Fig.1

Edward Hopper

Stairway at 48 rue de Lille, Paris 1906

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.1295 © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Edward Hopper arrived in Paris for the first time in October 1906, coincidentally a day after Cézanne died in the south of France. He remembered seeing some of the French master’s paintings at the autumn Salon that year, but took nothing from his painting, then or later, and it was partly as a result of keeping this distance that he used to be portrayed as an outsider from modernism.1 But in this stance Hopper is comparable to some British artists of his time, all of whom moved away independently from Impressionism along a different avenue from the one taken by the beneficiaries of Cézanne.

The possession of painterly skill may not be a necessary condition to becoming an outstanding painter in oils, but when it happens to be there, it certainly counts. Hopper’s natural talent for painting remains astonishing, and was evident early in his career, in the small sketch on panel that he made of the stairwell of the Baptist lodging house in the rue de Lille in Paris, where he lived for the eight months of his visit to France in 1906–7 (fig.1).2 It seems an unassuming little painting at first glance, but as a technical exercise in the control of colour tones and the depiction of space it is ambitious, and a tour de force. Not only does the realisation work, it also shows the overall joined-up modulation of paint that is characteristic of the French tradition. The unusually powerful character of his paint application can best be described as Hopper was no doubt born with what became this skill, but in the light of his prolonged studentship in New York this quality is most likely to have come also from the study of the paintings of Thomas Eakins, a concern encouraged in him by his teacher Robert Henri, who had studied with a pupil of Eakins. This predilection for rich paint may also have been reinforced in Paris by his sight of paintings by Courbet. It is not known for sure whether the Stairway at 48 rue de Lille, Paris was just a rainy-day painting, or if its dark colouring indicates that it was made soon after his arrival in France, in quick response to artists such as Courbet. The chiaroscuro of the stairwell, complex in this confined space seen from a bedroom doorway, makes up the perspective within the body of the paint itself, not just with its colour or its drawing. Hopper sought to catch the reflection from the stair treads, not totally successfully as yet, but the space is nevertheless forcefully convincing, and indicates the seriousness of his technical ambitions, here used in relation to a complicated architectural space.

When he first went to Paris, Hopper at the age of twenty-four was already a fully trained artist, and he did not attend any teaching studio there. He evidently studied pictures in the public collections, and painted a quantity of oil sketches as exercises, often out of doors. He looked particularly at how to heighten the colour of his palette while retaining the bulk of his paint, which was necessary to its ability to represent. He had begun as a painter of buildings, and he seized on the riverside life in Paris, reminiscent of his upbringing in Nyack on the Hudson but now on the smaller scale of the Seine. He set himself exercises in perspective and distance, painting flights of steps on the quayside, obscured buildings, views often looking down from above, and simple panoramas. He sought to paint the colour of the light reflected from buildings near the river. The Hopper scholar Gail Levin has suggested that he benefited from seeing an exhibition of paintings by Albert Marquet, and some of his colours echo Marquet’s acidic lightness and fluid touch.3 These sketches imply that he also looked at an earlier period of art, and had studied most carefully the direct landscape painting of the French tradition that had led to the heroic early period of Impressionism, when these artists seemed to possess the lucky talent of painting landscape directly, finding both space and distance in an original balance of light and dark. Hopper went back, extraordinarily, to the origins of Impressionism, and carried on from there, taking little notice of the more mannered or distorted subsequent styles of painting. He commented on this link while talking to Katharine Kuh in about 1961 about the light in his landscapes, reportedly saying of his Paris sketches: ‘They are in a high key, somewhat like impressionism or a modified impressionism. I think I’m still an impressionist.’ He qualified this by adding that these sketches were direct, about the ‘immediate impression’, while being very much concerned to represent with representing depth.4

This campaign of painting in Paris was a ‘modified impressionism’ in a way that maintained the illusionism of Eakins, where each touch of paint has its honest representational value as well as fitting the colour harmony and perspective. Hopper was quite aware that he had side-stepped around Cézanne, and said years later that while in Paris in 1906-7 he had thought the paintings by Cézanne at the Salon ‘lacked substance’, and had ‘a papery quality’.5 Both these judgments are strange ways of describing Cézanne’s paintings, but are extremely revealing of an artist distancing himself from a tradition by emphasising in contrast his own use of heavily applied paint. The idea that Cézanne’s painting ‘lacked substance’ is hardly understandable without some parti pris about the richness of paint, because that might be thought to be precisely what Cézanne’s paintings did indeed possess.

Hopper’s studies are what painting in general might have become if Cézanne had not existed, or had not been noticed. Cézanne’s lonely pursuit was eccentric, and Picasso’s response to his late Bathers in the winter of 1906–7 was a decisive and unexpected shift. But there remained a cluster of advanced artists who were launched just before this revolution. What might be called this ‘Pre-Cézanne Brotherhood’ of ‘pre-modern artists’, international but unrecognised as such and unknown to each other, achieved in their life’s work a new symbolism of colour.6 The artists pursued their careers independently, especially in the case of the very limited contacts between America and Britain. But Hopper and some British painters made different versions of the same thing, and a criticism of one artist can clarify the nature of the choices made by another.

In Paris, the latest descendants of the Impressionists clustered around the commercial gallery Bernheim Jeune, fostered by the director there from November 1906 of newer art, Félix Fénéon (1861–1944).7 It was through showing at Bernheim’s that the Nabis painters Bonnard and Vuillard were associated then with Seurat (who had originally been discovered by Fénéon), who was a key to the reputation of this new branch of the gallery. Bonnard thus appeared to fit in as a development of the luminism of the neo-impressionists, along with Auguste Chabaud (and even later on with the Americans Morgan Russell and Stanton Macdonald-Wright, who showed there in 1913). Hopper however visited Paris for the last time in 1910 and had no part in this programme and had no market in Paris, although the barely remembered Chabaud used an unusual orange-pink that was a later characteristic of Hopper’s palette.

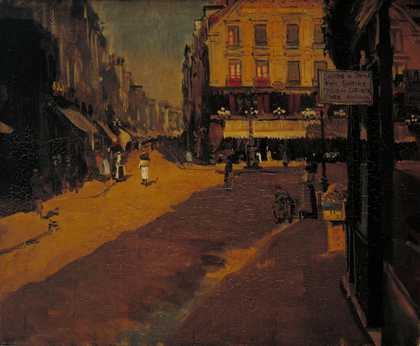

Walter Richard Sickert

Sickert (1860–1942) showed at Bernheim Jeune three times, in 1904, 1907 and 1909, always with a numerically very large display of paintings and drawings. His exhibition of January 1907 took place while Hopper was in Paris, and included such sensationally liberal nudes as La Maigre Adeline and La Hollandaise.8 Hopper was again in Paris when Sickert staged another exhibition at Bernheim Jeune, followed by an auction, in June 1909. This too included sexually frank nudes, including L’Affaire de Camden Town, which was bought by Signac.9 It is difficult not to think that Hopper’s only nude from that time, the Summer Interior painted on his return to New York, was encouraged by a sight of these paintings by Sickert, although there is no other evidence that he saw the exhibition.10 This was outstandingly not only Hopper’s most advanced picture, it also became a stepping-stone ten years later to the breakthrough into his long delayed mature style. Alone amongst his paintings of the time Summer Interior, 1909 implies real sex, with the model sitting on a bedsheet fallen onto the floor, undressed and casually posed, her pubic hair not hidden by some modest overlap of limbs. Unlike, however, with most of Sickert’s scenes, the other protagonist is not a man, but a patch of falling sunlight. But this Hopper was unique, and Sickert was a senior artist, almost twenty years the older and a master of a previous generation akin to Robert Henri. The coincidence at the time was more usually in the manner of painting, and in Sickert’s evident admiration for Degas, which was shared by Hopper. Sickert also had a touch of social issues about his subjects that was in itself unappealing to the affectedly dispassionate Hopper. It is typical of this moment of a lost style that Sickert’s 1909 exhibition has had little reputation since, despite its immediate reception as advanced, at a time when Sickert was regarded as, and might have remained, a French artist.11

Sickert was also keen on the continuity from Impressionism. He pleaded eloquently in the London press a few years later that Impressionism was not at all ‘played out’, nor should be replaced by some different manner of painting, especially not something deliberately controversial and intending to be admired (and hung in the Tate Gallery, he wrote) only at a future time. The trigger for this article in The New Age was probably the reputation of Matisse, following his retrospective exhibition at Bernheim Jeune in February 1910.12 Sickert argued instead for continuity: ‘A generation is arising here that has learnt its lesson from the Impressionists’. This was in London, but might just as well have included the young Hopper in America. This was the moment just before the widespread acceptance of the concept that styles of modern art should follow each other in quick succession – a conceptual change which explains the bite of Roger Fry’s exhibition title of November 1910 Post-Impressionism, an exhibition which notably excluded the Nabis.

There was a community of interest with these early Hoppers from across a swathe of English and Scottish painting before 1910, all part of a style that lacks impact because it does not have a name, although it was the opposing face to the successful Edwardian painting of the type that flourished at the Franco-British White City exhibition in London of 1908. These young artists were realists of a kind, and committed to finding the imaginative part of their art in their treatment of the painting, while conserving their direct, modern and homely subjects. The comparison across the Atlantic brings out some general contrasts. Among British artists there was a tendency towards portraiture, in contrast to Hopper’s typically American tendency towards narrative, with artists in the one case seeking more emphasis in individual character, and in the other on the local situation. Also, the kind of Impressionism that interested the British painters was to start with more that of Whistler than of Monet, with emphasis on overall atmosphere rather than on sparkling colours.

Gwen John

A developing interest in using touches of brighter colour in simple views is found both in Hopper and in some British artists working in Paris at the same time. Hopper’s first move towards modern landscape painting was the experiment of placing touches of brighter colour into a tonal view. In the tiny sketch on wood River and Buildings of 1906–7 he found an excuse for placing patches of blue and red in the middle ground.13 This is not, despite its size, a slight work, as it presages the beauty of Hopper’s handling of clear colours in his landscapes up to the 1920s. Gwen John’s paintings during her first years in Paris were few, and invariably of interiors, but she also sought a virtue in brilliant touches of paint on a very small, almost Netherlandish, scale. Her well known A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris (with Open Window), 1907–9 brought everything to bear on a distant patch of red on the wall of the house opposite.14 The comparison to Hopper’s sketches suggests that it was her skilful application of paint throughout this picture that was its great merit, rather than the interpretation of her self-image through pictorial autobiography.

This beautiful handling of paint was taken up and revised by Gwen John (1876–1939) in her most original work, the new style that she began in about 1915 with the series which includes the Girl in a Blue Dress,1914–5.15 This painting is made up of very evident separate dabs of paint. It is all ‘touch’, and plays with the de-naturing of the concept of an individual portrait through the insistent merging of figure and ground. When Hopper began his long delayed break-out from experimentation as an easel painter (he had worked as an illustrator) in about 1917, he reviewed first both his subject and technique through the procedures of making etchings. In this he was encouraged by a renewed look at Paris, in terms of the light and shade in Meryon’s etchings of the city. Hopper’s prints were still on the edge of being illustrations, but in his etching The Open Window,1915–18, the coloured brushwork typical of his preceding oil landscapes has been disciplined into a contrast of light and shade in etched line that here rhymes the figure with the setting.16 The figure and ground are barely separated by their different strength of chiaroscuro. Both Gwen John and Hopper by 1920 had stretched their view of Impressionism to become a realisation of image that was based on an emotional link between the anonymous figures and the overall density of the grain of the material that made the illusion. This was a fundamental shift, and opened new possibilities in painting through taking advantage of the property of painting and drawing to obscure as much as to reveal. However, the implied sexuality of these images in these two artists is very different, as was each of their future developments, but at this point of a new beginning they both coincidentally looked at a new motivation for their existing skill with touch.

William Nicholson

An art based on ‘touch’ may have appeared in 1905–6 to be of limited potential, especially in subject, but nevertheless it was taken up by William Nicholson (1872–1949), and eventually deployed by him as a vehicle of emotional depth. On returning to painting after an early career as a graphic artist, he looked first to Sickert as master, then after a spell in Paris in 1905 to a new Impressionism. His finished paintings retained the character of oil sketches, and were small and summary. The Brig and many similar pictures by Nicholson look as if they might have been made by a Hopper in Paris who had decided to complete a painting begun as an exercise by carrying on in the same way.17 Nicholson’s direct landscapes can be compared to many of Hopper’s, although the latter’s are usually larger, and present scenes in themselves more notable. But in both cases the colouring is broad, surprisingly sharp in tint, and the view unexpected in foreshortening. Nicholson’s Frost Whiteways is teasingly both minimal in feature yet aggressively spatial, and both eloquent in colour and yet barely brushed.18 Several rather later landscapes by Hopper similarly make much of low light to give clarity and eeriness, and to simplify features into a stark solidity. These comparisons suggest a way of looking at these paintings, keeping one artist in to mind slightly re-adjust our perception of an overlooked feature of the other. If this Nicholson landscape is compared to a mature Hopper landscape such as Hills, South Truro, 1930, the slightly unexpected minimalism of Hopper, familiar in Nicholson, becomes more evident, as does the Hopper-like concentration on lighting, the lack of figures and the clarity of Nicholson’s landscape.19 For both artists, their ordered realism and panache with paint can be seen as an extreme development of the direct painting of early Impressionism. Just as they had avoided modern styles, they slunk away from contemporary subjects. The range of their arts was different, but these were artists of a kind, difficult to place in historical style because of their emergence in the critical years of 1905–6.

Spencer Gore and Robert Bevan

Fig.2

Edward Hopper

American Village 1912

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.1185 © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Hopper’s first attempt at a personal style was, however, pointedly modern in subject, but was aborted, whether through lack of patrons, critical notice or his own restlessness, and it remained a unique episode of its own. His landscapes and town views of America of around 1912–16 were determinedly advanced in technique and up to date in subject, being often of urban transport. This was a great lost moment for modern American art, a group of experimental paintings that took the city at full face, finding more everyday and less dramatic views than appealed to his contemporary George Bellows. American Village, 1912, Corner Saloon, 1913 and Yonkers, 1916 were modern realist paintings without either social pleading or obsessive localism, and in themselves were a rival to the more overtly socialist work of the Ashcan artists (fig.2).20 Nothing is like them, and the comparison to the London painters of the Camden Town Group, who seem to have an identical motivation, in fact emphasises their difference. Letchworth Station, Hertfordshire, 1912, by Spencer Gore (1878–1914) lacks the bulk of paint and saturated colour of the Eakins tradition of Hopper, and looks as a result brittle and small scale (fig.3).21 The overtly modern subject is left in limbo, uncertainly placed between acceptance and disapproval, and while Gore’s paint-box colouring is attractive in itself, it takes away from the picture’s realism. Robert Bevan’s Hay Carts, Cumberland Market, c.1915, is richer in paint, but contradictorily uses a modern style to preserve a memory, the lingering presence in the city of the by then outdated horse transport.22

Fig.3

Spencer Gore

Letchworth Station, Hertfordshire 1912

National Railway Museum, York © NRM / Science & Society Picture Library

This painting by Bevan (1865–1925) may be compared to Hopper’s American Village, 1912. Beyond the suggestion here that America was a good deal more up to date in 1912, though less sunny, than Britain was in about 1915 (on this token evidence), there is an essential difference in technique between Hopper’s bound colouring and Bevan’s patterned mosaic. Bevan imposes a geometry, helped by the rectilinear bales of hay, and imposes colour contrasts, so that it is difficult to believe that just one of the tarpaulins that cover the hay happened to be coloured a bright sky blue. Hopper also soups-up his colouring, but only to a certain degree, retaining from earlier on his deployment of touch in the strangely red chimneys that are dabbed in about the scene. But Hopper is able to shade his colours, and so to include a greater amount of what happened to be there, unlike Bevan who had to find colour-box contrasts in the window-blinds opposite him. Bevan is stylish, where Hopper is inclusive, and can cope with a panorama to a good distance. The strangeness of Hopper’s colouring makes his view unique to his sight, and original, yet it seems continuous with the viewer, and we are glad to be kept secure from falling behind the parapet of a bridge in the foreground.

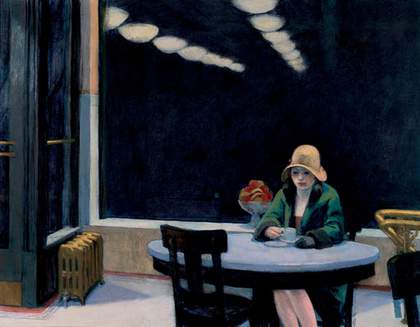

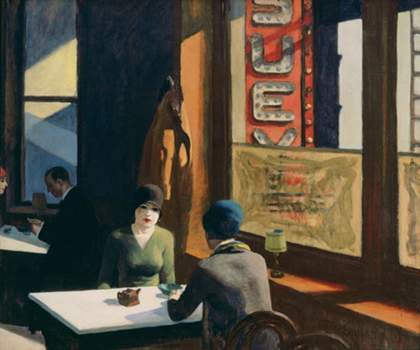

Fig.4

Edward Hopper

Chop Suey 1929

Collection of Mr and Mrs Barney A. Ebsworth © Bridgeman Art Library

John Duncan Fergusson

Hopper made an extraordinary one-off experiment in 1914, in trying out a large painting as a Symbolist allegory set in a Paris café, a scene which he recalled in New York a few years after he had left the city forever, partly by looking back at his own drawings. In this picture three young men – one ordinary looking figure who is perhaps a writer or artist, along with a soldier and a clown, who are also perhaps standing in as three versions of the same character– drink at a table. They are circled by three peripheral types: the commanding presence of a prostitute, staring at them from slightly above, and at either edge, like book-ends, the figures of virtue and vice in the guises of a bourgeois couple at the right and a sinister lone male, perhaps a pimp, at the left. The message seems to present the dilemma of the exposed position of a single man who is not able to join in with usual society. The scale of the picture is that of an exhibition masterpiece, and this in itself takes the picture beyond such models as Robert Henri’s Café Terrace, painted in Paris in 1899. Hopper’s title for his painting, Soir Bleu, gives it the literary context of one of his favourite modern poets, Paul Verlaine.23 But the painting falls between genres, too topical to be an allegory, and not real enough to be topical.

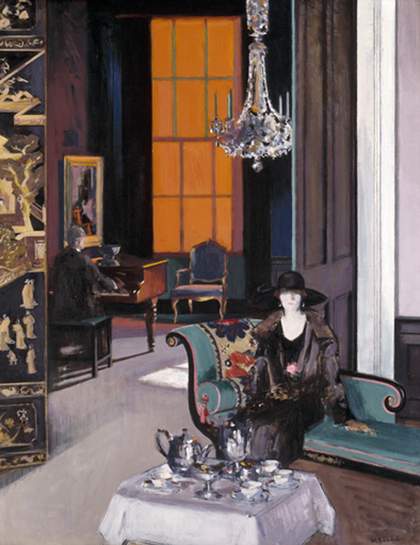

Fig.5

Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell

Interior: The Orange Blind c.1927

Glasgow Museums, Art Gallery and Museum, Kelvingrove. Hamilton Bequest 1928 © The Cadell Estate

It may have been impossible to re-create from so far away the look of a café in Paris that could serve as the vehicle for such a grand theme. The similar café in La Terrasse, Café d’Harcourt, c.1908–9, painted by Fergusson (1874–1961) when Hopper was visiting Paris, was almost anecdotal like Robert Henri’s café, and it remains convincing as a view of a place.24 But the attention given to the dominating full-length figure, and her stare at the viewer, makes this picture at the least a personal challenge to take up her offer of partnership. Hopper and the Scottish painter Fergusson were of the same world in Paris, and it is possible they had friends in common there, the sculptor Jo Davidson, who was modelling a portrait of Fergusson at the time of his café painting, and the American painter Anne Estelle Rice, Fergusson’s partner. Hopper’s figures rarely look at the viewer, who is usually in the place of someone who looks on without being seen. In Soir Bleu, his symbolism is old-fashioned in comparison to Fergusson’s, but Fergusson’s colouring, despite its brilliance, relies on pools of darkness to separate the figures. This gives a strange but powerful rhythmic movement to the modern Goddess standing at the centre, and gives syncopation to the crowd. While Hopper’s café clients barely even see each other, they and the whole scene are modelled in colour, and the five chair-backs, for example, in his picture are bound in to the overall colour range by their texture and by repetition of tone. Fergusson’s far more successful painting lead on to his annoyingly idiosyncratic heads and nudes that illustrated his personal female ideals, with their exaggerated busts. Hopper’s café scene was for his own immediate development a full stop, but both his confrontation with modern sexuality and the constructive manner of his painting had a far more positive long term future than did Fergusson’s more competent agility.

For pre-modern artists there remained a question about the subjects of their paintings. Since these were realistic, the pictures might become autobiographical or even confessional, following the artist’s own life and plunged into his or her own social world. But if that option were followed, then the artist could not disguise his status as reporter and observer, and not an equal sharer with his friends. A literary example gives a comparison. Tonio Kröger, the writer-hero and self-portrait of Thomas Mann’s short story published in 1903, suffers some of the anxieties of a pre-modern artist, and can be compared to Hopper. Kröger was unwilling to generalise or allegorise what he saw in the manner of an academic art, while at the same time he felt set apart from an ordinary life, and so unable to participate in the vernacular world that he wanted to write about. In this story Mann stepped back, in order to look at himself in the person of Kröger. Kröger’s problem was that he could not disguise himself, nor act as if sometimes a writer and sometimes not. An artist is ‘a man apart’, he says, ‘a man who does not belong, who feels that he is recognised and being watched’.25 He cannot escape from himself, and he suggests a hopeless charade:

Disguise yourself, put on civilian costume, dress up like an attaché or a guards lieutenant on leave – you will hardly have raised your eyes and uttered a word before everyone will know that you are not a human being but something strange, something alien, something different.26

This trio of personae is echoed in Hopper’s invention of his young man with two alter egos in Soir Bleu, where they are also exposed as something different, and stared at in a way that implies some impotence on their part. Mann’s story was about his personal life at that time when he was unmarried, but both Edward and Josephine Hopper, Edward especially, did through their lives take a stance that was somewhat to one side of mainstream sociability. But Kröger, invented for this story, was just the kind of character who became the hero of The Magic Mountain, his life in the sanatorium described from the outside. Similarly, the imagined viewer of the café in Soir Bleu became much later an essential invention of Hopper’s art, the voyeur who watches from his or her own space what goes on in city and suburban buildings.

Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell

Hopper’s painting in the 1920s was markedly individual in comparison to his contemporaries in New York, and he moved it further in two original ways, in terms of colour and of emotion. His colours are never broken, and he never painted in impasto in the manner of Van Gogh, but he was able to sharpen his colour values while retaining extremes of light and shade. In a later café interior Chop Suey, 1929, Hopper contrived to bring together a certain earthy quality of pure green, blue, mauve and orange with other evenly brushed colours, all at an intense saturated richness, while giving a strong effect of sunlight and shadow (fig.4).27 The colours so lack modulation that sections of the painting appear abstract if seen on their own. So much is drained out from the scene, and simplified in the application of detail as well as in the demeanour of the figures, that his choice of colours takes over as the lead interest. The orange colour is typical of Hopper, often used by him beside a similar green and brown. The touches of shrill colour in his early Paris sketches have now spread, to represent the more adventitious and artificially chosen features of this humdrum interior, where they stand for life amongst the architectural co-ordinates of the surroundings. But the colours still have the quality of bulk, and the colouring overall is bound together across the surface in the manner of French painting, as in Monet and Pissarro. The work of another Scottish painter, F.C.B. Cadell (1871–1935), who used at the same time a similar palette and was also devoted to experiment in colour, illustrates the difference in construction. His Interior: the Orange Blind, c.1927 (fig.5), shares with Chop Suey an interest in the colour of a modern interior, despite the very evidently different concerns with social class (between an Ainslie Place studio in Edinburgh, and a restaurant at Columbus Circle in New York).28 For Cadell, his attention was triggered by ownership, and there is a sense of an inventory about his displayed possessions that extends into the distinct colouring, and the areas of impasto that help to delineate and separate the shapes. The colour of the remarkable vertical blue line that marks the edge of the door is not repeated elsewhere in the picture. But Chop Suey in contrast is held together visually by near repeats, and has much less differentiation in the colours. There is not a single highlight or sharp edge, and some shapes – like the ladder pattern at the right, and the crossed beams at the left – are unexplained. Hopper’s colours have a formal value, of some independence beyond their narrative function.

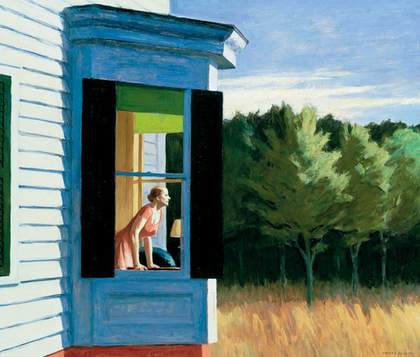

Classic Hopper

But there is a further role for colour in Hopper’s mature paintings, one of emotions, and in this he appears to have been unique, and beyond comparison to the other pre-modern painters. The orange of the street sign in Chop Suey is similar to a colour he had used earlier in Girl at a Sewing Machine, c.1921.29 There are two kinds of intrusion in that painting. The light falls with an invading force through the window onto the plump and partly undressed figure, as if in an old master painting Danae receives her shower of gold, now with Hopper as a metaphor for a physical love that takes the form of light. The observation of the viewer is additionally intrusive, as he or she sees something private, without being noticed by the subject. These senses of penetration, of the viewer and of the light, became essential to Hopper’s vision. He was proud of solving the pictorial problem of showing both inside and outside a building at the same time, by means of looking through the large window of a shop, office or restaurant, to reveal both the room and the building itself, a characteristic set-up that he often painted. There was always a subdued sexual implication in this attitude, which sometimes in his later work became overt. In High Noon, 1949, an overlarge and underdressed woman stands in an open doorway, for once rather too obviously a sign of sexual appetite.30 This figure punctuates, and makes more explicit, what is felt in strictly painterly terms about this odd doll’s house in bright sunlight, placed in a desert without even a front path to the door. The subject is so dislocated as to suggest a sinister feeling in the extreme black of the interior of the little house. High Noon makes clear that the fall of light is associated with a sensualised contact for Hopper, as if a metaphor for the power of observation that is fully alert, committed and sexually predatory. In this sense, the pattern of the window on the wall of the earlier Girl at a Sewing Machine is also a sensualised touch of light onto a texture. This contact is the more significant within his paintings as the figures themselves usually (though not always) avoid conversation, and the power of the penetrating sunlight acts undiverted.

There was a change in Hopper’s later paintings toward subjects that became less natural, while their concealed erotic content became more strongly implicit within the colouring itself. In a classic Hopper painting such as Room in New York, 1932, there is an overt breakdown of relation between the couple in this domestic marriage, which is made the more poignant (rather than potentially as trashy as a soap opera) by the brimming light from an unseen overhead lamp.31 The window has been artificially enlarged so it looks like a wall that has been removed, and there is an additional breakdown as the viewer stares at this intimate drama without being noticed, from a point close to the front of the building, like an audience in a theatre. If this picture had been painted like an illustration cut out from a comic book it would be of very little interest, and unable to hold its scale. But Hopper’s thick, rich paint acts through a new development of paint’s potential to seem like flesh that had been so exploited by the old masters. Within its absorbent texture, in areas of unmodulated colour, light is held present, to make active that sense of its ability to receive impregnation and of our own sharing of this through our intrusion. Such effects cannot be felt in reproductions of the painting. The scene is contemporary, of a couple at home in the evening, universal and unremarkable. Through his long practice of observation and creation Hopper found a means to represent the sensualisation of everyday life. This was a unique fetishisation of the appearance of life in modern settings, something that had eluded the Surrealists in Paris, just as it had also eluded a specialist in sexualised modern interiors such as Stanley Spencer in Britain, whose Workmen in the House, 1935, relied on a fairly obvious suggestiveness of shapes to express a sexual charge.32

That odd painting Soir Bleu posed a problem about the distance of the artist from the subject, as to whether he (or she) could be a participant in the life that he was studying. The answer was evidently negative, and the only corner of the picture that had a direct future for Hopper was the painting of the unexciting married couple at the right, who might have re-appeared in a later painting, after Hopper had returned to figures. The fictional Tonio Kröger fled from his modern painter friend in Munich, to go back to the North, where he came from, and see again his favourite landscape – the sea, as it happens – and there to stumble across by chance the type of people who had once been the subject of his infatuations. But now he has the answer: these people that he might have loved must remain his subject, but he can only look at them from inside a doorway, in the shadow, and never participate. His characteristic stance while making observations for his writing was to be, like Hopper’s, ‘watching the dancers in the lighted room’.33

Hopper’s sensualised shapes and surfaces gave rise to a new kind of fictive architecture. At the close of his career he was able to increase the size of his pictures, as his buildings and interiors in themselves became more eloquent. These pictures are certainly not abstract, but it is not surprising that they were admired by post-war American abstract artists, some of whom were also dealing with planes of not quite flat colour that were loaded with a sense of life. This was not a relation of influence, but nevertheless marks a continuity with a certain idea about the role of colour. Most of the British artists mentioned above – the Scottish colourists, the Camden Town Group and William Nicholson – were in contrast the end of a line, summing up an existing experience of painting, and not becoming an example to later generations. There were two exceptions: Sickert, who constantly revived not just his manner of painting but even his own personal character; and Gwen John, who was a special case since her paintings of around 1920 only became known when they were exhibited in London in 1946. Both she and Sickert were admired by a younger generation, and had a debated but real effect on the artists of the School of London. All these artists, and Hopper, have been regarded as difficult to place, but their position is better seen as one carrying forward a long tradition of painting in France, while standing to one side of modernism.