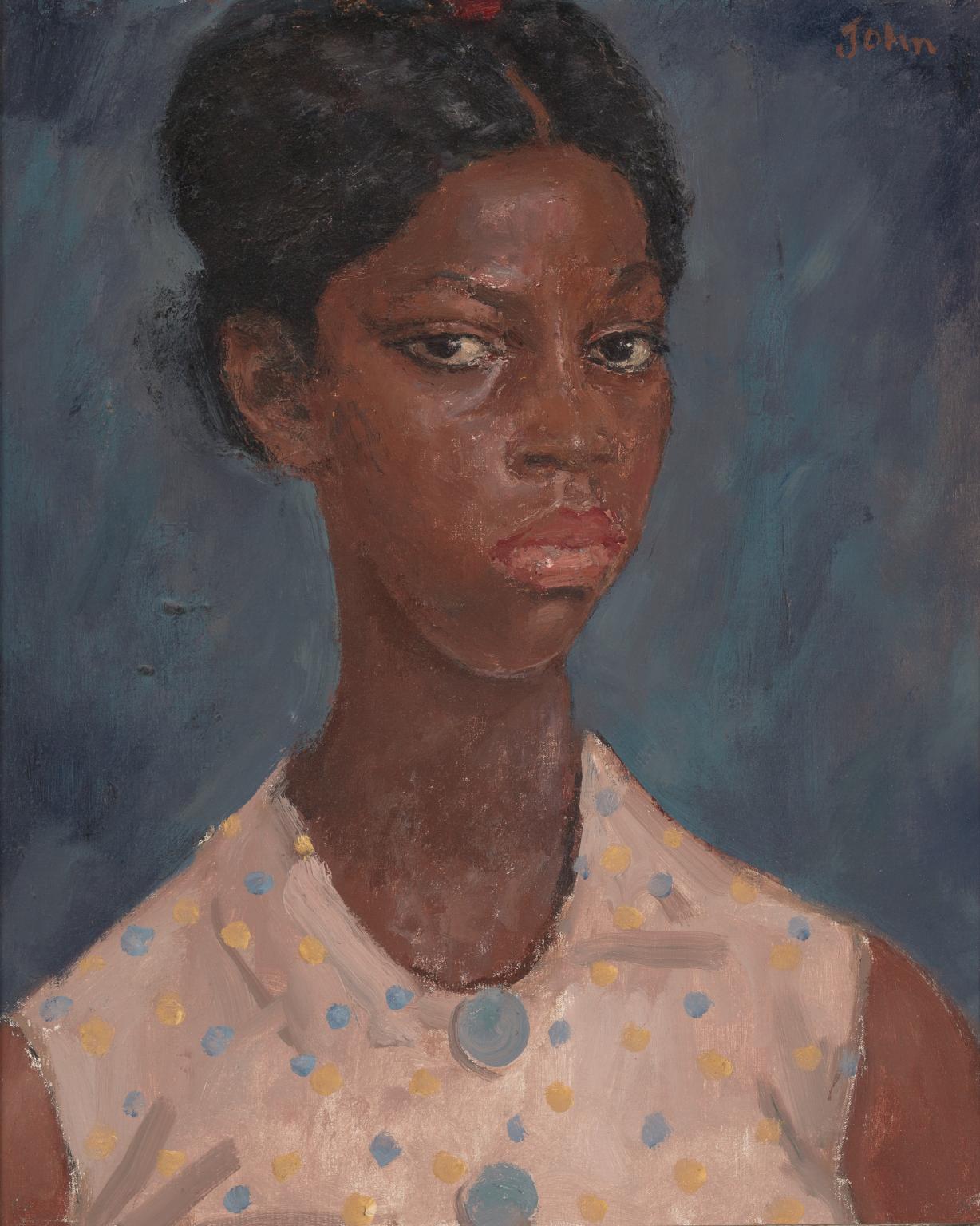

Augustus John OM, A Jamaican Girl 1937. Tate. © The estate of Augustus John. All Rights Reserved 2023 / Bridgeman Images.

Reality and Dreams 1920–1940

13 rooms in Historic and Early Modern British Art

British artists recalibrate their work in the aftermath of the First World War as they imagine how they could play a part in building a better society

The catastrophic impact of the war prompts many artists in Britain to change their work radically. Before the war, geometric and mechanised forms were seen as new, dynamic and exciting. However, in its aftermath, artists turn back to traditional genres such as portraiture, religious painting and landscapes. They term this mini revival as the ‘Return to Order’. More than revisiting old approaches though, this trend takes realism in new directions.

Younger generations react against pre-war values. They try to enjoy life to the fullest in the years known as the ‘Roaring Twenties’. Some artists portray women’s independence from traditional gendered roles. Others document the new diversity of London’s nightlife, as the city buzzes with new fashions, theatre productions and jazz brought from the United States by Black entertainers. Britain also enters a golden age of cinema and people flock to see new films.

However, this is also a time of depression, deflation and a steady decline of the British economy. By the mid-1920s, unemployment rises to over ten percent of the workforce in Britain. Declining industry leads to lower wages and increasingly bitter trades disputes. This culminates in a general strike in 1926. The Mass Observation research project documents working-class life during this period of economic decline. The Artists International Association leads artists’ opposition to a rise of fascism in Britain.

Surrealist artists are concerned with creating works influenced by dreams and fantasies. They create compositions that reject rationality and conscious thought through practices such as automatic drawing (drawing without thinking). The International Surrealist Exhibition in London in 1936 exposes younger British artists to the movement and encourages them to reimagine their work.

Frances Hodgkins, Flatford Mill 1930

Hodgkins was a New Zealander who came to Europe in 1901. Based mainly in Britain, she also spent time in Paris. She was a member of the Seven & Five Society. In the 1920s, its members developed an art that was both modern and returned to traditional motifs such as landscape and still life. A strong fascination with British landscape and traditions was evident. This is signalled, perhaps, by the fact that this scene was closely associated with John Constable who painted Flatford Mill in 1816.

Gallery label, September 2016

1/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Glyn Warren Philpot, Repose on the Flight into Egypt 1922

Glyn Philpot brings an unusual interpretation to the subject of the Holy Family resting on the flight into Egypt by incorporating mythological figures including a sphinx, a satyr and three centaurs. Philpot’s presentation of the mythological creatures alludes to pagan myths of unrestrained sexuality, and the implication is that this will be replaced by the new religion of Christianity. The Holy Family are seen sheltering against a huge sculpture from a ruined building, fragments of which appear in the background. This dream-like work has been interpreted as an attempt by Philpot to reconcile his adopted Catholicism and his sexual attraction to other men.

Gallery label, March 2018

2/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

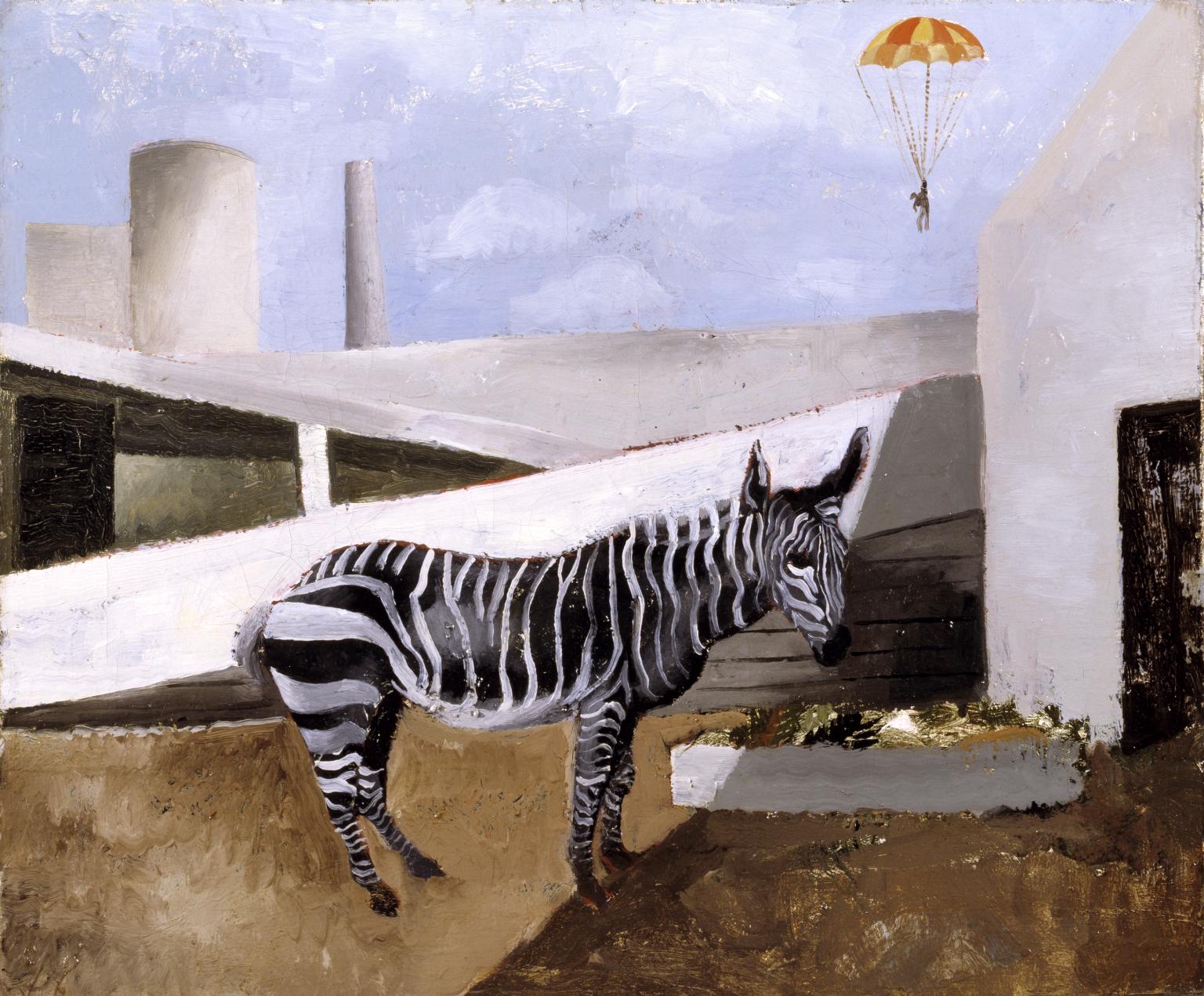

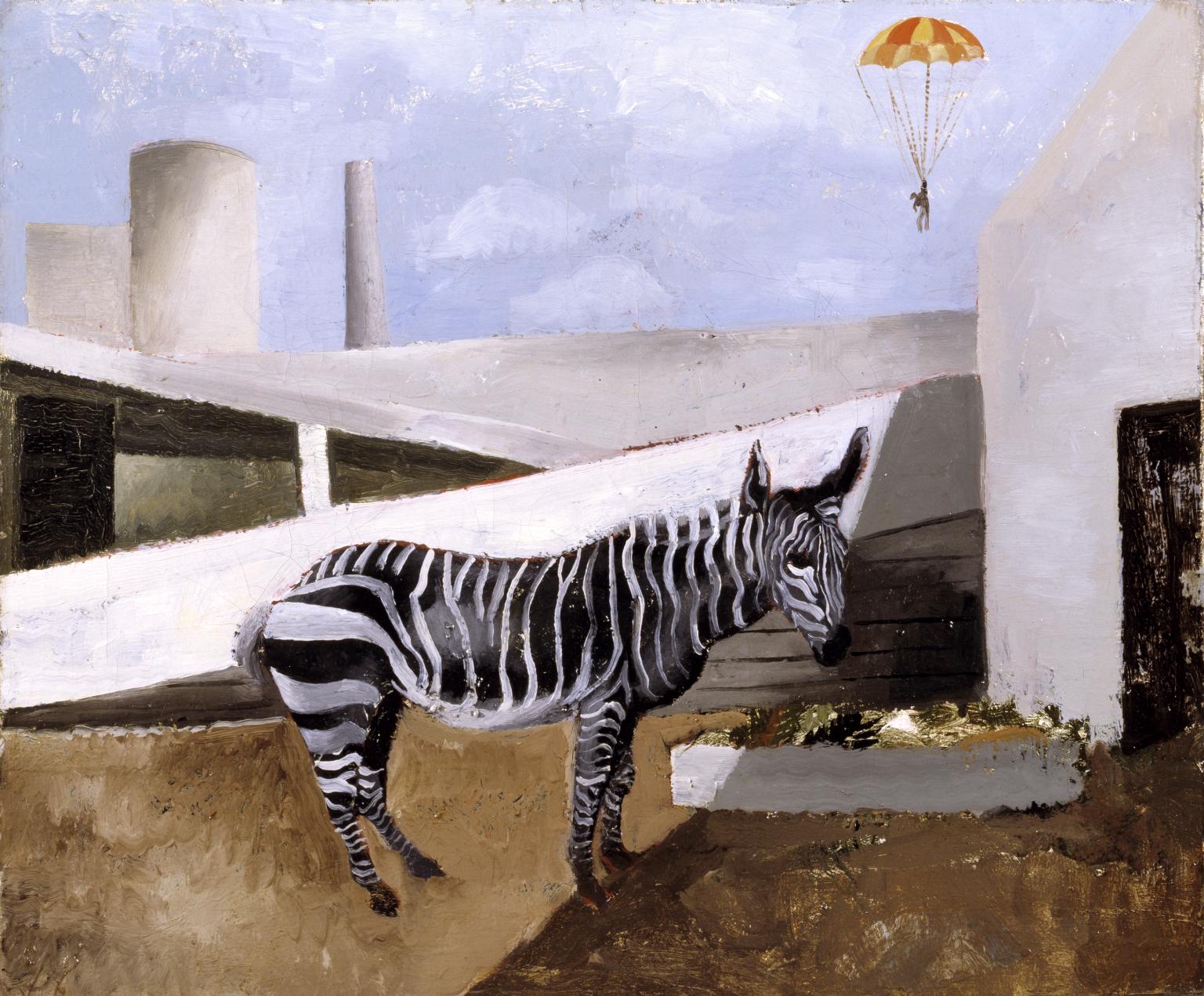

Christopher Wood, Zebra and Parachute 1930

A friend of the Surrealist poet René Crevel, Wood made a small number of paintings that seem to reflect the movement's harnessing of the unexpected. His placement of a zebra outside Le Corbusier’s modernist house, the Villa Savoie (then still under construction), suggests a deliberate confrontation of the surreal and the functional styles that were then dominant in Paris. The image is made more perplexing by the figure of the parachutist. This was one of Wood's last works: in a paranoid state, he fell under a train in August 1930.

Gallery label, July 2007

3/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Cliff Rowe, Street Scene Kentish Town c.1931

4/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

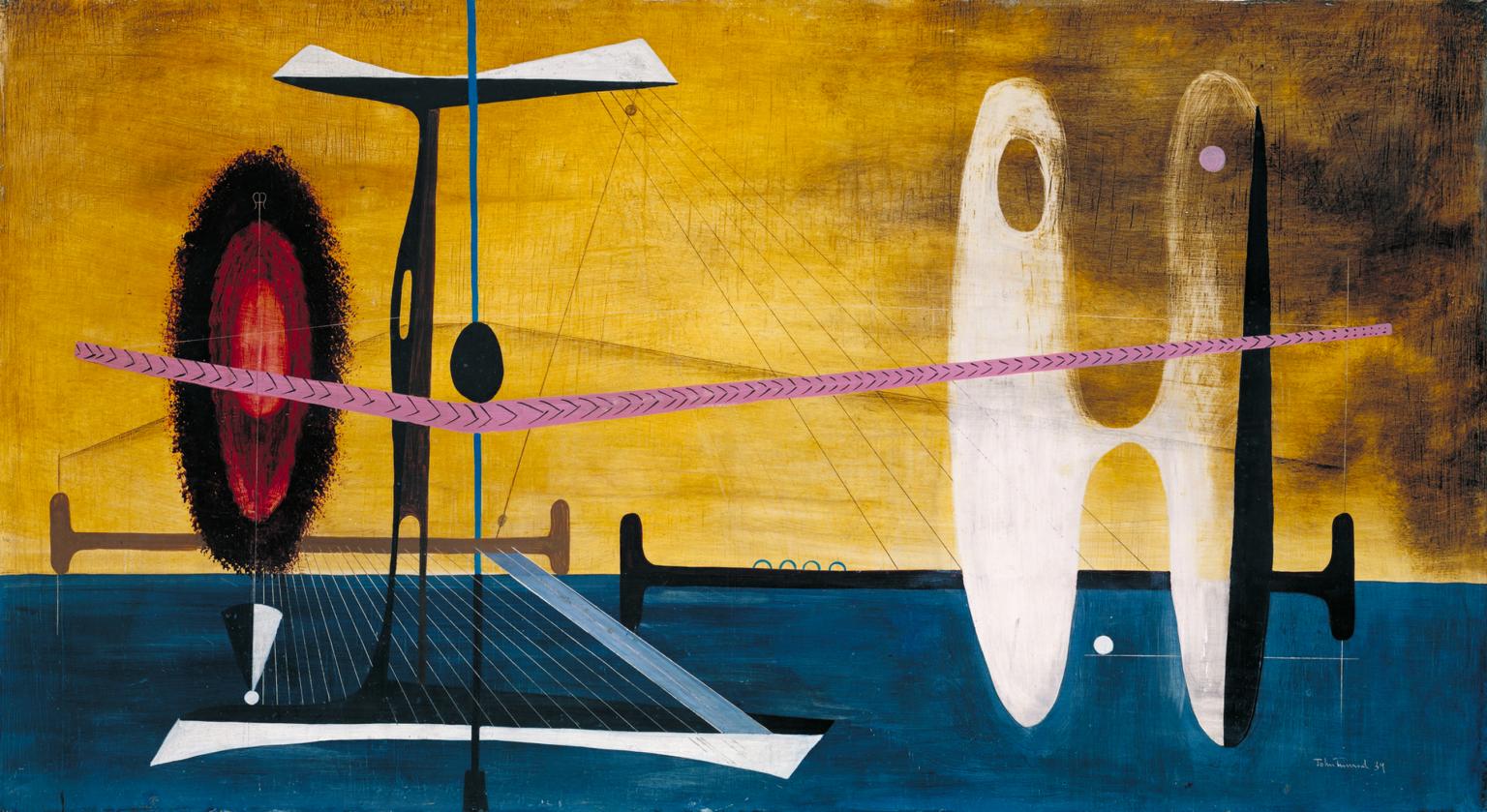

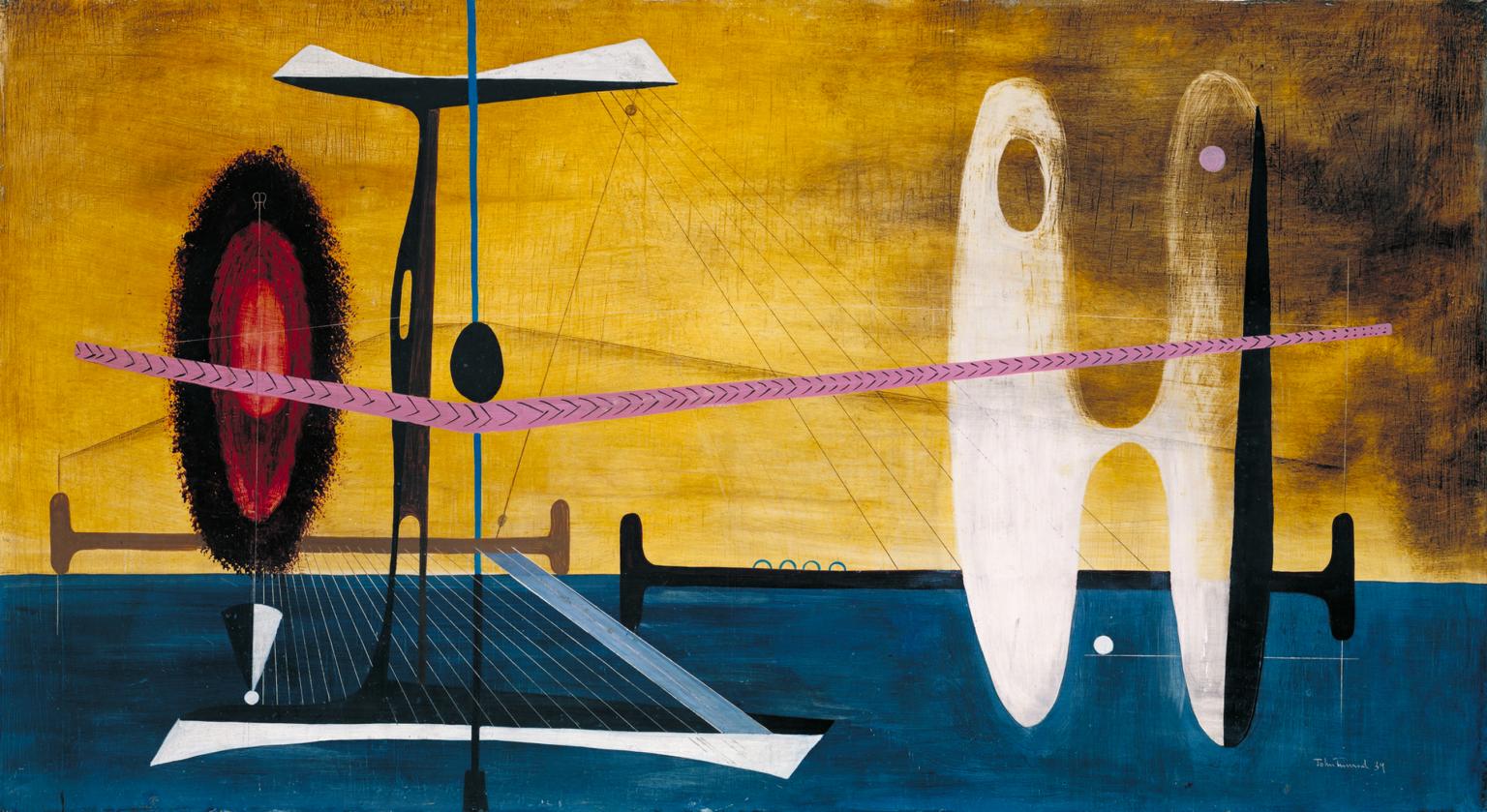

John Tunnard, Fulcrum 1939

An advocate of surrealism in Britain, Tunnard was interested in experimental techniques that summon an imaginative world. He developed a unique vision of quasi-mechanical structures in deep space that remain mysterious. Tunnard was taken up by the American collector Peggy Guggenheim and shown in her London gallery in 1939. The story goes that he crossed the private view to introduce himself to a prospective collector by turning three somersaults.

Gallery label, September 2016

5/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Grace Pailthorpe, April 20, 1940 (The Blazing Infant) 1940

6/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Peter László Peri, Rush Hour 1937

Rush Hour 1937 is a work in low relief that depicts men and women boarding a double-decker London bus which is full of seated passengers. They crowd around the pavement and ascend the spiral staircase at the back of the bus as the conductor looks on. The street scene also includes a cyclist passing the bus on the right-hand side and another bus further in the distance. The scene combines realism and abstraction in its precise observation of the actions of people in everyday situations set against the simplified rectangular shapes of the two buses. The work is executed in coloured concrete low-relief, the grey, blue and terracotta forms of the people and buses set against a pale grey background. Peri developed a method of modelling concrete directly rather than casting it; keeping it moist and malleable, he gradually built up his compositions using different colours of concrete. His use of concrete was both utilitarian and egalitarian and his work had a conscious political agenda intended to broaden the social reach of art by representing ordinary people and by appealing to a wide public.

7/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Henry Moore OM, CH, Girl 1931

From the mid-1920s Moore had advocated the abolition of the 'Greek ideal' in sculpture in favour of non-European sources, which he felt had much greater vitality. This work reveals his fascination with the Mesopotamian sculptures in the British Museum, especially solemn standing figures with clasped hands. He reviewed a book on Mesopotamian art for 'The Listener' in June 1935. Around 1931-2 Moore also turned his attention to the study of natural forms, such as shells, bones and pebbles. He then brought together his studies in natural forms with his admiration for non-European 'primitive' sculpture and began to introduce a rhythmic and non-naturalistic approach to the depiction of the human figure.

Gallery label, August 2004

8/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

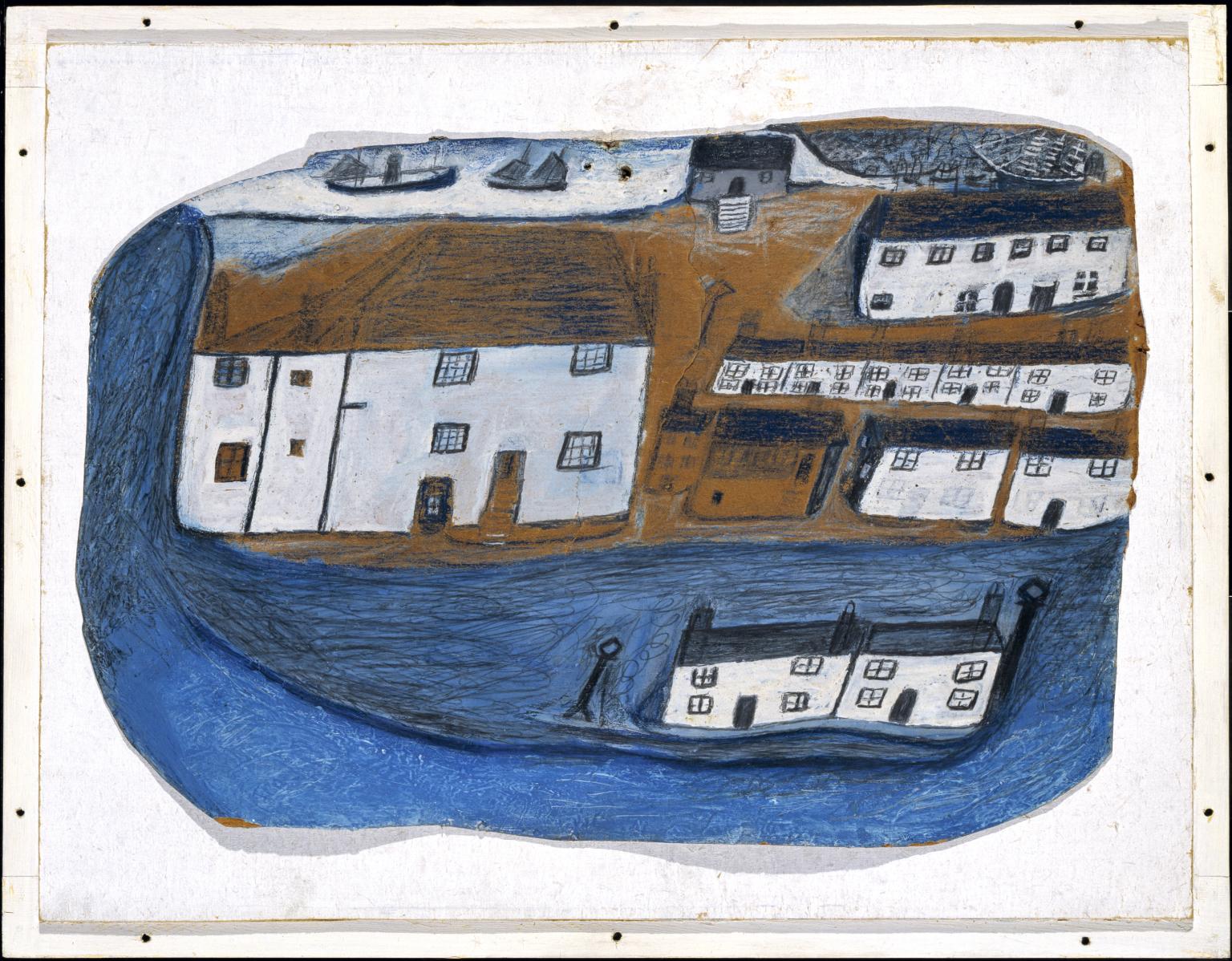

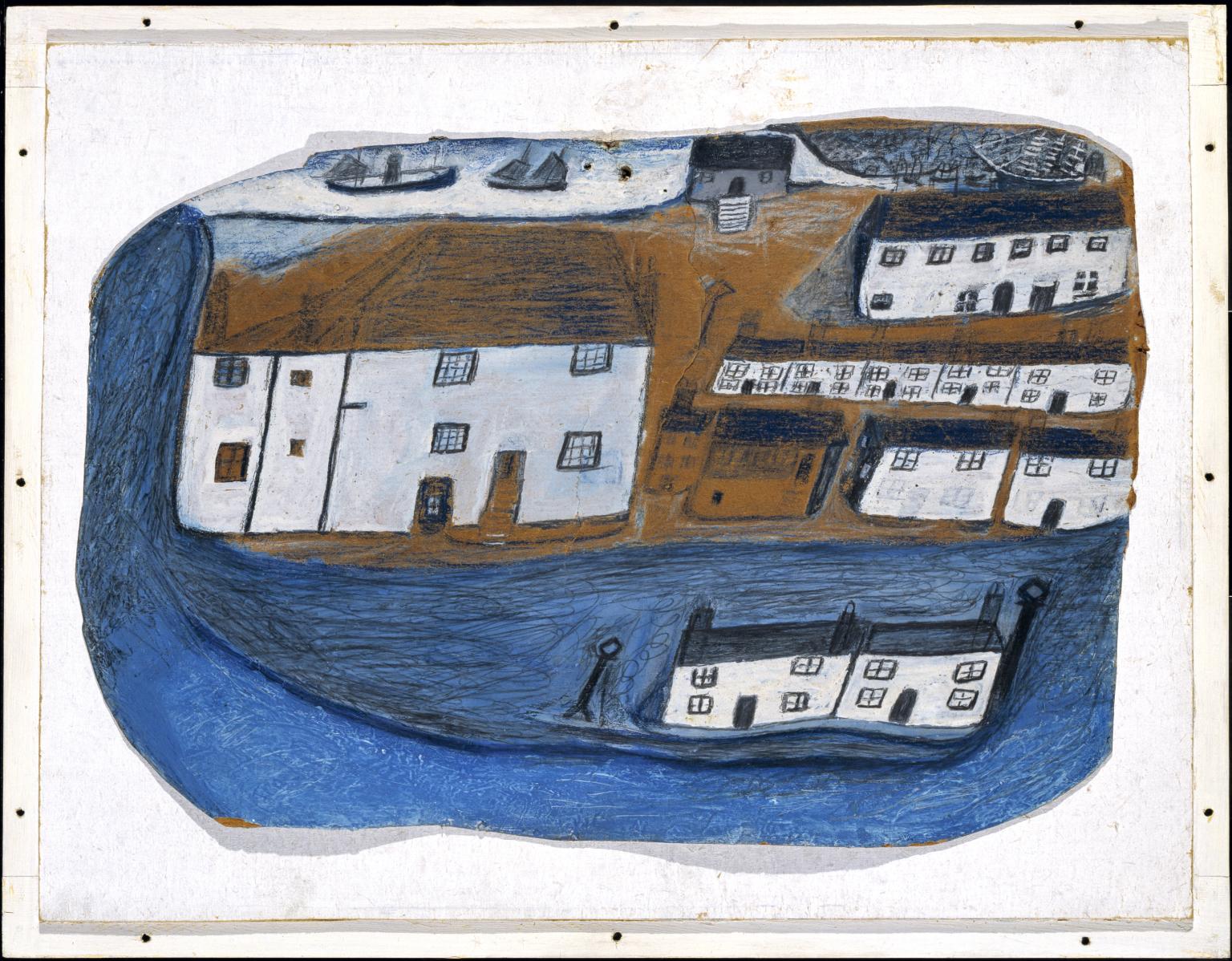

Alfred Wallis, St Ives c.1928

Wallis had worked as seaman, ice cream vendor and scrap merchant before he took up painting as a hobby in his retirement. He lived in St Ives, Cornwall, a fishing community and artists’ colony. There he encountered the painters Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood and his work was shown with theirs in London. Most of his paintings are of his local environment or of places and events remembered from his past.

Gallery label, July 2017

9/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

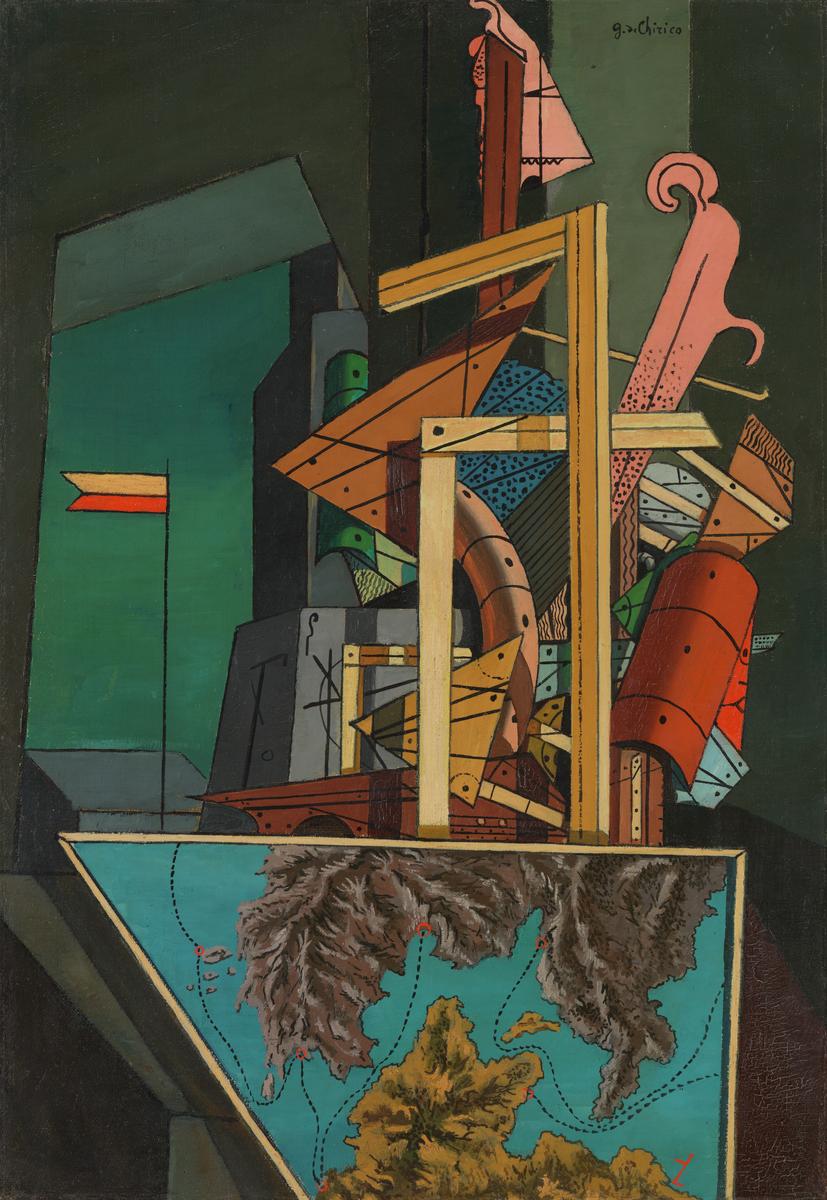

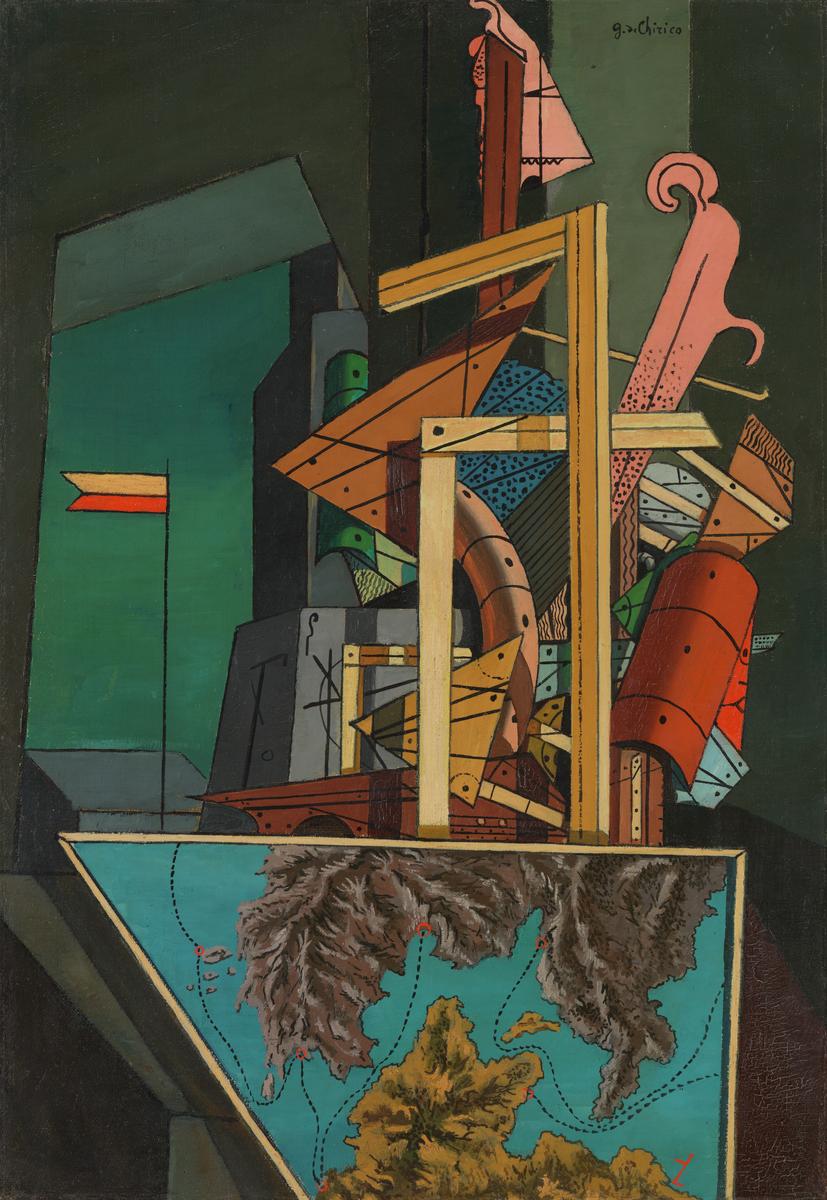

Giorgio de Chirico, The Melancholy of Departure 1916

De Chirico painted The Melancholy of Departure after he returned from Paris to Italy to serve in the First World War. The window and the map with a traced route evoke ideas of travel, suggesting escape from a cluttered, claustrophobic studio. Even as a child in Greece, de Chirico felt detached from his surroundings and identified with the voyaging Argonauts of Greek mythology. He imagined their journey across ‘measureless oceans’, an atmosphere which the Paris Surrealists saw as anticipating their own concerns.

Gallery label, January 2022

10/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Sir Stanley Spencer, The Woolshop 1939

This work was inspired by Spencer’s visit to a wool shop with his friend Daphne Charlton while staying in rural Gloucestershire at the end of the 1930s. It originates in a series of drawings of Charlton and himself and was made in the wake of his turbulent relationship with his second wife, Patricia Preece, and after leaving his former home at Cookham in Berkshire. Spencer later recalled that ‘Stonehouse had several of these small local shops such as I remembered years ago in Cookham. The Cookham ones must have emigrated there.’

Gallery label, November 2016

11/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Nancy Cunard, Negro anthology Date not known

12/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

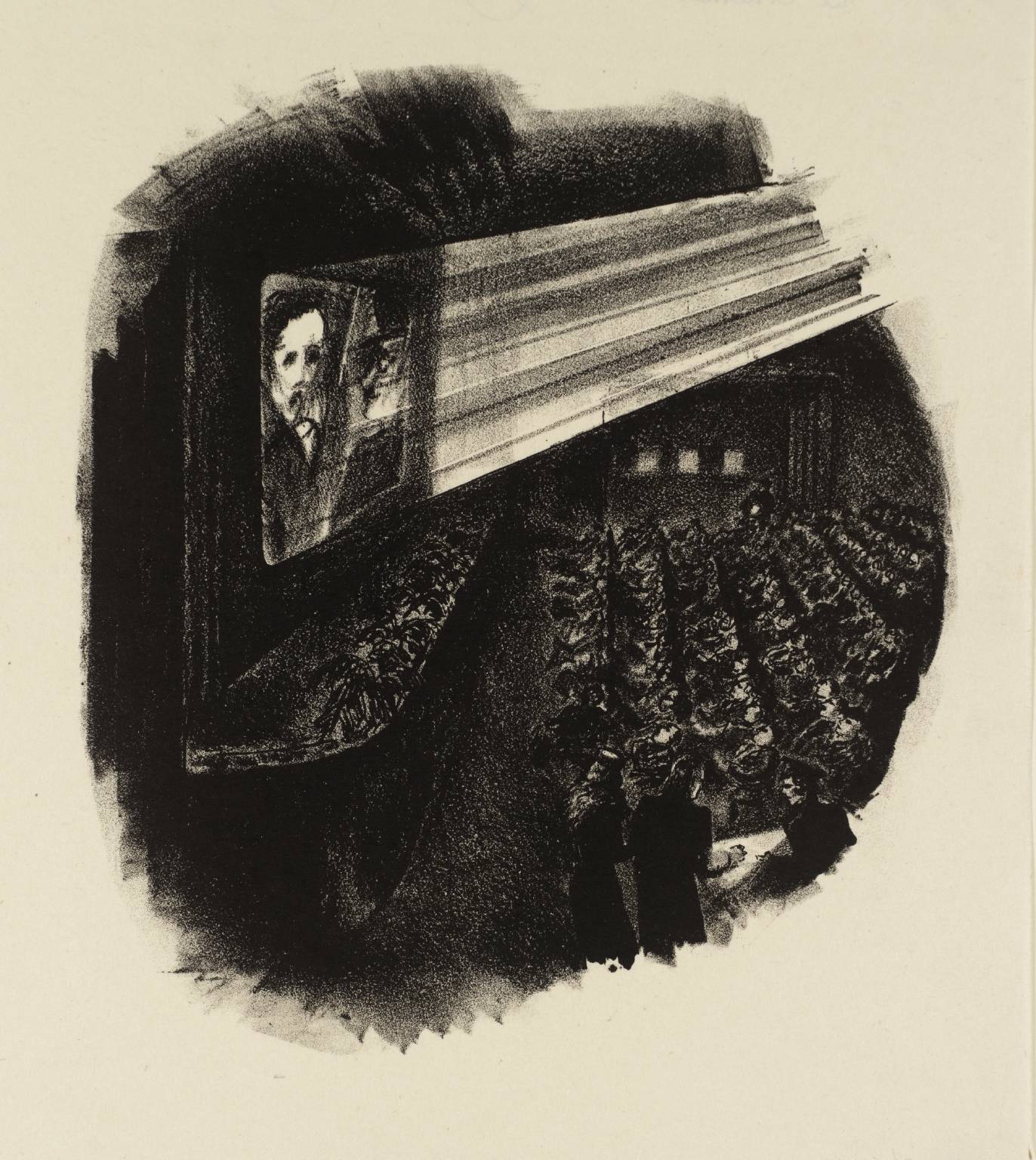

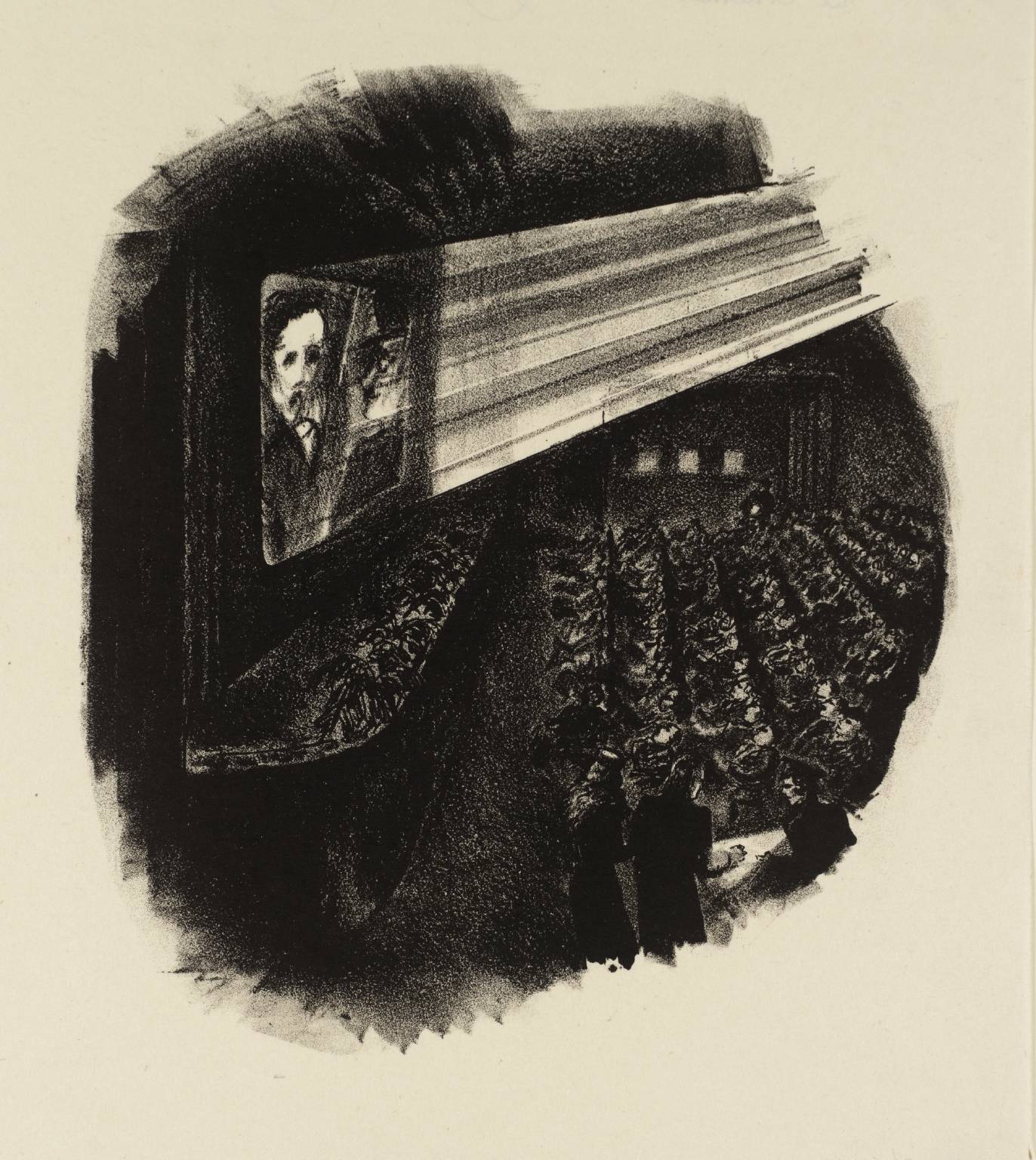

James Boswell, The Cinema 1939

When Boswell joined the Communist Party in 1932 he gave up painting and began to produce graphics for mass reproduction. The prints shown here were made as a result of the many evenings and weekends that he spent exploring the streets and pubs of working-class London, especially in Camden where he lived.

Boswell was a founder member of the Artists International Association. This group of artists and designers was formed in 1933 in response to the increasing threat of Fascism and the economic crisis in Britain.

Gallery label, September 2004

13/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Walter Richard Sickert, Variation on Peggy 1934–5

Sickert loved the theatre. He had admired the actress Peggy Ashcroft from one of her earliest stage appearances, as Desdemona in Shakespeare's tragedy Othello in 1930. This portrait was painted when Sickert was in his seventies; at this stage he often chose his subjects from newspaper images, in this case a photograph from the Radio Times of the actress on holiday in Venice. The painting's dry, grainy texture, and non-naturalistic, shadowless colouring puts a distance between background, figure and viewer. This painting combines two of Sickert's favourite themes: Venice and theatre.

Gallery label, August 2004

14/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Ceri Richards, Two Females 1937–8

The International Surrealist Exhibition was held at the Burlington Galleries in the summer of 1936, and for a brief moment, in the words of André Breton, London was ‘the centre of the Surrealist universe’. Richards exhibition gave him an opportunity to study important works by Ernst, Picasso and Miro, among others. Subsequently a pronounced erotic sensibility became apparent in Richards’s own loosely surreal work. Two representations of the female form are contrasted in this relief. On the right, virginal, though budding and seductive, and on the left, fulsome and latently sexual.

Gallery label, September 2016

15/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

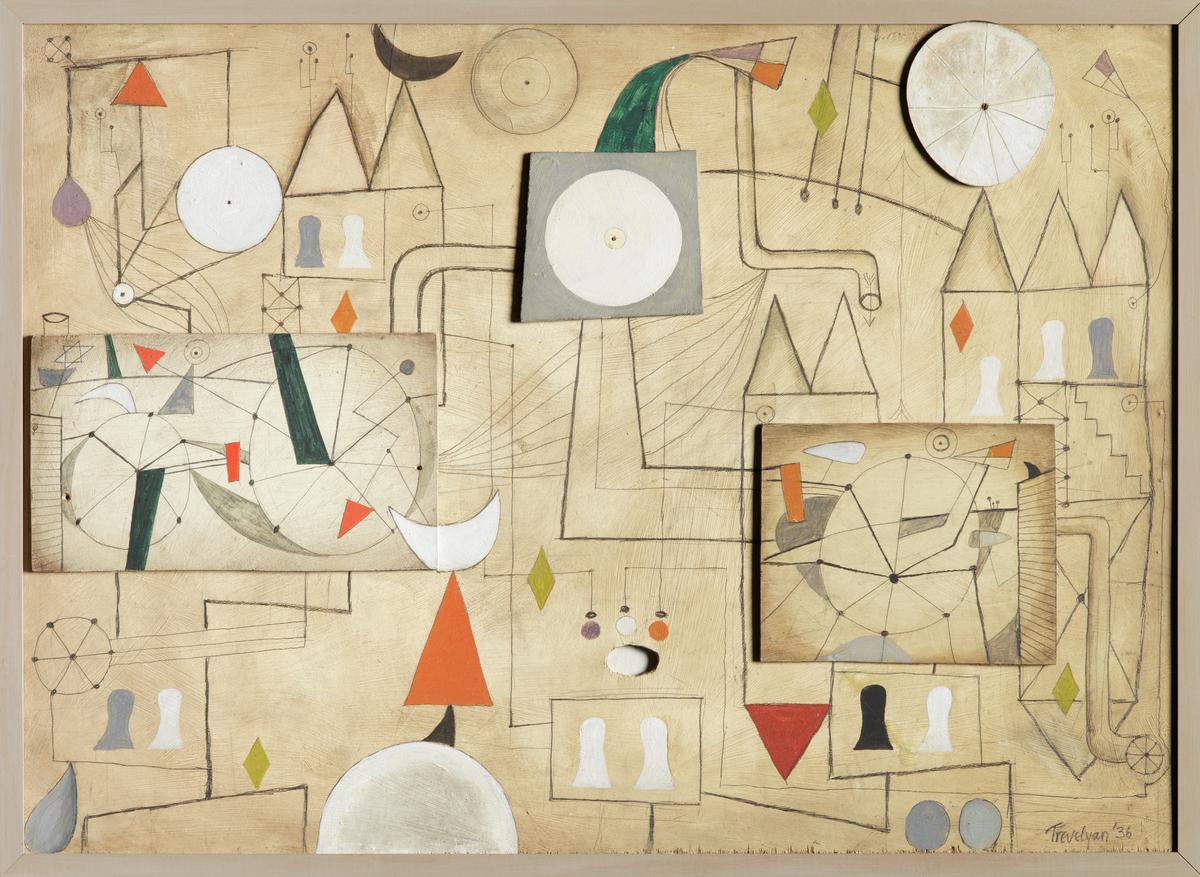

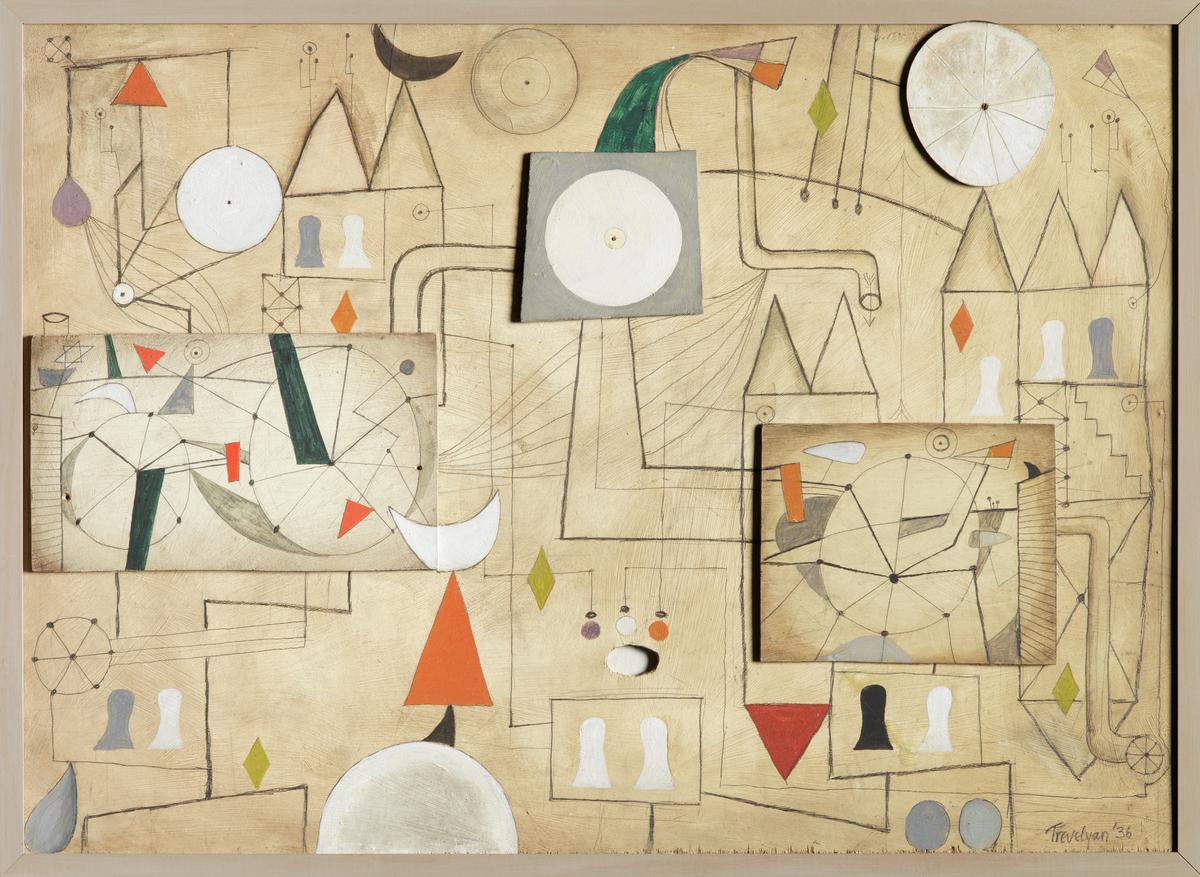

Julian Trevelyan, A Symposium 1936

Trevelyan became interested in Surrealism while at Cambridge, and came to know many of the movement’s leading artists when he lived in Paris in 1931-4. Influenced by Klee and encouraged by his friendship with Miró and Calder, he gradually developed his own mode of abstract Surrealism. In A Symposium Trevelyan combined painting and carving and attached parts to the wooden panel. He later recalled: ‘I had invented a sort of mythology of cities, of fragile structures carrying here and there a few waif-like inhabitants.’

Gallery label, December 2005

16/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Graham Bell, Dover Front 1938

Bell painted this picture on a trip to Dover in 1938 to fulfill a commission for the International Business Machines Corporation. The finely-observed detail of the hotel on the left, the chalk white cliffs and castle ramparts is typical of the realism of the Euston Road School, with which Bell was closely involved.

Although the artist painted on the spot, he may have used the photograph shown to the left to work on the details in his studio.

Gallery label, September 2004

17/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

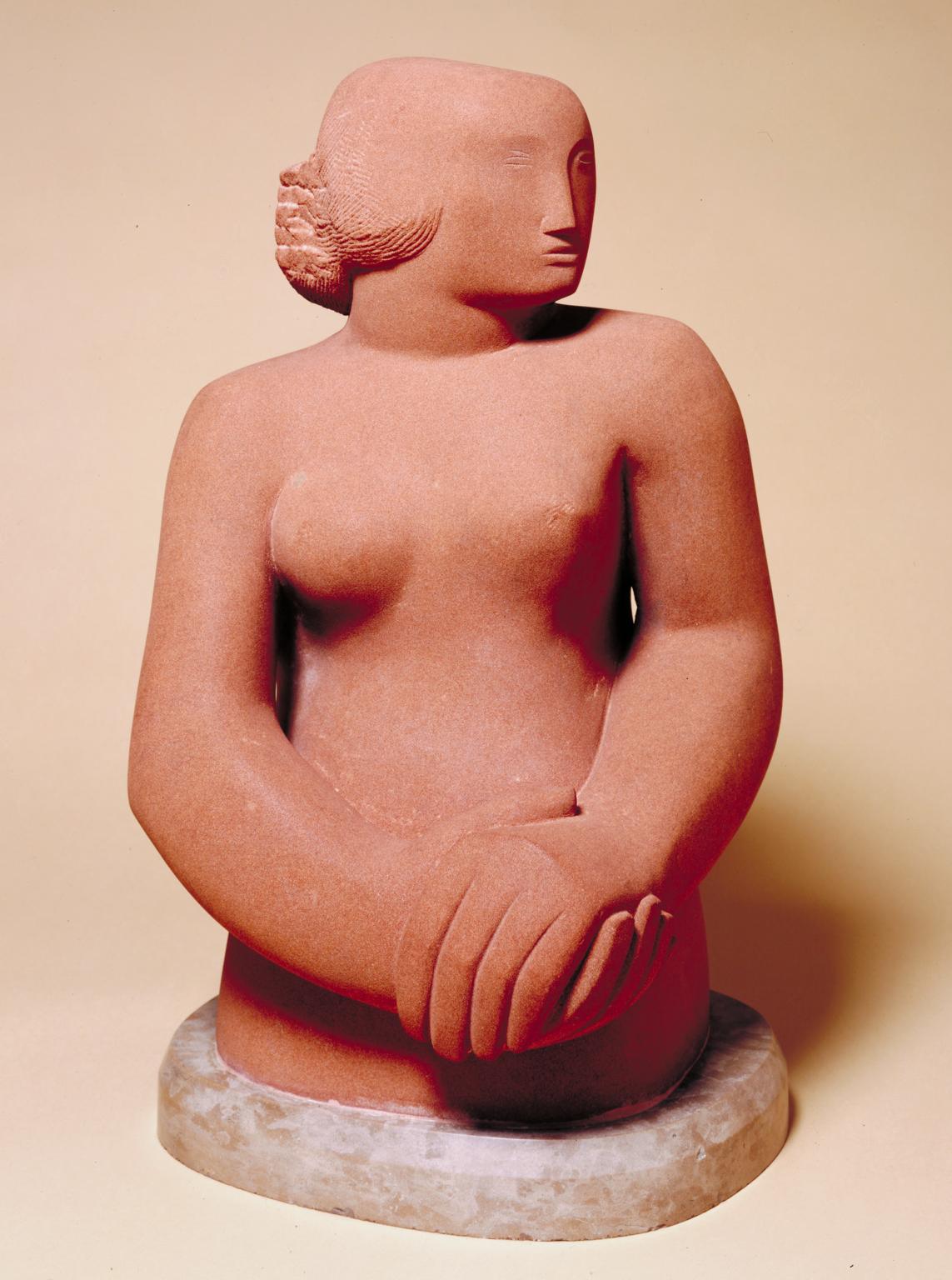

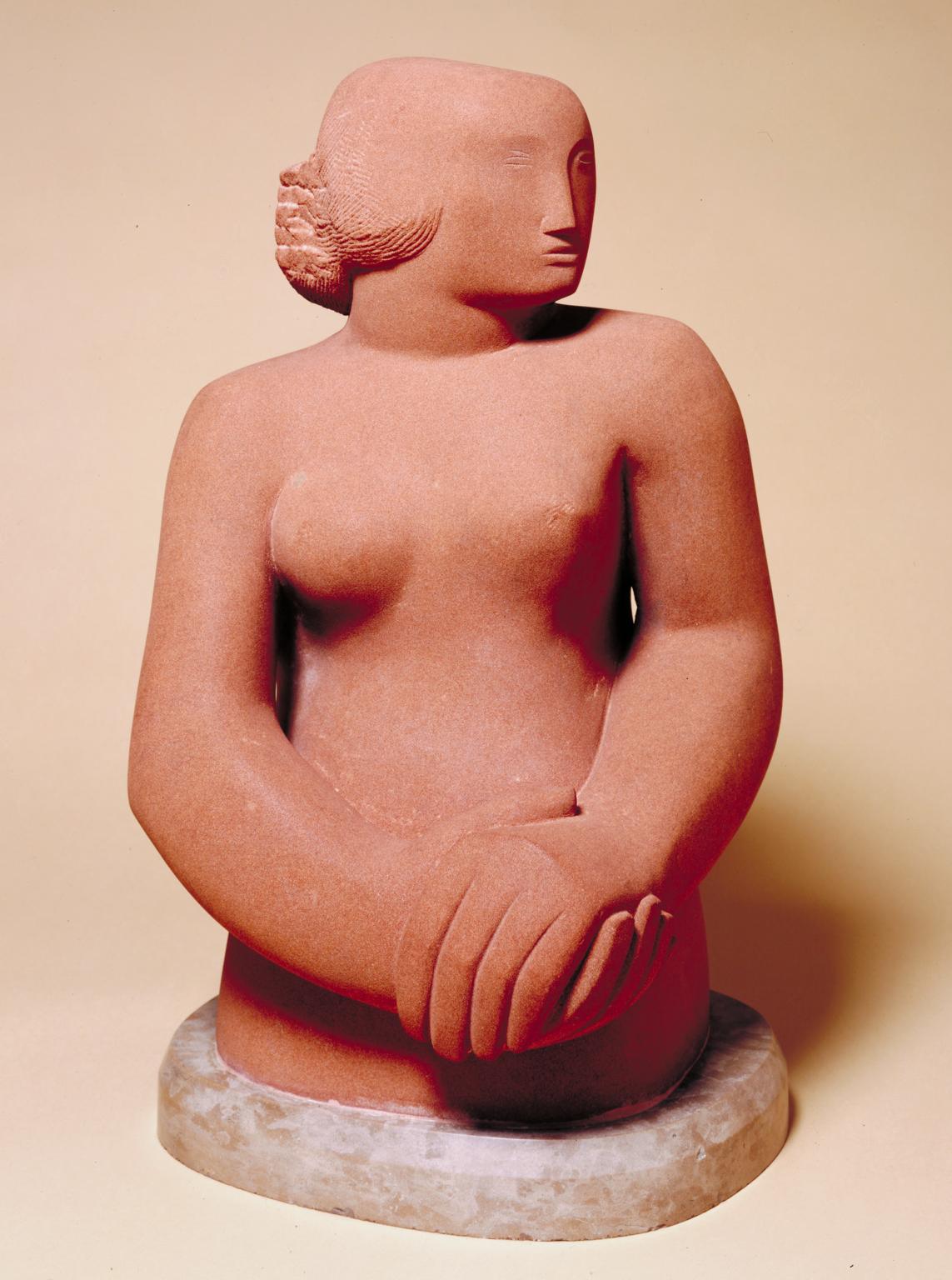

Dame Barbara Hepworth, Figure of a Woman 1929–30

Hepworth was one of a number of sculptors who returned to the handcraft of carving. The resulting immediacy of the artist’s relationship to her material was crucial. She described her process as an ‘effort to find a personal accord with the stones...I was fascinated by the kind of form that grew out of each sculpture, and by the kind of form that grew out of achieving a personal harmony with the material’.Like others, she sourced a wide range of indigenous British stones. This figure is made of Corsehill stone, a red sandstone quarried in Dumfriesshire.

Gallery label, July 2007

18/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Frank Dobson, The Man Child 1921

Dobson trained as both a painter and sculptor, but concentrated on sculpture after active service in the First World War. Like many of his contemporaries, he found inspiration for his work in the ethnographic collections of the British Museum. He particularly admired carvings from the Congo in Africa. Such interest in what had been considered ‘less civilised’ cultures became more widespread after the ‘sophisticated’ destruction of the war.Here, in the wake of conflict, Dobson returns to fundamental human relationships. The manchild of the title melds with two female figures who seem to embody maternal protection expressing both joy and fear for the new life.

Gallery label, July 2007

19/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

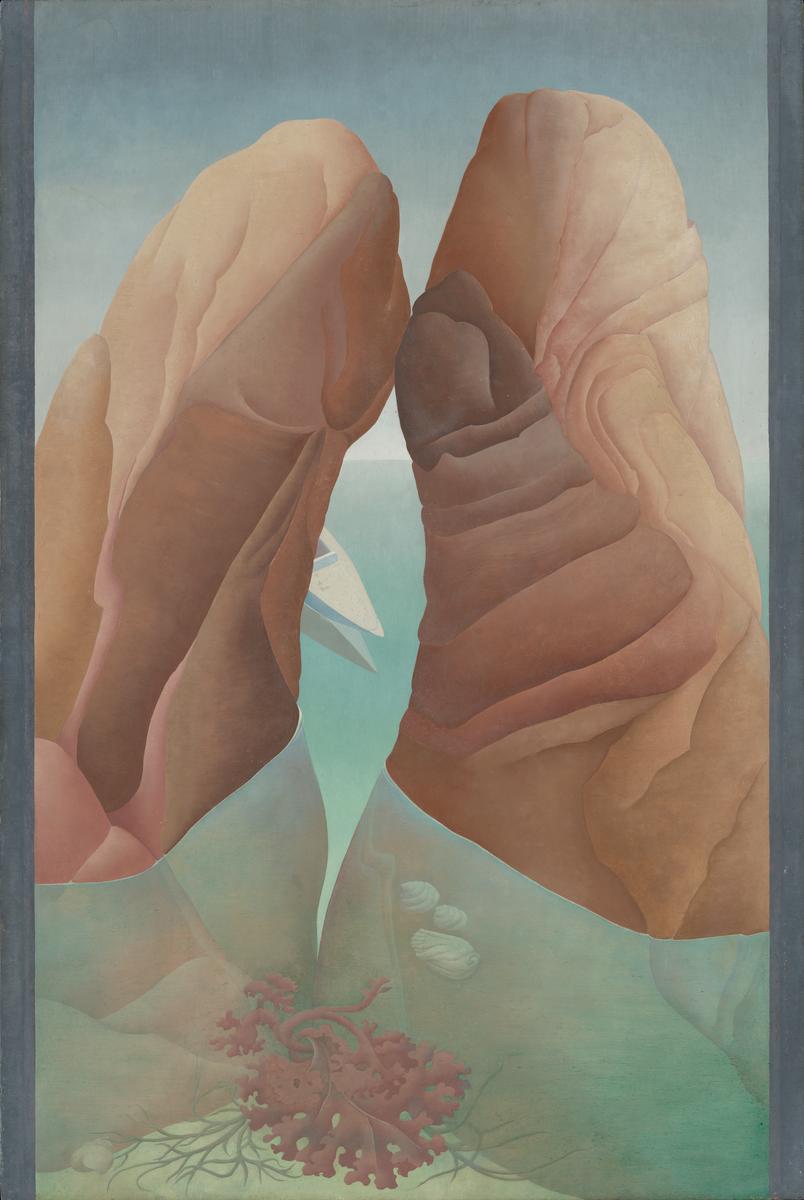

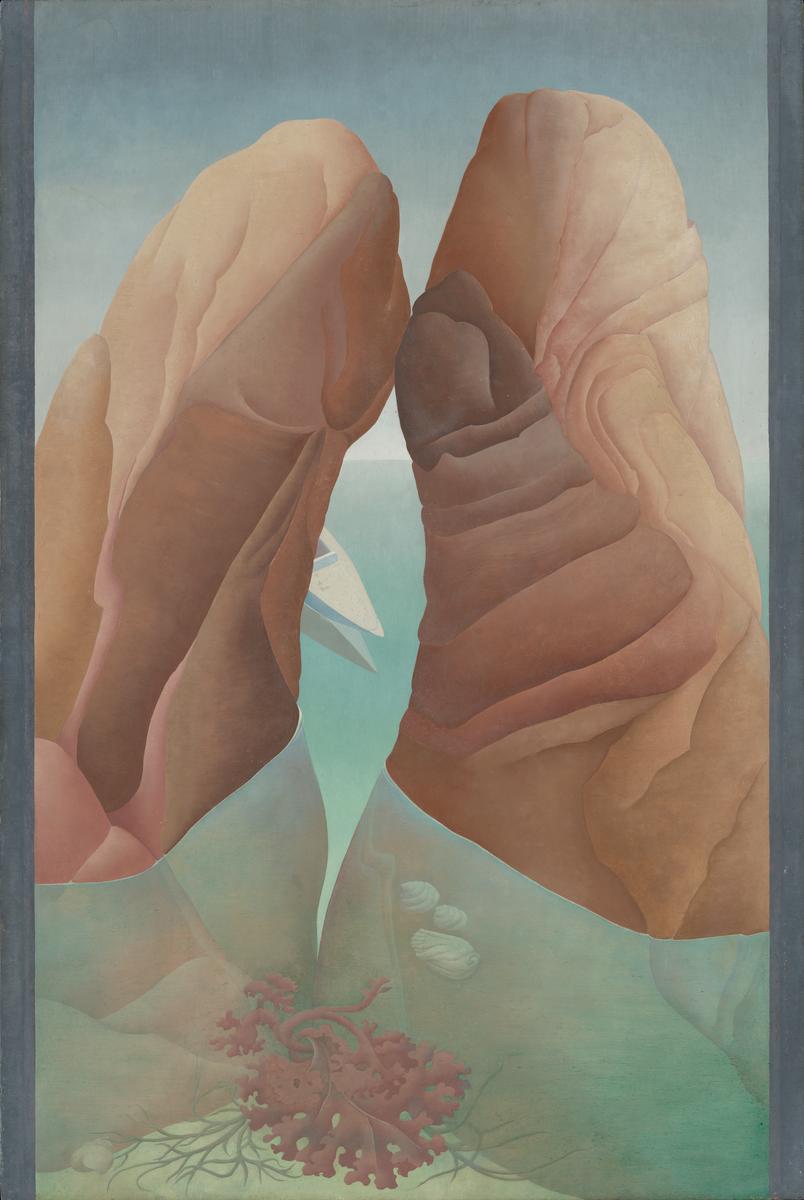

Ithell Colquhoun, Scylla 1938

The title of this work refers to the female monster who, according to ancient Greek mythology, inhabited a narrow channel of water and fed on passing sailors. Colquhoun explained that the image could be understood in two ways, both as a seascape and as an image of her own body. ‘It was suggested by what I could see of myself in a bath…it is thus a pictorial pun, or double-image’. The rock formations can also be seen as knees, with seaweed in place of pubic hair. This work was painted at a time when Colquhoun was exploring surrealist ideas such as the double image.

Gallery label, January 2019

20/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Sir William Coldstream, On the Map 1937

In this picture Coldstream shows fellow-artist Graham Bell standing holding a map, and his friend Igor Anrep sitting on the ground. Seen from behind, they look out across the landscape, apparently unaware of the painter’s presence. This conceit recalls such paintings as Degas’s Femme à sa Toilette, which Coldstream had praised for its ‘unbiased observation’. Such observation was to be a fundamental part of his painting from 1937 onwards.

Gallery label, September 2004

21/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Humphrey Jennings, Swiss Roll 1939

22/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Marie-Louise Von Motesiczky, Portrait of a Russian Student 1927

A young Russian student sits with raised hands and an uneasy expression. Marie-Louise von Motesiczky amplifies this tension through her use of muted colours and sharp contours that emphasise his angular features. The sitter’s identity is unknown, though Motesiczky may have met him through her brother’s links with Russian scholars. This painting reflects her early engagement with the German Neue Sachlichkeit movement, whose artists sought to capture the harsh realities of modern life.

Gallery label, October 2025

23/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

L.S. Lowry, Coming Out of School 1927

Like many of Lowry's pictures this is not a depiction of a particular place, but is based on recollections of a school seen in Lancashire. Lowry's combination of observation and imaginative power often produced images which capture a deeply felt experience of place, with which others could identify. For example, in 1939 John Rothenstein, then Director of the Tate Gallery, visited Lowry's first solo exhibition in London and later wrote: 'I stood in the gallery marvelling at the accuracy of the mirror that this to me unknown painter had held up to the bleakness, the obsolete shabbiness, the grimy fogboundness, the grimness of northern industrial England.' This work was then purchased by the Trustees.

Gallery label, April 1994

24/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

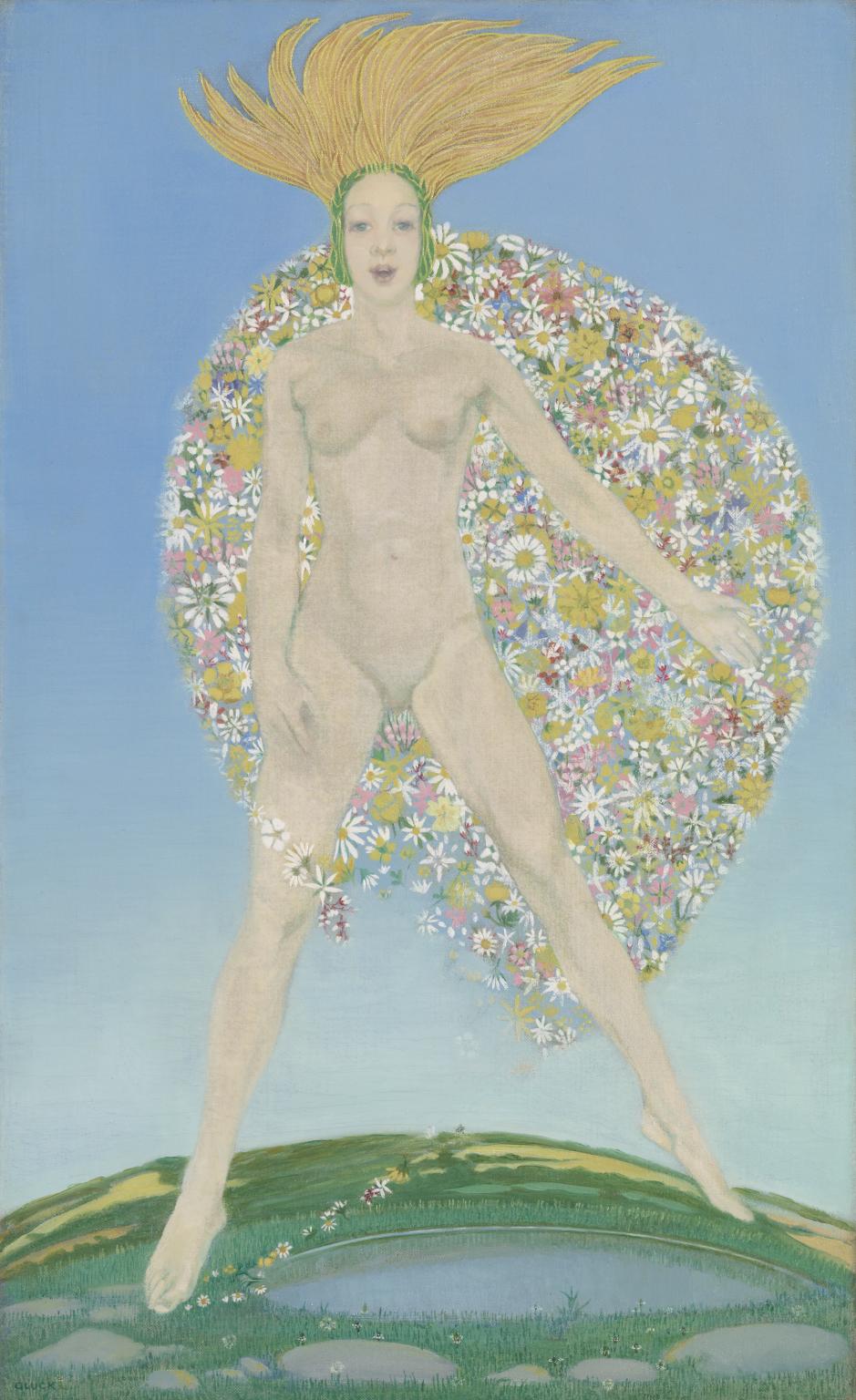

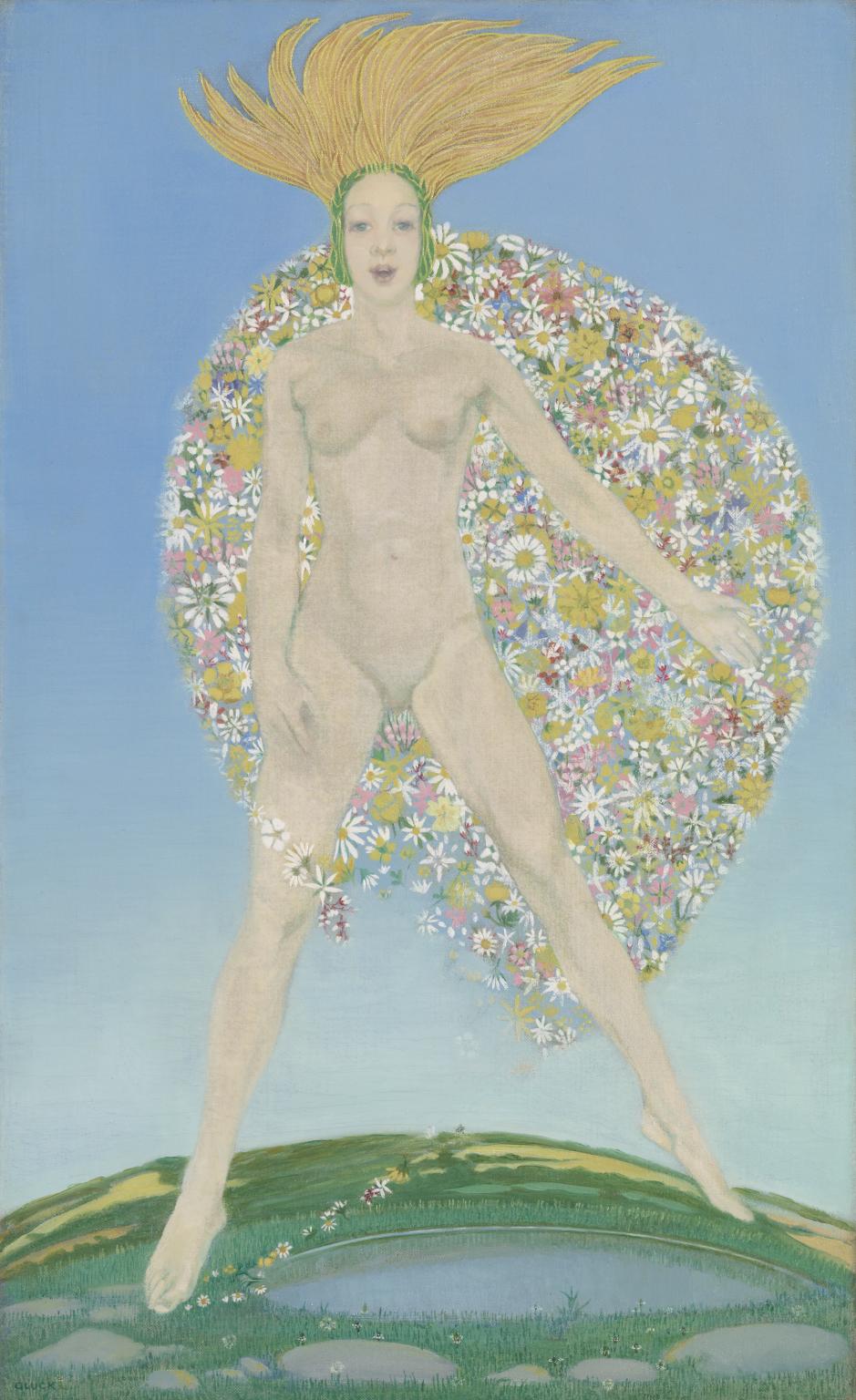

Gluck, Flora’s Cloak c.1923

Flora’s Cloak c.1923 is a portrait-format oil painting in the centre of which is a full-length figure of a nude young woman set on a pale blue ground. The figure’s legs and feet are pointed towards the lower corners of the canvas, so that she seems to be lightly floating in space. Her right arm hangs down and rests in front of her right thigh, while her left extends out from her core at forty-five degrees, with her palm open to the viewer. The geometrical spacing of her limbs recalls the form of Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man c.1490 (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice). Her nude figure is youthful but toned, with pale pink skin, and she wears a headdress reminiscent of straw or yellow flames attached to a green band framing her face. Her face is also youthful, with blue eyes and an open expression of raised eyelids and a slightly parted mouth. Behind her back and outstretched left hand is a billowing cloak of small spring flowers, including daisies painted in white and light green, with others rendered with darker green stems, and petals in light pink, and more occasional touches of deep red, light blue and purple. Like the figure, these flowers seem to hover or to move slowly in the air; together they form a rounded shape with a definite edge, cloaking her back, as well as a single trail that circles loosely as a narrow band of white flowers around her right thigh.The light blue ground slightly pales towards the figure’s feet and towards the centre of the composition, creating the impression of a portion of an airy cloudless sky on a bright day. At the figure’s base is a top-section of a rounded globe or mound of earth, covering approximately the painting’s lower fifth, which extends to the right, left and lower edges of the composition. In the foreground of this earth are some wide rounded pebbles, varying in size, before a circular pool of water, all set within a field of short green grass. Behind this a more distant landscape of yellow and green fields is visible. The pool is described as a reflection of blue sky and a rim of reflected green grass. The figure’s toes extend towards this earthly surface and her right foot appears to touch lightly the grassy bank. In this area a trail of smaller flowers has been painted in a small circle near her foot and then receding towards the distant earth. This might suggest that the figure, with her cloak of flowers, has brought them to the earth with her presence or touch.The painting’s title, Flora’s Cloak, refers to the Roman mythological character Flora, goddess of flowers and spring and symbol of fertility, youth and the renewal of life. Gluck’s treatment of this theme in this way particularly recalls the figure of the same character in Sandro Botticelli’s Primavera c.1470–80 (Uffizi Gallery, Florence), who looks to the viewer while scattering flowers over the ground, clothed in a billowing floral grown. Flora’s Cloak has also previously been referred to as ‘Primavera’. Botticelli’s example would have been well-known to Gluck and available in reproduction, as would also have been his full-length female nude in The Birth of Venus c.mid-1480s (Uffizi Gallery, Florence). Both Gluck and Botticelli’s paintings are allegorical visual expressions based on the personification of Spring. While Botticelli’s larger composition has been described as a depiction of the progress of the spring season over time, Gluck’s depiction catches the goddess at an extended moment of arrival or reign. In one textual description of the myth by Ovid, it is described how a naked wood nymph attracted the first wind of Spring, Zephyr; she was ravished and flowers sprang from her mouth, transforming her into Flora, the goddess of flowers. In this source the reader is told that ‘till then the earth had been but of one colour’, namely green (Ovid, Fasti, Book 5, 2 May, original 8 AD, trans. James G. Frazer, 1931). Flora’s Cloak is thought to be the only painting by Gluck of a nude figure. It was painted during the artist’s late twenties, after Gluck had returned to north London (where the artist was born, to an affluent Jewish family) following a close attachment to the landscape and artistic scene of West Cornwall. During the early 1920s Gluck lived and worked in London, first living in a flat in Finchley Road and working from a two-room studio in Earl’s Court; from 1926 the artist owned Bolton House in Hampstead, which had its own studio. Throughout Gluck spent summers in Lamorna, Cornwall, and continued an association with the Newlyn School of Painters. In the countryside Gluck was especially struck by the effect of light upon the sky and landscape, writing later how ‘a landscape is chameleon to the light’ (Gluck, ‘Notes on Landscape Painting’, undated [1940], quoted in Souhami 1988, p.42). A work comparable to Flora’s Cloak, as a symbolic expression of the wonder of the natural world, is a landscape based on Cornwall showing broad beams of light emanating from the sky (Pheobus Triumphant c.1920, private collection). Flora’s Cloak was included in Gluck’s first solo exhibition, at the Dorien Leigh Galleries in South Kensington in 1924. A show of fifty-seven pictures that proved a commercial success, this led to a second solo exhibition two years later, called Stage and Country, at the Fine Art Society, London.Gluck continued to exhibit with the Fine Art Society. In 1932 Gluck designed and patented ‘the Gluck Frame’, a three-stepped frame painted the same colour as the wall and intended to incorporate the picture into the wall visually, creating greater unity between her paintings and the surrounding room. Flora’s Cloak is framed in a stamped ‘Gluck Frame’, which was probably fitted during the 1930s. It was also in 1932 that Gluck, openly queer, met a new partner, the florist Constance Spry. They were introduced that January via an arrangement of flowers that had been delivered to Gluck that Gluck had decided to paint. Not only was a new relationship sparked, but Gluck also made a significant number of flower paintings that show how the artist’s sensibility aligned with Spry’s preference for well-spaced white floral arrangements that focused attention on the interplay between light, shade, colour and shape. During this time Spry came to own Flora’s Cloak, which hung above the fireplace in her Kent home, Park Gate, where Gluck frequently spent weekends. It is also said to have hung on the walls of Spry’s shop ‘Flower Decoration’, probably at 64 South Audley Street in Mayfair (which her business occupied from 1934 to 1960). Though the relationship ended in 1936, Gluck continued to paint floral arrangements into the early 1940s. Further reading Drawing & Design: Incorporating the Human Form, vol.4, series VI, November 1924, illustrated p.205.Diana Souhami, Gluck: Her Biography, London, 1998, pp.54-62, detail reproduced p.55.Amy de la Haye and Martin Pel, eds., Gluck: Art and Identity, New Haven and London, 2017, p.90, reproduced p.92.Rachel Rose SmithFebruary 2019

25/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Reginald Brill, Unemployed c.1934–6

Unemployed c.1934–6 is a large oil painting that depicts four men in shabby overcoats and hats walking in a line alongside a brick wall and pavement. The second of the men holds his cap in his hand as if about to ask for money and the man behind him appears to be chanting or singing, implying that they may be part of a larger group. The work is painted in a sombre palette of browns, greys and dark reds. The subject of the work is the Hunger Marches that took place in Britain in the 1930s and which Brill witnessed first-hand, an experience that deeply affected him. Although the Jarrow March of 1936 is the most famous of these, there were many others including the ‘National Unemployed March to London’ in 1932. Brill first started working on this subject matter in 1933 and showed another painting titled Unemployed in his exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in London in 1933.

26/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

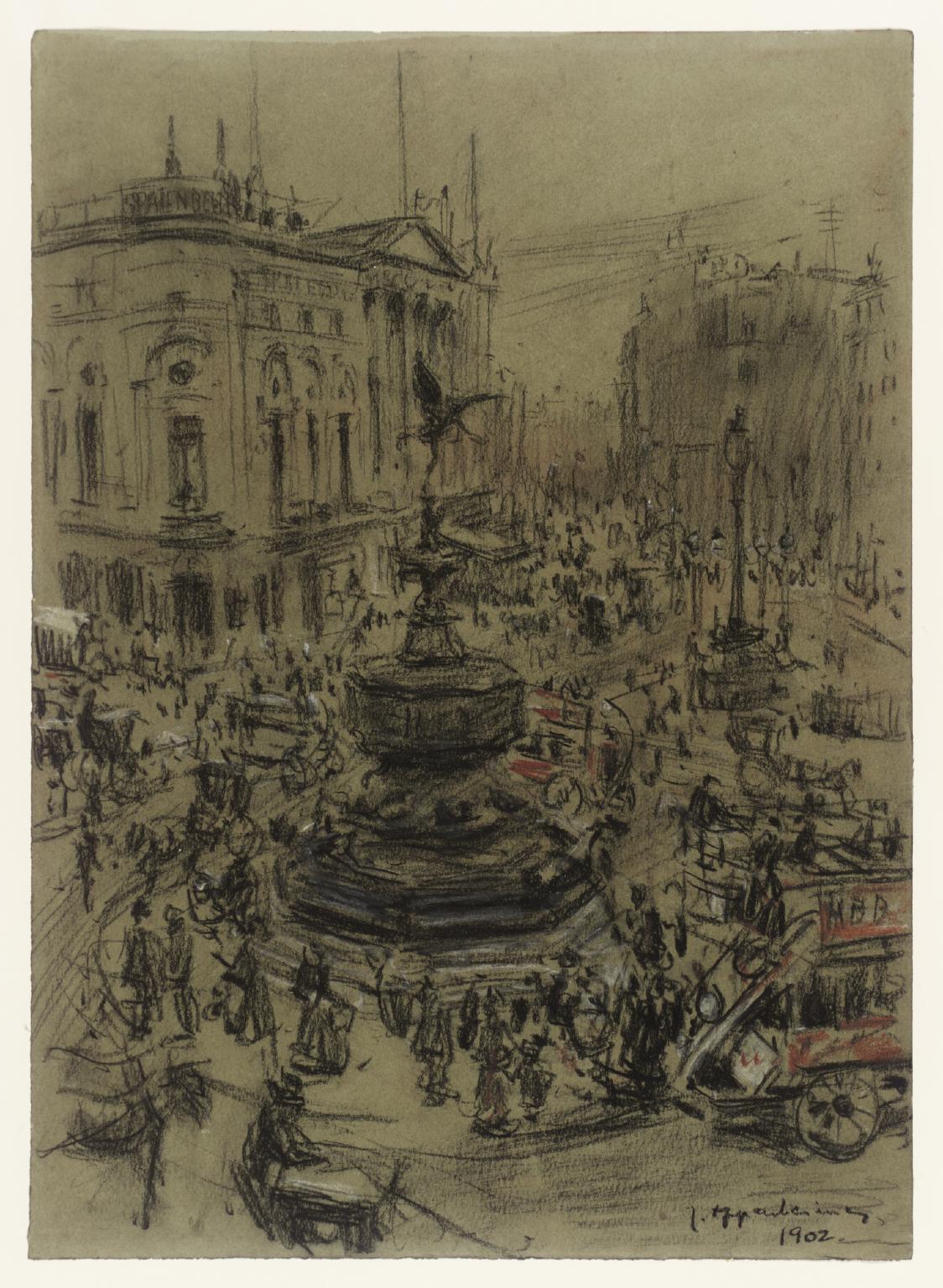

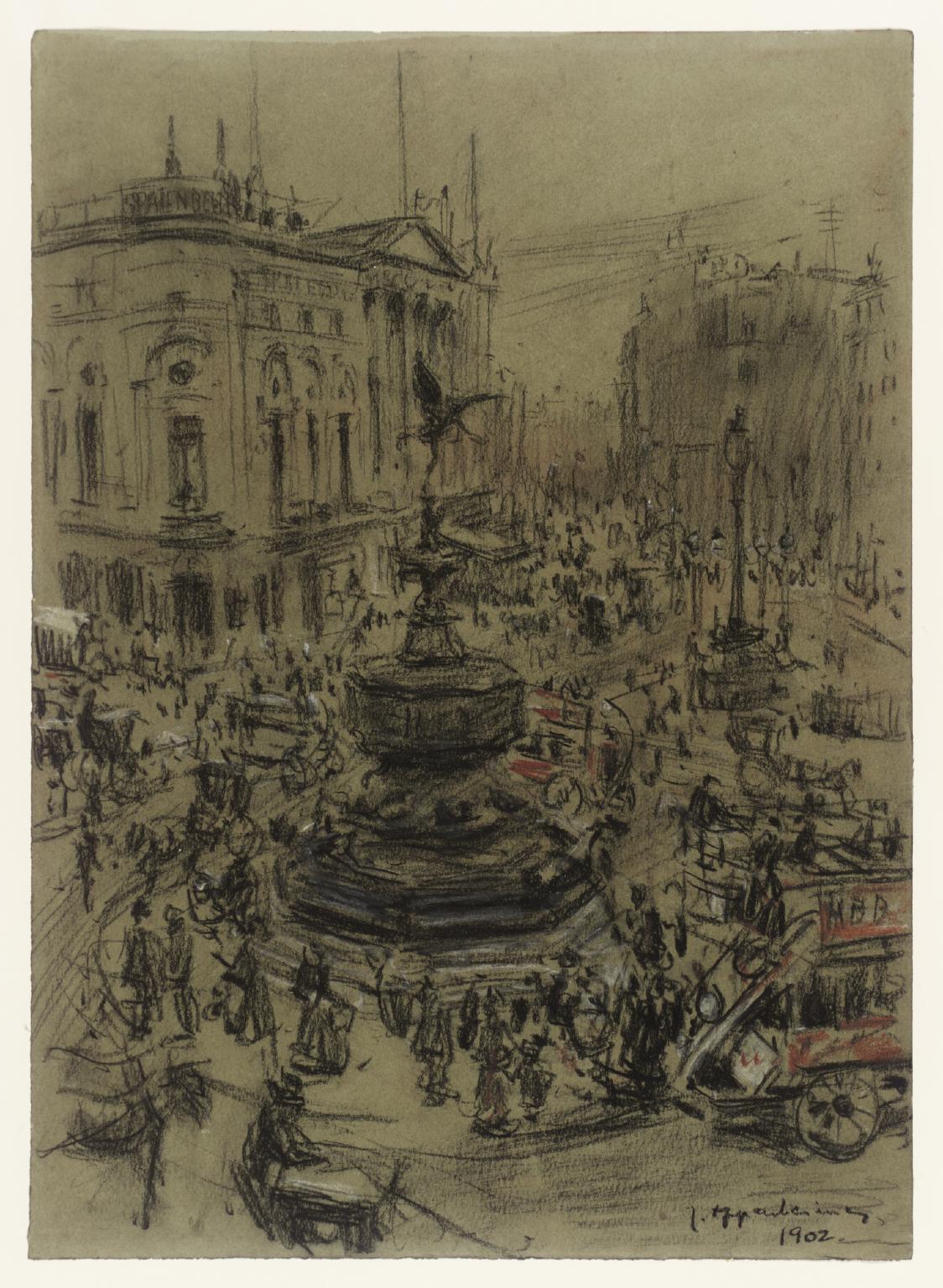

J. Oppenheimer, Piccadilly Circus 1902

This drawing shows the hustle and bustle surrounding the statue of Eros in Piccadilly Circus (a model for Eros can be seen in this room). Horse-drawn vehicles intersect with motorised buses and swarms of people crowd into the heart of the

West End.

The building on the left of the picture is the London Pavilion which was built in 1885 as a variety hall. In 1923, giant electric billboards were set up on the façade and in 1934 it was converted in to a cinema.

Gallery label, September 2004

27/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Clive Branson, Selling the ‘Daily Worker’ outside Projectile Engineering Works 1937

Selling the Daily Worker outside the Projectile and Engineering Works shows a man and a woman, probably the artists’ wife (Interview with the artist’s daughter, Rosa Branson, 5 November 2004.), selling copies of the communist newspaper, Daily Worker, outside a munitions factory in Battersea where Branson was then living. The message ‘For Unity’, promoted by both sellers on their aprons, presumably refers to the communist campaign for a united front against fascism. Branson became a member of the Communist Party in 1932 and remained an active member throughout his life. Harry Pollitt (1890-1960), the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain, described him: ‘Nothing was too much for him: selling the Daily Worker at Clapham Junction, house to house canvassing, selling literature, taking up social issues, and getting justice done – all those little things which go to make up the indestructible foundations of the movement’ (British Soldier in India: The Letters of Clive Branson, London 1944, unpaginated). In the centre of the picture is the red glow of the factory’s furnace, from which the workers seem to spew out onto the street. In the upper left, figures peer out from the window. The subject of a munitions factory in the pre-war years resonated widely, particularly within the communist constituency which saw the main victims of a future war as being working class people killed in the defence of capitalism.

28/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

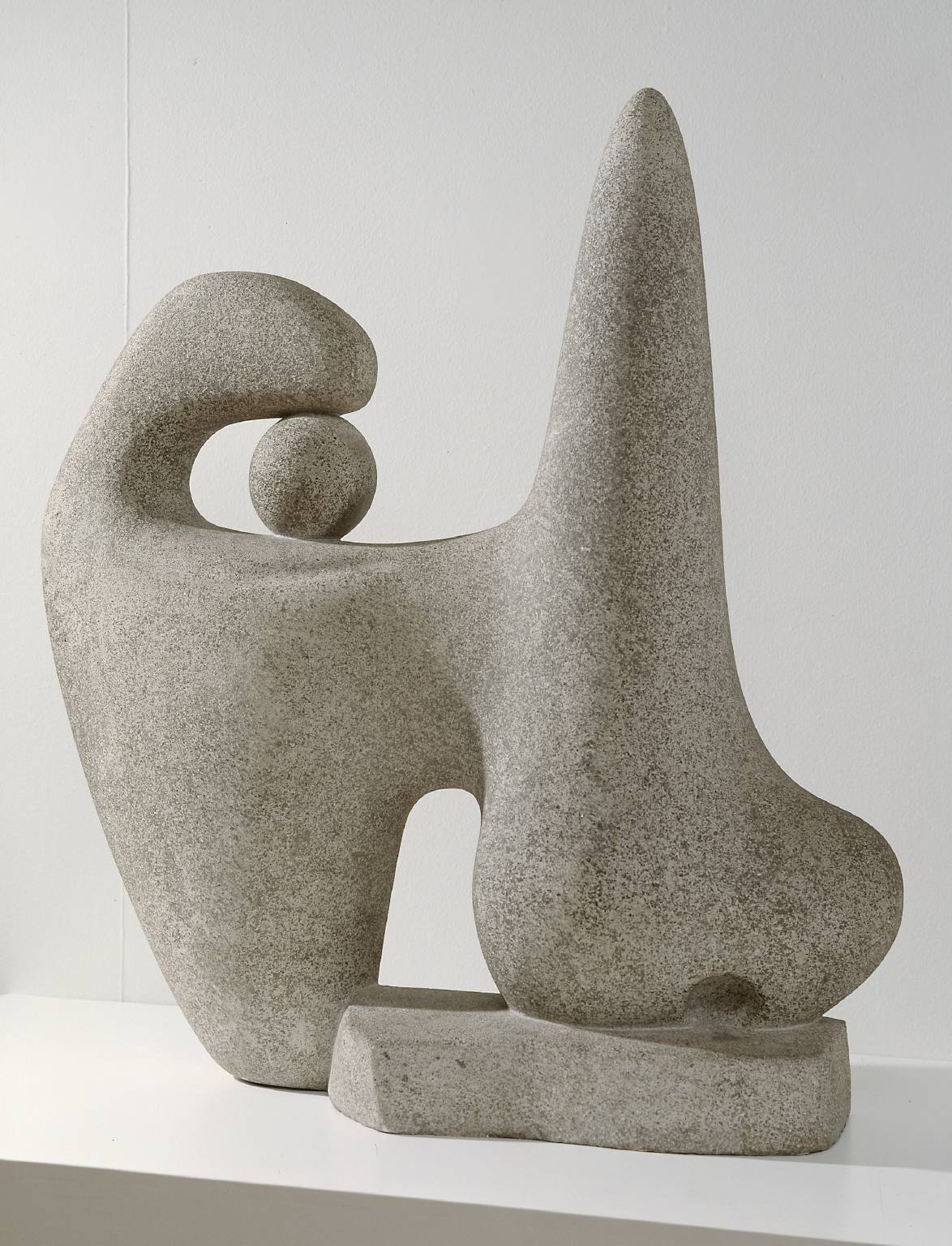

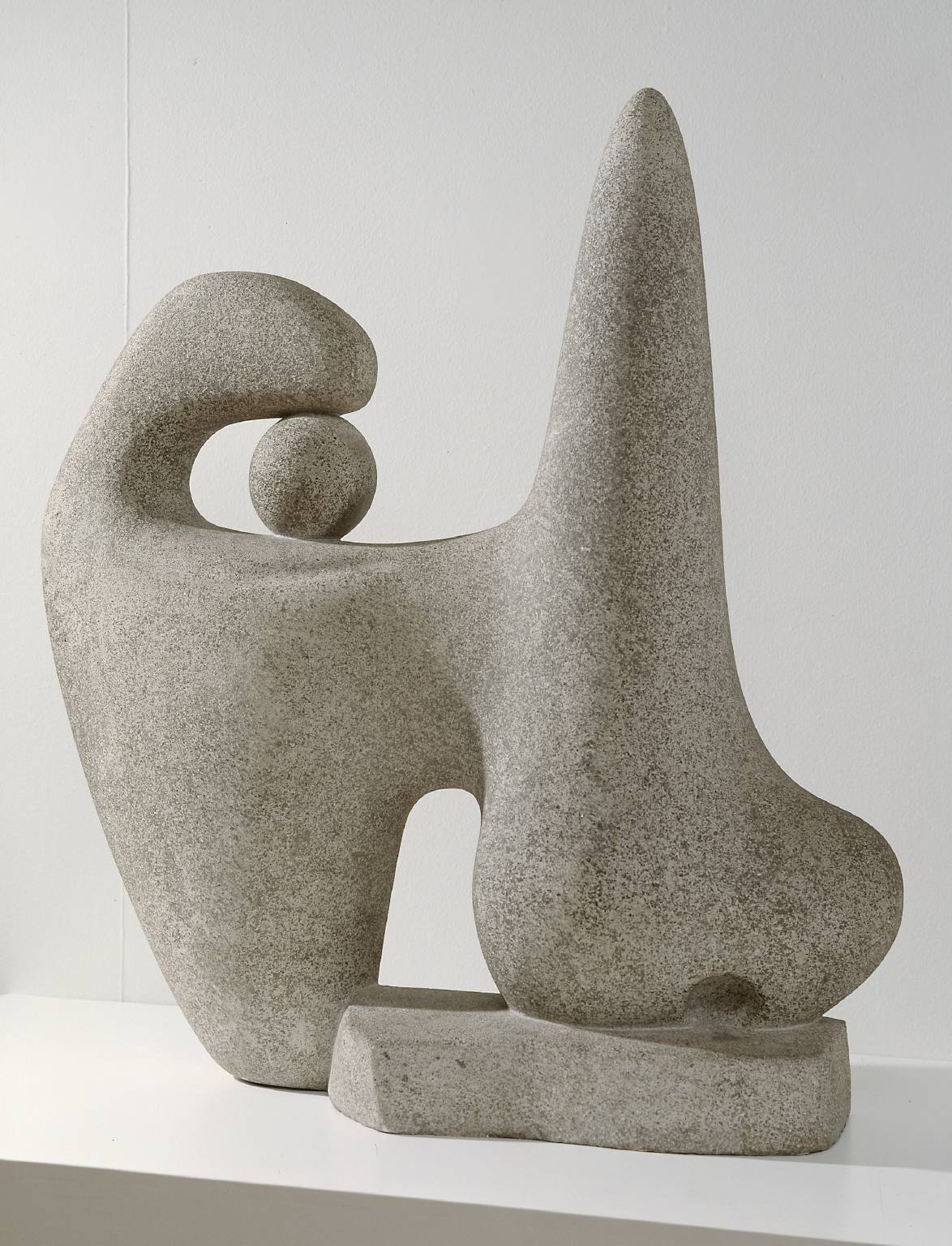

F.E. McWilliam, Eye, Nose and Cheek 1939

From 1931-33 McWilliam lived and worked in Paris. On his return to London he worked in an independent manner but was in close contact with the British artists Henry Moore, Paul Nash and Roland Penrose. The International Surrealist Exhibition of 1936 made a significant impact on him and, during 1939-40, he made a striking series of carvings in wood and stone which he entitled 'The Complete Fragment'. These carvings were mostly part or parts of the human head, greatly enlarged and complete in themselves. McWilliam was interested in the interplay between solid volume and surrounding space in these works, and also how the viewer completes the 'missing' parts of the sculpture in the mind's eye.

Gallery label, August 2004

29/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

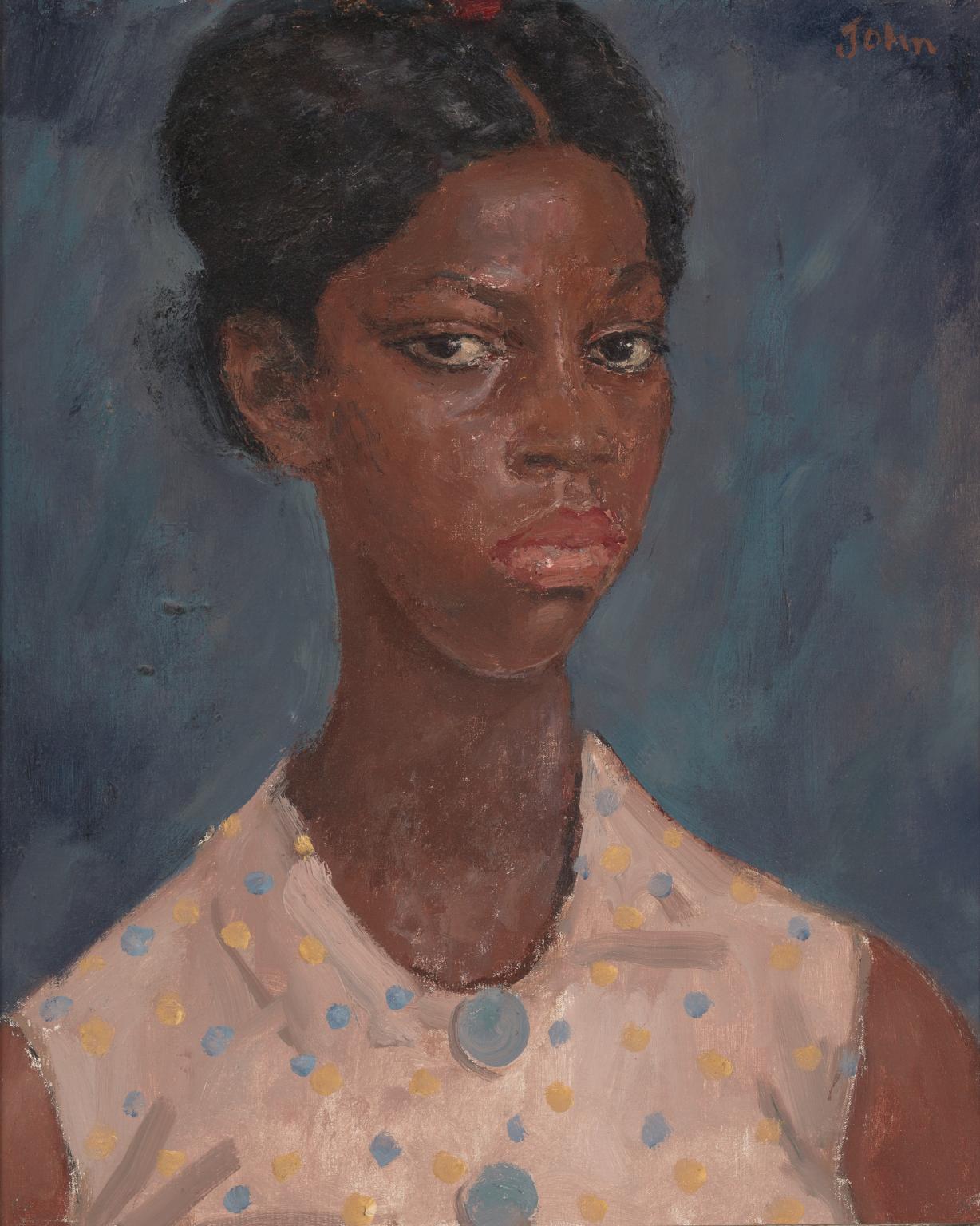

Augustus John OM, A Jamaican Girl 1937

30/30

artworks in Reality and Dreams

Art in this room

Sorry, no image available

You've viewed 6/30 artworks

You've viewed 30/30 artworks