John House

What is interesting about Turner, Whistler and Monet together is that we see the different ways in which the Thames could be painted. For example, Whistler self-consciously created an aestheticised Thames, especially in his Nocturnes series, which Monet would pick up on several years later. Whistler was bouncing off a set of Victorian interpretations of London which saw it in very symbolic terms. Pollution is obviously one clear theme. It is not only the fact that it is a dirty river, there is moral pollution too. For example, the idea of the fallen woman – those who had committed suicide were usually depicted lying next to the river. For our three artists, the light was the key thing, but they viewed it in very different ways.

Patrick Keiller

I was struck by something at the beginning of your essay in the catalogue for the Tate show. You talk about Turner being dissatisfied by the daylight. I felt very familiar with that.

John House

With reference to the London paintings, you could say that Turner painted the sun, while Whistler went the other way and painted the night.

Patrick Keiller

And Monet?

John House

Monet loved the daylight. He liked as much of it as he could possibly get. But of course in Turner’s paintings you can sense he’s really saying: ‘I want to try to paint the sun, I want to do the transcendent.’ Which is not the same as how photographers or film-makers would deal with sunlight.

Patrick Keiller

I spent a lot of time filming the river when I was making London in 1994. I started at Teddington with the idea of working my way up to Tower Bridge, often filming both sides of each bridge, though by the time I reached Vauxhall I had already encountered most of the remaining bridges in other shots, in particular the view from Monet’s suite in the Savoy. I wanted to recover the river as a subject, and a space, rather as artists of this earlier period – Turner, Whistler and Monet – had depicted it.

Until London, which was the first film I made in colour, I had always thought it a difficult camera subject – the city’s light was so often hazy (I assumed as a result of pollution from the traffic), but with colour this was less of a problem. With the monochrome cinematography of earlier films, I tried to create an illusion of depth; to fake the stereoscopic effect, which I’ve since discovered was also a preoccupation of early filmmakers, particularly Cecil Hepworth. One encounters it especially in films from moving vehicles, such as the Lumière railway panoramas photographed by Alexandre Promio that I have been looking at recently. Filmmakers were aware of the popularity of the stereoscope and attempted to emulate it. In early 1990s London this seemed to be difficult, as it was in the 1890s because of the fog, which was so prevalent at the time.

John House

Well, it’s difficult in mist and haze, but in fact that is what drew Whistler and Monet to the place. They were fascinated by the flattening effect of this kind of light. Of course it was all part of the aestheticising of the image. And that really explains why both Whistler and Monet felt they were men of the fog. Monet said: ‘How could the English painters of the nineteenth century have painted its houses brick by brick? Without the fog, London would not be a beautiful city.’

Patrick Keiller

There were also a lot of visiting writers, from Dostoyevsky to Jack London, and some of them write very evocatively about the fog. When Apollinaire arrives in London in 1901, his description of the south London suburbs, seen from the train, is of ‘wounds bleeding in the fog’.

John House

Yes, there is very much a sense of two Londons in writers of that period, who give it a powerful symbolic geography. There is the fashionable West End, and then there is the East End depicted as a kind of exotic foreign country. There are certain recurrent rhetorical devices that people use, and which crop up in the guide books of the time, that constantly reiterate the same stereotypes about the East End – the classic example being the story of Jack the Ripper, although apparently the killings happened only on clear days.

Patrick Keiller

And looking at Booth’s poverty maps, quite a bit of east London doesn’t appear to conform to the stereotypes. In 1889, much of Bow is ‘middle class’, much of Stepney ‘good ordinary earnings’.

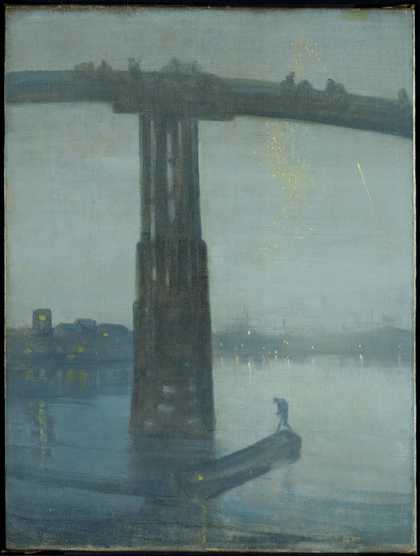

James McNeill Whistler

Nocturne: Blue and Silver - Chelsea (1871)

Tate

John House

In contrast, most artists were actively working against these stereotypes. Take Whistler’s picture Nocturne in Blue and Silver – Cremorne Lights 1872, for example. Cremorne Gardens in Chelsea is a very loaded site of a rather risqué place – a pleasure garden where people gathered at night. With its title, everybody would have known the associations. And his etchings of Docklands, which are detailed depictions of everyday life in the area, ignore the popular literary narratives of the day. They ignore the crime narrative, the sin narrative, in favour of these very coolly presented figures going about their daily business. When Whistler moved to Chelsea in 1863 his subject matter also moved – away from big shipping to just the occasional barge. In a sense he moved away from modern life itself, from action to these extremely still scenes.

Patrick Keiller

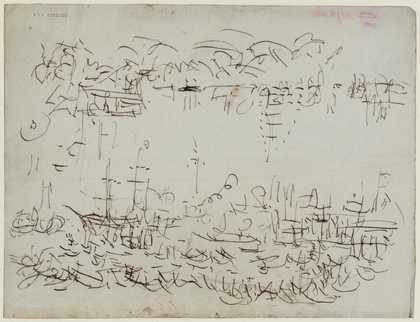

How does Turner deal with London?

John House

Turner’s river landscapes are history paintings in which there’s usually some sort of elemental statement – a significant effect or event. The most dramatic example obviously is The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, 16th October, 1834.

Patrick Keiller

But there’s often an element of fiction, isn’t there? With Turner, one feels there’s an act of transformation, which is to do with experience itself, or some other redemptive sentiment; a kind of ‘if only’ feeling.

John House

Yes, but that’s certainly not true with Monet. However, I would always want to see Monet’s London paintings as being more fictional than we give them credit for, because they are re-worked when he’s back at Giverny. I think there’s a danger of thinking about Monet paintings as being somehow transcriptions. It is worth remembering that he left London early in 1901 and it was another three years before he was ready to exhibit these works. He spent much longer working on them at home in Giverny, than he did in London. Monet talks about having an idea of what is London-like – ‘londonien’ – after he’s been sitting on the Savoy balcony for a few months.

Patrick Keiller

The painters were also responding to the changing nature of the city. A century ago, much of today’s suburban London had still to be built, but 100-year-old images of the centre often appear incongruously familiar. We have the idea that concepts of architectural and urban space changed radically after about 1907, but the pattern of central London’s fabric remained relatively static after about 1910, following a long period of quite major physical upheaval – the railways crossing the river, the construction of the embankments – that culminated with the completion of Kingsway and the Aldwych. This was also an interesting time in cinema, which around 1906–7 developed from being what the film historian Tom Gunning has called the ‘cinema of attractions’ – short films of between one to three minutes, mostly a single shot – to the edited narratives we know today. Many early films were street scenes, tram rides and other urban landscape subjects. The Lumière Brothers’ Alexandre Promio made a number of films in London in 1896 and again in 1897, when he went on to Liverpool and Ireland. One of the best known of these was taken from a boat passing downstream beneath Tower Bridge on a misty or foggy day. Two others depict the departure and return of The Thistle, a pleasure steamer, at what appears to be Pimlico Pier, opposite Nine Elms, where the gasworks is visible. These films were exhibited largely in entertainment venues. They were records of actuality, but even when photographing news events (ship launches, the Jubilee procession and so on) the film-makers weren’t exactly making news films in the later sense.

James McNeill Whistler

Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge (c.1872–5)

Tate

John House

But the painters don’t do entertainment. Nothing ever happens in Monet’s London series, for example. The nearest thing to anything happening is two trains crossing on Charing Cross Railway Bridge.

Patrick Keiller

I wonder to what extent the cinematographers saw themselves as artists, and if there was any crossover. Did Monet ever go to the cinema?

John House

I doubt it. He was living as an old man in Giverny by the time it arrived as a popular medium. However, there were still photographers who looked at the paintings. Alvin Langdon Coburn’s very self-contained London views of 1906 are absolutely straight out of Whistler. This sort of art photography of the Thames in a very Whistlerian mode actually begins before 1900. Twenty or 30 years earlier, photographers were addressing the question of whether they saw themselves as artists. Clearly, Whistlerian photography is the absolute vindication of photography as a form of fine art. You could say that there is an analogy between what you were saying about the very early films and Monet’s late series – the ongoing sets of views of the same subject. In his room at the Savoy with hundreds of canvases round him, he waits for the light to change. In the series you can see that he looks slightly to the left and slightly to the right of his view. There’s an act of framing that he is thinking about from the start.

Patrick Keiller

If you’re making a film, you are stuck with a single screen ratio – London was photographed in academy ratio, three by four. I’ve noticed that this is a format favoured by Turner, although less often by Monet.

John House

Yes, Monet’s paintings of the Houses of Parliament are much nearer square, but in fact the earlier pictures go the other way. Whistler, however, plays with formats. In the Tate show we have brought together two Whistler pictures – Brown and Silver: Old Battersea Bridge and Grey and Silver: Old Battersea Reach, both from 1863 – which we are presenting as what is effectively a filmic panorama. Joined together, you get his view out of his window in Battersea. They have this very wide sweep, with sailing boats and barges and the silhouettes of buildings on the other side of the river – you can even see the distant Crystal Palace.