into the future simultaneously. The art itself becomes the bridge.

Betye Saar

As part of Saar's trip with Hammons, they visited the Field Museum’s collections of African and Oceanic art, which awakened in Saar an interest in ancestral connectedness, ritual objects and their spiritual power. The artist said:

In October 1973, her first survey show BETYE SAAR 1964–1973 was on view at the Fine Arts Gallery, California State University, L.A. Here we re-create one aspect of that solo exhibition. Its catalogue detailed the memorable subject matter:

Saar was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts grant in 1974, which allowed her to travel to Haiti to study local religious practices and belief systems. Later in 1977, she participated in FESTAC in Lagos, Nigeria, the largest ever pan-African cultural festival. Spirit Catcher, displayed in this room, comes out of her research on these travels.

Room twelve: Just above midtown

Lorraine O'Grady Art Is. . . (Girlfriends Times Two) 1983/2009 Private Collection © Lorraine O’Grady/Artist’s Rights Society (ARS), New York many pieces grid

On 18 November 1974, JAM first opened its doors. Just Above Midtown gallery was founded by Linda Goode Bryant, former Director of Education at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Room twelve tracks

- The Last Poets Black Is

- Sun Ra Space is the Place

- Billy Paul East

Find out more about room twelve

I was motivated to pursue a way to change conditions that were causing Black artists I interfaced with every day to say, ‘they won’t let us'. I got tired of hearing that, and I said, ‘Fuck them! Let’s start a gallery'.

Linda Goode Bryant

JAM did what the rest of the New York art world didn’t – recognise the work being made by African American contemporary artists and provide a platform for their art to be seen and sold. Such was the appetite for this new space that opening night attendees spilled out of the gallery, onto the Manhattan street.

JAM made a unique commitment to representing new work, like Dawoud Bey’s photography and Randy Williams’s sculptural reliefs. Though New York-based, JAM regularly featured the Los Angeles community of artists, as seen in Room Four. The gallery also championed avant-garde artists such as Senga Nengudi, who produced sculptures made from nylon stockings she could interact with or ‘activate’. Lorraine O’Grady orchestrated the ambitious and inclusive performance Art Is… at the Harlem African American Day Parade, supported by JAM in 1983.

JAM’s artistic programme also included $5 lunches featuring a 30-minute talk with artists, critics or curators. When visitors first encountered David Hammons’ works made with greasy bags, barbecue bones and Black hair, Goode Bryant staged an on-the-spot discussion so everyone could share their opinions about Hammons’ art. JAM also showcased performance and music, providing a welcome to those unused to visiting exhibitions of modern art.

JAM closed its doors in 1986, having redefined itself with every project.

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power is on at Tate Modern 12 July – 22 October 2017