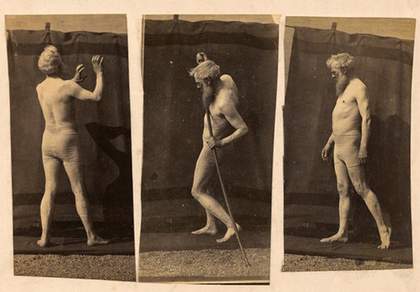

Fig.1

Francis Bacon

Study for Self-Portrait 1963

Oil paint on canvas 1652 x 1426 mm

© National Museum of Wales

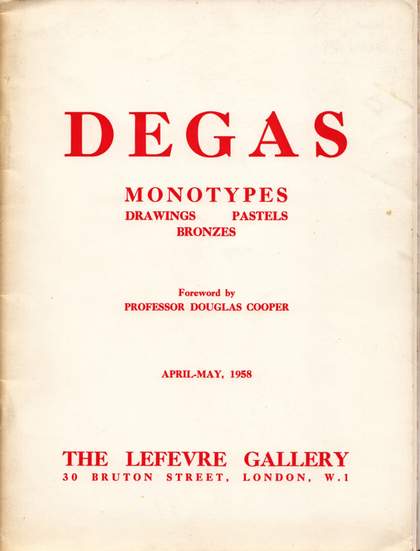

There is nothing like a pair of matching sofas for sparking off a conversation. In the case of this first juxtaposition, both are blue, with rounded backs, set against off-white walls and plain light brown floors (figs.1–2). Both are accompanied by middle-aged males in postures suggesting private contemplation, who have set aside their cigarette or pipe, as well as their well-thumbed papers, and who either sit or put their feet up on rather more flimsy items of wooden furniture. Each picture subverts the social transaction traditionally inherent in portraiture, evoking instead states of inwardness and the casual clothing and sparse environment of the modern bohemian. It was observing such affinities between Edgar Degas’s portrait of his critic friend Diego Martelli 1879 (National Galleries of Scotland), and Francis Bacon’s Self-portrait 1963 (National Museum of Wales), that triggered the exploration that follows.1 The two pictures are very different in ways that are typical of their makers: Degas’s dispassionate observation and daringly asymmetrical composition and high viewpoint, as opposed to Bacon’s symmetry, simplification and abstraction from appearances. Nevertheless, the parallels seem striking enough to go beyond coincidence and to provoke speculation about what Degas meant to an artist born seventy-five years later, who worked long after the demise of naturalism and, indeed, in the aftermath of cubism, abstraction and surrealism. The question, then, is what might have motivated Bacon to look all the way back to Degas?

Fig.2

Edgar Degas

Diego Martelli 1879

Oil paint on canvas

1104 x 998 mm

© National Galleries of Scotland

Bacon once observed that ‘to create something … is a sort of echo from one artist to another’.2 The mainstream texts on his work tend to emphasise the places Bacon encountered, the people he knew, and the terrible times he lived through, as though his work adds up to a kind of psychological autobiography. This is overstated and simplistic, even if Bacon in other moods encouraged such readings. Art does come out of life, but in an indirect and more complicated fashion than this type of commentary implies. What is more demonstrable is that major artists engage with past and present art as a resource in itself, in developing the aesthetic means to embody whatever content they have in mind. This was certainly true of Bacon, who insisted that he looked at everything. Quite a lot is now known about his visual and imaginative reactions to photographs, which he worked from more consistently than almost any other modern painter. But we are at a rudimentary stage in grasping how Bacon responded to the work of other artists. The theme encompasses his quotations from Old Masters such as Velázquez, Rembrandt, Grünewald and Ingres; and his appropriations from such immediate predecessors as Picasso, Sickert and Soutine; as well as his interchange with contemporaries such as Sutherland and Giacometti.3 Bacon also declared great admiration for several late nineteenth-century artists such as Monet, Gauguin, Rodin, Seurat and, above all, van Gogh. But this essay focuses on Degas, and can only hint that Bacon’s interest in the work of these artists is much more jumbled up than a crude listing makes out.4

Artists scrutinise other artists in distinctive and idiosyncratic ways, through the filter of their own preoccupations.5 But Bacon’s take on Degas was also shaped by the works he happened to confront, and whose availability reflected decisions made by other people about acquiring works for museums, selling them in galleries, and displaying them in exhibitions. In that sense, Bacon’s artistic assimilation is one component within the larger story of the British response to Degas, which began as early as the 1870s, and is of course still alive and well.6 In between, we might note the commercial Degas show at Agnew’s, London, in 1936, the year before a group show in the same gallery in which Bacon participated; and further exhibitions in 1950 and 1958 at the Lefevre Gallery, which had also staged Bacon’s emergence in another series of group displays in 1945 and 1946.7 Many of the best works by Degas in British public and private collections were brought together in a major exhibition in Edinburgh and then at the Tate Gallery in 1952. Then there were the works and exhibitions Bacon could have seen on trips to Paris, which may well have been more frequent than is currently known. At any rate, Bacon had ample opportunity to engage with Degas in the original – over and above the increasingly vivid reproductions that were becoming available – and this essay will try to pin down what he gleaned from such specific encounters.

Fig.3

Edgar Degas

Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando 1879

Oil paint on canvas

1172 x 775 mm

The National Gallery, London

© The National Gallery, London/Scala, Florence

In Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion c.1944 (Tate N06171), the work in which Bacon came to believe he had discovered his artistic identity, the disquieting hybrid creatures pay homage to the grotesque anatomical distortions and sculptural presence of a particular phase in Picasso’s art around 1930, focused upon bather imagery.8 Bacon’s three images almost certainly started life as separate pictures, and the decision to bind them together visually into a triptych was realised in part by superimposing around the figures’ contours a consistent backdrop of unmodulated orange, with minimal perspective indications. One critic has drawn a visual parallel with Degas’s Combing the Hair c.1896 (National Gallery, London), which had been acquired for the national collection in 1937.9 In the wake of Degas’s death in 1917 and the sales of his studio contents, the interwar years were a key moment for the acquisition of works by British institutions, works that tended to be shown initially at the Tate Gallery and were only later sent to their present home in Trafalgar Square. Another work already in public hands, Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando 1879 (National Gallery, London), was an even more telling model to Bacon for the floating three-dimensional form set against a backdrop of strong, flat orange, which Degas also superimposed late on, to offset the figure and perspective construction (fig.3).10

Fig.4

Edgar Degas

Ballet Dancers c.1890–1900

Oil paint on canvas

725 x 730 mm

The National Gallery, London

©The National Gallery, London/Scala, Florence

The triptych also indicates Bacon’s interest in a third Degas that had entered the national collection as early as 1926, namely the late Ballet Dancers c.1890–1900 (National Gallery, London; fig.4). Discussing the left-hand picture of the triptych (fig.5), Martin Harrison has noted that Bacon appropriated the head in profile from one of the photographs in an old book he owned about ectoplasms and mediums.11 But it is almost as though Bacon homed in on the particular illustration that reminded him of the treatment of the head in the nearmost dancer in the Degas. That figure certainly seems to be the springboard for the configuration of the upper body, where Bacon exaggerates the indentation between the two rounded shoulder blades, and the extension of the spine into the neck, which in his hands becomes elongated and downwards inclined. The slender white straps and emphatically curved forms seem to secure the connection with Ballet Dancers, as do the placement of his creature’s knee and the angle of the stool on which it rests. In sum, the Bacon figure starts to look like an unlikely composite of the photograph, the Degas, and Picasso bather imagery. Such things appear ‘mixed up’ in his mind in much the same way that Michelangelo and Eadweard Muybridge converged, Bacon famously remarked, in his imaginative projections of the male body.12 Moreover, it is likely that Bacon was excited by the painterly freedom of Ballet Dancers, the bold and diverse marks, made with the artist’s fingers perhaps in places, applied onto coarse unprimed canvas which is left substantially exposed, especially to the right of the picture.13 Bacon, too, often left canvas bare, as in the central panel of the 1944 triptych. He subsequently took to painting on the rear, rougher side of his supports, to heighten the contrast between the visual textures of granular canvas and smeared, scumbled paint marks. It is even possible to speculate that Degas’s necessary recourse to glazing large pastels might have reinforced Bacon’s impulse to use glass in framing his paintings, for practical reasons initially, perhaps, but thereafter on aesthetic grounds. At any rate, Ballet Dancers suggests that late Degas was a key point of departure for the sense of layering and variable degrees of sharpness and blur, the sense of an image suspended in the course of its improvisation into being, that remained fundamental to Bacon’s art.

Fig.5

Francis Bacon

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion c.1944 (left panel)

Oil paint on board

940 x 737 mm

© Tate

At the same time, Degas demonstrated to Bacon how emphatically pictorial statements could emerge out of a process of appropriating photographic imagery. Degas’s overt exploitation of photography was announced in another London picture, the early Princess Pauline de Metternich c.1865 (National Gallery, London), famously based on a carte de visite. Given Bacon’s immersion in Muybridge, he may well have sensed the strong link between the late nineteenth-century photographer and the contemporary work of Degas.14 Bacon’s friend and interlocutor David Sylvester made the connection as early as 1954, noting Bacon’s exploitation of Muybridge’s ‘great photographic compendium – which served Degas in a quite different fashion – of human and animal locomotion’.15

Fig.6

Edgar Degas

After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself c.1890–5

Pastel on paper on board

1035 x 985 mm

The National Gallery, London

© The National Gallery, London/Scala, Florence

A process of compacting visual sources may be evident again in Study from the Human Body 1949 (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne), which was executed shortly before being included in Bacon’s one-man show at the Hanover Gallery in late 1949. A fascination with the image of the human back is one of the more obvious common denominators between Bacon and Degas. After Bacon’s death, Sylvester remarked of Study from the Human Body: ‘The figure is the first of many which show an undying love for the Degas pastel in the National Gallery, London, of a woman drying herself.’16 For Bacon, After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself c.1890–5 (National Gallery, London) was indeed something of a talisman (fig.6). It epitomised Degas’s approach to a larger obsession the two artists shared with the plasticity of the body, its potential for the most varied forms of articulation, in movement and repose. But when did Bacon encounter After the Bath? Sylvester’s authoritative tone suggests that he was remembering its discovery around the time that he and the artist first got to know one another. This particular Degas was not in fact acquired by the National Gallery until 1959. However, it was shown in the Lefevre Gallery’s Degas show in 1950, and there is no record of a previous public showing.17 After the Bath was then purchased by the collector Harry Walston from the exhibition (though it was twice lent to the Tate Gallery for a few months before finally being acquired for the nation).18 It is possible that Sylvester was conflating the work with the equally remarkable Degas bather pastel in the Courtauld collection, shown in a memorial display at the Tate Gallery in summer 1948; equally, before its exhibition, Bacon may have encountered After the Bath informally at the Lefevre Gallery, where he had exhibited and was well known.19 At any rate, such quintessential Degas imagery seems to have fed into Bacon’s first variant on the toilette theme, the Painting 1950 (Leeds Art Gallery), fusing with impressions derived from a Sickert drawing identified by the art historian Rebecca Daniels.20

From a different perspective, Degas’s After the Bath was again in Sylvester’s thoughts when discussing the remarkable Study after Velázquez 1950 (private collection), one of Bacon’s very first pope pictures. The critic evoked Bacon’s reinvention of the curtain motif here in less literal terms:

The short folds in the purple cape and the long folds in the grey background curtain together create a wonderful counterpoint … He had observed in certain late Degas pastels the use of sets of close parallel lines that seemed to be passing through a semi-transparent body. Bacon’s development of this usage, which he called ‘shuttering’, was to formalize the folds in background curtains into stripes that passed very emphatically through a figure. I asked him once if he could explain why Degas’s shuttering could be so poignant. ‘Well, it means that the sensation doesn’t come straight out at you but slides slowly and gently through the gaps.’21

Degas himself would not perhaps have put it like that. Rather, the remark captures Bacon’s own, highly metaphorical sense of pictorial devices. In a later interview, the artist remarked of Degas’s pastels: ‘he shuttered the body, in a way, shuttered the image and then he put an enormous amount of colour through these lines.’ For Bacon, this device ‘created intensity’.22 In Study after Velázquez, any such impressions from Degas fuse with more direct derivations from black and white photography. Bacon would, for example, have known Erich Salomon’s photograph, reproduced in Picture Post magazine in 1947, where the great and the good are captured, unaware and unposed, through a diaphanous curtain.23 Another possible model is pre-war Nazi propaganda imagery, specifically the spectacle of the ‘cathedral of light’ that Albert Speer devised for the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games and the culminating ceremony at the Nuremberg rallies, in which parallel beams of light directed into the night sky register as densely packed stripes of light and dark.24 Bacon was fascinated by the gulf between the Nazi propagandist façade and the ruthless will to power that it veiled. A terminology akin to shuttering came to mind when he talked, in a somewhat Nietzschean vein, about his aims: ‘We nearly always live through screens – a screened existence. And I sometimes think, when people say my work looks violent, that I have from time to time been able to clear away one or two of the veils or screens.’25 Bacon surely saw Degas, Nietzsche’s near contemporary after all, as the exemplary artist who cut through to raw human realities.

The light and dark striations generally recede into the background in Bacon’s work from the first half of the 1950s. In the foreground, the Degas-like motif of the naked figure viewed from the back is restated in a sequence of pictures from 1952, including Untitled (Crouching Figures) (Estate of Francis Bacon) and, above all, Study for Crouching Nude (Detroit Institute of Arts) that was one of Bacon’s favourite works.26 The theme allowed him to channel visual suggestions from such varied sources as Muybridge’s photography, Michelangelo drawings, Rodin sculptures and from classical antiquity, which have all been seen as catalysts.27 Or Degas may again be cited, such as the nude drying herself, unusually oriented to the right, which had been shown at the Lefevre Gallery show two years earlier.28 But such points of reference interacted with an even more direct springboard in photojournalism for Bacon’s conception of the figure. For Bacon, the image of the back edited out the individuality implicit in facial features and so projected an animalistic sense of humanity. The association is reinforced here by the squatting or crouching posture that recalls the body language of apes, complementing the cage-like setting. For his part, Degas famously remarked that women at their toilette were like cats washing themselves, and the application to his work of the term ‘human animal’ goes all the way back to the writer Joris-Karl Huysmans.29 In 1952 Bacon was actually working from an illustrated feature article that had appeared in the same 1947 issue of Picture Post magazine about a lioness attacking a photographer in the wild.30 Bacon was clearly mesmerised by the largest image, in which the seated lioness seems to take on an incongruously gentle and protective attitude towards the recumbent figure, and to take on a decidedly anthropomorphic appearance. In Study for Crouching Nude the image of an animal with human attributes is metamorphosed by Bacon into a figure with animal undertones. Aside from the articulation of the body, the relationship with the photograph is implicit in the pool of shadow to the right of the figure, and in Untitled (Crouching Figures) and several related pictures by the inclusion of elements of the lying figure with bent legs. Here the imagery takes on unmistakable homoerotic overtones, almost as if the instinctive violence of the kill is converted in Bacon’s imagination into some sadomasochistic fantasy. The photograph was Bacon’s immediate source, but Degas remains in play if we concur with the art historian John Rothenstein’s description in 1964 of a typical mechanism in Bacon’s creativity: ‘his images often derive from a variety of photographs of different subjects and these may be fixed or coloured by his memory of still some other thing seen or remembered.’31 This remark captures a very visual process of transformation and synthesis that is bound to be travestied in any verbal description.

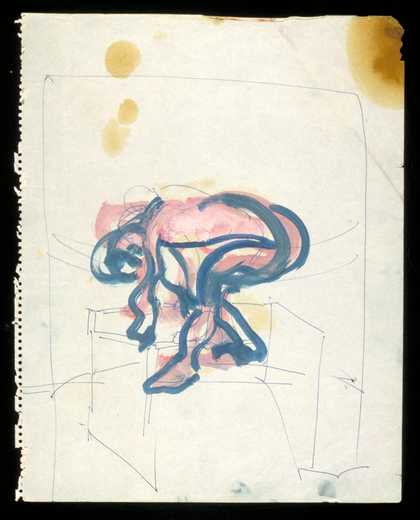

Several new departures are evident in Bacon’s art of the late 1950s and into the 1960s, in the aftermath of the variations on a van Gogh self-portrait that Bacon hurriedly executed in 1957. These developments include, first, a proliferation of naked figures, and in particular of female bodies, hitherto a rarity in Bacon’s work; secondly, an emphasis on the overall articulation of the body, which is sometimes more dynamically charged, but in general becomes more sculpturally defined, against simpler and increasingly colourful backdrops; thirdly, a move away from the photographic effects of grisaille, blur and inconsistent focus that had been dominant a few years earlier; and, fourthly, an espousal of working on paper.32 Although Bacon always denied that he drew, a significant cluster of cursory sketches have since come to light, with provenances among Bacon’s circle, but without any signatures or dates. The bulk were acquired by Tate and exhibited in 2003. Curator Matthew Gale convincingly ascribed the bulk of the drawings to around 1957 to 1961, on the basis of documentary evidence as well as visual correspondences with paintings dated from 1959 to the early 1960s.33 It is the hypothesis of this essay that these various new directions register in part Bacon’s assimilation of a fresh aspect of Degas.

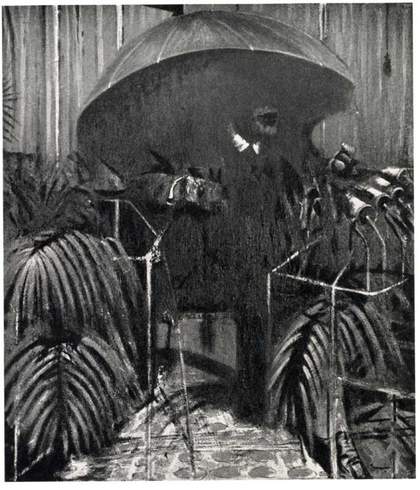

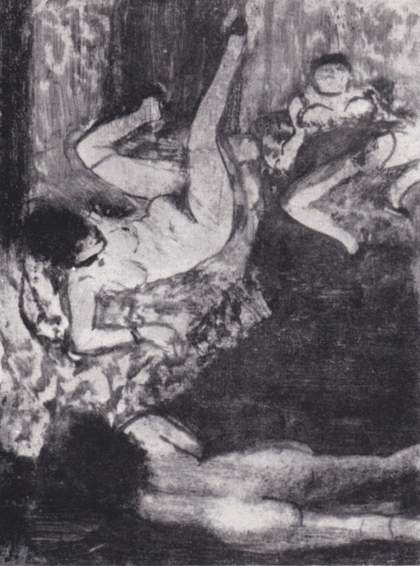

Fig.7

Cover of Degas. Monotypes, Drawings, Pastels, Bronzes, exhibition catalogue, Lefevre Gallery, London, April–May 1958.

Bacon is very likely to have seen the Lefevre Gallery exhibition Degas. Monotypes, Drawings, Pastels, Bronzes, staged between April and May 1958. It was accompanied by a bigger catalogue than usual, with all works illustrated and with an essay by Bacon’s long-time acquaintance Douglas Cooper, setting Degas within the wider history of the monotype (fig.7).34 Indeed, although there was a handful of works in the other media, the undoubted revelation of the show was the thirty-six monotypes, one-off images pulled from a sheet of metal on which the artist had improvised the image in printers’ ink, with radical freedom of touch and economy of means (at times working with his fingers and with rags). This was a strand in Degas’s work that had hitherto been relatively unknown in Britain compared with the paintings, pastels and sculpture. No monotypes, for instance, had been shown at the Tate Gallery six years earlier. Their impact would only have been enhanced for Bacon by the well-founded rumours that Picasso was keen to purchase several brothel monotypes from the London exhibition.35 The works on show in 1958 are at the opposite end of the spectrum from Degas’s elegant ballet and race track pictures. Their earthy sensuality and bleak atmosphere were evoked at the time in the pages of the Burlington Magazine:

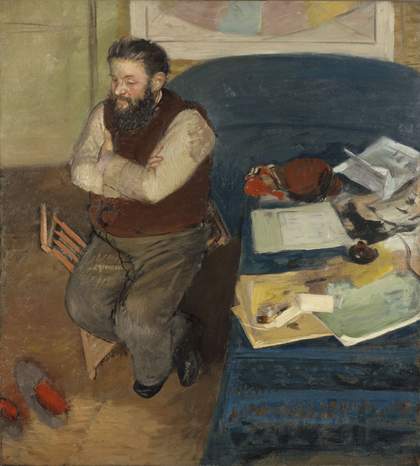

Fig.8

Edgar Degas

Rest c.1879

Monotype 159 x 108 mm

From Degas. Monotypes, Drawings, Pastels, Bronzes, exhibition catalogue, Lefevre Gallery, London, April–May 1958.

nothing can mitigate the wretchedness of their [the prostitutes’] existence. Degas is prepared with Goya-like mercilessness to drain away all vestige of lying glamour in order to distil this disagreeable truth. The women are hideous, fat, no longer young; their clients shifty, and horribly respectable with their umbrellas and bowler hats … his attitude towards all such sad exploits of human beings was never compassionate. Rather he was deeply concerned with truth for its own sake, in probing life beneath the crust of good manners … He knew just how thin this crust was, and took a defiant delight in exposing the squalor that lay below it. We who still like for the sake of a little piece of mind to pretend that the crust still holds, are put in our place by the spectacle of all grace, all varnish, being ripped away with so much genius to reveal the raw facts.36

While the words of this review may echo any number of contemporary reactions to Bacon’s paintings, what is the visual evidence that these works by Degas struck a chord with Bacon? The abject, contorted naked women, in minimal interiors, who feature in Bacon’s art over the next two or three years suggest a general continuity with the Degas monotypes. More specific affinities exist between the drawn Figure in a Corner and one such Degas: in both, the figures’ arms are stretched out, and one leg is extended and the other bent, with the genitals prominently displayed, while the bed or sofa on which they disport themselves recedes diagonally into a shallow space.37 In several of the monotypes Degas’s women recline and doze, perhaps in a state of post-coital stupor (fig.8). Likewise recumbent figures abound in Bacon drawings, as in Figure Lying No.2 (Tate T07375), and related paintings such as Sleeping Figure 1959, a tender depiction of his lover Peter Lacy.38 In its unselfconscious body language, remote from the posing of the traditional nude, the latter may incorporate Bacon’s recent memories of the girl conceived by Degas for Rest c.1879 (Musée Picasso, Paris), one of Picasso’s acquisitions. The same monotype includes a fragmentary glimpse of a male customer entering the space which may have been a point of reference at some level for Bacon’s enigmatic Walking Figure 1960 (Dallas Museum of Art). Bacon’s nudes lying upside down on sofas, in works on paper (such as Reclining Figure No.1 and Reclining Figure No.2; Tate T07353–4) and on canvas – as in Reclining Woman 1961 (Tate T00453; fig.9) – recall the postures in several monotypes, which show prostitutes relaxing on upholstered couches (fig.8).39 Figures viewed from the back occur in several of Degas’s prints and drawings in the Lefevre Gallery exhibition, as they do in Bacon sketches like Standing Figure (Tate T07367), an especially economical image that possibly incorporates a recollection of one of Degas’s naked girls.40 Finally, Figure Bending Forwards (Tate T07358) and Bending Figure No.2 by Bacon (Tate T07379; fig.10) bring to mind the more contorted bodies in Degas’s imagery of girls at their toilette (fig.11), although Muybridge’s photographs are also relevant here.41 Generally, Degas and Muybridge seem to have coalesced for Bacon within this body of work.42 It is not possible to say for sure that Bacon saw these works by Degas. But the cursory discussion above indicates that there are sufficient visual and thematic parallels, across a fair proportion of Bacon’s work known or thought to date from the subsequent period, to support the proposition that the Lefevre Degas show in spring 1958 was a significant catalyst.

Francis Bacon

Sketch [Bending Figure, No. 2] (c.1959–61)

Tate

Its fascination for Bacon may have gone beyond iconography. The exhibition might also have prompted him to explore the possibilities of drawing. The current view is that Bacon turned to working on paper in the late 1950s as something of a temporary expedient, in order to help him resolve his current pictorial problems.43 If that is correct, which is impossible to prove since earlier and later graphic production could be lost, then Bacon might well have derived sustenance from Degas’s monotypes. Their extraordinary daring and lack of inhibition, in relation to both imagery and technique, would surely have resonated with Bacon. At the same time, they demonstrated how an artist might choose working on paper, on an intimate scale, as a vehicle for private studio experimentation and perhaps for erotic reverie, producing images that only became public after the artist’s death. In other words, they showed how drawing could be something other than a practical instrument for developing ideas for paintings, which was anathema to Bacon given his commitment to improvisation on the canvas.

Fig.11

Edgar Degas

Breakfast After the Bath, Young Woman Drying Herself c.1896

Charcoal and pastel on paper

762 x 489 mm

From Degas. Monotypes, Drawings, Pastels, Bronzes, exhibition catalogue, Lefevre Gallery, London, April–May 1958.

The argument about the Degas monotypes makes sense in relation to Bacon’s wider evolution. The period around 1960 tends to be rather glossed over, even by the Tate’s 2008 retrospective, reflecting its problematic aesthetic status. The one point that is regularly made is that Bacon’s simpler, colourful backdrops reflect his new awareness of American abstract expressionism and its St Ives equivalent in current British art, reinforced by his three-month stay in Cornwall in 1959.44 Yet, paradoxically, Bacon’s move towards a more animated treatment of the human body may in part have represented a reaction against abstraction, a type of art which lacked meaningful content in Bacon’s view. He may have been appropriating abstract devices for his backdrops in a spirit more of parody than emulation. An intensified interest in Degas, on the other hand, would be entirely compatible with the broader engagement with late nineteenth-century French art that informed Bacon’s art at this point. This extended notably to Rodin’s sculpture, analogous of course to Degas in its brutal realism and bodily contortions. Rodin was mentioned admiringly by Bacon in his lists of possible new pictures, and was proposed by Matthew Gale as a springboard for Bacon’s ‘distortion and idiosyncratic articulation of the human figure’ at this juncture.45

By general consent, Bacon hit his artistic stride again in the early 1960s, a moment which roughly correlates, coincidentally or otherwise, with the new contentment in his personal life associated with meeting George Dyer. The period from then until the mid-1970s was one of the undoubted peaks in Bacon’s art. His sense of himself as a latter-day realist comes through strongly in the concurrent interviews with David Sylvester. Correspondingly, Bacon’s engagement with Degas becomes more overt, one element in a Francophilia that was apparent in the satisfaction he derived from being invited to stage a big retrospective at the Grand Palais, Paris in 1971, in his acquisition of a flat in Paris, and in his several friendships at this time with French artists and writers, notably Michel Leiris. It is plausible that Bacon identified with Degas as a fellow spirit, a model for his own devotion to ‘the human clay’, in W.H. Auden’s resonant phrase, and thus as the antidote to a contemporary scene dominated by abstraction and pop art, from which Bacon felt increasingly isolated.

His new immersion in portraiture, for instance, was bound up with his admiration for Degas, as has already been indicated. Bacon no doubt perceived that, in works like Diego Martelli, shown in London in 1952, Degas had taken portraiture off its pedestal in much the same way that the women at their toilette pictures brought the image of the nude down to earth, locating it within contemporary everyday experience and the private sphere. In the Martelli portrait, the pose served to convey the singular physical and psychological presence of Degas’s sitter, and to evoke a fictive obliviousness to the observing artist, rather than the social front that is normally encountered in portraits. Its enduring impact is evident in the more exaggerated body language of Bacon’s Three Studies of Lucian Freud 1969 (private collection), ‘awkward in his squirming pose’ in Chris Stephens’s words, as well in certain late self-portraits such as Self-Portrait with a Watch 1973 (private collection).46 Bacon’s immediate points of reference were often photographs by John Deakin, but in directing the conception and making of these, Bacon may well have had Degas at the back of his mind. The George Dyer images from the 1960s, such as Study of George Dyer in a Mirror 1968 (Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid), raise the further point that including paintings within paintings is an interesting sub-theme in both artists’ approaches to portraiture.47 At the other end of the scale spectrum, the robust physicality and rich tonality of Degas’s Head of a Woman c.1874 (Tate N03390; fig.12), another early acquisition for the national collection, may have been an example for Bacon’s head and shoulder portraits form the early 1960s onwards, especially in the many, robustly sensual depictions of the artist and model Isabel Rawsthorne.

Edgar Degas

Head of a Woman (c.1874)

Tate

Dyer inspired other works that went beyond straightforward portraiture. In the 1964 triptych Three Figures in a Room 1964 (Centre Pompidou, Paris), a playful and erotically charged love letter, Bacon’s apparent feminisation of the naked figure is accentuated by his allusions to Degas. The centrepiece of Dyer in repose on a couch recalls Degas’s imagery of the boudoir interior as a place of serenity and bodily pleasure while the right-hand depiction of his lover swivelling on a barstool evokes the ungainly poise of Degas’s sculpted ballet dancers, exemplified by the two bronzes acquired by Tate in 1949 and 1951.48 At the same time, the dance studio interiors could have encouraged Bacon to distil the luminous, simplified spaces that offset his increasingly plastic figures. Most obviously, Degas’s imagery of women at their toilette is transposed in the left-hand panel of the triptych into Bacon’s depiction of a man literally sat on the toilet, which it is hard not to see as light-hearted, even an in-joke, if Bacon is permitted to depart from tragic mode. The visceral physicality that he saw in Degas turns into a projection of Bacon’s own muscular ideal. Here, and above all in the depictions of the male toilette in Three Studies of the Male Back 1970, Bacon paid his most explicit homages to Degas’s After the Bath, by then on permanent display in the National Gallery. In between making the two triptychs, Bacon explained to Sylvester in their 1966 conversation what it was that he found so riveting about that particular Degas: ‘You will find at the very top of the spine that the spine almost comes out of the skin altogether. And this gives it such a grip and a twist that you’re more conscious of the vulnerability of the rest of the body than if he had drawn the spine naturally up to the neck. He breaks it so that this thing seems to protrude from the flesh.’49 The most literal elaboration of this idea in his own work occurs in Three Figures and Portrait 1975 (Tate T02112), though here virtuosity comes perhaps at the expense of vulnerability.

The first half of the 1970s may well have been the period in which Degas meant most to Bacon. Sylvester shrewdly noted that Triptych 1974–7 (private collection) ‘surely contains Bacon’s most complex homage to Degas’:

The two male backs are among the many in his work which are indebted to the Degas pastel in the National Gallery of a woman sponging her back; the horses with rider also recall Degas; and the whole atmosphere must be indebted … to a further Degas in the National Gallery, the Beach Scene: the panorama of sands and sea and sky, the contrast between figures near and far, the umbrellas, the way that shadows and pieces of fabric are silhouetted against the sky.50

Bacon proceeded to include After the Bath in his The Artist’s Choice exhibition, staged in 1985 at the National Gallery, London, with the Degas on the cover of the accompanying pamphlet. The actual picture was hung in the middle of three nudes occupying what Sylvester recalled as ‘the best wall’, flanked by Velzáquez’s Rokeby Venus 1647–51 and Michelangelo’s Entombment c.1500: ‘Degas was seen as the progeny of the masters on either side, and thus as Bacon’s key painter.’51

Others who knew Bacon well picked up on this reverence for Degas. In the first, but still the most suggestive monograph, the art critic John Russell lingered over the importance of After the Bath but observed too: ‘since Degas was a great student of people in rooms, it is natural that Bacon should often have studied the paintings in which Degas brought off just that element of psychological ambiguity which Bacon himself often strives for’ – a point Russell illustrated with Degas’s early Interior c.1868–9 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), a picture which does indeed presage the air of indeterminate menace in, for instance, the central panel of Bacon’s Triptych – In Memory of George Dyer 1971 (Fondation Beyeler, Basel).52 Subsequently, the biographer Michael Peppiatt quoted Bacon thus: ‘I love Degas. I think his pastels are among the greatest things ever made. I think they’re far greater than his paintings.’53 And from Peppiatt himself: ‘Bacon had obtained a copy of the rare Lemoisne catalogue raisonné of Degas’s work and he kept it in the studio during this period, frequently leafing through the hundreds of images that Degas, whom he admired more than any other nineteenth-century artist save van Gogh, had created.’54

Fig.13

Francis Bacon

Sand Dune 1983

Oil paint and pastel on canvas

1980 x 1475 mm

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel

Photograph © Peter Schibli, Basel

© 2012, DACS, London

Visual parallels with Degas occasionally make themselves felt in Bacon’s work from his final decade or so. It is interesting to note that both of these committed recorders of the human form were unusually drawn in their later careers to imagery of landscape, although the knobbly, rounded forms that both of them explored in the natural world were redolent of bodily associations. Compare, for instance, Bacon’s Sand Dune 1983 (Fondation Beyeler, Basel; fig.13) with Degas’s late coastal scenes, for example Le Cap Hornu near St Valery-sur-Somme c.1890–3 (British Museum; fig.14). One of Bacon’s very last pictures, Study for the Human Body 1991, presents striking parallels of scale, imagery and palette to Degas’s Dancers at the Bar c.1900 (Philips Collection, Washington), notwithstanding the gulf between Degas’s slender, immaterial females and Bacon’s body-building beefcake.55

Fig.14

Edgar Degas

Le Cap Hornu near St Valery-sur-Somme c.1890–93

Monotype

299 x 399 mm

The British Museum

© Trustees of the British Museum

A feature of Degas’s later art that Bacon is likely to have found exciting was its combination of taut, analytical drawing of the structure of the body, in defined spatial settings, with sparse expanses of painterly texture and increasingly arbitrary flat colour, including the bright oranges to which Bacon was especially devoted. Equally, the acidic greens encountered in late Degas, such as A Group of Dancers c.1890 (National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh), are the most striking precedent for Bacon’s audacious viridians, epitomised by Crouching Nude 1961.56

In general, what Bacon admired in Degas was the sensation of visceral reality, created not merely through description but also by the knowing manipulation of paint marks on a flat surface, beneath the effect of spontaneity that both cultivated. An underlying affinity of attitude is evident by juxtaposing a typical comment made late in life by Bacon – ‘The more artificial you can make it, the greater chance you’ve got of its looking real’57 – with remarks attributed to Degas such as: ‘One gives the idea of truth by means of the false’ and ‘”Art” is the same word as “artifice”, that is to say, something deceitful. It must succeed in giving the impression of nature by false means’.58 Moreover both artists were neurotic perfectionists, prone to asking if they could take back for revision works they had completed and even sold. Each went so far on occasion as to destroy the work in question, and unsurprisingly both had such requests turned down by wary owners, by the Tate in fact in Bacon’s case, when in 1966 he asked to add a green carpet to Study for Portrait on Folding Bed 1963 (Tate T00604), acquired three years earlier;59 and by the owner and friend of the artist Henri Rouart, when Degas asked if he could modify Dancers Practicing at the Barre 1877 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), having come to regret the visual analogy between the watering can, commonly used to sprinkle the floor to suppress dust, and the pose of the rightmost dancer.60

It is tempting as well to see Bacon’s attitude to artistic media as reflecting his awareness of Degas. His mixing of pastel and paint, especially in the 1940s, may reflect a fascination with the French artist’s technical experimentalism. Bacon, too, felt the lure of working in three dimensions, judging from the Sylvester interviews, though unlike Degas he remained a sculptor manqué.61 Even taking into account the posthumously revealed sketches discussed earlier, Bacon barely drew and, according to Sylvester, was ‘forever asserting that he couldn’t draw’, but, interestingly, he was drawn to several artists renowned for their virtuoso draughtsmanship, Degas and Michelangelo as well as Giacometti and Seurat.62 Discernable here is an element of compensation or wish fulfilment in an artist who had never learnt to draw in the traditional sense, and who relied on inventive manipulations of paint to evoke the presence of forms in space. In other words, within the identification, there was also an attraction of opposites in Bacon’s response to Degas.

This essay assembles some evidence – and quite a lot of speculation – regarding what Bacon might have derived, throughout his career, from looking hard at works by Degas. Some of its juxtapositions of particular works may seem more persuasive than others, but it is hoped that the overall argument has demonstrated that there is a real continuity of sensibility between the two artists, and that Bacon’s documented admiration for Degas had profound, wide-ranging consequences for his art – on a par with his immersion in Picasso or Soutine. There is doubtless much more to be said about what he saw and valued in Degas, such as sexual connotations, or a darker side of the French artist implicit, too, in John Berger’s comments about his fascination with ‘the human capacity for martyrdom … The human quality Degas most admired was endurance’.63 On a broader front, finally, this essay has sought to indicate the benefits of treating Bacon as a singular but also regular artist, rather than as a kind of shaman or a charismatic bohemian who happened to paint. Regular artists, especially those of the highest distinction, find compelling provocation in other works of art, and Bacon was no exception: ‘to create something … is a sort of echo from one artist to another’. He may have been personally committed to alcohol, gambling and picking up teddy boys, but bouncing off great artists like Degas was ultimately far more significant for Bacon’s painting.